Álvaro Huerta in front of mural in the Ramona Gardens public housing project (20005 photo by Pablo Aguilar)

Growing up on the mean streets of East Los Angeles —the Ramona Gardens public housing project or Big Hazard projects— I witnessed/experienced police abuse.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J2hg_d-spwo

For myself, along with childhood homeboys and siblings, it occurred so frequently, where I naively thought that all Americans feared the cops. It first starts as fear; it then morphs into hate.

“Hands up.”

“Hands behind your back.”

“Get against the wall.”

“Get on your knees.”

In the projects and other racialized communities, in contrast to lily white suburbs, the cops represented (to the present) military occupation forces. Hence, why should we cooperate with them? Why should we inform or snitch on our Brown neighbors? This is why we create our own street code—our own mores or morality to survive. Trust and respect must be earned!

It’s all about context. In the lily white suburbs, when something bad happens, the privileged white residents don’t hesitate to call the cops for prompt responses. In the projects or America’s barrios, that’s a recipe for disaster. You call the cops and then you often become the suspect. How is it that for those of us who grew up in the barrio, when pulled over by the cops, we frequently “fit the description?”

I guess “all Mexicans” look alike.

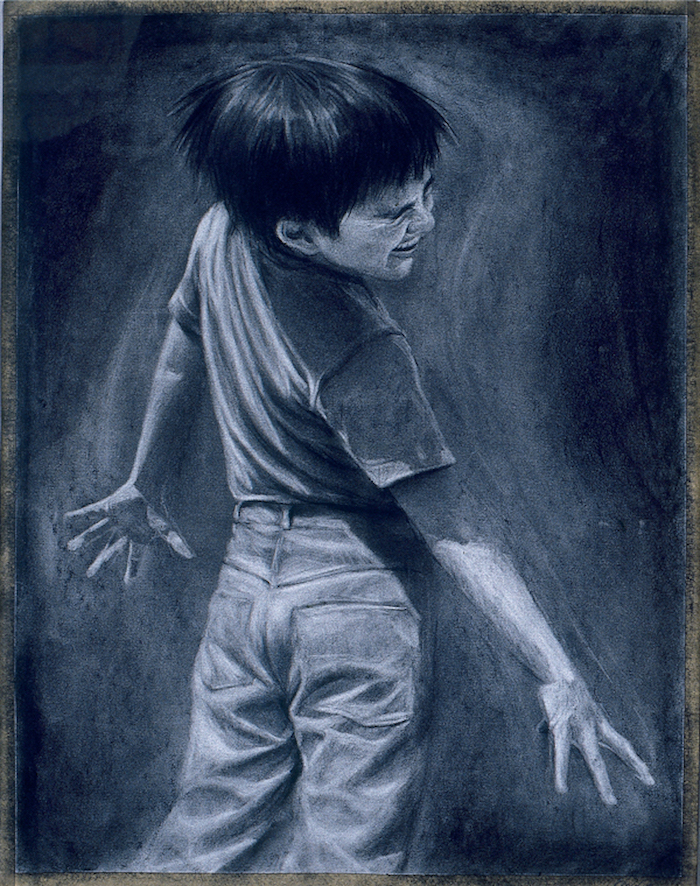

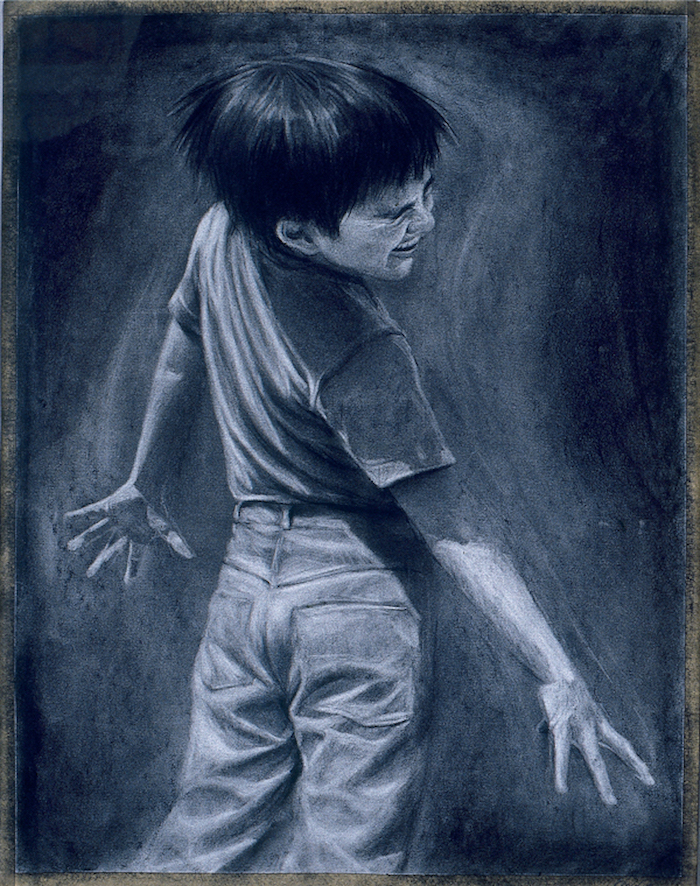

“Untitled” kid being shot by Salomón Huerta, 1991

As a Chicano kid who loved to play sports, where my “gang application” was rejected for being too thin, I remember the first time the cops harassed my friends and I. When bored, we would jump the fence at Murchison Street Elementary to play on the schoolyard. One day, the cops arrived in several patrol cars, where they forced us on our knees with our hands up for what seemed an eternity. (Did I mention that the asphalt was hot?) We were just poor, Brown kids playing baseball with used gloves and torn baseballs. We weren’t white nationalists “protesting” with tiki torches in Charlottesville, Virginia. We weren’t white militia (heavily armed) taking over the Michigan Capitol in Lansing. As Brown kids, we received a clear message from the state that took me years to figure out, as I gained political consciousness: “We’re treated like foreigners in our own land.”

On a regular basis, the cops patrolled the projects and hunted Brown “suspects.” Just like the abject poverty we experienced, patrol cars and helicopters were omnipresent. Before taking the “Brown suspects” to be booked at the Hollenbeck Police Station, the cops would often rough up the homeboys. I guess they couldn’t wait for the courts to inflict bodily and mental pain on the alleged suspects? I guess the legal concept of “innocent until proven guilty” doesn’t apply to Brown bodies?

On too many occasions, their cruelty resulted in murder of Brown people. If that’s not criminality, like in the case of Eric Garner in New York or, more recently, George Floyd in Minneapolis (among countless others), I don’t know what is? Speaking of particular cases, let’s not forget about the countless Chicanos killed by the cops, like in the case of José Méndez, a 16-year-old killed on February 6, 2016, in East Los Angeles. While cop killings of Chicano youth and men don’t get reported and protested at a national level similarly to African Americans —where I’m in solidarity with my Black brothers and sisters— the most famous case of a Chicano killed by the cops goes back to August 29, 1970, with murder of the journalist Ruben Salazar during the massive Chicano Moratorium protest.

Of the many times the cops pulled me over and harassed me, the closest I got to death was when a cop (LAPD) pulled a gun on me. What “crime” did I commit? I made a rolling stop while teaching myself how to drive the 1967 Ford Mustang my sister Catalina gifted me. While I was nervous looking at the barrel of his black, shiny gun, truth be told, I wasn’t traumatized. Yet, I could’ve easily been killed. What if I made a wrong move? What if I said the wrong thing? What if I started to run out of panic or fear? At the end of the day, I was already desensitized to the state violence or the threat of it in the projects! Even when my Mexican mother Carmen heard the news via the “comadre network” (more powerful than DSL, especially since didn’t have internet back in the day), she didn’t panic or flinch. As I rushed to watch my favorite television program, Good Times, she calmly asked me: “¿Tienes hambre?”

Once I left the projects as a 17-year-old math major at UCLA, it seemed like the cops followed me from the Eastside to the Westside. One day, while driving my 1970 VW Beetle with my Chicano and Chicana classmates in West Los Angeles, two cops pulled us over for no reason.

“What are you all doing in this neighborhood?,” one cop demanded to know.

Hazard graffiti in the Ramona Gardens public housing project (2005 photo by Pablo Aguilar)

While we didn’t get “the talk” that Black parents have with their kids, we knew the dire consequences of demanding our civil rights, where we peppered our responses with: “Yes, sir; no sir.” After being harassed, we were quickly reminded that we don’t belong.

Years later, once I became a community activist, my younger brother Noel informed me of the terrible news that the cops (Los Angeles County Sheriffs) killed a resident from the projects, Arturo “Smokey” Jiménez. Smokey, a friend of my younger brother’s, was 19 years old and unarmed with the cops killed him on August 3, 1991. The killing of Smokey by Deputy Jason Mann resulted in a riot.

“Smokey Mural” by Salomón Huerta with help by residents of Ramona Gardens, 1992

Eventually, apart from a state investigation, the civil rights attorney R. Samuel Paz successful sued and settled on behalf of Smokey’s family for wrongful death against Deputy Mann/Sheriff’s department for $450,000. Unfortunately, in terms of abuse case (more like cases of brutality!), this legal victory is the exception—not the rule.

¡Ya Basta!

We must stop systemic police brutality against Brown and Black bodies for the sake of America’s humanity.

***

Álvaro Huerta, Ph.D., is an Associate Professor in Urban & Regional Planning and Ethnic & Women’s Studies at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona. Among other publications, he’s the author of the books: Reframing the Latino Immigration Debate: Towards a Humanistic Paradigm (2013) and Defending Latina/o Immigrant Communities: The Xenophobic Era of Trump and Beyond(2019). He holds a Ph.D. in City and Regional Planning from UC Berkeley. He also holds an M.A. in Urban Planning and a B.A. in History from UCLA.

Alvaro, your essays are, as always, timely, poignant, and honest. I had forgotten about the Smokey Jimenez killing and resulting riot at Ramona Gardens in the summer of 1991. Honestly, I was very drunk for much of 1990-91, but I learned about the event later, when I sobered up in 1992. Like you, I was stopped at gunpoint: luckily mine happened in 1987 at a local park at night and the grass was wet and cool as I spread eagle on it, my fingertips barely touching those of my two Mexican-American friends. Even in the night gloom, the barrel of that service revolver was gaping in its eagerness to obliterate us. The only thing between me and death was the shaky finger of the rookie cop who was quick on the draw. I remember biting the damp grass, tasting its tartness in the cool summer night and thinking, “Guess I was right about never making it to 30.” After the older, seasoned cop got his partner to holster his weapon and had us stand up and hand over our IDs, I, like you, was not resentful or even able to connect the dots. I assumed it was because of our age (and yes we were drinking underage); it was only years later, after I witnessed more of life, after I befriended police officers who would talk frankly with me, that I realized mis mejor amigos might have been the reason for the felony approach on three poor but sun-tanned Southern California teens, two of Mexican descent and one who could trace his white ass back through five generations of native California fruit-pickers, wasting away a Friday night with a 12-pack of MGD and nowhere else to go.

Good work Alvaro. A very timely piece indeed.

What’s with this new race called brown when referring to Latinos??? I thought it would refer to mix black with white race… I am of hispanic and I am not brow but light tan skin color who lived in Ramona Garden across from the Nico’s store. I went to Hollenbeck Jr. High and from my understanding the cops you are talking about were of Latino and NOT white officers. And yes most kids are neglected growing up there because I clearly remember my young cousins who used to play in the train tracks and jumping on those passing trains until one of the boys lost a foot when he jumped off the train… It’s not the cops who are the problem in East Los Angeles. Where are the parents those young kids are climbing school fences and jumping up and then down the trains??? trains.