(Emilien ETIENNE/Flickr)

Mexico celebrated its 205th year of independence with the traditional grito. Yet, on the 16th of September, 2015, some wonder whether Mexico has anything to celebrate, whether the people of the nation are independent or free. Under the current president, Enrique Peña Nieto, politically-expedient disappearances have increased in the nation. In the case of the 43 disappeared school teachers, multiple mass graves were found — none of which held the bodies of the teachers and instead brought to light the murder of so many unknown and unnamed people. Drug violence continues, political corruption is endemic, and popular political disaffection continues to spread.

Political disenchantment on Independence Day is common, a day that begs for introspection and remembrance. On the same day in 1918 a Mexican journalist, suffering from the same disillusionment wrote, “the 16th of September … will be a day of pain; for the inhabitants of the biggest cities of Mexico it will be a day of desecration.” He continued, “This is not the time to sing, nor the time to give in to vain laments. We must prepare to return to our land; we will restore profaned altars; we will recover our country.”

Interestingly, the author of the article was not writing from Mexico City, or the industrial cities of the North. He was writing from San Antonio, Texas. He was part of an elite exile class living in the United States, displaced by the radicalism and violence of the Mexican Revolution. Of course, journalists and rich businessmen were not the only ones who fled to the U.S., both then and now. Millions of Mexicans made their way northward, and between 1920 and 1930 the ethnic Mexican population in the United States grew over 100 percent.

Pancho Villa’s forces during the Mexican Revolution (ABQ Museum Photo Archives/Flickr)

The Mexican Revolution began in 1910 as an answer to the political repression of the Porfirio Díaz dictatorship and as a response to the disrupting effects of industrialization. The movement that coalesced into the revolution was a shaky cross-class alliance between elite groups who wanted more profit and power, and rural and urban working-classes who were experiencing increased poverty and economic uncertainty. It was not a lasting coalition, and the revolution quickly devolved into a bloody civil war. As the waves of migration grew, both elite and poor Mexican nationals found themselves in the United States.

While in the United States, Mexican nationals started to create a vision of a dislocated population that represented the essence of the nation, even though they were no longer residing in it. They were a Mexico outside of Mexico, a México de afuera. As such it was their duty to return to Mexico and redeem the nation from political corruption, violence and patriotic despair. One journalist wrote the Revista Mexicana in September 1918:

And comparing our sadness with those that have stayed in Mexico, we have to confess that if we suffer from the nostalgia of our land, they suffer the inconsolable nostalgia of the national spirit. They are uprooted in their own land, and they wait in their villages and cities for the soul of the Patria to return to the Patria. They do well, those poor people, in waiting for Mexico to return to Mexico. We, for our part, should consider our return to the Patria as a duty and not a desire. We represent the national thought in its essence and the energies and incoherent aspirations of a nationality that waits our return like salvation … Emigrated Mexico will redeem enslaved Mexico.

If Mexicans living in the United States did not return to redeem Mexico, then they deserved “the curse of history for not bequeathing to their sons the inheritance of an intact and autonomous country which they had received from their parents.”

In an era of economic transformation and demographic dislocation, many wondered about the status and future of ethnic Mexicans in the United States. Many people believed that Mexican nationals and Mexican Americans in the United States owed their political and cultural allegiances to Mexico and not to the United States.

The Mexican consul of San Antonio, Enrique Santíbañez, wrote in 1930:

Allow me to say to the Mexicans, my co-nationals, that they should always remember that they live in a foreign nation, that they came by their own choice to the United States and that they have no right to disturb the existing social conditions here [and] if luck is bad in one place, they should seek their fortune in another or return to their country.

“Mexican workers await legal employment in the United State,” Mexicali, 1954 (Public Domain)

Anthropologist and former Mexican Minister of Education Manuel Gamio, who studied Mexican migration in the late 1920s and early 1930s, concluded that Mexican Americans were “a people without a country.” Perhaps it was the character José in the 1934 novel Los Pochos who most accurately described what many thought of Mexicans and Mexican-Americans in the United States when he asked his sister: “¿Y tú qué eres?” “Una pocha infeliz que ni a ‘bolilla’ llegas” was the answer. Most of the Mexican nationals who believed that there was no place for Mexicans in the United States believed it would only be a matter of time before they all returned to Mexico. The mass deportation campaigns of the 1930s might have signaled that they were correct.

There were differing opinions about Mexico in the ethnic Mexican community. A new political outlook was taking shape in Texas and the Southwest. There were various groups that wanted to put aside the ideas of Mexico and prove their true and loyal allegiance to the United States. Andres de Luna, president of the Order Sons of America, wrote to his membership in San Antonio:

Once and for all we want to stop being beggars of a nationality, men without a country, an inconsistent and disoriented racial element, or pilgrims after various generations who live in an incomplete state of uncertainty when dealing with his interests regarding nation and citizenship.

According to the OSA and, eventually, groups like LULAC, it was time to put Mexico in the past and forget about their problems and politics. Mexican Americans’ future was in the United States, and they should be concerned with being recognized as Americans and concerned about Americans only. A radio address in the 1930s brought this point home: “In this small piece of land in the border states of the United States, the tricolor flag, the glorious country of our ancestors, does not reach out to cover us.”

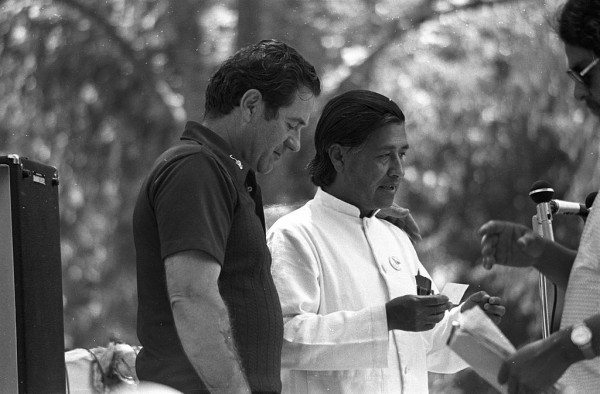

On the right, civil rights leader Cesar Chavez at UFW rally in Delano, California in 1974 (Wikimedia Commons)

This influential political outlook would maintain prominence until the 1960s and 1970s, when Chicana and Chicano activists challenged its limited notion of human connections. They believed that the essentializing of identity based on political citizenship instead of more humane imaginings produced exclusive policies and perpetuated prejudices. They believed that Mexican Americans and U.S. Latin@s had global histories that gave them global identities.

While Mexico celebrates its independence, a date that coincides with the beginning of Hispanic Heritage Month in the United States, many will ask what the responsibility of those people of Mexican descent living outside the country should be. We are living in another moment of economic transformation and demographic change. We should not fall back into the habit of believing that being a citizen means we are only concerned about those in our nation. Citizenship, especially U.S. citizenship, provides us with very real protections, privileges and powers. But we must also be concerned with world events and global processes.

As children of diaspora, of displacement, as daughters and sons of inequality, our history and experiences gives us transnational connections to and understandings of these issues, just as they connect us to global issues. We are the 43, just like we are the Syrian refugees in Europe. We do not need to redeem Mexico with our return. But it is our responsibility to push for social justice, here and in the world. Let’s not to use our migrant story to perpetuate a myth of American exceptionalism, but to remember the fear, the desperation and the starvation of dislocation to create more human policies.

—

An earlier version of this article appeared on Commentary & Cuentos.

***

Aaron E. Sanchez received a Ph.D. in history from Southern Methodist University. You can connect with him @1stworldchicano.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.