I’m in Murrieta, California, ground zero in the immigration debate.

I’m watching hundreds of protestors and supporters at a hastily called town hall meeting at the local high school.

Police surround the auditorium to shield between protestors and supporters. A massive wall of news vans fill the parking lot. Reporters with news cameras troll the crowd hunting for sound bites.

On both sides, people fly American flags. The crowd is polarized with protestors and supporters—islands of different groups arguing. The borders are blurred between the groups.

Many hold signs with specific messages. The crowd outside is mixed, from locals to out-of-towners like myself. Inside the building, the local politicos ask questions about the plan to relocate busloads of women and children through Murrieta.

There are hundreds inside and it’s overflowing and overcrowded. A loudspeaker keeps the outside overflow informed. I hear the meeting inside and the arguments between these groups outside. I stand in the middle. The town folk and city officials are feeling overwhelmed and under siege. What will they do with these children? Many are unaccompanied to our borders, many Central Americans that are now streaming over our borders hoping for a new and better life in the United States. And the citizens of Murrieta are scared.

It’s a humanitarian crisis but standing outside in this crowd, I see it more of a confidence crisis—a lack of confidence that I have never seen before. I notice a palpable feeling of fear here in this quiet little conservative community. Fear brings out the best and worst in all of us, and that’s what I’m seeing here in Murrieta. There is fear that they are losing America. Some say it’s not a humanitarian crisis, it’s an identity crisis.

Everyone is trying to find a side on this border issue. Some see me taking pictures with my cell phone and ask me pointedly, “Where do you stand?”

Where do I stand?

It’s a complex question—one that even Congress and the president can’t solve. It’s a complex problem and the media loves easy sound bites.

I see a news crew rush to an argument between an Anglo man with his teenage daughter by his side holding a large American flag. The flag is wound up tight and wrapped up around the pole. It looks more like a spear.

He’s tense. He’s arguing with a Mexican American vet I met earlier, “I’m not a racist. I love Latinos, but this is too much. We can’t take care of the whole world.”

The Mexican American debates him heatedly. It’s looking racial more and more.

“These are just children,” the Mexican American yells. “What if they were your sons or daughters crossing over to look for help?”

The Anglo man angrily responds, “Well, I would never have let my kids come over here without me. Why would these parents over there do that? Don’t they know how dangerous it is?”

The Mexican American man clarifies, “ Their parents ARE here.”

I thought to myself that this has happened before. Jewish parents during World War II were desperate enough to send their children to America by boat to flee the Nazis knowing they might never see their children again.

I remember the Cuban Pedro Pan program that sent children to the U.S. without their parents—unaccompanied minors fleeing Castro.

Desperation fuels desperate measures. The news crew filming this exchange has enough anger so they turn off their lights and cameras and look for more embers of hate in this immigrant firestorm. I stay with this debate after they leave.

In the same argument, the Mexican American man says to the Anglo American man, “Hey, you should unroll your flag.”

The Anglo man looks confused.

I understand what’s going on so I step into this debate and tell the Anglo man, “Sir, he’s a vet and he wants you to unroll your flag.”

I see the respect in this vet’s eye for that flag. I recognized that patriotism, from my overseas experience entertaining the troops on the island of Diego Garcia.

“He wants you to display the flag. He’s a vet. The flag should be flown and displayed unrolled.”

The Anglo man begins to understand and softens as he comes to realize the other man is a vet. too.

“Oh yes, I’m sorry,” he apologizes. “I rolled the flag up because my daughter and I were going home.”

He unrolls the flag and waves it. The other man says, “You should wave the flag proudly – I would.”

The Anglo man then reaches out and shakes his hand. He recognizes a fellow vet. They’re no longer enemies on the other side of a debate—they are just two Americans looking for answers. I see a glimmer of hope. And there is not a single news camera to capture that moment.

I see another sign. It’s a picture of a Native American with a ceremonial feathered headdress that reads “THE REAL AMERICANS.” Another sign reads “JUSTICE FOR OUR KIDS.”

A group of Latinos turn to me and ask me where I stand.

“Are you on our side?”

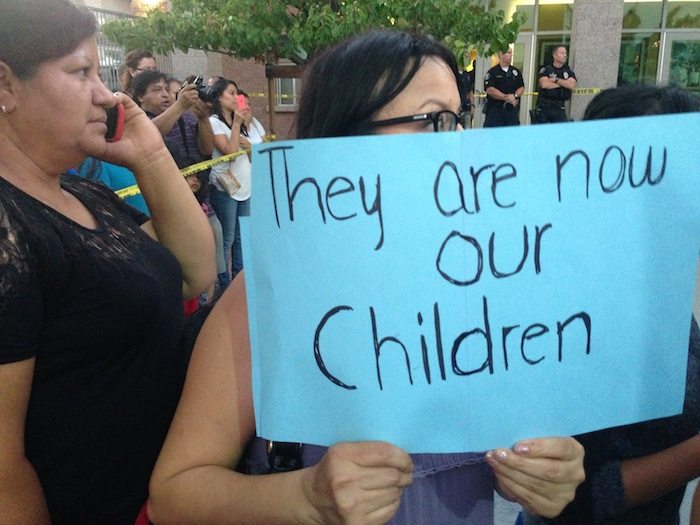

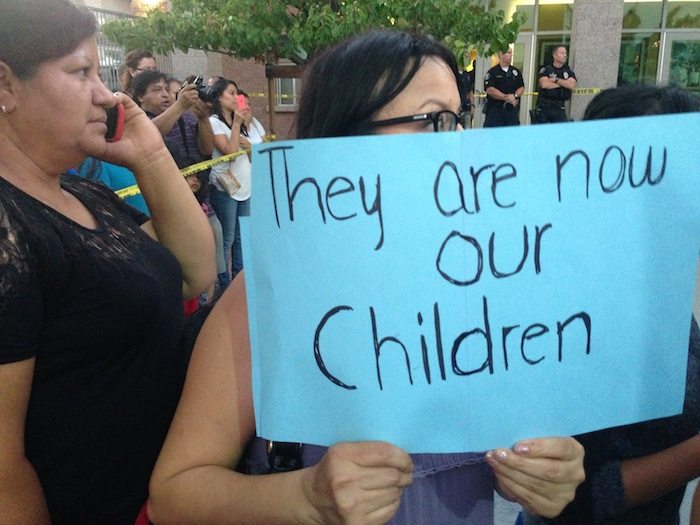

A woman holds a sign behind me that reads boldly: “THEY ARE NOW OUR CHILDREN.”

This is the debate aside from politicians and federal officials and terrified soccer moms. One local soccer mom interrupts and tells me, “I give money to children overseas. I’m a good person. I give money to charities overseas to help them.”

She has a mixture of guilt and concern in her face. I tell her kindly feeling her fear, “Yes, but these children are here now and like the sign over my head, I have to agree they are now ours.”

They ask again what side I’m on. I think and answer, “I’m on the children’s side.”

In the town hall meeting going on, an unseen person speaks over the loudspeaker:

“These children are crossing our borders, many unaccompanied by adults. What will happen to these children? Many will stay – they are not going back and we will have to take care of them for generations,” he says.

“They will be a strain on our already overtaxed system,” says another.

“We can’t even take care of our homeless vets or give them medical attention,” one person says.

The town hall erupts with applause, forcing the crowd to almost choose between our vets and children. It’s a hard choice but I don’t think it has to be. I get angry and think to myself, “Don’t start a war if you can’t afford to pay for it.”

But that’s another debate.

I hear another person ask, “What if they bring diseases? Are these children being screened?”

An expert quickly responds, “Yes, they are examined for TB. Many children have smaller lungs and are less likely to spread the disease.”

I fixate on the image of little lungs trying to breath safe and free. I keep thinking to myself, they are our children. Maybe because I’m Latino I can see that easier. I think of my own children and how small they seem when I hold them in my arms.

One woman leans over and says to me, “I’m from here, we are not hate-filled bigots. There are some, but I love people. Many of us locals asked to help these kids. I don’t want those children on that bus to think all of us hate them, that’s only a tiny few. They’re just louder.”

One local activist, a young Latino, calmly asks when he gets to the microphone, “Sir, there has been an immigration reform on the table and our lack of action in Congress is the reason we have these problems. What can we do to fix the system?”

He’s intelligent, sincere and looking to solve this problem. He wants to be what I truly believe, that Latinos are the solution, not the problem.

Then a besieged, tired official thanks him and says, “The real problem is Washington. All those congressmen with a letter after their names, letters like “R” for republican and “D” for democrat. The problem is in Washington.”

I think to myself, in the midst of this crowd, it seems the problem when it comes to immigration is that it’s always somewhere else. Even the solutions are somewhere else to be found. But now the problem is here and it’s in Murrieta, California and it cannot be ignored and I look at that sign that reads “THEY ARE NOW OUR CHILDREN” and I’m reminded that those refugee children are not somewhere else—they are here.

And whether we like it or not, they are our children now, our children. We need children to remind us sometimes to be adults and to be an adult is to be brave, and mature and tackle those hard questions and find those answers. My own children have forced me to be an adult and grow up. Children teach us to be better than ourselves. Children teach us to look to the future. And these children are here and they need answers.

***

Great writing. The sympathetic and respective perspective for “both” sides is important to helping us see a different picture than either “side” might broadcast over the media. The scene of two vets at odds, then leaving as comrades is especially important to understand the fervor and concern of the locals. Thanks, Rick.

[…] By Rick Najera / Latino Rebels […]

[…] Fuente: LatinoRebels.com […]