Nidia Bello stands in her bodega, Sto Domingo Grocery, in New York City’s Washington Heights neighborhood. (Muriel Alarcon Luco/Latino Rebels)

WASHINGTON HEIGHTS, New York — Since Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit movie In the Heights was released in June, Nidia Bello’s customers have multiplied.

Every week, visitors from the five boroughs as well as Florida and Pennsylvania, and even other countries like Mexico, drop in to have a look around. They want to confirm that her bodega on 196 Audubon Avenue in Washington Heights is the same one run by the fictional Usnavi de la Vega in Miranda’s film.

To all who ask, Bello, 65, wearing her crisp, button-down shirt, nods and smiles behind her mask.

She has not seen the movie, but Juan Esteban De Jesús, her youngest son, did back when the movie first hit the theaters. “Changing a little thing here and another there, I felt that the movie was basically the story of us,” he said recently.

Based on the Tony Award-winning play, In the Heights romanticizes a Latinx neighborhood with joyous songs and elaborate dances. Behind the set is a much more complicated story.

Like in the movie, there was a death in the bodega family. Bello’s husband and business partner died several months before In the Heights was released, and Bello is still grappling with the loss.

For three decades, Sto Domingo Grocery —named after the abbreviation for Santo Domingo, her birthplace in the Dominican Republic— has been Bello’s second home. She and her husband Esteban De Jesús opened the store in 1993 and raised their two children within its walls. Bello knows the price of every product on the shelves.

The cramped space, decorated with Christmas lights and Dominican flags, is the meeting point for many immigrants searching for products from their home island. There’s El Far coconut cookies and yun yun, the D.R.’s version of a snow cone.

Until 2021, anyone who came to the bodega to buy Guarina saladitas or Ranchero liquid seasoning heard the sound system blasting melodies of Cuban guitarist Eliades Ochoa and salsas by the Venezuelan Óscar D’León.

But on February 19, the music stopped. That’s when Esteban died of a heart attack caused by complications from multiple sclerosis. He and Bello had contracted COVID-19 in March of 2020, and doctors believe the illness accelerated his condition.

Sto Domingo Grocery in New York City’s Washington Heights neighborhood, the main setting of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit 2021 movie, ‘In the Heights.’ (Muriel Alarcon Luco/Latino Rebels)

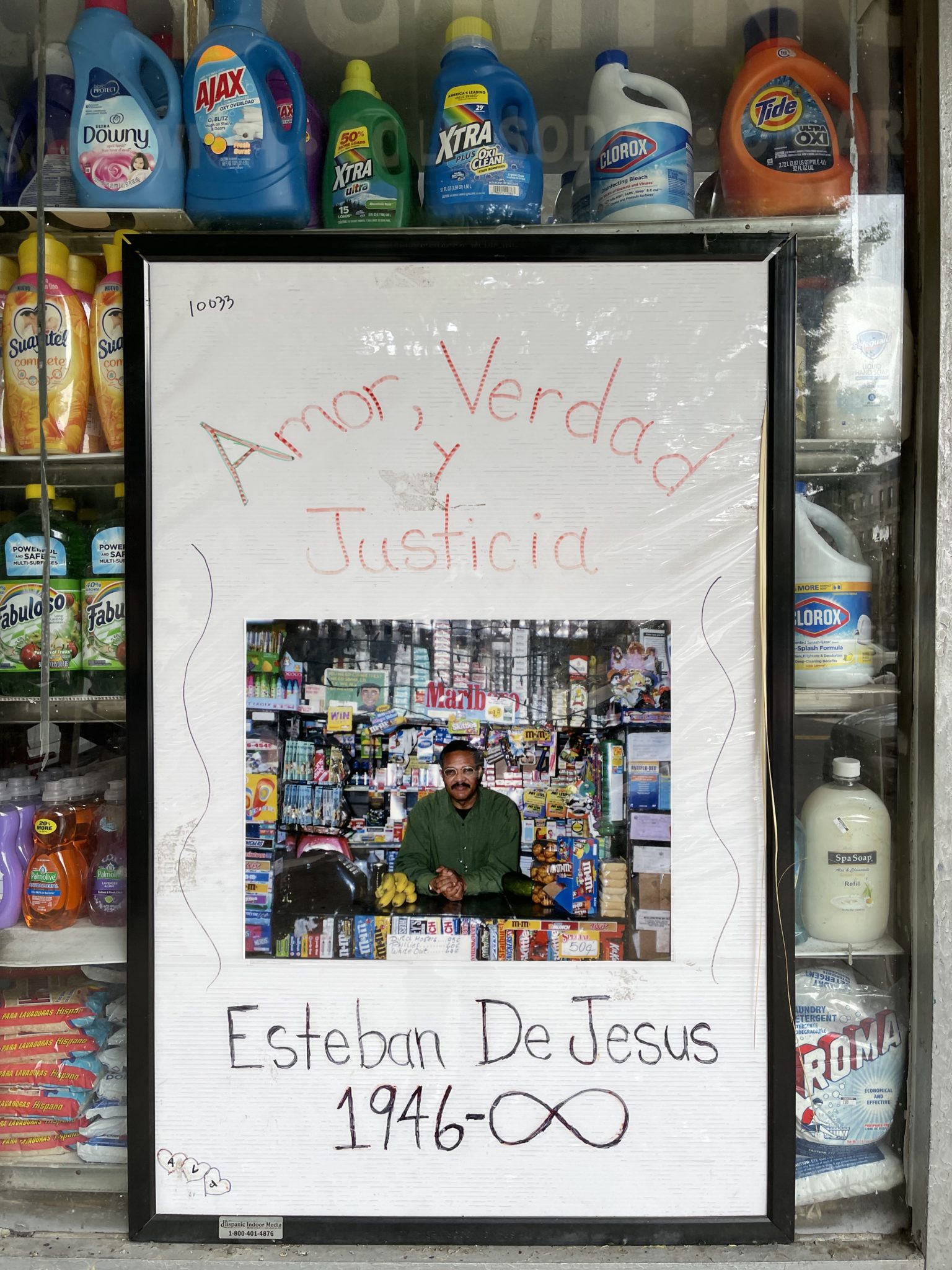

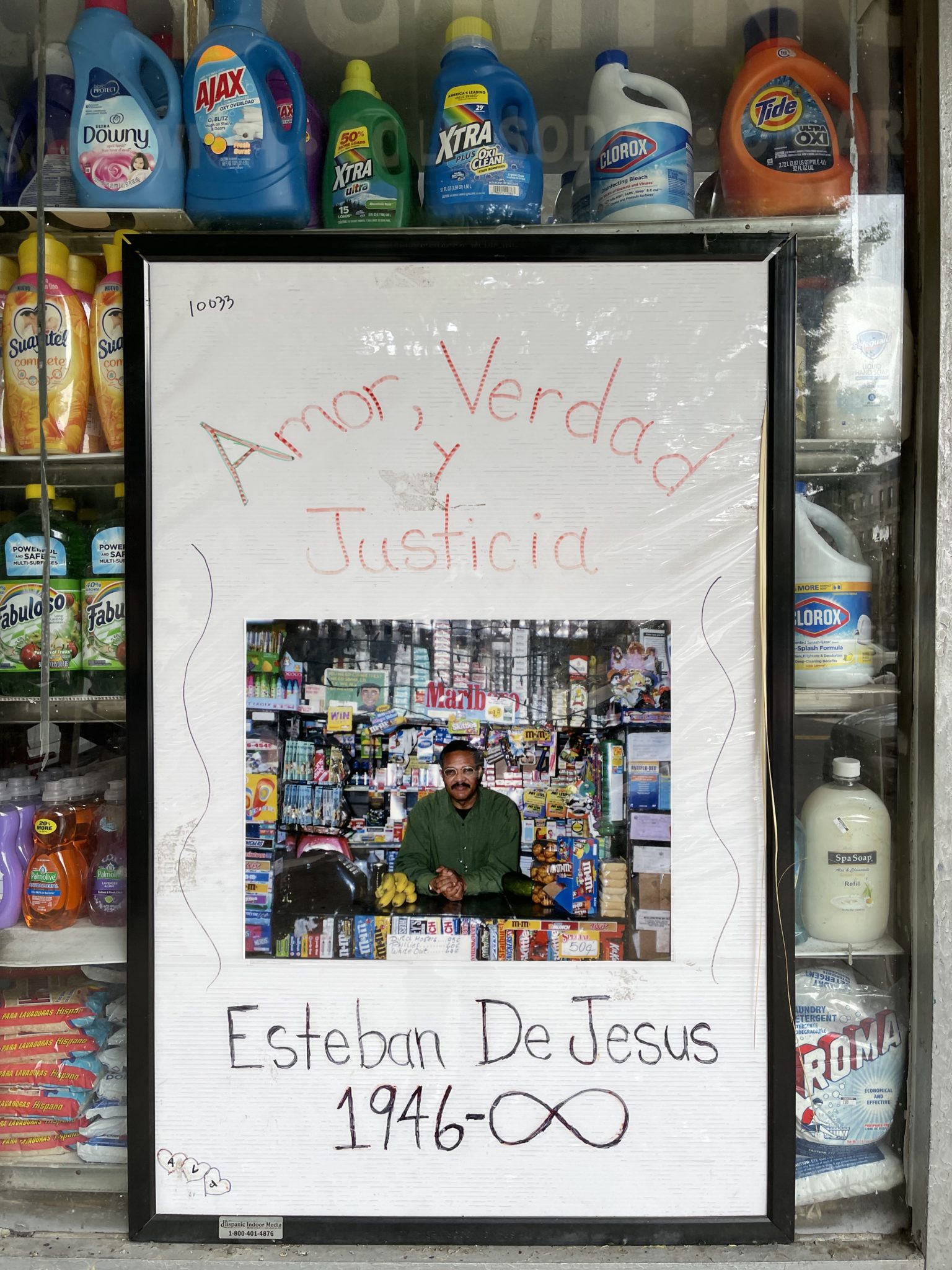

While movie fans snap photos of the iconic storefront, its windows crowded with bottles of laundry detergent, Ajax, Clorox, and Windex, there’s a new addition to the facade, one that wasn’t included in the movie.

In the shade of the bodega’s green awning stands a poster with Esteban’s photo. His hands are clasped on the counter and he’s surrounded by cigarettes, candy, and bananas. Above his picture, in his son’s careful handwriting, reads: “Love, truth and justice. 1946 – ∞.”

Esteban and Nidia were both employed as teachers in Santo Domingo when they quit their jobs and left the Dominican Republic in 1983, dreaming that New York would place them in a better financial position.

“The money you made wasn’t enough to live a little better,” Bello says. “We had faith that things here were going to improve us.”

They left their children, who were then five and three, and settled in Washington Heights, encouraged by Bello’s sister who had already made the journey.

At first, the couple worked for a travel agency. They sold airline tickets and provided a remittance service that enabled people to send funds to relatives in other countries. But then Esteban and a friend took jobs as salesclerks in a bodega at the intersection of 187 Street and Saint Nicholas.

De Jesús liked his role at the bodega. So, several years later, he acquired his own store, Sto Domingo Grocery. Soon thereafter they brought their children from the Dominican Republic to live with them in the neighborhood.

Three decades later, the bodega has maintained its same dimensions: three aisles packed nearly to the ceiling with groceries and a tiny, hidden kitchen near the counter. Outside, the scene has not changed either; a group of older Dominicans meets frequently to play dominoes at a table on the sidewalk.

More Dominicans live in New York than any other city in the world, except for the Dominican capital itself, according to the Department of City Planning. The Census 2019 estimates that 97,488 Dominicans live in Washington Heights, nearly half of the neighborhood’s entire population, followed by Mexicans (13,276) and Puerto Ricans (11,745.)

Although the film drew some criticism for not casting enough Black Latinos for its characters, Ramona Hernández, the director of the Dominican Studies Institute of the City University of New York, has a different complaint: she feels the movie was almost too inclusive. It did not focus enough, she says, on Dominican culture in Washington Heights, which is far more representative of the neighborhood than the other Latinx groups living there.

She notes that Dominican bodegas are family businesses in Washington Heights, saving on resources by employing relatives. Bodegas are “bastions” of culture, she adds.

“To the extent that Nidia maintains her showcases, she is also maintaining the Dominican culture and identity,” says Hernández. “She is a very important part of its space.”

Despite the fact that lottery tickets are omnipresent in New York bodegas, Bello and her husband did not play in their nearly 45 years of marriage. For Esteban, earning money through lottery tickets “was like taking money from one person to give it to another,” Bello says, recalling his policy: “If someone wants a peso, I will give it to them. But play? Let no one speak to me about it.”

Juan Esteban says that instead of counting on luck, his father used the profits of the bodega to buy a house in the Dominican Republic, along with land and a small three-story building to rent. The building, he says, has just been completed.

“He was preparing all of this so that we would not have to continue in the day-to-day hustle,” Juan Esteban said.

A memorial for Esteban De Jesús is displayed outside Sto Domingo Grocery, the bodega he and his wife Nidia owned and operated in Washington Heights. (Muriel Alarcon Luco/Latino Rebels)

His father preferred to keep a low profile. When the In the Heights crew came to test the location, he left it to Bello and their son to decide whether to welcome them or not.

Between June and July of 2019, the production crew was stationed outside their store. Juan Esteban was the family’s main liason with the filmmakers because he speaks English.

But his father understood the importance. “You could see his emotion,” Esteban said.

The In the Heights team sent Bello tickets to watch the premiere at the historic United Palace movie theater three blocks from her bodega, but she declined. “I don’t feel up to it,” she says. “Not yet.”

Esteban had his first heart attack 10 years ago. But by 2020, at 74, he was healthy, his wife recalls. During the first frantic months of the pandemic, their store was deemed an essential business to the neighborhood.

“We were always open,” Bello says.

They both caught COVID but had mild cases.

Just like the oft-repeated phrases of the movie’s Grandmother Claudia, Bello says her husband lived his own version of “paciencia y fe,” patience and faith. At no point did he complain, she says. “He was a very peaceful man. He was always with God in his mouth.”

In February 2021, though, his condition worsened. Juan Esteban remembers his father asking the nurse to listen to Ochoa’s guitars and D’Leon salsas in the hospital room, to which he added bachatas from the Dominican Eladio Romero Santos.

He died in his wife’s arms.

Juan Esteban says that while his parents had become United States citizens, his father had promised Bello they would sell the business and return to the Dominican Republic to retire.

Bello adds that this year they were supposed to make their “sueñito,” their little dream, come true. “But God’s plan was different,” she says from behind the counter.

Her regular customers and the routine of work keep Bello going. “This community regards you as your family,” she says, adding that she is staying put.

“God has me on my feet.”

***

Muriel Alarcón is a Chilean journalist reporting on Latino communities in New York. Twitter: @murialalu

This article lends relevance and connectedness to the Dominican culture, but also to the culture of English speaking

Caribbean immigrants, as honest work is a hallmark of both.