By Omaya Sosa Pascual y Jeniffer Wiscovitch | Center for Investigative Journalism

English Version by Julio Ricardo Varela | Latino USA

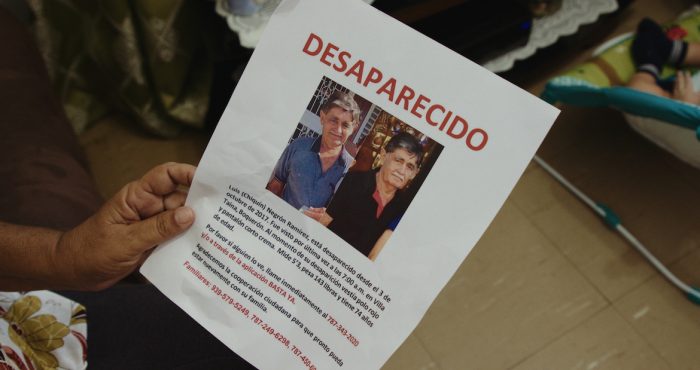

Missing persons document for Luis Negrón Ramírez, missing since in Puerto Rico since October 3, 2017 (Photo by Leandro Fabrizi Ríos | Center for Investigative Journalism)

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO — Anyone passing through the main streets of Puerto Rico’s metropolitan areas has seen them: homemade signs that carry sadness, with photos of missing persons after Hurricane María and the contact information of the relatives who are still searching to find them.

Nonetheless, close to three months since the storm, 45 people are still listed as missing, and efforts by Puerto Rico’s police to locate them have been minimal or almost non-existent, according to new reporting by the Center for Investigative Journalism (CPI) that involved a review of documents, interviews with law enforcement officials and relatives of the missing.

Although police issued a “special plan” to deal with the avalanche of cases after the hurricane, this occurred three weeks after the storm. As a result, police couldn’t take advantage of the early critical time period to start searching for missing persons.

In an interview with the CPI, Puerto Rico Police Commissioner Michelle Hernández de Fraley attributed the delay to the serious conditions caused by María, which led to major communications issues and stretched resources that had to be dedicated to immediate rescue work.

As she explained, information about missing persons started to manually trickle in. The reports were assigned to lieutenant colonels. When police discovered an unusual increase in missing persons reports, a meeting was scheduled on Saturday October 7 to examine and prioritize the cases dated between September 20 and 27.

Even though Puerto Rico was still in a state of emergency by the time of the October 7 meeting, police decided to concentrate internally on the earlier cases because of the following reasons, according to Hernández de Fraley: there was no access to transportation and only one media outlet was broadcasting on air, so relatives’ desperation was elevated.

“Many of us in the Puerto Rico Police were experiencing communications problems. For most of that time, police had to travel from our sectors to central headquarters and report,” the commissioner explained, when the CPI questioned her about the police’s delay in beginning to work on missing persons cases after the hurricane.

The “work plan” to deal with these cases, the commissioner noted, was a verbal instruction given to the members of the Criminal Investigations Unit (CIC), the leadership of the Missing Persons Division and all police commanders. Coronel Francisco Rodríguez, the CIC’s Auxiliary Commissioner, gave the verbal order.

The “plan” said that investigators had to visit the missing persons’ homes to see if they had returned and to also conduct more targeted searches, according to Sergeant José Carlo Rosario, the head of the Missing Persons Division. However, based on several interviews, agents just called or visited shelters and hospitals in their respective areas. They also called and visited the Institute of Forensic Sciences (ICF).

“The process hasn’t changed at all. Everything continues as is. What has changed is that the people, the citizens, have gotten more desperate,” Rosario told the CPI. He also said that more resources to prioritize missing persons cases were assigned to the police sectors.

The CPI found that the resources assigned by police for this task were scarce. For example, in the Aibonito Sector, one agent was assigned to 19 missing persons cases across five mountain towns. Two agents took on 19 cases across nine towns in the Mayagüez Sector. Many of the initial missing persons eventually appeared on their own once communications improved. However, five of the missing persons were found dead.

The search to find missing persons has rested mostly on the hands of family members, who do their best with limited resources to conduct daily searches.

The Case of Luis “Chiquín” Negrón Ramírez

The CPI found cases where not even minimum steps were taken. Among those is the case of Luis “Chiquín” Negrón Ramírez, who disappeared on October 3 after leaving his house early in the morning in Cabo Rojo’s Villa Taína area.

Negrón Ramírez, a 74-year-old carpenter, was in good health and in good spirits, but before the hurricane, he had begun to forget things—an early sign of possible dementia. He had medical orders to get tested the same week that Hurricane María hit Puerto Rico, his wife Ivette Andújar Torres told the CPI.

“Sadly [the police] have done nothing,” Andújar Torres said.

The hurricane severely affected the surroundings of the Negrón Ramírez home, as well those of family members. His son lost his roof, and one of his daughters had a newborn who required medication that could not be obtained.

Without no power or water, Negrón Ramírez’s family had to move to that daughter’s house to survive, making it difficult to care for his sister—his 80 year-old neighbor, who suffers from mental retardation.

Being unable to solve the multiple problems of his family and his own home, Negrón Ramírez fell into a depression. Every day, he feared seeing his wooden home and zinc roof get swept away by heavy winds.

“From then on, since the hurricane, who he was, changed,” Andújar Torres said, looking down.

Although his home never suffered the damage that he feared, Negrón Ramírez was sad and passed the days crying. On Friday September 29, eight days after Hurricane María, Negrón Ramírez walked around the house “with a look that just wasn’t the same” as before, his wife remembered.

“It was like he wasn’t inside himself. The look was one of being lost,” his 31-year-old daughter Denisse Negrón Andújar said.

The night before he went missing —Monday, October 2— Negrón Ramírez slept over at the home of his sister Sonia, who suffers from mental retardation and up to this day still doesn’t know that his brother (and caretaker) is missing. They have told her that he is visiting other relatives to avoid hurting her with the news, since she also has a heart condition.

Sonia told the rest of the family that his brother left her house at 7am and headed over to his house, which was next door. There, they believe he put on the red polo shirt and cream-colored shorts that his wife and daughter left on his bed. He used these clothes to work in, since on the previous day, he said he was going to clean his home, which still had some debris caused by the hurricane. But when his wife and daughter arrived at the house, he wasn’t there, and neither was the clothing.

It was the last they heard about their Chiquín.

Two months since he’s been missing, Ivette and her daughters are completely dissatisfied with the police and their work. According to them, and contrary to the orders from Col. Rodríguez, not one police officer has visited their home. Instead, they are the ones who call the police when they get a call from someone who says they have seen Negrón Ramírez in some place. They are also the ones who have verify if the call is about Negrón Ramírez or not. They also do not get calls from the police to discuss about leads in the case.

“All they say is that they are searching,” Denisse said.

The Investigator

At the moment, the case’s investigator is Sergeant Joel Ayala of the Mayagüez Sector’s Criminals Investigations Unit. Currently, Ayala has a workload of three missing persons cases, including the Negrón Ramírez case.

Approached by the CPI to obtain his version of the story, Ayala appeared reluctant and nervous, but he rejected that police are not making an effort to find Negrón Ramírez. He did, however, acknowledge to the CPI that he only returns phone calls to relatives when they call him.

“Obviously, if I don’t have information, [I don’t call them]. I explain to them what is happening with the investigation. This information got corroborated, anything, you call me. They are posting on Facebook, saying that any information out there, to please have people communicate with me. Obviously, the information gets to them and they pass it on to me,” the sergeant said.

Two-and-a-half months into the case, the police have yet to activate the Search and Rescue Unit, which specializes in finding people lost in wooded areas or in places difficult to access—such as in front of the Negrón Ramírez home. That area has large vacant lots, places with thick trees, the Pirata Cofresí Cave, as well as large coastal and land areas.

“I will take care of that next. Since there have been certain communications problems after Hurricane María, we haven’t been able to follow emergency management protocol,” Ayala said two months after Negrón Ramírez was reported missing. Nonetheless, he did say he couldn’t tell exactly when he would begin this process.

According to Negrón Ramírez’s daughters, even with their limited resources, Cabo Rojo’s Emergency Management team and some civilian rescue groups searched for Negrón Ramírez in the area, but Sgt. Ayala said he didn’t have any knowledge of this effort and that he found out about it through the CPI.

Ayala emphasized that he has visited area hospitals and several mental health centers. He also contacted the Traffic Division to see if there has been an accident with any unidentified pedestrian. In addition, Ayala noted he worked with Forensic Sciences in Mayagüez to verify through photos if Negrón Ramírez is dead and has yet to be identified. Ayala said that he has not taken steps to visit hospitals outside the island’s western area, nor has he driven to the main headquarters of the Institute of Forensic Sciences in San Juan.

A resident in Aibonito, Puerto Rico, lets people know where he living now. (Photo by Leandro Fabrizi Ríos | Center for Investigative Journalism)

When asked why police have not sent a specialized search and rescue unit, Commissioner Hernández de Fraley acknowledged that the delay in starting efforts after María made the unit’s work ineffective.

“A rescue unit usually responds right after something happens and focuses on one specific area. If several weeks have already passed, there are some things that are just not practical,” she said.

After conducting a police database analysis of the 45 missing persons reports still active after the hurricane, the CPI noted a pattern of cases with adults, especially older adults, who had perceptual difficulties or mental conditions. Interviews with family members, neighbors, police officers, rescue works and funeral directors about four cases in Cabo Rojo, Carolina, Aibonito and Yauco asked about the methodology used to find missing persons. All the interviews revealed that the missing persons in these cases became disoriented or unbalanced with the changes that the disaster brought to their surroundings.

Three of the four cases also saw little action from a police force without resources. According to Sgt. Rosario of the Missing Persons Division, there are two agents assigned to missing persons cases in each of the 13 commands, but the CPI found that the Arecibo Sector had only one agent, who was also tasked with administrative work.

The Case of Nelson Jonathan Martínez Rivera

The same day Negrón Ramírez went missing in Cabo Rojo, on the other side of the island in Carolina, 28-year-old Nelson Jonathan Martínez Rivera also went missing. The young man, who has autism, left his home on his regular walk, but his family believes that María’s devastation around his familiar surroundings disoriented him, and he got lost on the walk back to where he lived.

Since then, his family, headed up by his uncle Hilton Martínez, have not stopped looking for Martínez Rivera, posting signs and banners almost everywhere in various cities and on social networks with a cell phone number that rings daily with clues from people who say they have seen Nelson. The relatives and the 500 people who are helping them are the ones leading the search. Martínez thinks the police do have the resources to conduct the search.

Nelson’s uncle is a middle-aged military man who handles emergency management in a hospital. He said that he is putting his experience to use as he searches for his nephew.

“Whatever you think we have done, we have done it. I have personally gone and spoken to every health and law enforcement official in the Puerto Rican government. I went to each of the shelters. I have visited all the hospitals. I’ve gone to all the media outlets. I’ve been on television programs. I’ve done a couple of Facebook Live videos. Then we decided to go to a printer and print eight hundred flyers. And then we created bigger signs and banners to put on Puerto Rico’s main highways,” he said.

According to him, the process has been devastating for the relatives of missing persons. They live each day with the anguish of not knowing whether their relative is alive or has food, water or a roof over their head. He also noted that it must be more difficult for those families who don’t have the knowledge or the resources to conduct a search like the one his family is conducting.

Martínez explained that the police’s biggest failure was the long delay it took in starting searches, when time is of the essence. In the case of his nephew, the police told him to wait 72 hours before filing a report, when in fact this was unnecessary and only led to lost time in the search. Then, he said, the police waited another week to start field work.

He added that the police’s requisition order ignored one critical fact: his nephew’s mental condition.

His biggest problem, however, was with the police in San Juan. When Martínez when to the main headquarters to ask if police would distribute flyers to other police stations in the capital city, they told him they could not and that he himself had to go to each one and deliver them individually.

Given Martínez’s emergency response and health care experience, the CPI asked him if he thought other people with mental conditions were also disoriented and got lost because of the hurricane.

“I don’t think so. I know so, because that it the case and that is the truth,” he answered.

Martínez said that as part of his family’s searches, they have spoken with more than 500 people and found out that families faced similar problems with autistic children and people with Alzheimer’s.

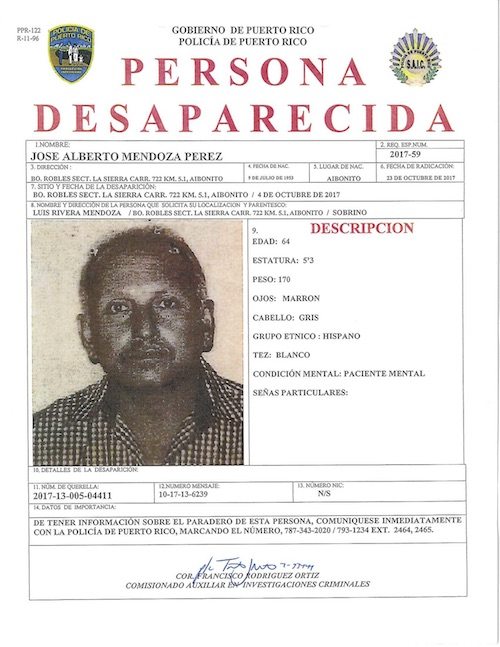

The Case of José Alberto Mendoza Pérez

Missing persons document for José Alberto Mendoza Pérez

Another case is that of José Alberto Mendoza Pérez. On October 4, Mendoza Pérez went missing in Aibonito after going out for a walk on his street. The man, who was a mental patient, was affected after María destroyed his house in the rural neighborhood of Robles.

Following the hurricane, after he moved with other relatives to his sister’s house in the same neighborhood, his behavior began to change. He shaved his head, and that day, he went out to walk in the same area where four generations of his family lived. The CPI contacted Mendoza Pérez’s relatives. They chose to not make statements, but people nearby indicated that some of the relatives were unhappy with the police because they never looked for Mendoza Pérez in the huge mountain right in front of his house and his sister’s house—even though relatives told police that José Alberto could be there.

Ángel Ocasio, the agent from the Aibonito Sector, was in charge of this investigation. He knew the case well because he was in constant contact with neighbors and relatives, he confirmed. Ocasio, who investigates missing persons in five mountain towns, acknowledged in an interview that after the hurricane, he was unable to investigate all the cases that came late from the sector command. He indicated that before the disaster, he took on three to four cases per month. In mid-October, he suddenly was assigned to about 20 cases.

Although Ocasio was finding that most of the missing people were appearing when communications improved, it was close to a month after the hurricane when the Mendoza Pérez case came to him. Ocasio said the missing person’s nephew visited his office to see what had been done with his uncle’s case, and the agent said he had not yet been able to attend to that case. He explained that the family believed that because of Mendoza Pérez’s mental health history and the behavior he began exhibiting after the hurricane, the man could have become disoriented.

The case has yet to be solved.

But close to two months later, the owner of some goats was following his animals’ trail at the mountain in front of the Mendoza Pérez home when he found a corpse in an advanced state of decomposition.

The corpse seemed to match Mendoza Pérez’s description, according to Ocasio. However, the family will have to wait for the DNA results from the Institute of Forensic Sciences. If the identification is positive, they will be able to dispose of the remains. This could take more than a year, said Sergeant Carlos Rosa, director of Aibonito’s Homicide Division, although Karixia Ortiz, a spokeswoman for the Public Security Department, said that “it can take up to three months.”

The Case of Paulita Cidrón Rodríguez

An exception to the police delay was the case of Paulita Cidrón Rodríguez in Yauco, who went missing on October 2 and was found dead on October 3. In this case, the 69-year-old Cidrón Rodríguez, who has several physical and mental health conditions, left her house for the bank at 6:20am, according to her son, Steven Cintrón Cidrón. He believes his mother going missing and her subsequent death were caused by the hurricane’s devastation.

“There was no bridge, and she wanted to cross. But she had no access or someone to give her a ride. Or to find a way to get there. I believe that such things affected her. This hurricane left us with a total disaster. It has been really difficult to survive this,” he said.

The river in the area had flooded since Hurricane María, and the bridge that connected to her Diego Hernández neighborhood had fallen, so Cidrón Rodríguez could not use public transportation into town. Instead, she followed a path that neighbors told her about.

She never returned.

Eventually, one of the neighbors reported her story to the police. The police and emergency management took the same path, and the rescuers found the lifeless body of the woman. In the death certificate, the ICF listed diabetes mellitus as the cause of death. No mention is made of the circumstances caused by the hurricane.

“She had a small smile,” said her son, unable to control his tears, while he also thanked God that her mother’s body appeared and she had not been dragged by the river.

He said the prosecutor could not get to the body due to access problems that made it difficult for cars to travel in the area the days after the hurricane.

Cidrón Rodríguez has not been added to the government’s official count of deaths related to Hurricane María. Three months after the hurricane, the official count is still at 64, but demographic data from the same government reflects an increase of almost 1,000 deaths in Puerto Rico from September 20 to October 30, compared to the same period in 2016. Experts in public health and demography have estimated that this increase is significant, and that it must be investigated to see how it is related to the emergency.

Héctor Pesquera, the Secretary of Public Safety and the person appointed by Governor Ricardo Rosselló to account for deaths related to the hurricane, has said that he sees no reason to investigate the increase in deaths or to make an epidemiological study of the deaths related to the devastation of Hurricane Maria because “there is no epidemic” on the island.

A 200 Percent Increase

Missing persons reports, which are filed only after people have lost contact with their relatives and a case is assigned by police, increased 200 percent in Puerto Rico the first week after Hurricane María left the entire population without power or communications. According to the data provided by Sgt. Rosario, director of the Missing Persons Division, it is estimated that the average number of cases reported per week is 20 to 25 people. From September 19 to September 27, there were 71 missing persons reports.

Under normal circumstances, Rosario explained that many of the reports relate to minors who leave foster homes and to people with debts or problems with the law, while some people do not ever want to be found. However, according to the data of the reports filed since Hurricane Maria —which include a photo and information in a public document— there is a pattern of missing persons with mental disorders such as depression, schizophrenia, dementia, Alzheimer’s, mental retardation and autism.

The CPI asked Commissioner Hernández de Fraley if the profile of missing persons in Puerto Rico had changed with the increase in cases after the hurricane and if that profile shows a pattern of cases of adults with mental health conditions. She indicated that the police had not done this analysis and they would have to study each case. At the same time, she requested specific information about the cases investigated by the CPI to conduct pertinent investigation, rectify issues if necessary and help the relatives.

Dr. Marinilda Rivera Díaz, a social work researcher and professor at the University of Puerto Rico, collaborated with the Community Support Center on the Road to Recovery established by the Río Piedras campus on a four-week evaluation of the university community’s pressing needs after María. According to Rivera Díaz, one of the areas of greatest concern was mental health and addictions, which worsened due to the lack of availability of services and medications.

“People who were in treatment at the time of the hurricane began to be affected by the absence of medications to stabilize their conditions, as well as the closing of mental health service centers. What is striking is that these people claimed that they had never been told in their respective centers about how to proceed in the event of a crisis or emergency. Nobody communicated this during the preparations before the passage of this atmospheric event,” she said.

Others believed that they had enough medication for a few weeks, but once the state of emergency was extended, they began to experience psychiatric complications that they tried to minimize through doctors who, since they did not have access to the person’s health record and history, had difficulty in writing the correct prescriptions, Rivera Díaz added.

The chaos surrounding the transportation system also hindered access to treatment.

“The train and public buses, means commonly used by this population to move between services, were not operating. This caused people to arrive unbalanced at places,” she said.

As for older adults, Rivera Díaz also saw how people with some conditions came to the center disoriented and with memory problems, which in her opinion was possibly reflected in hundreds of support centers, shelters and community service organizations around Puerto Rico the days following the hurricane.

“We were not operating under normal parameters and the lack of flexible protocols in these cases of devastation was palpable, which led to a situation of greater vulnerability for the population,” Rivera Díaz said.

Read the Spanish version here.

***

This story was made possible by the Futuro Media Group as part of a collaboration supported by the Ford Foundation.