Latinos are receiving increasing attention in American politics. Candidates and their campaigns must decide how best to reach out to this growing community.

Trump has chosen to double-down on anti-Mexican rhetoric, but other candidates have chosen another language altogether. Democrats and Republicans alike have chosen to address Latinos in Spanish.

Hillary Clinton tweeted how to say “Go Hillary in Spanish.” With an obvious slant toward a Mexican dialect, the first option was “Oralé Hillary.”

How to say “Go Hillary!” in Spanish. Cómo decir “Go Hillary!” en español. pic.twitter.com/ssifEcHJ1F

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) July 25, 2015

Embarrassingly for Hillary, the accent in órale is on the O and not the E. The Clinton campaign took down the tweet a few weeks later and replaced it with one with no accent (a common misspelling in Spanish).

She has also been criticized for her Facebook post containing three pictures with the caption “¡Cómo pasa el tiempo!” Her post came on a Thursday, participating in “throwback Thursday” or “#retrojueves.” Her use of Spanish was seen as a crass grab at–instead of a meaningful outreach to–the Latino community.

https://www.facebook.com/hillaryclinton/posts/948746665181863

Just yesterday Martin O’Malley’s campaign sent out a tweet in Spanish calling for an end to the detention of mothers and children crossing the border in need of asylum.

Somos una nación generosa y compasiva. No deberíamos encarcelar a mujeres y niños refugiados. #EndFamilyDetention pic.twitter.com/k7y0m84mJi

— Martin O'Malley (@MartinOMalley) August 11, 2015

In a nearly 30-minute interview, Jeb Bush spoke fluently with Telemundo’s José Díaz-Balart on issues ranging from immigration reform, Donald Trump, meeting his wife in Mexico, and the discrimination his interracial children experienced. Republican presidential candidate Marco Rubio, a Cuban American, has addressed voters in Spanish, too.

The growing use of Spanish among powerful politicians has left other politicians exposed. Ted Cruz, a Cuban American and Republican presidential hopeful, does not speak Spanish. That did not keep him from portraying himself as a “Hispanic first” in a Spanish-language ad:

Rising political star in the Democratic Party and possible vice-presidential candidate Julián Castro has taken flak for his inability to speak Spanish. One senior Clinton staffer scoffed at Castro’s inability to speak Spanish and implied that this would limit his appeal to the Latino community. This led to an MSNBC headline asking “Can You be a Latino Politician if You Don’t Speak Fluent Spanish?” The answer to the question, of course, is yes.

The use of Spanish in American politics is not inconsequential. The United States is now the second largest Spanish speaking country in the world, second only to Mexico. The Latino community comprises 17.4 percent of the total population, and that growth is expected to continue in the coming decades, reaching nearly one-third of the population by 2050.

Spanish language use among the Latino population is significant. In 2015, 70 percent of Latinos spoke Spanish at home, while only 29 percent spoke only English at home. While fluency is expected to decline over multiple generations, projections for 2020 are still at 66 percent speaking Spanish at home.

The use of Spanish in American politics is not a recent phenomenon either. As early as the 1820s, Anglos making their way into what was then northern Mexico learned Spanish to make influential social and economic connections. Jim Bowie, creator of the Bowie knife, called himself “Santiago Buy” in New Mexico before moving to Texas to join the Texas Revolution.

Settler Stephen F. Austin learned Spanish to make connections to influential Tejano ranching families in Texas. In a letter to the Mexican government in the early 1830s he began in fluent Spanish: “Yo el ciudadano Mexicano Esteban F. Austín….”

Tejanos like Lorenzo de Zavala, Juan Seguín and José Antonio Navarro supported the Texas Revolution because they were convinced, with the help of people like Austin and others, that it served their economic and political interests. After 1848, with the end of the U.S.-Mexico War, the Southwest became American territory and the many Mexican inhabitants became Mexican Americans, citizens of the United States.

By the late 19th century, ethnic-based machine politics emerged across the United States in industrialized cities like Chicago and New York, but also spread in South Texas. Machine politics entailed well-funded, well-connected strongmen persuading large ethnic communities to vote for either party through unethical rewards or outright intimidation. These machines could help their communities in receiving public services but often exploited them for their own personal gains. Mexican-American poet and scholar Américo Paredes wrote sardonically about this practice in his 1935 poem “The Mexico-Texan”:

Elections come round and the gringos are loud / They pat on [his Mexican-American] back and they make him so proud / They give him mescal and the barbecue meat, / They tell him, ‘Amigo, we can’t be [defeated].’ / But after election he no gotta [friend], / The Mexico-Texan he no gotta [land].

At the same time that Paredes was writing about the underhanded and questionable machine politics of South Texas, a new generation of Mexican-American political leaders was coming onto the scene in South Texas. Politicians and leaders like José Tomás “J.T.” Canales of Brownsville and Alonso S. Perales, Andres de Luna and Santiago Tafolla of San Antonio won local offices and started civic organizations like Order Sons of America, Order Knights of America and the Latin American Citizens League. In 1929, these three groups merged to form the League of United Latin American Citizens (LULAC). Importantly, LULAC chose to limit its membership to only U.S. citizens and chose English as its official language, even though many of its members only spoke Spanish. They did this in the naïve belief that English would grant them greater social acceptance. It didn’t, but in the debates leading to the establishment of LULAC, one member explained that they hoped LULAC’s ambitious new cultural and political goals would:

serve to give a country to our children, who otherwise each time they thought of us would say: They lived as [pariahs], and they left us this sad inheritance.

The modern usage of Spanish as outreach to the Latino vote was the Viva Kennedy campaigns of the 1960 election. By then a new political generation had arrived. Politicians like Henry B. González, Albert Peña, Ed Roybal and Hector P. García were paving the way for increased political participation of Mexican Americans. In California, Ed Roybal had created the Community Service Organization (CSO), but it was in Texas that the burgeoning political class was growing in clout.

Beginning in 1959, González, Peña and García put together a plan to harness the Mexican-American vote in support of the John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson ticket. The “Sleeping Giant,” as the Mexican-American community was called then, had not yet awaken its electoral power. Before the campaigns González and Peña had campaigned in Spanish, giving speeches, writing newspapers articles and giving radio addresses. But never before had a national campaign directed its attention at the Spanish-speaking community.

The soon-to-be First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy appeared in a political ad speaking in Spanish, asking her “queridos amigos” to “votar por Kennedy.” The Viva Kennedy campaigns succeeded in winning the Latino vote. Kennedy received 85 percent of the national Hispanic vote and 91 percent in Texas, the state with the largest Mexican-America population. The Mexican-American vote pushed the state of Texas to the Kennedy-Johnson ticket and effectively won them the White House.

However, the Viva Kennedy groups ended with disillusionment in many circles. The leaders had hoped that their loyalty to the Democratic Party and delivering the decisive Mexican vote would be rewarded by the Kennedy administration with meaningful and influential appointments. Only Raymond Telles, the first Mexican-American mayor of El Paso, was awarded with an appointment, as the ambassador to Costa Rica. It seemed that even though mainstream politicians were speaking Spanish, they were speaking past Latinos.

Frustrated, Albert Peña went on to form the Political Association of Spanish Speaking Organizations (PASO) in 1962, which would lead a Mexican-American takeover of a five-seat city council in the segregated Texas town of Crystal City. PASO used more activist political slogans than the previous Viva Kennedy campaigns and was more militant in its approach to organizing. Aided by the Teamsters Union, PASO recruited voters by building on the shared interests of a “Mexicano” community.

It worked. In 1963, Crystal City elected its first all Mexican-American city council. Many perceived Peña’s new group as too radical and Hector P. García and his American G.I. Forum started to distance themselves from PASO, accusing them of being communists.

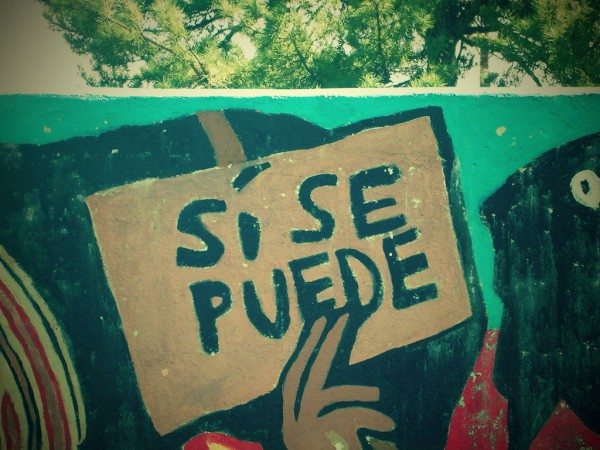

By 1965, a new generation of young people was growing politically aware and culturally conscious. Calling themselves Chicanas and Chicanos, they used a mix of both English and Spanish to emphasize their bilingual and bicultural realities and articulate their concerns. The most iconic and, perhaps today, most cliché phrase of the Chicano Movement was “Si Se Puede.”

Started as an organizing phrase by the United Farm Workers led by Cesar Chávez and Dolores Huerta, the phrase at the time was a radical rejection of racist beliefs about what Latinos could and couldn’t do. Stereotypes about Mexican passivity, lethargy and stupidity were common throughout the 20th century, and many believed them into the 1960s and 1970s. Many planters in California believed that Mexican Americans did not have the mental capacity or political understanding to strike for better wages. To yell “Si Se Puede”–“yes we can”–was a war cry adopted across the country by young Mexican Americans who were not part of the UFW strike or boycott but heard the message nonetheless. In many rallies across the Southwest two of the most important slogans of the Chicano Movement were yelled—one in Spanish, “Si Se Puede”; the other in English, “Chicano Power.” Both spoke to a new politicized generation.

As the halcyon days of the ‘60s and ‘70s died down, the ‘80s brought with it a new label–“Hispanic”–and a new political climate of moderation and conservatism. The appointment of Henry Cisneros to the Clinton administration in the ‘90s and his eventual fall from grace brought increased attention to the Latino community. But it was a young singer from Corpus Christi, Selena Qunitanilla, who brought the most attention to a growing bilingual Latino community, winning acclaim for singing in both English and Spanish.

The first decade of the 2000s brought Spanish in politics back into the spotlight. In the 2000 election, George W. Bush gave more attention to the Spanish-speaking press than other opponents and garnered 40 percent of the Latino vote, a high-water mark that most Republican candidates today can only dream of reaching. In the 2002 Texas gubernatorial race, Democratic nominee Tony Sánchez challenged Republican Rick Perry to a debate in Spanish.

In March of 2008, Barack Obama visited San Antonio and began his speech with the iconic phrase “Si Se Puede,” which had by then lost much of its political edge. The phrase “Obamanos” (roughly translated as “Let’s go with Obama!”) could be found on bumper stickers across heavily Latino areas in the United States. Then, in 2009, President Obama showed his limited range of Spanish, wishing the nation a happy “cinco de cuatro,” or a happy five of four, instead of Cinco de Mayo. By then Obama, who had received a significant share of the Latino vote, was on track to double the amount of deportations of unauthorized migrants in his first term that the Bush administration had in two terms. It seemed as though Obama not only misspoke, but misstepped politically.

The growing use of Spanish in the lead up to the 2016 election shows that the Latino community is no longer the “sleeping giant” of the ‘60s and ‘70s. Hillary Clinton’s tweets have been calculating. On July 13, 2015 she wrote:

"Para el Señor Trump, solo tengo una palabra." pic.twitter.com/7CJnin3aGh

— Hillary Clinton (@HillaryClinton) July 13, 2015

Much of Castro’s and Rubio’s political potential is based on the fact that they are both Latino. One speaks Spanish and one does not. One is Mexican American and one is Cuban American, and they represent the different histories of their Latino communities.

This is what is lost in the larger political understanding of the Latino community—it is a diverse community. Having Hispanic candidates does not mean the Hispanic population will go out blindly and vote for them. The notion that ethnic groups simply vote for the person with similar skin pigment or language skills is one that confuses the complexities of the politics of identity with a coarse identity politics. Latinos are not new arrivals who cannot speak the language. In fact, they speak multiple languages. More important, they also understand the doublespeak of American politics.

Latinas and Latinos are not blind either, and they can see a window dresser in an empty suit.

An earlier version of this article appeared on Commentary & Cuentos.

***

Aaron E. Sanchez received his Ph.D. in history from Southern Methodist University. You can connect with him @1stworldchicano.

ok

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.