I have known Chris Campanioni for almost three years. When I was editor-in-chief at Aignos Publishing, I signed him and oversaw the release of his first novel Going Down and his first book of poetry In Conversation which prior to publication had won the 2013 Academy of American Poet’s Prize. We have also collaborated on the YouNiversity Project, where we mentor up-and-coming writers on the challenges and rewards of 21st-century publishing.

I do not normally interview friends, but for the release of Chris’s Tourist Trap (or: How I Paid My Way through Grad School), I am making an exception. I read an earlier draft of the book back in 2013 and have not been able to shake it ever since. It is an exciting, daring work of art that combines all of the thematic concerns of Chris’s catalog and puts it in the context of a thriller that is equal parts exciting and ambitious. Many times, the book could easily fall into easy formula, yet Chris always takes the less traveled and more introspective path.

Tourist Trap is a rare book that excites both the intellect and the emotions, as the reader is forced to ask themselves about their own role in a corrupt landscape of capitalist greed that turns all people into commodities. It is a book that needs to be experienced as well as discussed, and so it is with great pleasure that I now have the chance to publicly express my thoughts about this wonderful book that has haunted me for two years.

What was your inspiration for Tourist Trap?

I was studying at the University of Buckingham and, like so many nights in England, at least in the winter of 2005, it was raining. I was alone and lonely; I didn’t know anyone in the country because I’d only just arrived a week or so earlier, and so I decided to write a short story about a tourist-for-hire who gets into trouble and eventually lands inside an NSA interrogation room. I just didn’t know what trouble he’d gotten into, and since I began with the scene in the interrogation room, I had to fill in the blanks.

During the process, an English professor from Lehigh University, David Hawkes —who figures into Tourist Trap, although his name is changed— read an early draft of the novel and pointed me in the direction of the Situationist International. You could say Guy Debord and Co. did the rest. Through the avant-garde artistic-political group and its various factions and figures, I was able to give the novel a historical precedent, which was important, because in order to write much of the story, I used historical data: everything from WWII-era news reports to statistics about terrorism, national security, government collusion, the drug trade in North Africa and Europe, the buying and selling of bodies and body parts, the tourism industry, and NSA surveillance (from 2005 mind you, before anyone knew our government’s omnipresent gaze was a thing).

I was just beginning my career as a journalist at the San Franciso Chronicle and I thought mainly about New Journalism, which had gone out of style before I was born. I wanted to write about the absurdities of our current cultural and political climate and trace these horrors, but I knew I could reach more people if I used the novel form as a vehicle to tell the story.

The atrocity exhibits make their appearance in this book. What was your intention with this literary device?

The Atrocity Exhibit was something I’d written into a short story called “The Fleeting Moments Between Here and There,” and in that context, it allowed me to imagine a post-apocalyptic future via fractured, moving images, literally a museum of moving images. Death meets life in list form.

Months later, when writing Tourist Trap and thinking about it as being part of some larger, interconnected series of books, I decided to continue the exhibits where they’d left off. This allowed me to make some of these connecting threads between different stories in the same universe more explicit, and it also allowed me to carry over this aesthetic —fracture, fragmentation, simulation, cinema, voyeurism— which has since become, I think, a feature of much of my published poetry and prose.

In another sense, the AEs also serve the same function as the metaphysical footnotes sprinkled throughout Going Down and Tourist Trap: they allow the reader to move outside the text and in a way participate. The nature of the exhibits are such that they signpost their own act of display: we know we are watching a performance and the performance itself is pointing this out, almost like the performance is watching itself perform; the reader is the mirror.

Just as in an actual museum exhibit, these sections are meant to arrest the narrative and its readers. It’s an interference that allows readers to provide all the context, in the same way that a painting without a caption would.

A mural in Paris featuring Guy Debord, founder of the Situationist International (thierry ehrmann/Flickr)

How does poetry influence your narratives and vice versa?

I think rhythm is the upshot which a training in poetry can give to writers working in prose. And so I think much of my prose reads like poetry: the attention to rhythm, sound and movement is always influencing and shaping (probably too much) my prose, rather than other traditional concerns like character, plot and story. In that exchange, the figural power of language that is emphasized in poetry comes into play with my prose. Tourist Trap is a good example of this, not only because the novel has several chapters written in these cinema-stills of “Atrocity Exhibits,” but also because the pace is quicker than any other novel I’ve written.

You have expressed in the past a love for the Situationist International, yet in this book they are a terrorist organization. Is the book a critique of SI, or are you expanding on the real group’s philosophy?

The book does a bit of both. The SI became the basis of the unnamed “Company” in Tourist Trap, which allowed me to reanimate a defunct organization and its values. But at the same time, this novel is a criticism of SI and moreover, any sort of ideology whose every act regresses into gesture.

I think the Situationist International was an ideal group from which to formulate the backbone of the Company in Tourist Trap because the Situationists were mainly reacting against capitalism and the society of the spectacle, spectatorship as the modus operandi of its culture instead of participation, action, contributions, literally creating situations, devoid of intent and regardless of consequence. If I was going to try and advance these notions into the 21st century, the Situationists were my way in.

The book makes heavy criticisms of capitalism and materialism and uses terrorism as a way of combating both tendencies, yet in a satirical light. How do you reconcile the satire with serious commentary? And do you see civil disobedience or terrorism as the best way of reforming capitalism?

I think satire and humor, particularly a humor ingrained in the absurd, was a decision made mainly for craft purposes. I’ve always thought the works which impress me most are the ones that can make you laugh and cry almost simultaneously, so I try to be conscious of that goal as a writer. But I don’t see terrorism as the best way —or even an option— of reforming capitalism. Throughout this novel there are a few different routes posited besides physical violence, namely Accelerationism.

All of these options are raised within the story so that they may be critiqued and eventually upended through horror and humor. The only scenario I raise in Tourist Trap that I agree with is a non-partisan belief, which might be best summed up as simply “education.” To be a writer and political is a dangerous thing. To be a writer and apolitical is even more dangerous. Art is right, left; in truth, it has only one direction and that is forward, which is something that is taken directly from a Q&A in the novel. Any sense of progress is contingent on the fact that renewal is the basis of reformation, not death.

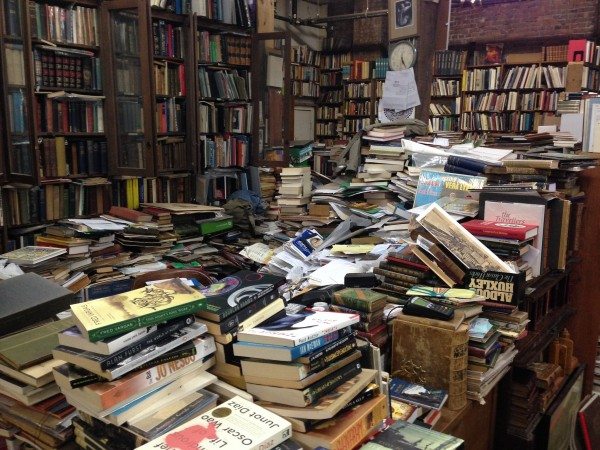

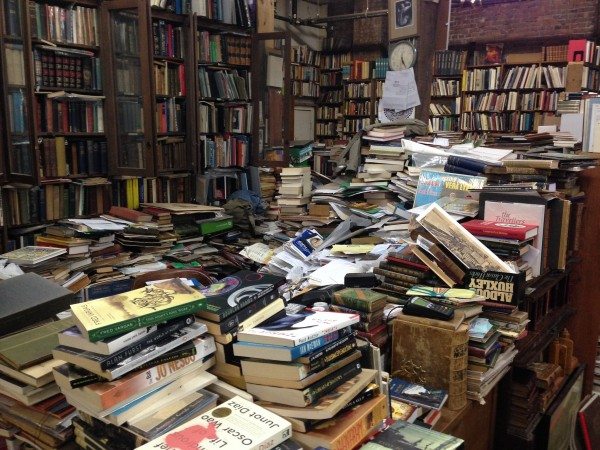

(Kyle Pearce/Flickr)

Your terrorist characters are motivated primarily by a desperation for meaning and value based on a sort of privileged malaise, reminiscent of books like Fight Club. They are marked more by nihilism than by religious or political convictions. Why did you choose that motivation over, say, white supremacist terrorism which has been growing in prevalence in recent years? How do your characters relate to the social unrest that is occurring today?

I was especially wary, as I wrote Tourist Trap, of obscuring or conflating my criticisms of the culture industry and compartmentalizing them with, say, white supremacy, or any other “singular” hate group. In reality, all of these groups are doing what the nameless Company in the novel does, which is use ideology to coerce and manipulate the individual.

Nihilism is just another excuse for these agents to engage in rampant capitalism via death, destruction and of course real estate by which they reap the profits of their destruction. But nihilism is vague, purposefully abstract. It allowed me to attack ideology, all of it, and use the culture industry —Hollywood, mass media, Wall Street, the drug trade, fashion, consumers, etc.— without singling out any stripped down version of it, whether that is white supremacy or any other political or nonpolitical faction. In this way, Tourist Trap makes it explicit: we are all complicit in this exchange.

The excuse for nihilism is merely a gesture that really has its roots in boredom. Paradoxically, boredom is the engine of desire behind every action in all my works. In this way, early Situationist ideology comes back into play. Each narrator in my own version of the coming-of-the-age genre is motivated by a utopic concern of grafting life onto the blank space. This is not only true of Going Down and Tourist Trap, but also of my most recent novel Fashion of the seasons.

Unlike Going Down, Tourist Trap is not concerned with ethnic identity. Are you trying to branch out from the Latino Lit label?

I’ve never been much of a fan of any label, as you probably could guess. But I’ve always felt the “Latin American” label is especially troublesome because of the many different identities and origins woven into a place as diverse and multifarious as Latin America. Going Down was called “Latin American literature,” and really all I set out to do was tell my story. Of course, these things are out of my hands. All I should concern myself with as a writer is telling the story, so I remind myself of that often.

All of my books seem overly concerned with identity, none more so than my forthcoming memoir Death of Art, which alternates between poetry and prose. In general, I’ve used genre to upend generic expectations.

If there is one identity that is critiqued and analyzed and which permeates the text of Tourist Trap, it is North American identity. This is because I never felt most North American until I was outside North America, alone, for the first time. You always feel your identity most when you are outside of the place in which your identity designates you. In other words, you are better able to get inside yourself when you are farthest away from yourself, or the place you call home. I think that always holds true, which is why I think this book was written so quickly and all of it except the epilogue while I was abroad.

To examine North American identity and the repercussions of 9/11 five years after the tragedy, I had to examine it through the lens of others, and their perceptions of “North American,” the role I played when I was traveling through the United Kingdom and Europe between 2005 and 2006.

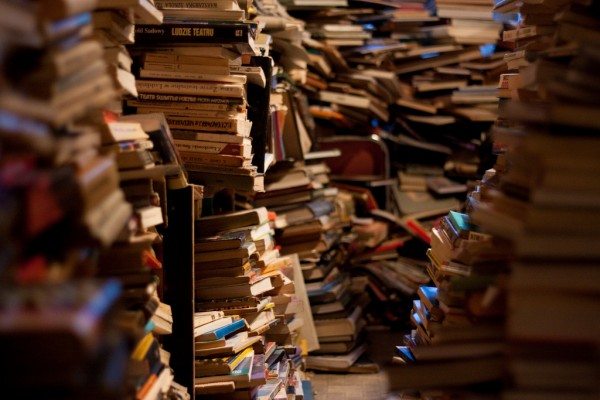

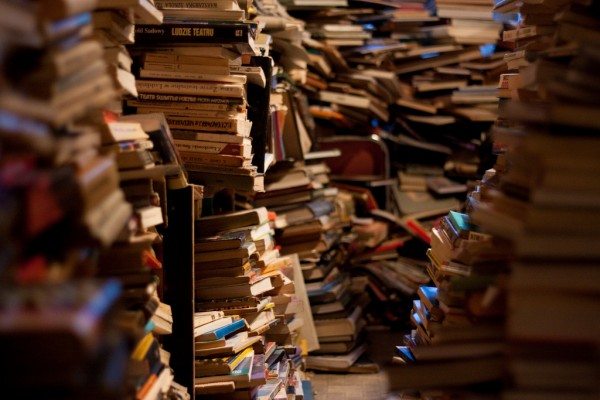

Bookstore in Warsaw, Poland (Magic Madzik/Flickr)

You said the Atrocity Exhibits are meant to create a dialogue with the reader the way paintings in a museum would. Conversation between reader and writer is a big concern of yours. How do you see this developing from a stylistic point of view, not only with your stories, but with current literary trends?

Well, I think the emphasis on several different forms of accessibility, audience contribution, and increased participation is the foundation for the kind of art that will become the eventual norm in the 21st century. We see it growing rapidly in the visual arts and in literary work as well, although at a much slower pace. How can I better include the reader in what they are reading? How can I allow the reader greater access to several different forms of reading what they are reading? These are questions I persistently ask myself as I write poetry and prose, regardless of the medium.

There’s a line toward the end of In Conversation, the book of poems that earned me the 2013 Academy of American Prize, that I think gets to the heart of this concern:

Critics want to talk about plot, about sequence, about characters. But the only element that interests me in my work is the reader. I write for a communication, between myself and anyone listening.

The role of social networks becomes integral in re-defining the relationship between artist and audience, either through re-translating the work of art into different mediums post facto (as in adapting scenes from a novel into film with the aid of readers) or letting readers access different points of the novel by way of a “behind-the-scenes” or “supplementary materials” analysis which has become so popular in film and television. As a reader, I’ve always valued context, and I think this is the basis of establishing a dialogue between readers and writer.

Going back to what you said about nihilism having roots in boredom, I’m wondering if you could elaborate both on how you define boredom. Do you see boredom as a distinctly American trait? How does boredom manifest in the American character?

Boredom has taken on many roles throughout history; its link with French Existentialism is certainly not distinctly American. But in our post-global, Internet culture, I think we can pinpoint boredom, specifically in the North American sense, as being a result of abundance. This would tie boredom in as the inevitable upshot of a consumer culture, entertainment and the surplus of options we have to live our lives.

At first glance this seems like a paradox: Wouldn’t boredom be the result of not having any options? But when there are no options, we are forced to move from the role of spectator, to the role of activist, even in the sense of being active. Tourist Trap examines both roles of boredom, from the existential concerns to the issues of overabundance and superfluity in Western culture. This is a novel that is entrenched with issues of morality, acts of free will, and ultimately, responsibility of the individual and of a culture, or the lackthereof.

When I wrote Tourist Trap I was still in college and I had never read any French Existentialism. When I encountered the work of Camus and Sartre, I felt an incredible elective affinity with them, which allowed me to see my work in a new light. I realized I had been in conversation with these authors long before I met them, and I felt validated by the grounding they provided and the language they offered to make sense of my own writing, in the same way that Adorno and Marx did while I was writing Going Down in grad school.

A cathedral in Havana, Cuba (Artur Staszewski/Flickr)

You mentioned your upcoming memoir, but you have another project that has been in the works called Letters from Santiago, which seems to be a complete break with your past works. Could you tell us some about that project: What are your intentions artistically as well as thematically? Do you see Letters as being the logical next step in your evolution as a writer?

When looking through letters my aunt sent to the United States at the outset of the Cuban Revolution, I constructed a narrative interlaced with text from her correspondence and present-day recounting of hers and my father’s experience during the revolution before they both migrated to the United States. This is the basis of Letters From Santiago, an epistolary novel that continues the story of a character close to many readers’ hearts, Ana Esther Fuentes, the mother of the protagonist in Going Down. Of course, in 1959, Ana is a child, so I’m looking forward to not only the departure in setting, but also narration. The epistolary form, too, will be a major departure from my previous work, at least as a sustaining narrative element over the length of a whole novel.

I don’t know if there is anything logical about my process or progress as a writer, but I do know that if I am entirely conscious of one thing before and during my writing process, I am conscious of trying to really make each book, whether poetry or prose, different from the last. I want every book to be a different experience, especially because I write very quickly. What’s the point of repeating things? I repeat them enough as a thematic concern in the works themselves. Let every book be an entirely new experience, with concerns that may coincide or intersect with other works, but which push them in different, often contrasting directions.

Your involvement in the YouNiversity Project and your work as a professor places you in the position of guiding many young writers on their own journeys. What do you feel, now that you’ve had several books published and have begun establishing yourself in literary circles, is the most important message you want to convey to these young artists? Put another way, if there was one lesson you could give your students and aspiring writers, what would that be?

I truly believe that aspiring writers need to stop thinking of themselves as “aspiring writers” and begin to identify themselves as “writers.” The first step to self-realization is self-acceptance, but so many writers, regardless of their age, stop short because they can’t make this connection between what I am doing, sometimes every day, and who I am. In terms of the motive behind action, I would also urge all serious writers to not forget why they write in the first place: pleasure.

To learn more about Chris, visit his website. You can also order his books on Amazon and Barnes & Noble. Tourist Trap is available for sale here.

***

Jonathan Marcantoni is a Puerto Rican novelist and co-owner of Aignos Publishing. His books, Kings of 7th Avenue and The Feast of San Sebastian, deal with issues of identity and corruption in both the Puerto Rican diaspora and on the island. He is co-founder (with Chris Campanioni) of the YouNiversity Project, which mentors new writers. He holds a BA in Spanish studies from the University of Tampa and a MH in creative writing from Tiffin University. He lives in Colorado Springs and can be reached at jon.marcantoni@gmail.com.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.