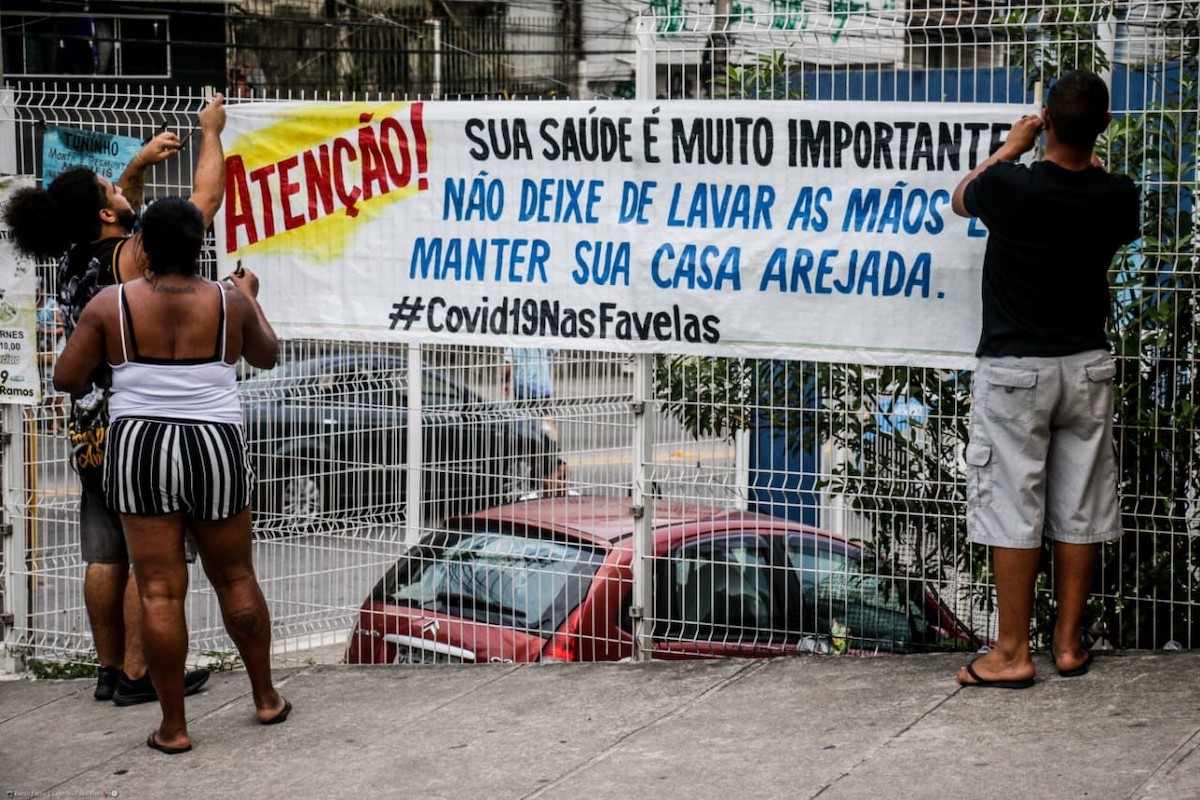

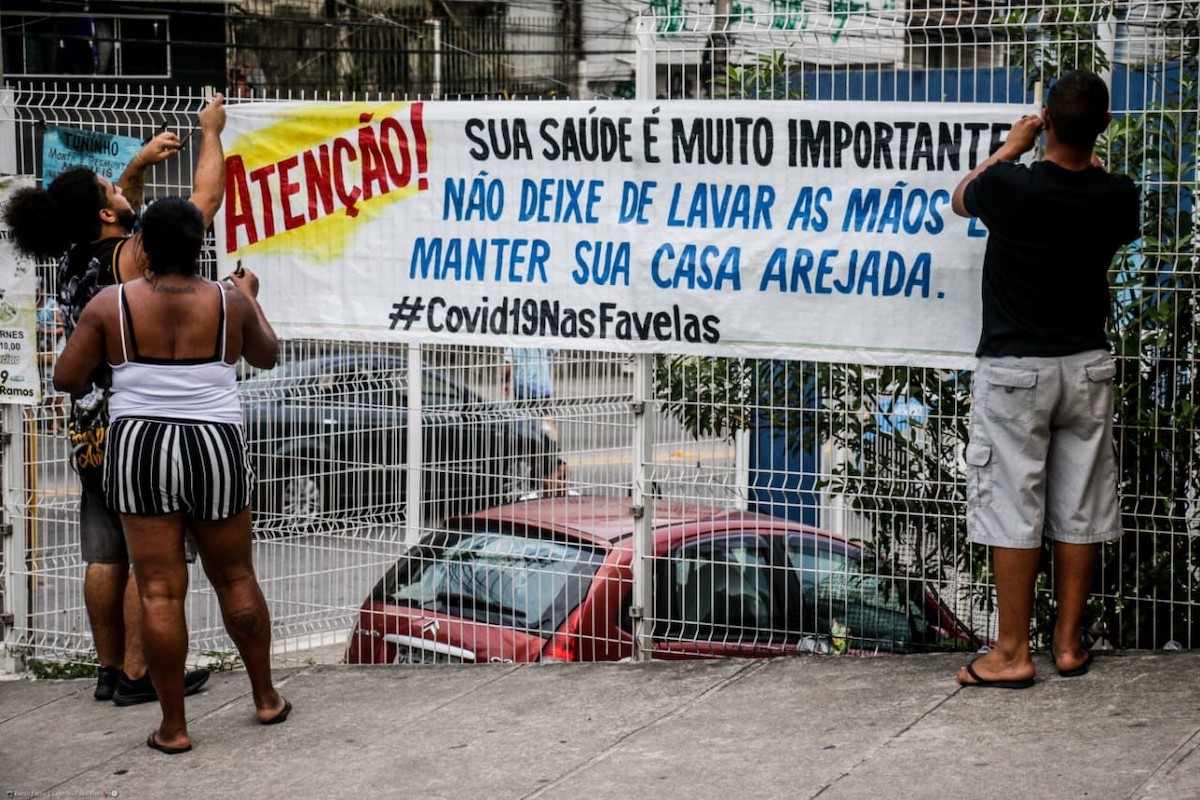

Residents of Complexo do Alemão hang warning signs with information about COVID-19. (Photo courtesy of Bento/Coletivo Papo Reto)

By Marina Guimarães

RIO DE JANEIRO — Two of the most important steps to prevent the spread of the novel coronavirus are washing your hands and practicing social distancing. But for Brazil’s poorest, following those guidelines is nearly impossible

“The mayor sent cars notifying us that we should wash our hands with soap, and stay at home for the next few days,” said Tamires Paulino, a resident of Morro dos Macacos. Paulino lives with her five children in Rio’s second biggest favela.

“But how does he expect us to wash our hands if we don’t even have water? Some of us receive soap donations, but you can’t really wash your hands only with soap,” she said.

The threat of the coronavirus to Brazil’s low-income communities has hit home in recent days. Rio de Janeiro’s first victim of the coronavirus was a 63-year-old housekeeper who worked in Leblon, one of the most exclusive neighborhoods in the country. The woman contracted the virus after her boss arrived from Italy and was waiting for her test results.

President Jair Bolsonaro compared the virus to a “small flu” on live television on March 24. In the same speech, he urged people to go back to work and said the mainstream media in Brazil was promoting hysteria. During the address, Brazilians banged pots and pans from their windows as a form of protest. In Brazil, the pandemic has already led to 77 deaths and 2,985 confirmed cases.

On March 22, the virus had reached at least four favelas in Rio de Janeiro. By March 26, Rio de Janeiro reported 421 cases and six deaths. The struggle to prevent the spread of the coronavirus has directed attention to places where the state is often absent. Residents of favelas are stepping in, educating their neighbors and addressing chronic problems, like water shortages, that will exacerbate the virus.

Rio’s Complexo do Alemão. (Photo by Neila Marinho)

Werneck adds that the precarious conditions in the city’s favelas go strictly against the recommendations of the World Health Organization.

“What we see, on the other hand, is the mobilization of civil society in order to contain advances of the COVID-19 in more vulnerable areas throughout the country,” said Dr. Werneck.

Organized criminal groups and militias are trying to control the situation by imposing curfew in several favelas in Rio de Janeiro. According to messages delivered through social media and cars with loudspeakers, favela residents received death threats if seen on the streets after 8pm.The groups also oriented people to stay inside and only leave their houses in case of extreme emergency.

Other favelas residents are working to spread reliable information about the virus. Near Morro dos Macacos, communicators have been working hard to raise awareness. “Voz das Comunidades” started out in 2005, when 11-year-old Rene Silva decided to create a newspaper for the residents of “Morro do Adeus,” one of the favelas that form the “Complexo do Alemão” in Bonsucesso, in northern Rio. The publication became famous after Rene transmitted events of the military occupation in the Adeus slum in Rio live on Twitter in 2010.

Hoje, 28 de novembro, faz 8 anos daquele momento da ocupação do Complexo do Alemão. Vamos recordar? pic.twitter.com/JuVGGENCal

— Rene Silva (@eurenesilva) November 28, 2018

Today, the communication platform works in nine different favelas in Rio de Janeiro to highlight social issues that residents face and to bring attention to people whose voices are not necessarily heard by mainstream media.

“Our main concern now is to do the best job we can, to alert and to give support to the ones who need it inside our communities,” Neila Marinho, a journalist and the organization’s press coordinator, told LAND.

“Voz das Comunidades” broadcasts live video streams on Instagram informing the population about daily news. As the pandemic spread, the organization started to dedicate time and space to educate people about its consequences. Their broadcasts became famous in the communities and reach thousands of viewers.

The next weeks will determine how the coronavirus impacts the favelas of Rio de Janeiro. The tightly packed neighborhoods lack the infrastructure necessary to prevent the spread of the virus. Public hospitals are likely to be overwhelmed. But civil society organizations and groups of neighbors are busy working to close the gap.

“We just hope that people follow our instructions,” said Marinho. “And that we make it out of this crisis quickly.”

***

Marina Guimarães is pursuing a joint master’s degree at NYU in journalism and international relations after concluding her BA in political science, with focus on international relations and the Middle East, in Nuremberg, Germany. She is also the author of her own blog, Between Borders, where she writes about refugees, the Middle East and Brazil, where she was born and raised.