March for Science (MfS) is a USA-based movement protesting the Trump Administration’s anti-science policies and actions. This includes appointing non-scientists and anti-climate change campaigners with conflict of interests in key policy roles, gag orders on climate and science organizations, a vow to cut federal spending by slashing funding and hires, removing information about climate science from the White House website and a threat to the integrity of the peer review process, amongst many other worrying decisions. Scientists have resolutely stated that these interventions will “lead to bad public policy.”

The Trump Administration has similarly issued cuts and gag orders to organizations in the humanities and human services, including cutting aid to global organizations offering abortion services and temporarily suspending visas to people born in seven Muslim-majority countries. The latter so-called “Muslim ban” received a stay that Trump subsequently appealed then ultimately dropped. Having promised to revise it as a “very comprehensive order to protect our people,” the new visa an immigration restrictions target six Muslim-majority nations. In its first iteration, the ban affected science collaboration and the safety of researchers, especially scientists from Iran. To date, over 43,000 academics have petitioned against the original decision, including 62 Nobel Laureates, 146 prestigious Prize awardees, and 521 Members of the various National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Arts. Over 150 professional associations collectively protested. More than 160 biotechnology leaders signed a similar letter and over 100 technology companies joined in a lawsuit against the original Executive Order. This political issue harms science because it hampers the people and networks of collaboration without whom science is not possible.

Immigration raids have also escalated and broadened the groups being targeted. A hand-me-down from the Obama Administration, this is a science issue too, affecting community health and infant well-being. Latin American students and scientists live in communities ravaged by fear of deportation. This comes alongside President Trump’s desire to build a wall to separate the USA from Mexico, a decision that will stall international science programs, hurt wildlife and destroy habitats, as well as cause other environmental damage. Then there is the potential ecological disaster on sacred Native American lands through President Trump’s revived approval for the construction of the Keystone XL and Dakota Access oil pipelines. This is of special concern to Indigenous scientists and their communities, whose knowledge science cannot do without. Then there is the threat to the American Health Care Act, which will affected disabled people most of all and deepen poverty further along racial, gender and class lines. Scientists with disabilities have made a tremendous contribution to research and they use scientific knowledge to deliver services that benefit all of society. Such a massive impact on health is a hazard to science. Similarly, the Transgender Bathroom Bill, which has zero scientific and civic legitimacy, will impact the safety and wellbeing of transgender people not just in Texas, but everywhere, bringing additional risks to transgender scientists whose careers are already negatively impacted by discrimination.

Science is under threat; but the impact will be more acute for some scientists over others. It isn’t just the natural and physical scientists; social science organizations are actively encouraging their members to participate in the march. Such wide-ranging disciplinary opposition to the Trump Administration’s science policies makes any science protest a broad-reaching, cross-disciplinary scientific endeavor.

Origins of the March

Inspired by the impact of the Women’s March, March for Science (MfS) emerged from a series of social media conversations. The ScienceMarchDC Twitter account was set up on January 24, and a Facebook page three days later. Their follower base ballooned from a couple of hundred people to thousands. At the time of writing, the Twitter account has 337,000 followers, the public Facebook page has more than 393,000 likes, and the private Facebook community has over 840,000 members. There are currently 360 satellite marches being organized in various American states and in many cities around the world.

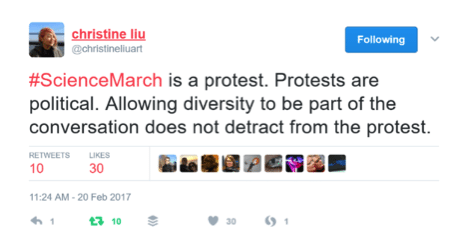

The MfS organizers go to great pains to separate science from politics, and science from scientists, as if practice and policies are independent from practitioners. For example co-chair and biology postdoctoral fellow Dr Jonathan Berman says: “Yes, this is a protest, but it’s not a political protest.” Another co-chair, science writer Dr Caroline Weinberg, recently told The Chronicle: “This isn’t about scientists. It’s about science.” These sentiments strangely echo other highly publicized opposition to the march, and are being replicated in some of the local marches. The idea that a protest can be “not political” and that science can be separated from scientists are both political ideas. These notions privilege the status quo in science, by centring the politics, identities and values of White scientists, especially White cisgender, able-bodied men, who are less affected by changes to the aforementioned social policies.

The topic of diversity has dominated online conversations between many scientists across different nations who are interested in making MfS inclusive.

Even as the movement gained swift momentum, the leadership and mission were unclear in one key area: diversity.

Diversity

I am using the term diversity here, because this reflects the language of MfS, however it’s important to untangle this meaning. In the scientific literature, diversity is an umbrella term that encompasses three distinct concepts. First, equity: identifying barriers, issues and solutions to structural disadvantage. Second, access: creating, measuring and redesigning opportunities to enhance participation by underrepresented groups. Third, inclusion: actively seeking out, valuing and respecting differences. Additionally, the concept of intersectionality specifically addresses how gender and racial inequalities are interconnected and compound other forms of social exclusion, such as sexuality, disability, class and so on. Intersectionality is central to understanding why science is not an even playing field.

Two days into its life, the MfS organizers were reproducing gender stereotypes of science as part of its promotion of the march. They were also ignoring the labour and activism of people of color in science.

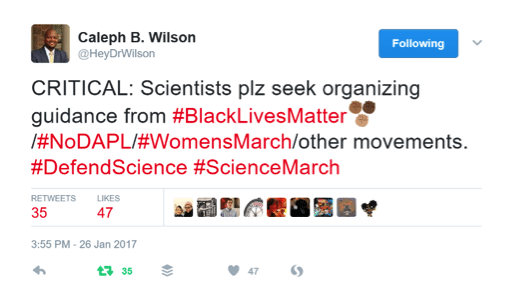

The organizers responded that they were listening to “complaints” about diversity, but they have struggled to proactively redress the serious scientific criticisms about their approach. By the 21 January they published a diversity statement that excluded disability. As pressure mounted from underrepresented scientists maligned by the march organizers’ “apolitical” stance, on January 25, the MfS organizers announced a “diversity committee and diversity steering committee” but did not immediately provide further details. Scientists were especially concerned that the organizers were not connecting with other longer-established activist groups with a better appreciation how other social justice issues impact on underrepresented scientists’ professional and personal communities.

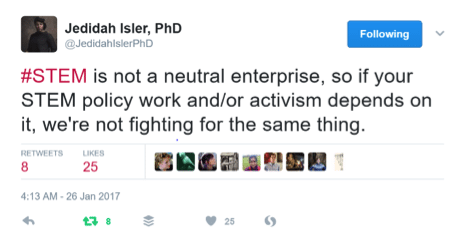

By January 26, practicing scientists had steadily expressed wariness. Astrophysicist and TED Fellow, Dr Jedidah Isler, who founded VanguardSTEM, a web series featuring women of color scientists, said on Twitter: “STEM is not a neutral enterprise, so if your STEM policy work and/or activism depends on it, we’re not fighting for the same thing.”

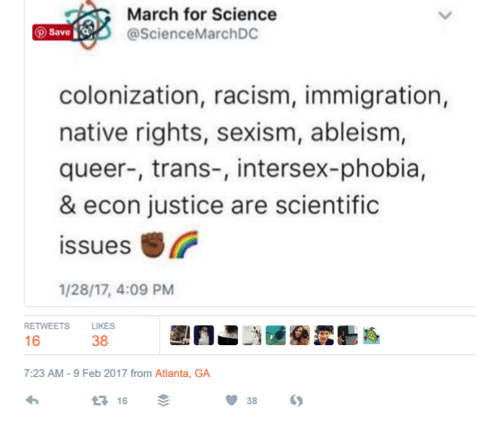

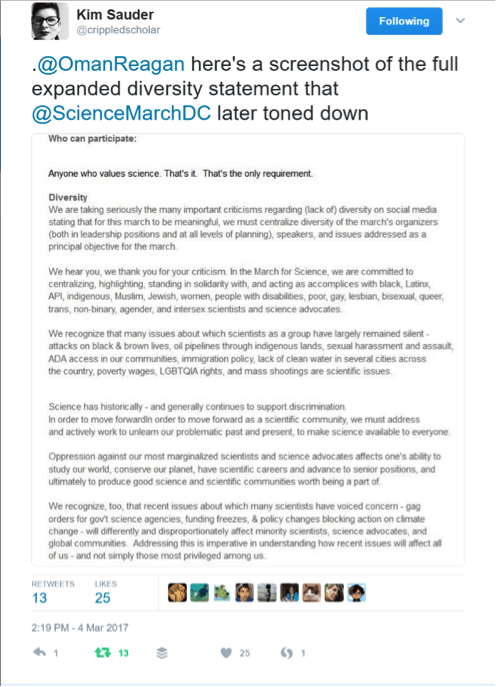

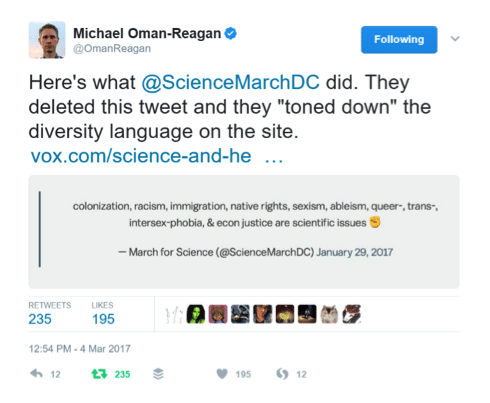

In a now-deleted tweet, and in response to this critique, the organizers said they had come to recognize that colonization and social justice issues were also scientific issues.

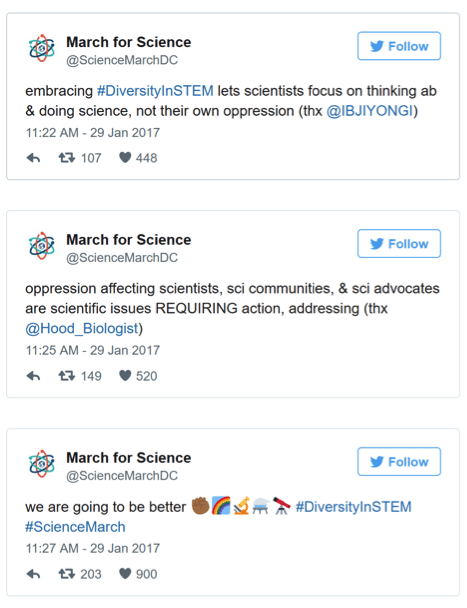

On January 29, MfS released its updated diversity statement and reaffirmed its commitment to inclusion on Twitter, by acknowledging the work of people of color in science who had shaped their stance.

Then There Was Pushback

The pushback to the diversity statement from the public came thick and fast at the same time as other high-profile scientists disavowed the idea of a science march. On January 30, Harvard University cognitive scientist Professor Steven Pinker said that a commitment to diversity “compromises its goals with anti-science PC/identity politics/hard-left rhetoric.” Over two million people interacted and responded to Professor Pinker’s tweet. Many scientists took a strong stance in solidarity of diversity. MfS was notably silent.

Th next day, the newly revised MfS diversity statement that strongly supported intersectionality was significantly watered down, much to the approval of Professor Pinker. The organizers then ignored the growing dialogue about how to enhance diversity in the march.

The constant flip-flops on its diversity stance suggest that, at best, the organizers are undecided or lack the skills on how to manage inclusion issues. At worst, it gives the unfortunate impression that they have a wavering commitment to diversity, one which bends to the shifts of public pressure.

The organizers continued to provide little detail about how issues of equity, access and inclusion will be addressed through MfS even when they talk about diversity. Many scientists, myself included, have enquired about the diversity team’s formal training and expertise in diversity and intersectionality. The diversity team has quietly gone through some changes. Notably its diversity lead has changed in recent days, with no public communication about whether members quit or were removed.

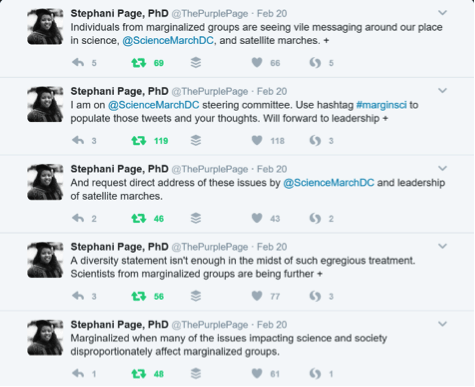

Dr Stephani Page, who is part of the Steering Committee, has led the discussions about diversity using the hashtag #MarginSci.

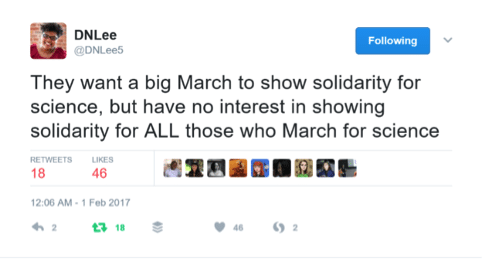

By long maintaining the idea that science and the march are not political, the organizers send a message to underrepresented scientists that the discrimination they face in science is not of concern. It signals that the organizers cannot see the connection between science policies, other restrictive social policy decisions and their effects on the life chances of marginalized researchers. Minority scientists cannot disentangle the impact of science policies from their careers and personal lives.

Ongoing Controversies

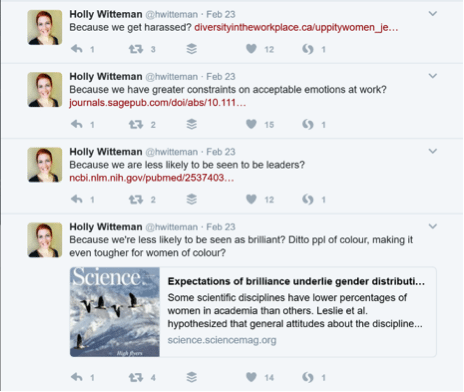

On February 2, in a now-deleted tweet, MfS chose to celebrate Introduce a Girl to Engineering Day by asking “ladies” to explain the gender pay gap. Scientists were critical of this approach, especially because the reasons for gender inequity are well documented. Given their international platform, MfS might have taken this opportunity to educate its followers using existing scientific studies on structural barriers to gender equity. Instead, the organizers chose to ask individual women to explain inequality to the very group that aims to represent science at a global protest.

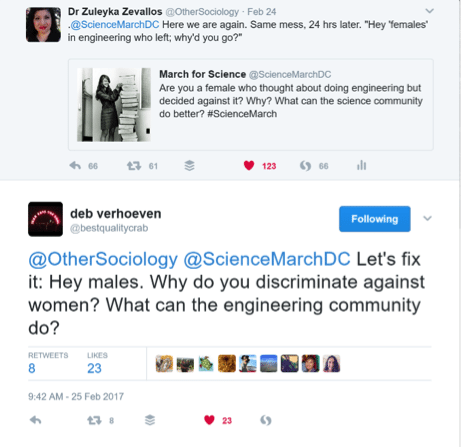

Despite heavy criticism, less than 24 hours later, MfS asked “females” to share why they left engineering. Once again, scientists were fed up with the approach, which reduces institutional issues to mere individual choices, rather than addressing the impact of sexism, racism, homophobia, transphobia and ableism (discrimination against people with disabilities) on minorities and White women in science.

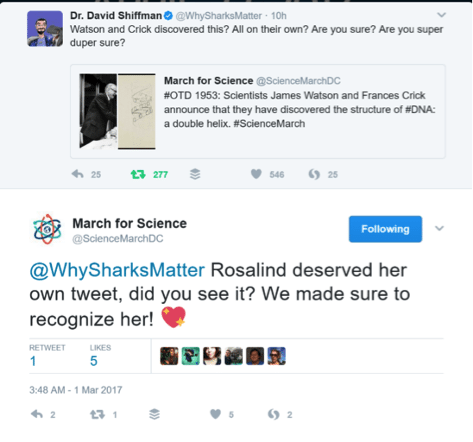

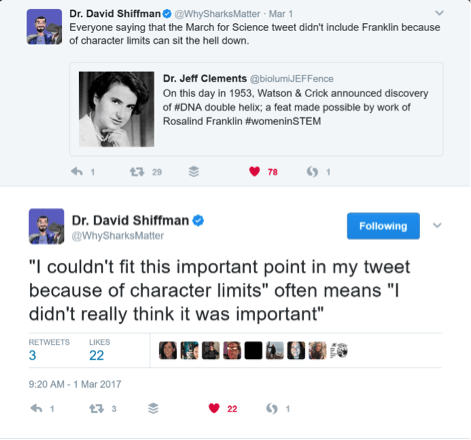

One week later, in yet another misstep, a series of tweets from MfS reinforced the exclusion of women in science. By tweeting in celebration of Professors James Watson and Frances Crick as the “discoverers of DNA,” MfS not only erased their well-chronicled thievery of Dr Rosalind Franklin’s research, but additionally, in their previous tweet about Franklin, MfS linked to an article claiming the theft of Franklin’s work was a myth. Scientists critiqued both the misleading article and scientific oversight. Hundreds of scientists, predominantly women, tweeted their justified disbelief that MfS would reproduce one of the most infamous cases of sexism in science. The only response MfS gave was to a male scientist, Dr David Shiffman. Dr Shiffman noted this gender imbalance and wasn’t buying their excuse.

The MfS central committee’s reticence to make a strong commitment to diversity only emboldens other satellite marches to devalue the input of underrepresented scientists.

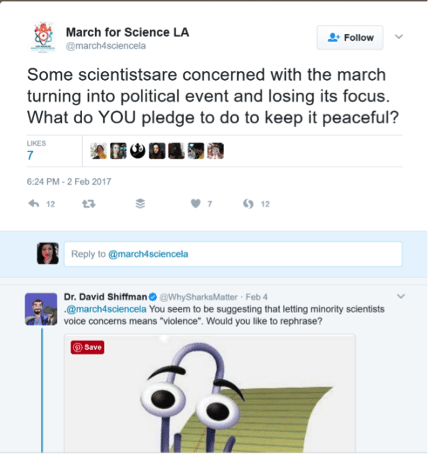

Following widespread push-back to diversity (so-called “identity politics”), most vocally by White male supporters, March for Science Los Angeles engaged in dog-whistling in early February, by suggesting that making the march “political” might lead to violence. While some scientists questioned this logic at the time, the tweet resurfaced again in early March. When questioned about it, the Los Angeles team deleted the tweet, leading to broader discussions amongst scientists about conflating minorities with violence and the racist discourses that falsely equate a peaceful protest with Whiteness.

Slow Response

Even when members of the MfS team concede mismanagement of diversity issues, they still effectively separate science and political engagement. Science communicator and MfS Steering Committee member Lucky Tran, who is an Australia-raised refugee born in Kuala Lumpur, says: “The team isn’t a monolith and there are lot of people in it, some new to movements… In my lifetime, I’ve not seen scientists be so willing to come out in to the street.” This is not true to people of color scientists who have worked tirelessly in social movements most of their lives, including lobbying to have Black Lives Matter recognized in academia. This is the reality for women who have worked to expose sexual harassment in science. This is not the case for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex or asexual (LGBTQIA) scientists who march for Pride. This does not reflect the professional efforts of disabled academics working to ensure protests are more accessible.

Apart from three women scientists who have been personally responding to the public critique, MfS as an organization continues to lag on promoting diversity publicly. My review of the early MfS social media posts shows that, of its first 1,500 tweets, there had only been 14 posts that directly address the diversity plans for the march. In the same time period, only two of the first 78 Facebook posts directly addressed diversity. Where diversity was discussed, the posts are largely apologetic in response to critiques from scientists.

Looking at other early social media that address other themes of diversity, around a dozen posts on Twitter and two posts on Facebook speak to social justice issues (such as the visa and immigration ban). Another 50-odd posts celebrate women in science, through the #ActualLivingScientist tag, a social media campaign to promote public awareness of working researchers, and in recognition of International Day of Women and Girls in Science.

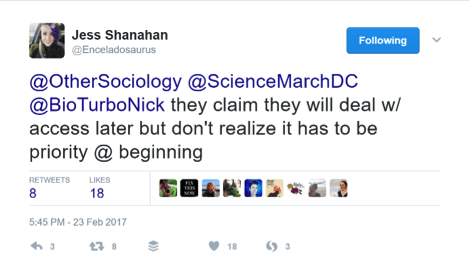

A focus on women scientists is great, but this represents a minuscule number of the MfS public communications. Plus, there are notable gaps, particularly with no recognition of LGBTQIA scientists. More broadly, the organizers have repeatedly ignored disabled and queer women who have volunteered to improve accessibility and inclusion. One disabled woman researcher was abused by MfS supporters for raising this issue, while others have been told by the organizers that the team is not ready to think about disability. Accessibility requirements cannot be added later; this issue must be planned from inception. It requires leadership from disabled experts.

My analysis of MfS’s early social media also shows that in the first two weeks of Black History Month, MfS tweeted only twice about this significant cultural event. In the same period, there were no Facebook posts in commemoration of Black history. By contrast, on February 6, MfS published 12 tweets about SuperbOWL (a celebration of owl facts on Superbowl Sunday), and 23 tweets on Darwin Day. Darwin is an important scientist; but if MfS can find the time to highlight his achievements, as well as elevate the study of owls, surely they can do more to focus on other scientists who are not White, heterosexual, cisgender, able-bodied men. Diversity does not have to be a zero-sum game: there is room to celebrate scientists from various backgrounds.

Yet that’s the sticking point: Darwin can be celebrated over and over without this being “political” not simply because of his tremendous contributions to science, but specifically because he is the unquestioned embodiment of “science.” Darwin’s story is recognized and remembered because he is the taken-for-granted norm: he is a White, cisgender, able-bodied heterosexual man of Christian background. Darwin’s intersecting identities (his race, gender, able-bodied status, sexuality and religion) are not seen as “identity politics,” even though these characteristics enabled his education and career success. Everyone else who does not fall into this “norm” is being “political” for wanting their rights addressed alongside the very policies that impact on their careers.

On March 10, March for Science released yet another revised diversity statement. It is thoughtful, which is encouraging; however, it is also their fourth revision. It has only come about because underrepresented scientists, especially women of color, continued to provide expert advice and constructive critique, at great cost, against an onslaught of online abuse and professional pressure. It is only now, after close to two months amassing a huge social media following, that the organizers have released an anti-harassment policy. Minority scholars kept pushing for this, to protect colleagues from the barrels of hatred deployed anytime an underrepresented scientist speaks up about racism in the March for Science communities. Progress has been too slow and the unpaid labour to make it this far has added to the pressure faced by scientists who are already marginalized.

At the time of writing, no concrete plans have been released as to what specific goals the new diversity statement is working towards and no there are no details about how the organizers are integrating the leadership of equity and diversity experts from minority backgrounds. We do not know what specific advice the march organizers draw from professional bodies representing minorities in science.

Diversity is not just a buzzword: it requires scholarship, practice and activism. It is focused on specific social justice outcomes. Diversity can only add value when leaders take seriously the responsibility of equity, inclusion and accessibility.

Why Diversity Matters

Discussions over the march are important not just due to the planned demonstration. The debates matter because they reflect broader issues of diversity in science.

Science has been used to reinforce social inequalities, from slavery and other forms of racism to genocide by the Nazi regime. Science also recreates present-day inequalities. While women make up half of all undergraduate students in science and engineering, they represent only one third (28%) of senior researchers, and 3% of Nobel Prize laureates. This is an outcome of the Matilda Effect, the systematic repression of women’s contribution in research.

Beyond gender, the lack of diversity in science is what happens when we ignore access and inclusion. From negative stereotypes; to teacher biases of racial minorities; to being devalued; to inadequate career support; to a lack of science mentors, science careers further marginalize underrepresented groups. Indigenous scientists face additional barriers, despite their high aptitude for science.

Black, Latin and Asian women are doubly impacted by gender and racial inequality in science careers. LGBTQ researchers face high levels of workplace harassment, especially women. Minority scientists with disabilities face multiple misconceptions about their physical and mental abilities. These co-occurring experiences of inequality affect the daily work and recognition of underrepresented scientists.

Through poor communication of diversity planning, as well as by omission, MfS is replicating problems of diversity. In doing so, it misses out on the benefits of diverse minds, which would otherwise lead to higher productivity and success.

Science IS Political

The reticence to undertake an informed commitment to diversity is baffling, given the extensive expertise the organizers might draw on. Dr Isler suggests one model might be Inclusive Astronomy, a program that outlined some general principles and resources for inclusive leadership in diversity events. At a minimum, this means working with experts who understand the data-driven issues and solutions to diversity, and collaborating with stakeholders, such as peak professional organizations, as well as knowledge-brokers, such as experts on intersectionality. Moreover, there are lessons on the successes and critiques of intersectionality from the Women’s March, which include robust discussions on how to make protests more accessible for disabled people, and more inclusive of transgender people, people of color, and those who belong to multiple marginalized groups.

Reflecting on the Trump Administration, astrophysicist Dr Chanda Prescod-Weinstein, astronomer Professor Sarah Tuttle, and cancer biologist Dr Joseph Osmundson have detailed why scientists have “a moral duty” to act in resistance against fascist governments. From rebelling against the Nazi regime to collaborating with civil rights activists, they argue: “There is a proud tradition of the revolutionary scientist.”

An international movement to protest poor science policy decisions must honor this tradition, to redress the damages that science contributes towards marginalized communities, as well to reflect the diversity of science practitioners. This means supporting the human rights of scientists, rather than pretending that one can separate scientists from science. This means recognizing and clearly addressing the systemic barriers that exclude underrepresented groups, rather than pandering to notions that science is produced in a political vacuum.

I want March for Science to be a success. Its mission “to champion robustly funded and publicly communicated” is noble, as are its other goals, which include the promotion of “evidence-based policy and regulations in the public interest.” I am a first-generation Latina migrant from a poor working class background and the first person in my immediate family to complete a university degree. My work and family life have been shaped by violence, sexual assault, workplace sexual harassment and racial discrimination. I know only too intimately what it is like to have teachers, colleagues and managers actively discourage me from pursuing my goals, whilst managing multiple structural barriers every step of my career. I have dedicated my life’s research to social inclusion, and I have volunteered for over a decade to improve equity in academia and beyond. Yet this is nothing unique: like many other researchers from minority backgrounds, I see and respond to the myriad of ways in which science is political. Underrepresented scientists have been fighting for diversity as part of our survival, with many other colleagues paying a much higher price for their professional endeavors and activism.

From its history, to its contribution to the oppression of minority groups, to issues of inequity that tip the scale against the success of minorities and White women, it is important to keep pushing the march organizers to proactively represent the full rubric of humanity that is engaged with the pursuit of science. Diversity is invaluable to scientific innovation. Any march for science needs to own and address the politics of science, and be prepared to lead us into a more inclusive future, rather than retracing the missteps of the past.

***

Dr Zuleyka Zevallos is a Latin-Australian sociologist and Adjunct Research Fellow with Swinburne University. Zuleyka is an applied researcher who has run several state and national research programs and policy initiatives. This includes developing and managing the first national equity and diversity program in Australia for science, technology, engineering, mathematics and medicine. Zuleyka writes extensively on social justice issues on The Other Sociologist. Connect with her on Twitter @OtherSociology.