I wrote the following essay hours before New York City and the rest of the world reacted to the Eric Garner case. Once again, the system dehumanized another person of color. It is of little consolation that the pictures of Garner doing the rounds show him in cap and gown. Will the next Black or Brown person confronted by the police, regardless of appearance, end like Garner? Not if we are divided. We must hold the police accountable and we must look for ways to change the system. With that said, I am very grateful that my editors agreed to publish the following piece. This is very personal for me.

There is a meme making the rounds in Facebook. Again.

It supposedly shows Michael Brown with a wad of money in his mouth, gun in his hand, a Hawaiian Punch and a vodka bottle. In the background, a second African American person seems to be smoking tobacco or marijuana. Since the original post this past August, the picture has gone viral.

As reported by The New York Daily News, “Marc Catron [A Kansas City, Mo., police officer] allegedly shared an image of an accused murderer that he thought was of slain teen Michael Brown, with the snarky caption, ‘I’m sure young Michael Brown is innocent and just misunderstood. I’m sure he is a pillar of the Ferguson community.’”

The image has been proven not to show Michael Brown. From the same Daily News story: “This photo is not actually of Michael Brown, but many people believed it was and shared it on social networks. Kansas City, Mo., police officer Marc Catron is under internal review after allegedly posting the image on Facebook.” But the damage was done. And it was done too easily.

Fast forward to Ernie Lemmons’ public Facebook page. Lemmons reposted the image on November 25, with the following caption, “You know who Michael Brown is? He’s the 18 year old, 6’3” 295 lb. man who robbed a convenience store in Ferguson, Missouri, got shot and killed by a cop, whereby demonstrations and riots have erupted ever since. Here’s a snapshot that came from his Facebook page…… Has anyone seen this on any of the news networks or in the news media?”

You will notice that it has been shared over 28,000 times.

There are a few things that I want to explore here. First, despite the image being proved wrong, much of the public wants to believe that it depicts Michael Brown and that his holding a gun and biting a wad of money somehow justifies his extrajudicial execution.

Secondly, I’m appalled by the reaction of so many Latinos, and specifically Puerto Ricans, as far as social media allows to see. It seems to me that too many people of color have been quick to accept that Michael Brown was a thug who had it coming. I lost count of how many people I have unfollowed or unfriended in social media (and in real life too) for reposting this picture and refusing to believe that it is not him.

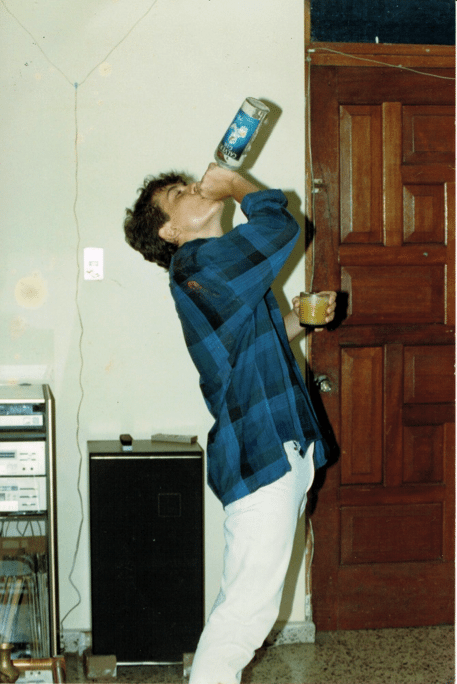

But unfriending people is not enough. At least it is not for me. This is a very personal issue for me for this very simple reason: I could’ve been Michael. There are photos of me like the one supposedly showing Michael, sans the gun. These photos were taken by my friends, at my request, in my teens and early twenties. In one of them, I appear to be drinking straight from a cheap gin bottle in the apartment of my best friend’s brother. If you look closely, you noticed that my hand is actually covering the bottle’s mouth, which has the cap on. It is a pose. Nothing, but a cool and fake story to get some street creed. That’s all there is to it.

In another, I’m posing shirtless with some seven thousand dollars in my hands, lighted cigarette in my mouth, as I do what by any account would be a gangsta pose. I guess I was doing what many people growing without any money would do—even if the money was not theirs. (It wasn’t, by the way. It belonged to my brother and two of his friends who had just sold their old boat.) So you see, pictures can be very deceiving. In those two pictures and countless others, I look like a troublemaker or, according to some, a thug—if we are to judge by comments in media.

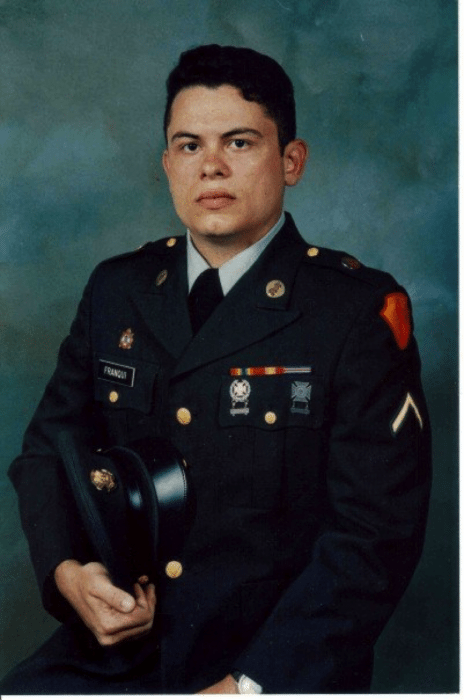

Should my character be judged by those pictures from my youth in which I’m trying to appear as “having made it?” With “money” and “power” that obviously I didn’t have? But here I am, many years later with a Ph.D., a career, a family man with a decade of military service, an upstanding citizen, so to speak. Who would think that I had been a “thug?”

The question is then, what saved me from being gunned down by the police or from spending my life in and out of jail?

One thing saved me.

White privilege.

I’m Puerto Rican. This may startle you. But, since I was born and raised in Puerto Rico, I enjoyed white privilege. My family, for all intents and purposes, socioeconomic and culturally, was a Caribbean mulatto one—though many of my siblings may disagree (we roll like that in the Caribbean).

The German name my parents gave me and our Corsican last name inherited from a landowner some in my family still call abuelo helped me claim white privilege. But it was my very light skin, freckles and copper hair (a trait from that abuelo I never met) that closed the deal. My relatives, neighbors, teachers and even the cops presumed me a good boy, smarter and more handsome than my relatives and peers, and destined to have a bright future because of my complexion, which made me white in el barrio.

I was not even 10 years old when I started to realize the privilege I enjoyed. At that age, I could tell that people were treated differently depending on their skin pigmentation—regardless of actual accomplishments (or lack thereof), or behavior.

On a busy Saturday afternoon, as I packed groceries at a Pitusa store on Calle Post Sur in my hometown of Mayagüez, two Afro-Puerto Rican senior women asked me my name.

“Harry,” I said.

They glowed.

“Oh my God, named after the president [referring to Truman who had been president 20 years ago] and so white!”

(She said this as she rubbed my arm, making sure I was truly “white.”)

“You are going places,” the other said.

And I smiled awkwardly, feeling both great that “I was going places” and wondering why my name and skin color were signs of a promising future.

You see, there is one thing about white privilege, and that is that you don’t have to understand it or recognize it to benefit from it because it is systemic. So mostly unbeknownst to me, I rode the wave of white privilege in Puerto Rico.

I even had an encounter with the police, well, many of my friends and I had an encounter with the police. One Halloween night when I was a teenager, my friends and I met with some other 40+ teenagers and we threw eggs, smoke, stench bombs and water balloons until the police came. Then we battled the police and soon we were outflanked, rounded up and sitting in patrol cars. I remember being in the back of a patrol car with my friend Alex, who lived in one of the projects (caseríos). He was probably the darkest person in the whole group. (He had dreadlocks! In the 80s! In Puerto Rico! What a transgression!)

The police patrol cars drove in different directions. Alex and I were taken to the Eugenio María de Hostos monument, devout champion of independence and known in the hemisphere as “Teacher of the Americas,” just a few miles from downtown. They grabbed Alex by his dreadlocks and pulled him out of the car. They asked him questions and did not wait for answers. They punched him and slapped him a few times. They told him to walk to his house, which was several miles away.

I waited inside the car. I was very scared.

If they did that to him when I was there as a witness what would they do to me?

Nothing.

They did nothing to me.

They opened the door and asked me to come out.

They looked at me briefly and one of them said, “He is one of the good guys.”

Another said, “Don’t hang out with those guys (esa gente), walk home.”

And that was it. I was relieved. But I was really ashamed for what had happened—not for battling the police with eggs and water balloons, but for the way my friend had been treated.

It was at that at moment when I truly realized the white privilege I enjoyed. Alex and I had done the same thing. If anything, I had been a little more wild and belligerent than him but there I was, scot-free, all because of my skin color and copper hair.

This is something that many Puerto Ricans —in Puerto Rico or here on the mainland— don’t ever get to realize, unless it touches them personally. I’m glad that I did at that moment, for it prepared me for when I joined the diaspora in 1999. Paradoxically, I felt free when I lost my white privilege on the mainland. I guess that in itself is a privilege.

That this fake Michael Brown picture is again doing the rounds and being reposted on Facebook by Puerto Ricans truly touches a nerve. For many Puerto Ricans in the island, Michael “had it coming.” They are predisposed to believe that because they don’t realize their own white privilege and when they head over to the mainland and become part of the disapora, many remain oblivious to structural racism. The fake picture confirms their suspicions and hides their racism.

When we as Puerto Ricans, as Latinos, as people of color, engage in this type of character assassination and don’t even give the benefit of the doubt to those who can no longer tell their story, we strengthen the structures that keep us down and we empower those who one day may gun down our own children.

Racism is real. Even with my education and in my position I experience it.

However, don’t worry about me. I’m very thick-skinned. I have the cultural capital and the tools to overcome racial discrimination, be it systemic or quotidian. But I do worry about the millions of people who will never have a chance against the system. I worry about the millions of Black and Brown kids who will be funneled from kindergarten to the juvenile centers and prisons, just because of their color and the stereotypes and stigma that our society associates with them.

I see it every week. Monday to Friday. I take the 6 train at Lexington and 68th and I travel to 125th before taking my final train into suburban life. As the 6 train heads north towards El Bronx, it gets darker and poorer. It gets multilingual, the stations get dirtier, the police presence heavier and their attitude more aggressive.

Not only does the train get darker and poorer, it also gets younger. Black and Brown mothers, and sometimes fathers, riding the train with one, two or three little kids. They remind me of my own children, happy, very happy and playing with their siblings, snuggling with mom, dad or an older sibling.

It just breaks my heart that in a few years many of those boys will become numbers and statistics for a system that funnels them from school to prison to pay for imagined transgressions. Or that their sisters will soon find that they live in a system that will abuse them and deny mobility but to a few of them.

At that moment I remember how privileged I am, how privileged my children are.

Many of the children I see playing on the train won’t have half the opportunities my own will enjoy. Their happiness will be assaulted systematically, their future jeopardized. It is of little consolation to think that if their mothers and fathers can still carry themselves with dignity and pride, and find happiness among their daily struggles, that their children will also find a way to survive the system, and perhaps, thrive. Something has got to change.

Maybe we should start by giving the benefit of the doubt to youth of color. Next time we see a Black or Brown kid gunned down by the police —for it will happen again— we should look past beyond the pictures with gangsta poses, real or not. Just put yourself in Michael’s, or for that matter, in any Black or Brown kids’ shoes, and think about how would you like to be denied a chance in life, to be deemed a threat, and to in fact have your life terminated, and then be deemed a thug “who had it coming.”

This is in no way a special treatment but equality—the equality of being presumed innocent, the equality of not having to live with the fear that you will be targeted by the police because of your complexion or your accent. Yes, this is about equality and not any special treatment.

As for my unfriended “friends,” I hope that it does not take for them to move to the contiguous 48 states to realize their own white privilege while in the island and to understand why we need to denounce and renounce it—for they or their very own children could be Michael Brown or Eric Garner. Or countless others.

***

Harry Franqui-Rivera is a historian, a blogger and a researcher at the Center for Puerto Rican Studies, Hunter College, CUNY. He has a forthcoming book, “Fighting for the Nation” on the Puerto Rican experience in the Spanish and U.S. military. He has recently published in online magazines on the topic of Puerto Ricans in the Korean War and the Diaspora. You can follow him @hfranqui.

Excellent article! Gracias por el post!

This is an excellent essay and I could not agree more. I am always amused when my fellow Puerto Ricas born and raised on the island encounter racism on the mainland. Inevitably, the reaction is never “. . . you are a racist jerk.” Instead, it is always “don’t be racist against me, I am not like ‘those people,’ I am white like you.” Keep up the good work, Harry. We need more voices like yours.

[…] like Hector Luis Alamo, Susanne Ramirez de Arrellano and Roberto Lovato, plus other top-notch essays about politics, race, identity and history. The future of LatinoRebels.com is brighter than ever, […]

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.