Editor’s Note: This story was developed as a collaboration between Carolina Drake (@CarolinaADrake on Twitter) and Luis Marentes (@marentesluis on Twitter). Since our site does not allow for double bylines, we ran Carolina’s byline at the top, but want to acknowledge Luis as well for his contribution to this piece.

On Sunday, January 19 the Spanish newspaper El País had a first-page story titled “Los justicieros de Tierra Caliente,” giving long coverage to the recent autodefensa advances in Michoacán. Prominent in the article was a picture of a young woman posing with a rifle in one of the occupied houses of the Knights Templar’s leaders.

Its caption quoted a man identified as Comandante Cinco:

We want women to be at the very front. As you know the Knights Templar go after them. We want more armed women to be here, on the front.

Queremos que haya mujeres hasta adelante. Como saben, Los Templarios van por ellas. Queremos más mujeres que lleven armas y que estén aquí, al frente.

The quote and the image seemed to give a new perspective to the conflict, placing women at the forefront of the armed uprising. Yet a quick revision of the image gallery accompanying the article doesn’t show any other armed women. All other armed people are men. Women appear in the pictures as mourners, passersby, or demonstrating with placards. Also, upon closer inspection this particular image had a strange air to it. The young woman – more like a young teen – is posing inside of an occupied house, wearing mini-shorts and a tank top, attire not necessarily practical for a battlefront. This particular image’s apparent contradiction has led to its mocking on social media.

The article’s only other mention of women participating in the the uprising comes from this same commander a few paragraphs later:

gets a stack of bills and gives two to one of the women: “Go buy some things to clean the floor.”

saca un fajo de billetes y le entrega dos a una de las mujeres: “Vete a comprar cosas para limpiar el piso”.

This is definitely not an image of a fighting woman, is it?

Comandante Cinco’s assessment of violence against women is definitely correct. As a recent report by Anaiz Zamora Márquez indicates, women are both economic and sexual victims of the growing factional conflict in Michoacán. The article explains at some length the range of violence against women and calls for their protection. Yet the role of women as active defenders of their security or implementers of an alternative eludes the authors.

The El País piece concludes with a short profile of José Manuel Mireles, the Michoacán autodefensas leader. In it, he states that as violence grew the systematic rape of wives and daughters ultimately led him and others to create the movement. Mireles’ quote, comes from a longer video aired last June to explain the uprising’s reasons.

Llegaban a tocar a la puerta de las casas y decían: “me gusta mucho tu mujer, ahorita te la traigo, pero mientras me bañas a tu niña porque esa sí se va a quedar conmigo varios días’ y no te la regresaban hasta que estaba embarazada.

They knocked on your house’s door and said, “I really like your woman, I’ll bring her right back, meanwhile, bathe your daughter, because she will stay with me for several days.” And they didn’t return her until she was pregnant.

The Proceso article that embedded this video summarizes the uprising’s supposed trigger in its title: “Everything exploded when the narco abused our wives and daughters.” Mireles’ quote is very reminiscent of the opening pages of Mariano Azuela’s classic novel of the Mexican Revolution, Los de abajo, where the protagonist, Demetrio Macías, leaves his house to join the armed uprising when federal authorities enter his house and attempt to abuse his wife.

We have no question that violence against women remains a social curse. What we wonder, however, is where the armed fighting women are? And whether entering the political arena through armed autodefensas will address the curse?

Beyond Comandante Cinco’s broad generalization, little has been written about them, but a slow trickle is beginning. The Tierra del Narco blog published a short profile of the “Comandante bonita” (the Beautiful Commander), while El Universal published short profiles of her and two other fighting women, Idalia and “Dulcinea.”

The profiles cover these women’s contributions to the uprising, while also recognizing that “it isn’t easy; the hardest thing [being] struggling against people’s prejudices.” And yet, another aspect of these articles calls our attention: the emphasis on the fighters’ appearance and the questioning of their sexual relations with their companions in arms. Notes about their makeup, nail polish, and even the underwear they pack are central to the profiles. For example, Dulcinea (whose very name taken from Don Quixote evokes a male object of desire) is portrayed as a woman in love with one of the soldiers:

She is now in love with a young man from autodefensas; he has given her a stuffed cat which she carries with her to different camp sites. But not even her brother or boyfriend can take away certain solitude.

Ahora está enamorada de un joven de las autodefensas; él le ha regalado un gato de peluche que lleva a los diferentes campamentos. Pero ni el hermano ni el novio le quitan cierta soledad.

Just this Wednesday, La Jornada’s Facebook Page published a picture of two very glamorous women under the headline “Mujeres integrantes de las autodefensas de Tepalcatepec que hoy ‘tomaron’ el municipio de Los Reyes, Michoacán. Fotos Ignacio Juárez” (Women of the autodefensas of Tepalcatepec which today “took” the municipality of Los Reyes, Michoacán). Yet the linked article had no reference to women.

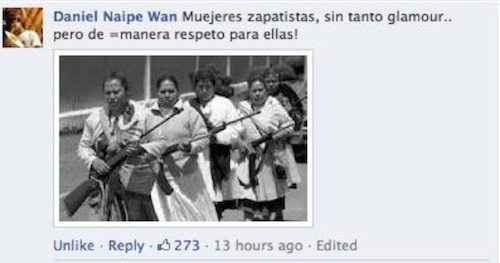

In reaction, one of the readers posted the following comment:

We asked women in Mexico for their views, focusing on how women in autodefensas are portrayed so far. On Twitter, the Mexican group “Luchadoras” expressed their support; “Here are three women who decided to join the struggle and are now facing social prejudice.” Regarding the emphasis on their looks and relationships, Luchadoras mentioned how “each one can freely construct their identity as they want.”

Tres mujeres que decidieron unirse a una lucha y se enfrentan a prejuicios sociales. Cada quien construya su identidad en libertad.

Mar Feminista added: “must they act masculine to get society’s approval and be brave?” (“Se deben masculinizar para obtener aprobación de la sociedad y ser valientes?”)

These views highlighted a question, how are women supposed to act to be respected inside autodefensas and in society? Is there a way out of the stereotypes associated with those women who choose to fight back? Although women’s freedom of choice is always supported, what if such media emphasis on their underwear, make-up, and reputation creates an opposite effect leading to unequal roles and incomplete representations?

The prejudice against women in autodefensa is supported by a cultural history of inequality. Las Soldaderas were women fighters who made significant contributions to both the federal and rebel armies of the Mexican Revolution. Yet, stereotypes of them as either “bad women” or submissive followers are common, according to a web page created by University of Michigan students Laura Norris and Joseph Reiss:

Because of the active role played by soldaderas in the Mexican Revolution, their legacy has contributed to several distinct stereotypes of Mexican women. Modern-day Chicanas in the United States have been particularly affected by this image of the soldaderas as either a feisty woman or promiscuous follower.

Like the soldaderas, the women in autodefensas are also stereotyped and, therefore, must work harder to fight social prejudices, both inside and outside autodefensas. They join men in battle but must remain feminine. They fight with autodefensas but must work on building a respectful reputation to avoid roles of “putas” or submissive followers.

In her testimonial novel Hasta no Verte Jesús Mío, Mexican writer Elena Poniatowska narrates the story of Jesusa Palancares, a soldadera who fights with men in the revolution. Palancares is seen as a “mala” (bad woman) by traditional society because she chooses to defend herself joining in the armed struggle instead of assuming a traditional role in the home:

De por sí, yo desde chica fui mala, así nací, terrible. Pero Pedro no me daba oportunidad. La bendita revolución me ayudó a desenvolverme. Cuando Pedro me colmó el plato ya me dije claramente: “me defiendo o que me mate de una vez.” Si yo no fuera mala, me hubiera dejado de Pedro hasta que me matara. Pero hubo un momento en que Dios me dijo: Defiéndete. (p. 101)

From the start, I was already bad, that’s how I was born, terrible. But Pedro never gave me the opportunity. This blessed revolution helped me develop my strength. When I had it with Pedro I told him clearly: “I will defend myself, or kill me at once.” If I were not bad, I would have let Pedro kill me. But there was a moment when God told me: Defend yourself.

Poniatowska, well known for capturing the reality of Mexican society, also gives us insight into the reality of women’s roles. Both in the times of soldaderas, and now with the women in autodefensas, women are yet to be framed in more complete, less prejudiced portraits. They are victims of violence and a vulnerable group, but when choosing to defend themselves, they are portrayed, not always, as equals. In this context, roles of Mexican women both outside and inside the autodefensas are to be further explored and recognized.

[…] Representing Women’s Roles in Michoacán Autodefensas […]

We are not denying http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan and we are not afraid http://yakuza4d.com confess, this war http://yakuza4d.com/home is our war and that it is waged for the liberation of Jewry…Stronger than all fronts “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar together is our front, that of Jewry. We are not only giving http://cintaberita.com this war our financial support on which the entire http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main war production is based. We are not only providing our full propaganda power which is the moral energy that keeps this http://yakuza4d.com/hasil war going. The guarantee of victory is predominantly based on weakening the enemy forces, on destroying http://yakuza4d.com/hasil them in their own country, within the resistance. And we are the Trojan Horses in the enemy’s fortress. http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi Thousands of http://www.cintaberita.com Jews living in Europe constitute the principal factor in the destruction of our enemy. There, our front is a fact and the most valuable aid for victory.