Latino leaders must begin leveraging their power to speak out against widespread imprisonment

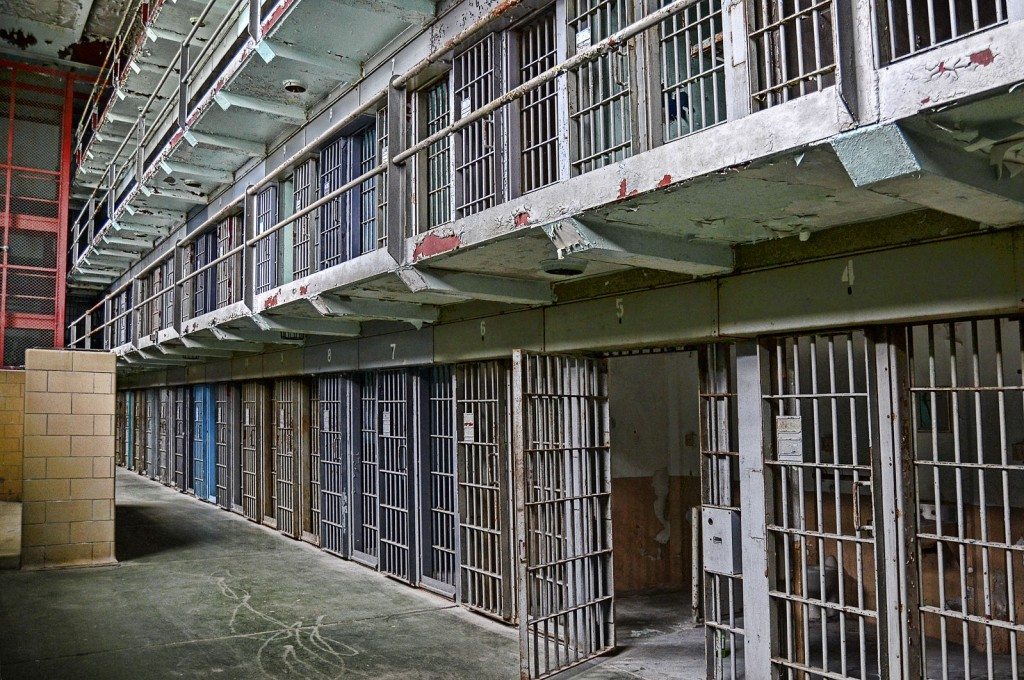

It is 2013, over 40 years after President Nixon launched the War on Drugs in response to conservative demands for “law and order” in the post-Civil Rights era. Every president since has intensified the government’s war efforts, enlisting Congress, the judiciary, and local law enforcement as loyal foot soldiers in ostensibly ridding America’s streets of the drug problem. The result has been a consortium of laws to grease the wheels of a giant, militarized police apparatus that has swelled the prison population from 300,000 in the early 1980’s to nearly two and a half million now—a phenomena that can be explained almost entirely by decades of escalated policing, rather than an actual increase in crime (it actually decreased).

The most disturbing feature of this trend, activists have long said, is that those most targeted for arrest and harsh sentencing are African-Americans and Latinos. Law professor and civil rights activist Michelle Alexander has gone as far alleging that the mass incarceration of black Americans is tantamount to a contemporary manifestation of Jim Crow—a method of racial control far more subtle than its predecessor. She isn’t the only black leader to condemn pervasive imprisonment resulting from draconian drug laws—voices as mainstream as Oprah and Will.I.Am have also taken to public channels to protest the merciless aggression with which the criminal justice system has decimated families and communities.

Yet while a number of influential African-Americans have spoken out vehemently against mass incarceration, Latino leaders have proven inept at mirroring this outrage. Overall, our leaders have failed to take a bold stance on policies that have wrought unspeakable damage upon our people, and this failure may be indicative of a deep crisis of identity within our community.

It is not as if we lack adequate information. Although the terrain of data on imprisoned Latinos is harder to traverse than other groups because of its often incomplete, ambiguous nature (owing the confused designation of “Hispanic” as an ethnicity rather than a race), the numbers that we do have are revealing in their own right: as of 2012, Latino men were incarcerated at a rate nearly 40% higher than whites (1,822 per 100,000 compared to 708 per 100,000). In all, one in three persons held in federal prisons is Latino, and Latinos are four times as likely as whites to end up in prison.

To truly observe the racially biased nature of unequal incarceration, however, one must examine drug-specific arrests. Owing to the incomplete nature of such statistics at a national level, we can use select metropolitan data as proxies for understanding broader phenomena.

In New York City, Latinos are arrested nearly four times as often as whites for drug possession, even though government records consistently indicate that whites are more likely than any other racial or ethnic group to use and sell drugs. In California, Latinos were disproportionately represented in drug arrests in all cities within Los Angeles and Orange County, along with fifteen other major cities. In Alhambra, a city with a population of 85,949, Latinos made up only 35.5% of the population but 74.6% of marijuana arrests. Given the macro forces that undergird these figures, one can intuit that these arrests are happening by extension on a national scale.

For a person with a felony conviction, the consequences of incarceration extend far beyond time spent in prison. Reduced to second class citizenship because of the black mark on their record, a former prisoner is left alone to navigate a world in which gaining employment, housing, financial aid for higher education, and other benefits is significantly more difficult if not impossible. These effects ripple out to soil the person’s family’s lives as well, and, if he or she has children, potentially enforcing the cycle of imprisonment and disenfranchisement for a new generation.

Despite all the suffering wrought by the War on Drugs on Latino communities, Latino leaders seem as if they’d rather sweep the issue—and those most affected by it—under the rug, out of sight and the way of their efforts to acclimate into elite American society.

A review of Latino Leader Magazine’s 101 most influential Latinos of 2013 features mostly pale visages posing in front of American flags or underneath the flattering glow of studio lighting.

One would imagine that these leaders, most with palpable European heritage, likely look much different from the average Latino inmate, who we know anecdotally tend to possess more indigenous features. Perhaps this ethnic variation, and the historically rooted idea of superiority that accompanies it, partially explains the disconnect between the Latino elite and the imprisonment issue within our community. This may also account for why contemporary Latinos in positions of power are notoriously more conservative on social and economic issues than African-American leaders. An uncertain sense of identity may be advantageous for someone hoping to chameleon his or her way up the social hierarchy, but it is supremely detrimental for shoring up a sense solidarity with our most vulnerable brethren.

The old adage of a chain only being as strong as its weakest link should resonate loudly with Latino leaders. Mass incarceration hinders the potential of millions and destroys the precious familial bonds on which we have traditionally prided ourselves. If our community’s leaders are going to shirk their responsibilities in advocating for the most aggrieved among us, then perhaps our communal ties are more precarious than we would like to admit.

***

Aaron Cantú is a Brooklyn-based journalist @alternet @truthout @thenation. A “revolutionary generalist” who focuses mostly on drug law, criminal justice, and [misc], you can follow Aaron on Twitter @aaronmiguel_ or visit his site: aaronmiguel.com.

The writer should consider the population of Alhambra on a whole before implying that the arrests records are skewed for reasons other than perhaps the Latino population just engages in the use of and distribution of marijuana more than the other races in that city. In Alhambra for example, the city has a 53% Asian population. I’m pretty sure culturally speaking, Asians smoke far less weed than do Latinos. The black population in Alhambra is less than 2%. Gee, I wonder why the author did not cite the arrest records of blacks in Alhambra? Im all for ending the war on drugs, but not by using questionable information that does not necessarily paint a fair picture.

PatrickBonilla Don’t understand how you can allege someone is making a conjecture and then make a bald conjecture yourself (“Latino population just engages in the use of…marijuana more than other races.”).

Before Alhambra was mentioned, it was stated that on average at a national scale, whites use marijuana more than blacks or Latinos (based on government data). True that doesn’t definitively establish rates of use in Alhambra, but extrapolation can be made from national dataset. http://marijuana-arrests.com/graph5.html

aaronmiguel_ PatrickBonilla I grew up in a city that neighbors Alhambra, so i speak from experience. It was my experience that Asians by and large did not engage in marijuana use in the way Latinos did. I had my first hit of a joint at about 11 or 12 years old. While it was not even close to a daily thing for me, it was something me and my young friends started at a relatively young age. This was in the mid 70’s. My recollection was that during this time, the Asians in the community were considered , “squares”. Does that mean the 53% of Asians in Alhambra do not use marijuana? No, of course not, but I would bet good money the percentages are far less than the Latino population. When i was a kid, there was a lot of peer pressure to smoke and drink at a young age. I don’t think that exists to the same extent in Asian cultures. This is a quote from a book by Andrew Golub called “The Cultural/Sub-cultural Contexts of Marijuana Use at the turn of the 21st Century”, where he states the following:

“Drug use in the family households of Latino and Asian Americans was less common than in African American homes. Slightly less than 30% of Latinos cites family members drug use, and those were primarily among their siblings. Ten percent of Latinos had fathers who used and their drug of choice was predominantly marijuana. Of the Asian respondents, 11 percent had family members who were users”

PatrickBonilla anecdotal knowledge is can give good insight, but taking too much stock in it can obscure broader truths. I’m not disputing your claim about Asians smoking less than Latinos because I have nothing with which to refute it. But I am refuting your assertion that the extreme discrepancy in arrests within the three acknowledged racial/cultural groups (white, black, Latino) reflects an extreme discrepancy in usage. It doesn’t.

Culturally, I too saw my fair share of marijuana usage while growing up in a predominantely Latino community. But it would be disingenuous of me to presume my experience represents the experience of millions in this country, and it would be even more erroneous to think that my experience verifies an assumption that any group uses more than another. Once again, official data says otherwise.

While professing to be ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html profoundly disturbed’ by the aggression of anti-Semitic Germany, Roosevelt continued his special http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html friendship for Soviet Russia http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html after its attacks upon Outer Mongolia, Poland, Latvia, Esthonia, Lithuania and Finland. Professing an adoration for ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html democracy’ he refused, as the Jews control 90 percent of the scrap iron business, to invoke the Neutrality Act against http://cintaberita.com Japan in its http://raksasapoker.com/war on China, or against Russia when, with Germany, she invaded Poland and attacked Finland. He extended a warm welcome to the Communist Ambassador Oumansky when he presented his credentials and, on the same day, displayed marked coldness toward the newly appointed Ambassador from Christian Spain