The word chicano has existed in the English lexicon since 1911. During the ’60s and ’70s, that term became a symbol of pride for the Mexican Americans who were confronting the struggles of prejudice and self-identification, an answer to the always confounding question: “Who am I?” In the decades that have passed, chicanismo has been used less and less in the mainstream, yet it still evokes the same sense of pride for many. This follows the stories of two groups —the old-school Chicanos and the new school— to explore how the word has evolved over time.

Cesar Chavez mural in San Diego (Credit: Jay Galvin/Flickr)

This Open Land

Like so many others that leave their parents’ homes to go to university, Eduardo Arenas experienced independence like never before when he went to the University of Southern California in Los Angeles. With no curfew or chores, he felt as though he had uninhibited freedom.

But with that newfound independence came a lack of identity. How would Arenas define himself? At the time it didn’t bother him. He knew he was Mexican, and that was enough.

But then the university clubs and organizations approached him —fraternities, the Latino Business Students Association, Movimiento Estudantil Chican@ de Aztlán (MECha)— vying for Arenas’ affection, hoping to shape his character and his persona. Eventually, Arenas chose to join MECha (mostly because the girl he was dating was going too, he says). But Arenas was still reluctant.

“After a few years, I remember feeling like, ‘this is whack,’” Arenas says. “I’d be like, ‘I don’t need to go to MECha to know I’m Mexican. I don’t need to be fed beans to be reminded of that shit.’”

Ironically enough, Arenas had the same kind of rejective attitude that initially shaped MECha and the Chicano Movement in the first place during the 1960s. The movement thrived in confronting the negative stereotypes of Mexican Americans through political consciousness in a multitude of platforms, from land reform to reappropriated historical narrative. The “Aztlán” in MECha’s name refers to the Southwestern United States, which Chicanos— who identified as neither Mexican nor American — claimed as their promised land.

But Arenas was a brand-spanking-new adult; he didn’t need to be told how to act. Besides, it had been decades since the revolutionary ideologies of chicanismo were formed.

Back Then

Phoenix, AZ (Credit: Kevin Dooley/Flickr)

José Andrés Girón’s eyes are focused on his black coffee and tuna melt at the bar, but his mind is flickering through memories of his 40-plus years as an artist. He takes another bite of his sandwich, and in between chewing, the memories of his heyday in the 70s —when he was with Movimiento Artístico del Río Salado (M.A.R.S.)— begin to flood out of him.

“There was a smaller artist community,” Girón says. “We didn’t have a place. In the early days we just did it in the parks or the streets.”

As far as non-white art went in Arizona, M.A.R.S. was the source. Girón describes the Chicano collective like a group of guerrilla artists, who had “militaristic” sensibilities and acted like “eagles,” having to find ways around underrepresentation.

As Susy Buchanan wrote for the Phoenix New Times:

By all accounts, MARS was for many years a dynamic, energetic, edgy experience. The strong personalities of the artists involved, and their very different perspectives on just about everything, were harnessed because they all believed so strongly in the mission of MARS, former members recall.

Girón was one of them. His paintings of Aztec warriors, mariachis and wide-eyed children are images solidified as representations of Mexican-American identity, and thus a large part of M.A.R.S. Girón hasn’t stopped painting or having a fist-in-the-air kind of resilience. BUt as time passed and the world entered a new century, M.A.R.S. couldn’t keep up.

Again, Buchanan:

Lack of funding and an overall sense of fatigue by longtime members factored in, as well as a sense that perhaps the original idea had run its course —that the Movimiento in MARS, the force that propelled the cooperative through the late ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, had long since stalled.

“We went our different ways,” Girón says. “Things change. A lot of little art groups splintered off from that one.”

One of those splinters became the Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center, an artistic gallery and workspace in downtown Phoenix where Girón acts as the artist-in-residence and lead curator. For the past six years, he’s been working non-stop to make ALAC the kind of place he’d always wanted to show his work as a younger man.

Rejecting the Dominant Culture

University of Southern Califronia (Credit: John Liu/Flickr)

As little as he thought of MECha during his first years at USC, Eduardo Arenas thought even less of the overbearing culture of white affluence. Today, 12 percent of USC students are Latino, and the school’s surrounding neighborhood have a median income of less than $20,000. Sixteen miles away lies Bel Air, where 83 percent of residents are white and the median household income is at least 10 times that of USC’s neighborhood.

Arenas wasn’t a Bel Air guy. He was East L.A. born and bred. So after a while, the principles of MECha began to look increasingly appealing.

“You reject that dominant culture and you confront the social injustice. You wanna be part of something, so you go to your roots,” Arenas says. “My roots came out of chicanismo. I got empowered.”

Arenas’ roots grew and thrived through MECha, its speakers and its events—so much so that Arenas sculpted his entire identity around being Chicano. If anyone ever asked Arenas about his heritage, his ethnicity or his personage, the answer was always the same: “I’m Chicano.”

That’s the answer Arenas gave to the customs officers at the airport when he got the chance to travel to Brazil.

“I remember them being like, ‘Where are you from?’ and I’d say, ‘I’m Chicano,’” Arenas says. He said it proudly, wearing it on his sleeve like a medal. But the officers replied: “That’s nothing, sir.”

“It Works. But It’s Not Easy.”

The Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center is a non-profit, and a fairly new one at that, so it is by no means a cash cow. But one of the reasons ALAC hasn’t fallen apart, says José Andrés Girón, is because of the organization’s president, Linda Torres.

“I tell her, ‘Slow down. You’re gonna wear yourself out,’” Girón says. “Sometimes she’s juggling three or four different things at the same time.”

Torres credits her work ethic to her Chicana-centric youth. She worked alongside César Chávez, Dolores Huerta and the United Farm Workers, using her performance art —specifically, dance— as a means of activism in the ’60s and ’70s.

“The profile you see is that commitment to old school,” Torres says. “You have to dig your heels in and get to work.”

Torres proudly identifies as an activist and Chicana. But her self-identity isn’t easily marketable. The Chicano identity has never been static; the only consistent aspect of the term is that it is continuously ambiguous (many Chicanos would attest). In the 1991 play A Bowl of Beings by Latino theatre troupe Culture Clash, Che Guevara asks what “Chicano” means, to which another character responds, “I still don’t know!”

Though the term first appeared in 1911, Chicano wasn’t clearly defined 80 years later, and in the 24 years since the Culture Clash play, it still hasn’t become explicit enough, especially to put on a storefront. That’s why Girón’s and Torres’s organization is called the Arizona Latino Arts & Cultural Center.

“It’s just a nice way to compromise with everybody,” Torres says.

Pushing Through Obstacles

Eduardo Arenas had a crisis of identity when customs officers wouldn’t call him “Chicano.” And still to this day, that word has created obstacles in his life.

This time, it’s with the band he plays in: Chicano Batman.

“With a name like Chicano Batman, we gotta go through the alleyway,” Arenas says. “We’ve gotta get a following to follow us. We’ve known that since the beginning.”

The band, a quartet of East L.A. dudes mixing Motown, cumbia and everything in between, got its name after band member Bardo Martínez sketched out a cholo version of Batman at a college party during a moment of inebriation (or clarity, depending on how you look at it).

That catalyst which birthed the name of the band has now transformed into a more official symbol: a hybrid between Batman’s logo and the United Farm Worker’s eagle. The latter half of the symbol (and former half of the band name) plays a strong role in how the guys identify themselves and their music.

“We have a connection to our families, our city and our history,” Martínez says. “I mean our name is kind of an ode to the Chicano Movement with the UFW and all that stuff.”

Back in PHX

Linda Torres and the other founding members of ALAC wanted to make sure that the space they occupy and the organization would be sustainable, which meant finding a name that could be an over-encompassing nod to Latinos, Chicanos, Mexicans and indigenous artists.

“I use the terms interchangeably, but they’re not all the same,” Torres says.

So around 2007, 12 arts groups got together to answer this question: how to make sure the state of Arizona recognizes the efforts of artists and the contributions of Latinos, mexicanos, Chican@s and indigenous peoples? Their answer is what is now the Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center.

The center sits on the corner of Second Avenue and Adams Street, across from the Phoenix Convention Center and the Hyatt Regency Hotel, smack dab in the middle of downtown Phoenix. It’s prime real estate. But 147 East Adams Street had already been a space that attempted to answer the question Torres and the art groups were confronting.

For almost 20 years before ALAC took over that address, there was another art museum focused around the work of Latinos, called Museo Chicano. Despite having operated for so long, there’s barely any information about it that exists. What little information that does exist about Museo Chicano would suggest that the museum’s owners had the same intentions and goals that ALAC did.

So why did it close?

“I’m not really sure,” Torres says. “I heard the owner wasn’t taking care of the space anymore, and that she had some sort of falling out with the city. But I don’t know anything more than that.”

According to the Arizona Republic, Museo Chicano was operated by a woman named Elizabeth Gauna who said the museum closed due to an expired lease with the city. There has been no mention of Elizabeth Gauna nor of the Museo Chicano’s legacy since it closed, and barely any mention of it when it was in operation.

Museo Chicano sat on Adams Street for 19 years; it sat in Mercado near Van Buren and Seventh streets for seven years before that. But as far as most people know, it simply never existed.

Social Commentary?

The Chicano-centric mindset that drove Eduardo Arenas in his college years hasn’t gone away by any means. But it’s not a soapbox for him either.

“Now, man, I’m really proud to say I’m a human being—independent of a lot of categories that people wanna put me into,” Arenas says. “That’s not to belittle the Chicano Movement, but when you start expanding your world, your ideology kind of shifts.”

That’s the same mindset Arenas, Bardo Martínez and the rest of the guys in Chicano Batman have when it comes to their band name.

“The name could almost be perceived as something different from what the band is, and I think there’s some beauty in that,” Martinez says. “Like ‘Red Hot Chili Peppers,’ it’s like that, you know? I think that’s how a lot of people see it.”

Like Arenas says, it’s not as though the band is disregarding their heritage. But they also know not to take it too seriously either. They know that for a lot of people, it’s not necessarily an homage or political commentary; it’s a brand.

“The name itself gets people to shows without even knowing what kind of music we play,” Arenas says. “The logo gets people to buy the shirt without even knowing what it is. But they’re buying it.”

Enough people must have bought the shirt. Since interviewing the band in October 2014, the audience of NPR’s Alt.Latino podcast voted them as one of the best bands that year. They opened for Jack White on his latest tour. They played Coachella for the first time.

Their work seems to have paid off, something Bardo Martínez has known for a while.

“People are hungry for culture, and at the end of the day, a lot of culture is consumerism,” Martínez says. “It’s not about where you come from or what your roots are.”

Challenges

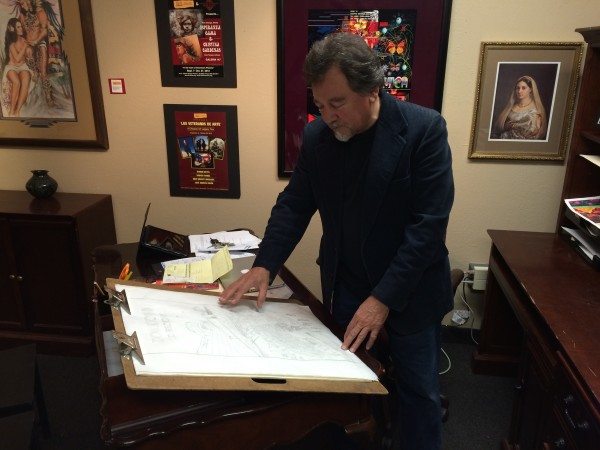

ALAC President Linda Torres and Visual Arts Committee Chair José Andrés Girón stand in front of the Arizona Latino Arts and Cultural Center in downtown Phoenix, Arizona (Credit: Steven Totten)

Linda Torres reflects on ALAC’s opening with conviction, and for good reason. The arts and cultural center opened in 2009, during the economic downturn. Torres says it was “the worst time possible” to start a business, let alone a non-profit arts organization.

But as luck would have it, the City of Phoenix —which owns 147 East Adams Street— was more than ready to market its (or market to its) Latino population.

“The City is our biggest supporter in my opinion,” Girón says. “They’re gracious: we just have to pay overhead. They know that it attracts tourism. They want that cultural mix, especially downtown. They want that component that’s Latino.”

As far as tourism goes, the over 16 million annual visitors to Phoenix spend over $2 billion on entertainment and recreation. Conversely, The Republic reported that in 2009, “county Latino residents spend $25.5 million just on visits to museums, zoos and botanical gardens each year.”

On the night of the grand opening, it could have been both tourists and residents alike.

“There must have been 2,500 people trying to fit in, and you just could not move,” Torres says. “Everybody and their brother and sister were trying to get in. That’s how desperate the community was for this presence.”

Now the roar that was ALAC’s opening has become something of a whimper. On Mexican-centric holidays, like the acculturated Cinco de Mayo or Día de los Muertos, the space is busy, no problem. But the rest of the time, Girón references ALAC like it’s a ghost: “The public? I don’t even think they know we exist.”

Only a third of ALAC’s founding members remain. Torres and Girón both say that’s how people in the art world work, regardless of how much they want to showcase their identity as Latinos, Mexicans, indigenous or Chicanos.

“You know, artists are pretty independent people,” Torres says. “And sitting down and promoting other artists is pretty difficult I find for artists to do. It leaves you in the shadow.”

In order not to face the same fate as M.A.R.S. or Museo Chicano, Torres and Girón have had to make due staying put in the shadow. ALAC isn’t the first group to try and promote the cultural accomplishments of Phoenix’s Latino population either, so that shadow is pretty big.

“We’re up against Valle del Sol, Chicanos Por La Causa, all these other long-standing organizations [that] are sucking up the corporate money,” Girón says. “[The corporations] already know them; they’re tried and true. They’re not gonna throw money at us.”

If it wasn’t for the City of Phoenix bearing the load, it’s pretty likely that ALAC wouldn’t be here now. For all of the Chicano-fueled passion that Torres and Girón have, for the legacy they want to leave, it’s simply not that easy to maintain a non-profit arts center seven days a week, regardless of whether or not there’s a recession.

That couldn’t be more true now, when ALAC is trying to get a bond approved for more funds to expand the 300 square feet of 147 Adams Street.

“It’s a very old building. It needs it,” Torres says. “While art is beautiful and people love it, it’s not like it’s selling day and night. It’s not food you have to eat.”

When Girón and Torres were younger, being Chicano wasn’t vague. It was incredibly clear what they wanted: independence, recognition and, perhaps most important, respect. In the years since, minor steps have been made in order to give them —and the Latino community as a whole— that independence, recognition and respect. Despite those steps, the majority of the world, like the customs agents that confronted Eduardo Arenas, still has no idea what it means to be Chicano.

But for Eduardo Arenas and Chicano Batman, ambiguity is a common thread running throughout American culture. They don’t expect their fans to know what being Chicano means, and they seem to be okay with that. In time, it’s possible that the integration of Chicanos into pop culture will spark a closer understanding of identity.

***

Steven Totten is a multimedia editor and journalist living in Phoenix, Arizona. You can connect with him @stevenjtotten.

[…] is flourishing with bands like Grupo Fantasma, Money Chicha, Brownout. Los Angeles has Boyepongo, Chicano Batman, our homies Dos Santos in Chicago, not mention our fearless leader Olivier Conan and Chicha Libre […]

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.