Man with flag in Washington, D.C., 1981 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

If we want to talk in any kind of meaningful way about Puerto Rico in 2019, we need to know its history. Our present is on a continuum with the past, and when we know where we came from, we can identify those forces that are at work now. Now more than ever when it comes to Puerto Rico, we need this kind of knowledge.

Hurricane María laid bare the general ignorance in the United States about the island, as well as the specific racist indifference and cruelties of neglect of those with political and economic power. The current exodus, with little hope of recovery on the horizon, let alone sovereignty, represents a slow-moving cataclysm for the people there. None of this happens in a vacuum, and so now more than ever we need to know what has led us to this point.

The history of Puerto Rico is one strand in the oppressive colonial History of the United States.

Gilberto Gerena Valetín, during 1964 school boycott in New York City, 1964 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

As my father, Frank Espada put it in the introduction to his magnum opus The Puerto Rican Diaspora:

We are part of a great, invisible and historic national tragedy, a moral catastrophe which some ascribe to abstract historical forces, thereby neatly ignoring the suffering and exonerating the guilty.

Thus the need, as this writer saw it, for this work. It is an attempt to give voice to those who must bear the brunt of the failed policies of a power-hungry, greedy elite; to the victims of faded dreams of the glories of empire; of the so-called “accidents of history,” a smokescreen for racism, petty ambition and incompetence; of the cynical travesty which makes us “citizens” fit to fight and die in disproportionate numbers in this country’s wars but not allowed to vote in federal elections if we happen to live on the island, a fine definition of “second class citizenship.” It is an attempt to document the victims’ pain, fears, disillusionment, anger, and sorrow. But also, and perhaps in the long run more important, it is an attempt to honor their defiance, courage and determination to endure, survive, and eventually to overcome.

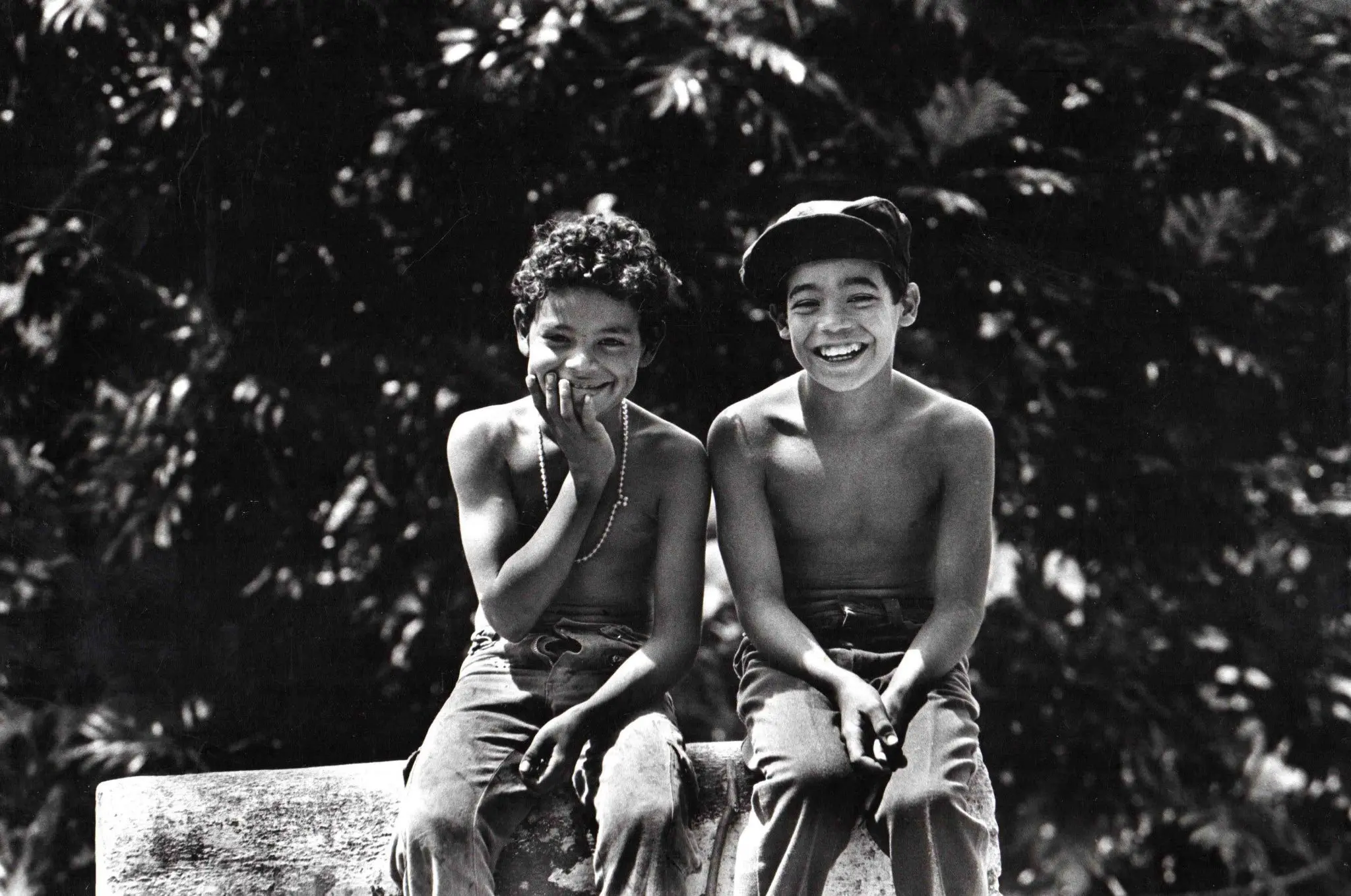

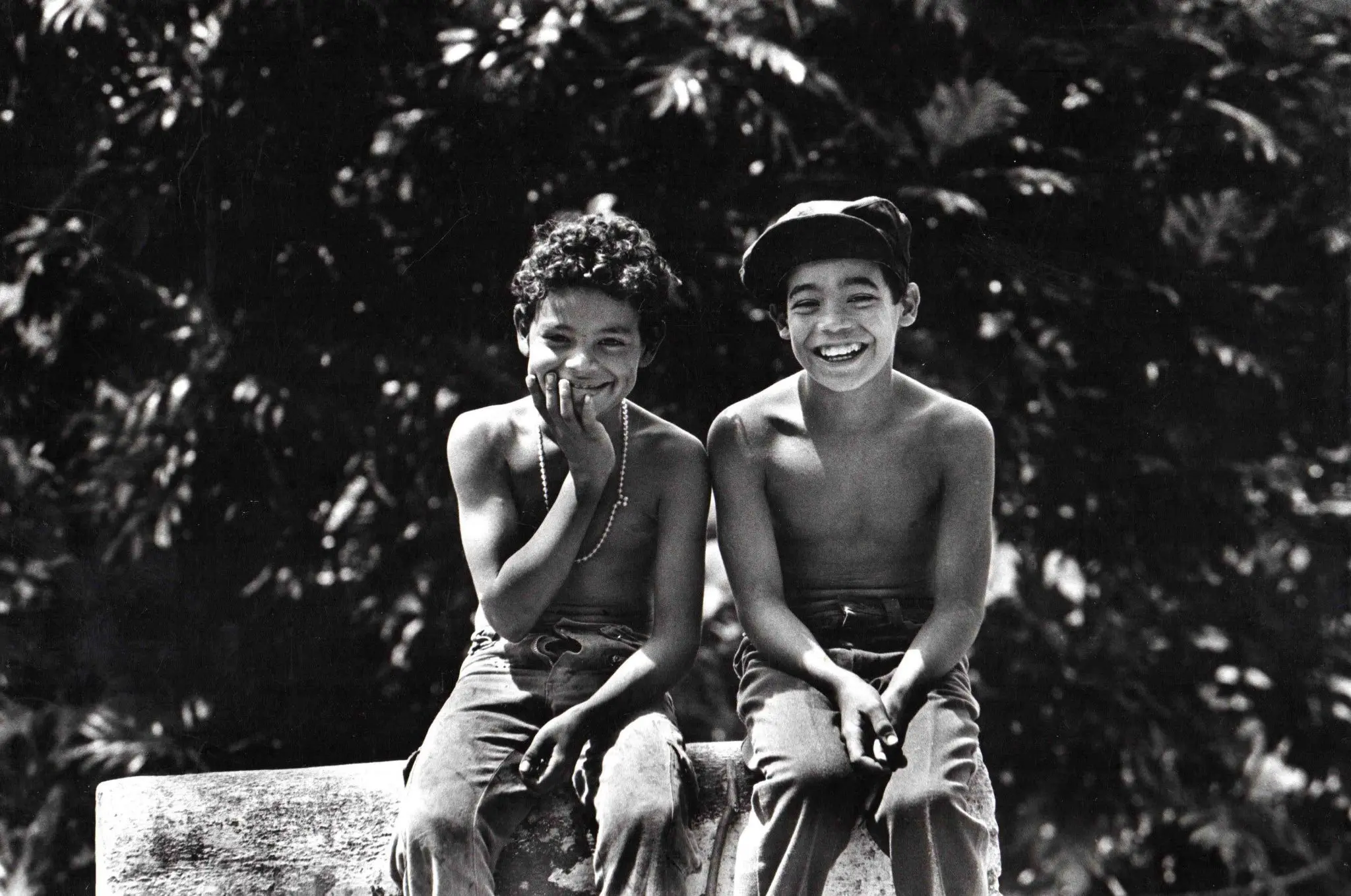

Daniel and Raphael, natives of the South Bronx Barrio la Pica, in Maunabo, Puerto Rico, 1981 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

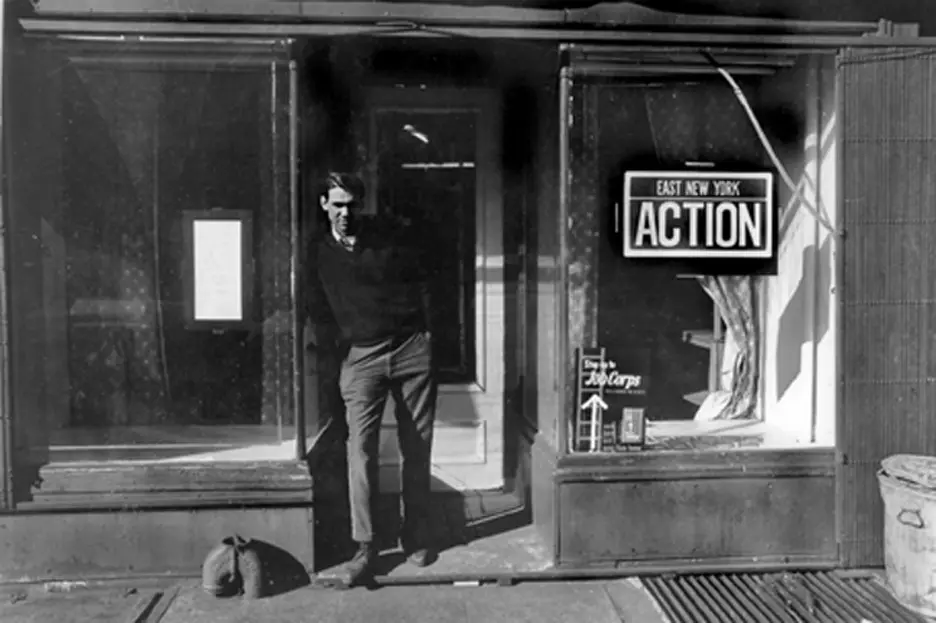

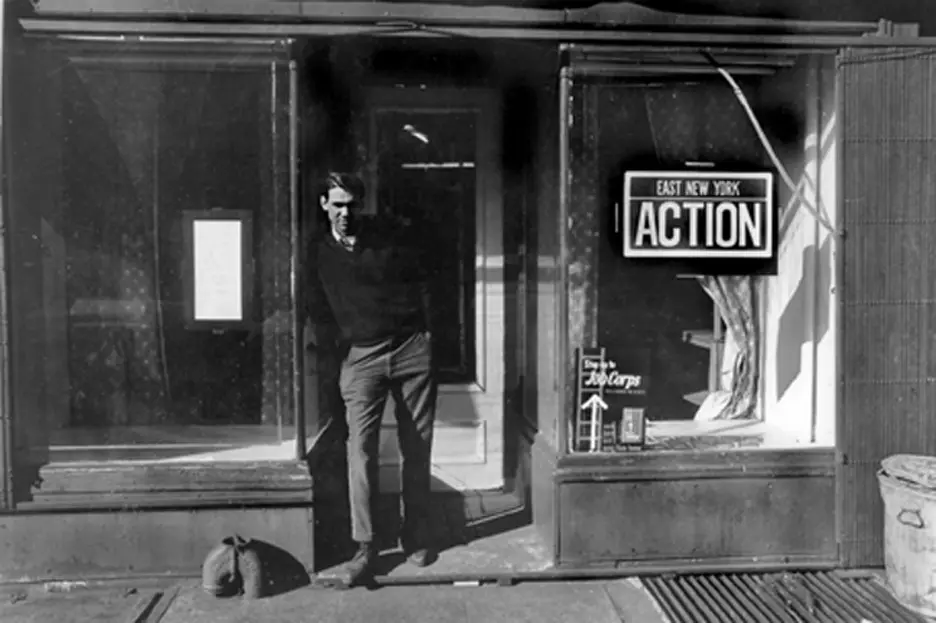

My father was 49 when he received a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities to document the Puerto Rican Diaspora. To that point, in many ways, he had lived the history he set out to record. He could say with Langston Hughes that America never was America to me.

Compared to other documentarians, my father had an agenda that he was upfront about, telling David González for his New York Times piece: “I was not pre-programmed by some know-nothing editor to bring back more proof as to the miserable lives we were living. It was to be as loving a document as I could produce.”

Lillian Jiménez expressed it this way: “As community activists we had to turn to visual imagery to capture the reality of our disenfranchisement in this society. We had to tell our own stories and honor our friends and families who were mischaracterized as depraved and as criminals. We had to visualize our humanity and our empowerment.”

Frank Espada, at East New York Action on Blake Avenue, New York City, 1963 (Photo courtesy of Jason Espada)

The project led him to unexpected discoveries, such as the presence of Puerto Ricans in Hawaii, Chicago, Lancaster, PA, and Hartford, CT—all elements of the larger story. All along the way he worked as an artist and advocate for these people, bringing together his skills as an organizer and all his strengths and talents.

He said: “The purpose of showing my work is to get young people thinking, to stimulate their minds and hearts, to make conditions known, and to attack injustices wherever they exist.”

The funding for the first phase of the documentary project took my father across the country, where he photographed and recorded interviews with more than 140 people from every level of society—artists and educators, fellow activists and working class people, gang members and clergy. He then traveled with an exhibit, titled “The Puerto Rican Diaspora,” through 1996.

- Christina, Barrio Tokio, Puerto Rico, 1984 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

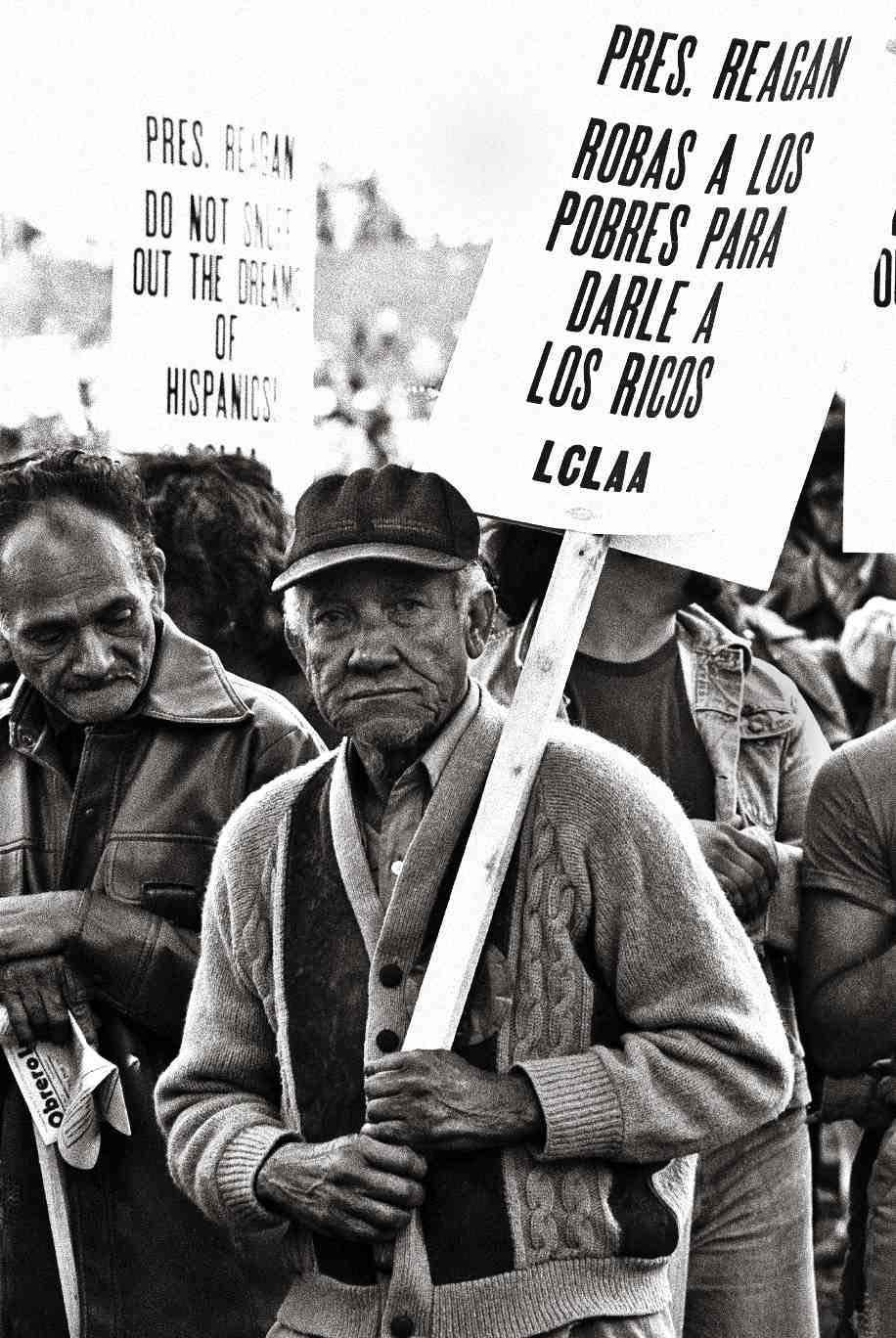

- Reagan”Reagan roba” solidarity demonstration, Washington, D.C., 1981 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

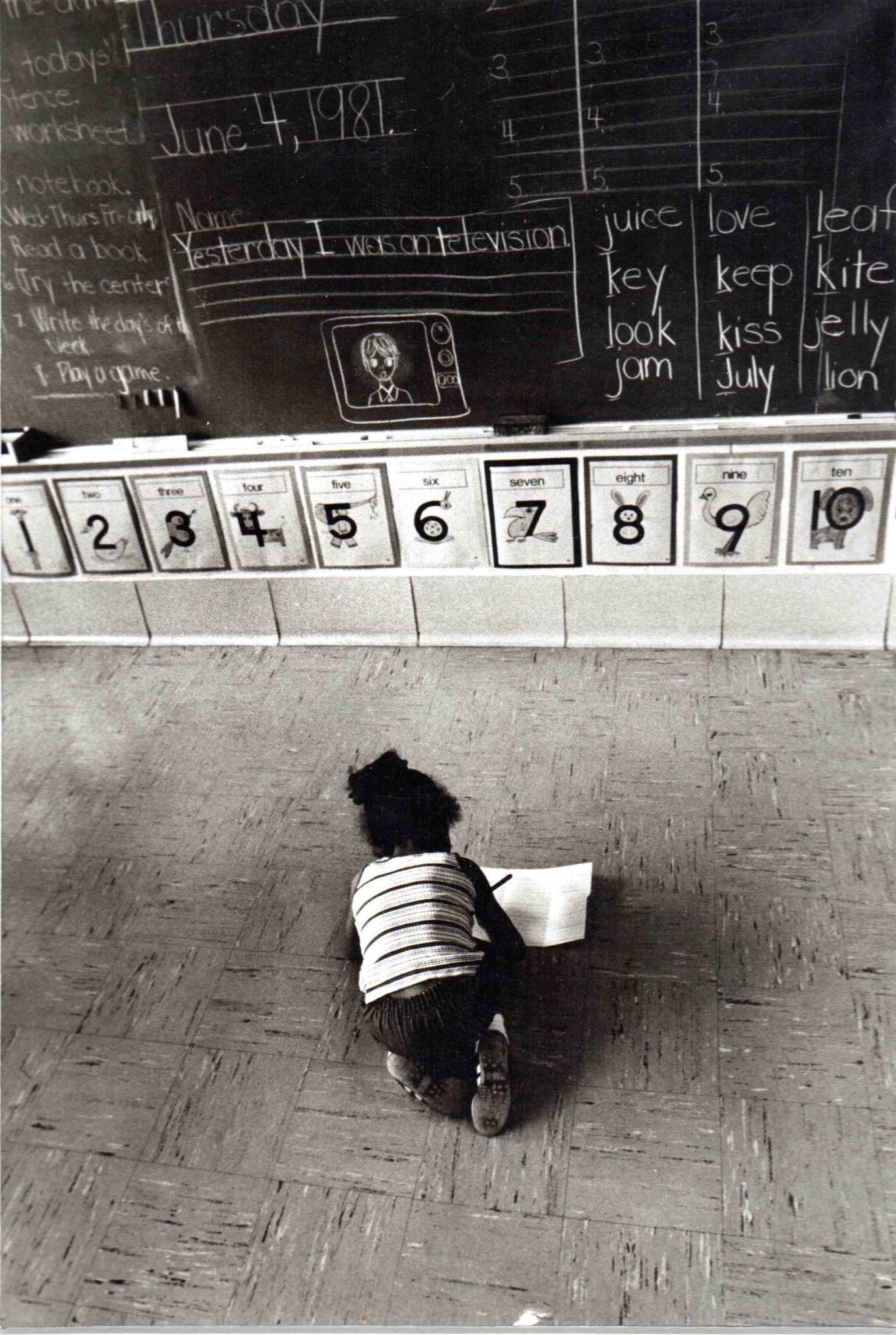

- Bilingual classroom, Reading, PA, 1981 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

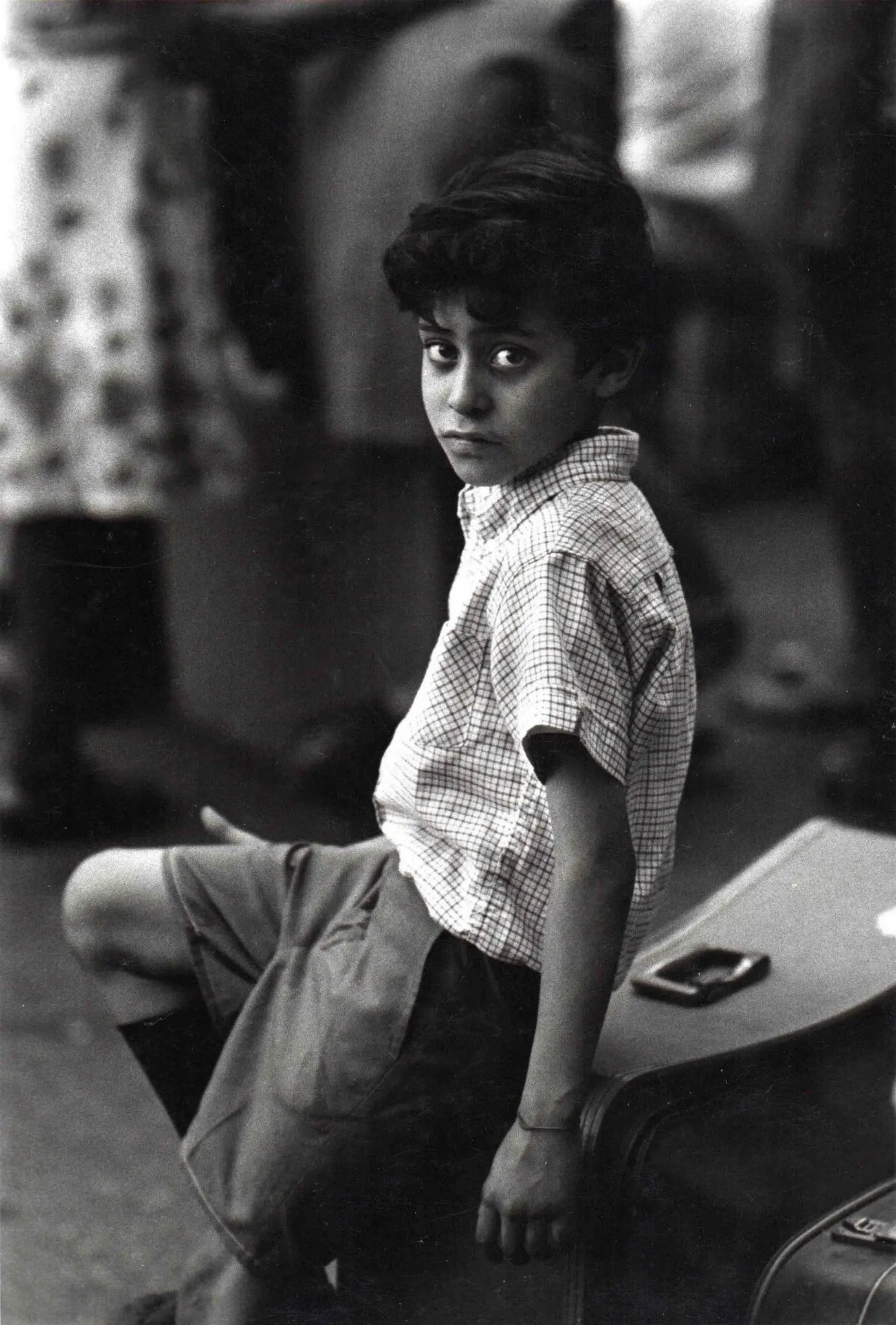

- Boy with suitcase going to Puerto Rico for the first time, New York City, 1972 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

Preparing his book a decade later —and 20 years after the Diaspora Project began— he would reflect on how little progress had been made for Puerto Ricans, and how in some cases what little gains were made were lost:

The first phase, the photographs and interviews, led me to other, more dynamic and unexpected possibilities. Being an activist and organizer most of my life, I concluded that this story could become a positive force in the struggle for justice and equity being waged in countless places by courageous, committed individuals. One constant stood out however: the third-class status, which has kept us at the very bottom of the socio-economic ladder for over a hundred years.

All indices of social pathology point in the direction of a stigmatized community, which has been marginalized, discriminated against, exploited and victimized. Our poverty rates between 1980 and 2000 have, if anything, worsened. From there follow all the attendant ills of an abused class: poor health, deficient schools, drug addiction, depression, and adolescent suicide. Puerto Rican children have by far the highest rate of lead poisoning, and suffer from the highest incidence of asthma of any group in the country. And they are often hungry—here in the United States of America, the richest nation in history. This is a powerful indictment of the system under which we live, where the top 1% own more than 90% of the wealth. And the gap between the “have mores” and the rest of us is widening daily…

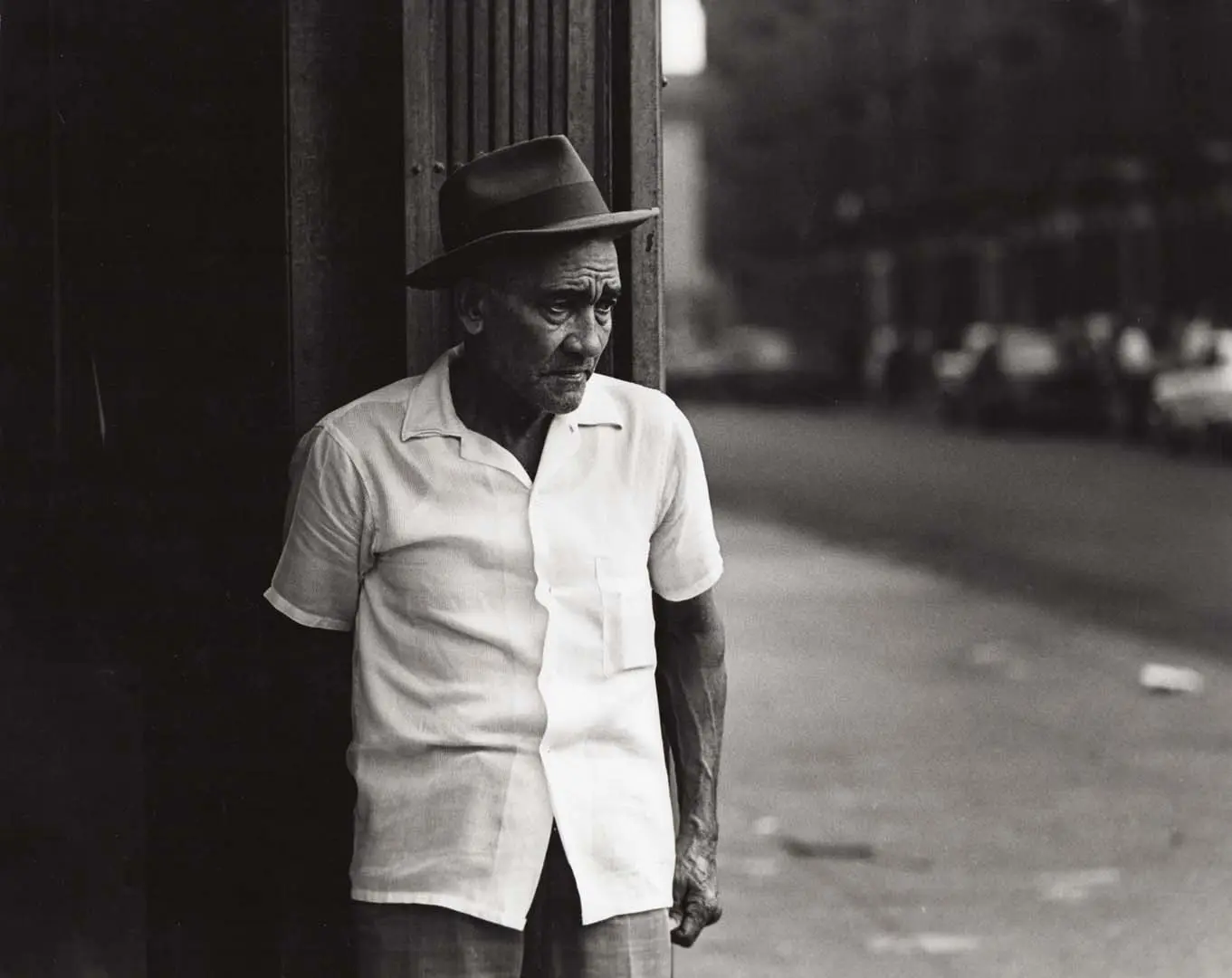

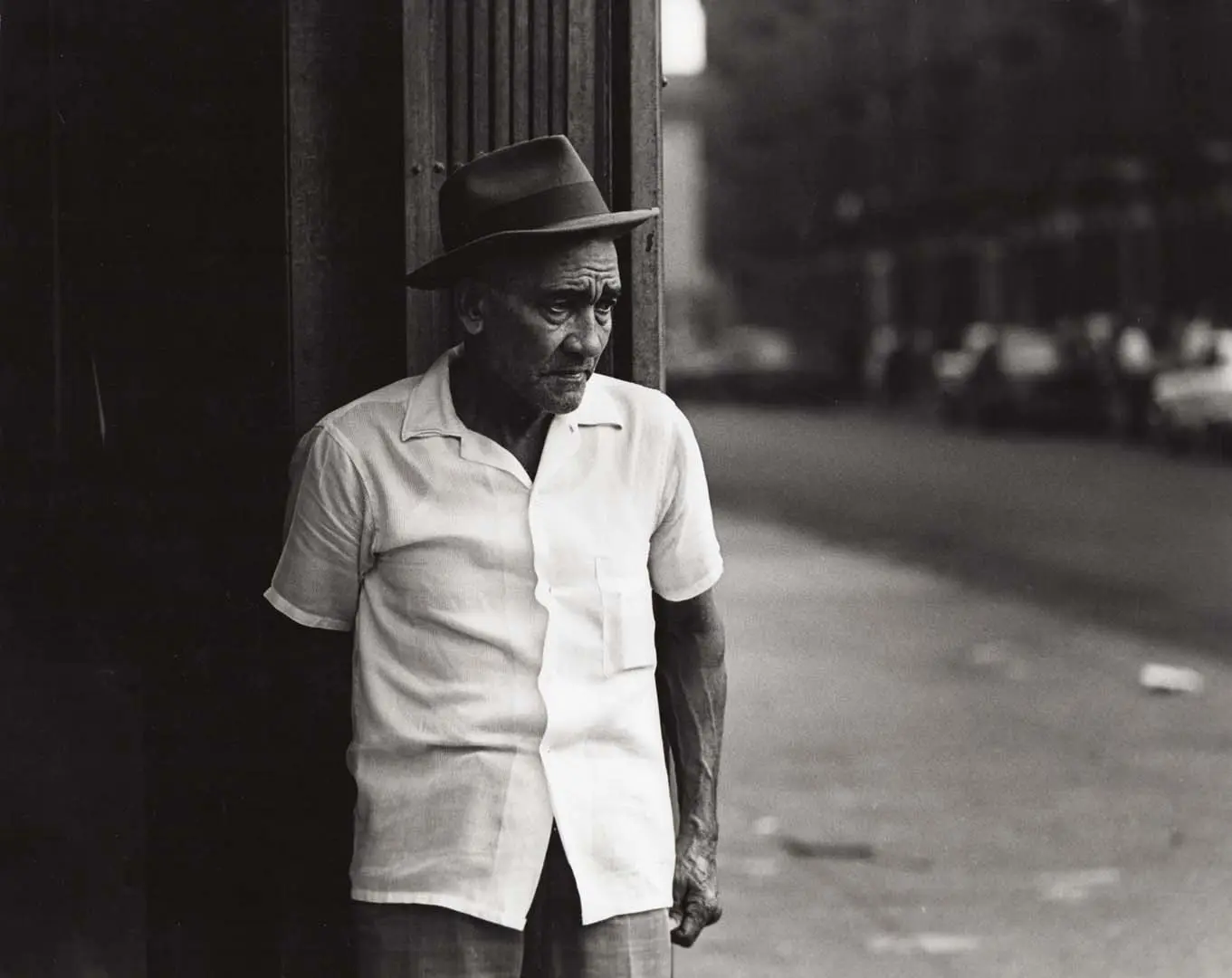

Man in doorway, New York City, 1965 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

And yet, his great heart found reason to go on working for justice:

In spite of this dismal outlook, I was encouraged by the spirit I found, defying the establishment, attempting to deal with the causes of our problems at their roots, refusing to accept the status quo. These compatriots are my heroes, I will always carry them in my heart…

Since my father’s passing in 2014, natural disasters have compounded the hardships faced by people on the island. We’re still under colonial rule there, with the complicity of the political class. As I put it in Reframing America’s Modern-Day Colonialism: Puerto Rico in Context in 2017: “Now that Hurricane Maria has destroyed what was already an extremely poor infrastructure, the vulture capitalists are circling. Not having caused enough damage, they are now brazenly angling to take over what little remains of the public assets.”

‘delirious they rampage,

with their dead eyes,

and insatiable hunger…’

The hundreds of thousands who have come to the mainland since María, compared to previous times, have less hope of return. For now, and for the foreseeable future, they are a dispossessed people.

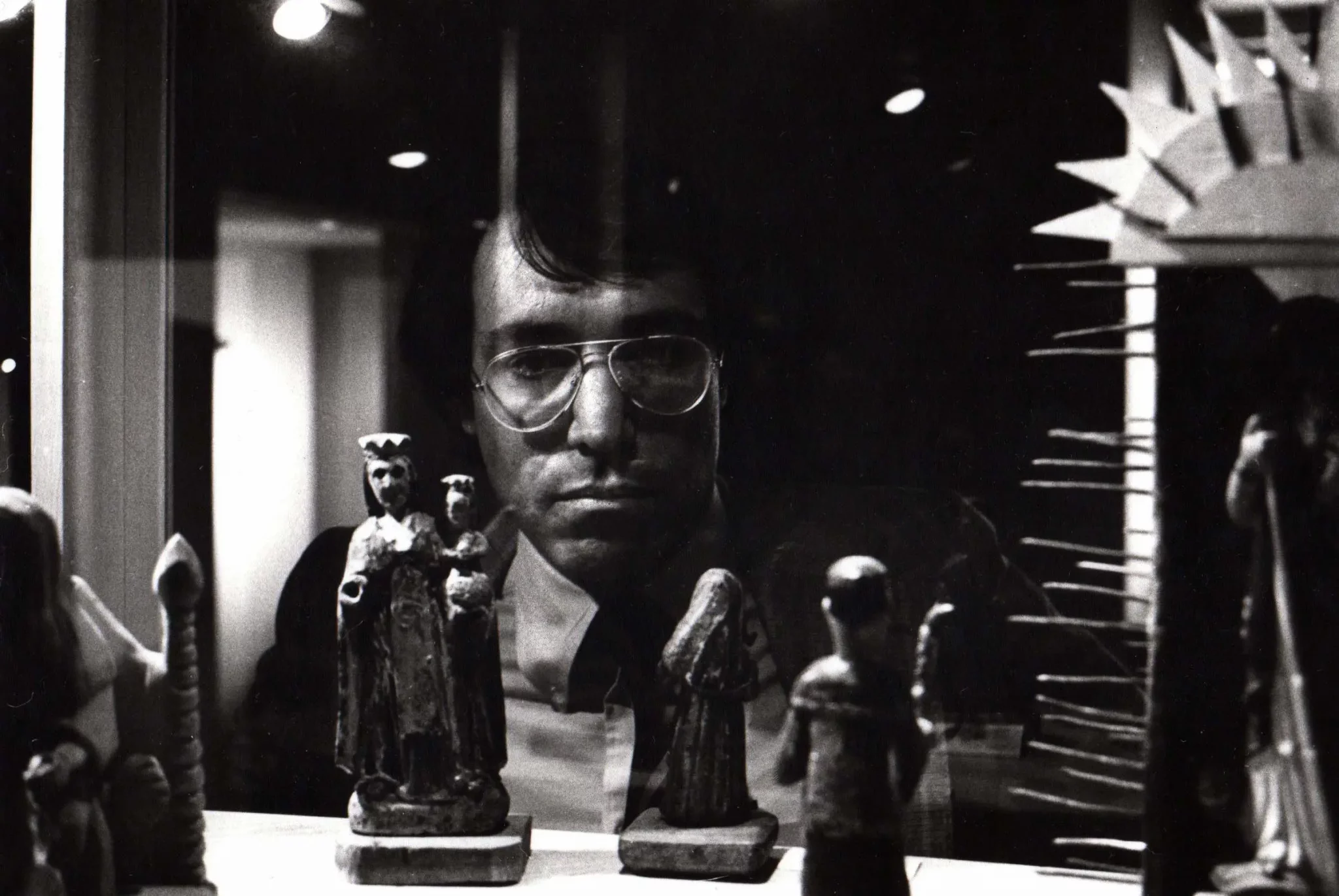

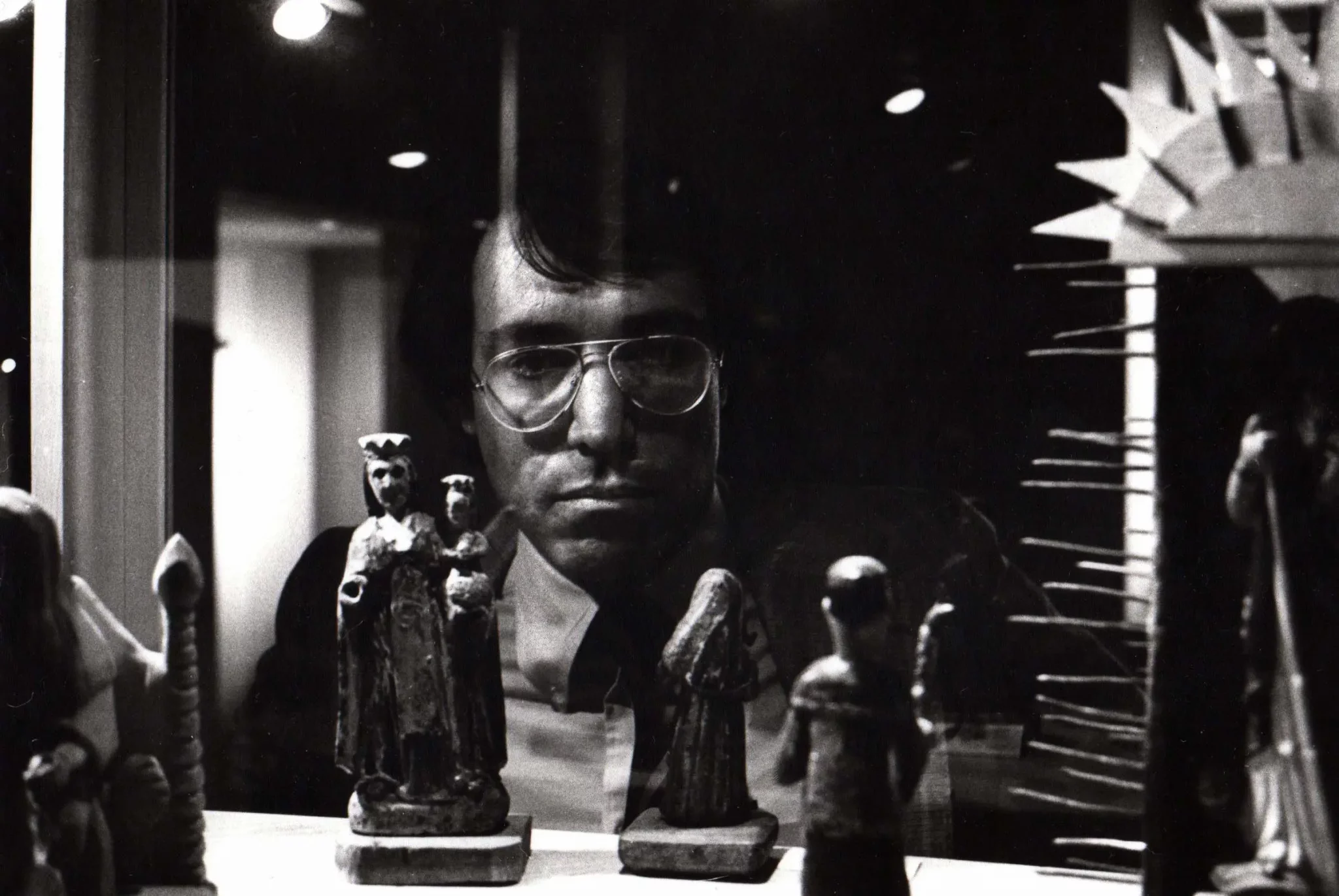

Jack Agueros with the Santos de Palo exhibit at El Museo del Barrio, New York City, 1979 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

When Edwin Rodríguez was working on my father’s archive at the Smithsonian American History Museum, he asked a question I’m sure many of us who knew him are asking these days: What Would Frank Espada Do?

With a racist president, a distracted or apathetic population, and so many causes competing for our attention, it’s easy to feel overwhelmed at times. But this is just where we need our ancestors and our great artists to remind us of all we are naturally heirs to; to remind us of our history and strengths, of our beauty, and courage and creativity. We can then get back to work as far as we are able, advocating, and caring for the needs of the neglected peoples of our time.

As Edwin says in his essay:

I think of Frank Espada and his work, both as a photographer and as a community leader, and comprehend his vision of the world. He saw beauty in every photograph, but understood that the most important thing he could do was help others through their struggles and listen to their stories when the world surrounding them chose to turn a blind eye.

Five kids on a country road in Puerto Rico, 1967 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

For further reading:

A Sketch of Frank Espada’s Life, accompanied by his photographs, by Jason Espada

My father’s photographs:

thefrankespadagalleries.com

Let America Be America Again by Langston Hughes

The New York Times: The Puerto Rican Diaspora by David Gonzalez

Reframing America’s Modern-Day Colonialism: Puerto Rico in Context in 2017 by Jason Espada

Doña Pura, Manhattan Valley, NY, 1981 (Photo by Frank Espada/Courtesy of Jason Espada)

What Would Frank Espada Do? by Edwin Rodríguez

The Puerto Rico tourists rarely see, and the U.S. role in Puerto Rican poverty by Denise Oliver-Velez

Our Fellow Americans by Frances Negrón-Muntaner

The Emptying Island: Puerto Rican Expulsion in Post-Maria Time by Frances Negrón-Muntaner

***

Jason Espada is a writer and classical musician living in San Francisco. He is a steward of his father’s photography and the founder of abuddhistlibrary.com. These days, Jason’s focus is on the natural connection between spirituality and social action. His new website is jasonespada.com.

Jason, We are also proud to have a collection of your father’s photographs and papers at Duke University

https://library.duke.edu/rubenstein/findingaids/

We celebrated his work with an exhibit I co-curated in 2012

http://exhibits.library.duke.edu/exhibits/show/espada

[…] Latino Rebels article about recent history of Puerto Rico, worth a look, highlights a new to me book of photography: The Puerto Rican Diaspora (also […]

[…] work now. Now more than ever when it comes to Puerto Rico, we need this kind of knowledge… Puerto Rico Update – A Personal Reflection * * […]