Cuando sonó la trompeta, estuvo

todo preparado en la tierra,

y Jehova repartió el mundo

a Coca-Cola Inc., Anaconda,

Ford Motors, y otras entidades:

la Compañía Frutera Inc.

se reservó lo más jugoso,

la costa central de mi tierra,

la dulce cintura de América.When the trumpet sounded

everything was prepared on earth,

and Jehovah gave the world

to Coca-Cola Inc., Anaconda,

Ford Motors, and other corporations.

The United Fruit Company

reserved for itself the most juicy

piece, the central coast of my world,

the delicate waist of America.—from “La United Fruit Co.” in Canto General (1950) by Pablo Neruda

This week, English-language media woke up to the shock that there is now a humanitarian crisis on the U.S.-Mexico border. Unaccompanied minors, mostly from Central America, are entering this country at record levels. Even President Obama addressed the crisis this past week. Granted, this news is not new news, but since the English-language mainstream is now involved, there is a sense of urgency.

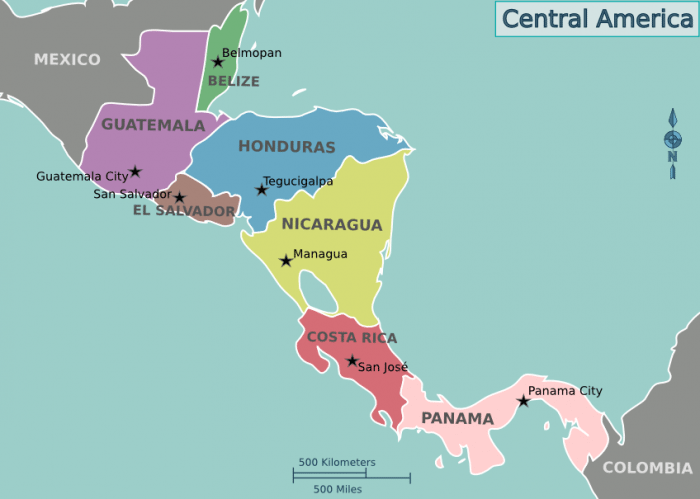

This is why immigration reform should pass, we are told. Look at these children. They are escaping hellish places, countries like El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras with “street gang epidemics, widespread organized crime and drug trafficking that place them among the world’s most violent places.” We are told that in Honduras “the murder rate is 90.4 homicides per 100,000 people — the highest in the world.”

What caused all this, people ask? How did this become such a crisis?

If we really want to answer that, we need to go beyond the headlines about Maras and begin to examine the truth: the United States created this situation in Central America, and now it must find a way to deal with it.

Yes, before discussing present-day causes, we must first explore history. Now the easy example is to just download the following macro view of U.S. interventions in Latin America since 1846 and end this piece right here. Every decision to meddle has lasting consequences.

Here is just one example:

Very few could argue that the United States’ “Monroe Doctrine” mentality has not played a negative role in Latin America. The moment President James Monroe declared this in 1823 —“American continents, by the free and independent condition which they have assumed and maintain, are henceforth not to be considered as subjects for future colonization by any European powers”— the United States would forever directly influence Latin America. Add the fact that these former European colonies were all modeled on a system of elites who controlled the wealth, and the U.S. was primed to literally own its backyard by ignoring democratic principles and work with a small group of local leaders who placed power and greed above all. Let’s not fool ourselves one bit. The history (and tragedy) of post-colonial Latin America has always had the U.S. as part of its core.

Such is the case of Central America, which was actually a federation before it became what it is today. (Imagine if it had remained a larger country?) The U.S. has been involved in the history of that region since 1824. Soon the federation broke up due to civil war, and before you know it, bananas came back to U.S. around 1870 and the history of the region changed dramatically.

As The Economist wrote last year about “banana republics:”

[The term “banana republics”] was coined in a 1904 book of fiction by O. Henry, an American writer. Henry (whose real name was William Sydney Porter) was on the run from Texan authorities, who had charged him with embezzlement. He fled first to New Orleans and then to Honduras where, staying in a cheap hotel, he wrote “Cabbages and Kings”, a collection of short stories. One, “The Admiral”, was set in the fictional land of Anchuria, a “small, maritime banana republic”. It is clear that the steamy, dysfunctional Latin republic he described is based on Honduras, his jungle hideaway. Henry eventually returned to the United States, where he spent time in prison before publishing his short stories and then hitting the bottle, leading to an early death. – See more at:

His phrase neatly conjures up the image of a tropical, agrarian country. But its real meaning is sharper: it refers to the fruit companies from the United States that came to exert extraordinary influence over the politics of Honduras and its neighbours. By the end of the 19th century, Americans had grown sick of trying to grow fruit in their own chilly country. It was sweeter and cheaper by far to import it instead from the warmer climes of Central America, where bananas and other fruit grow quickly. Giants such as the United Fruit Company —an ancestor of Chiquita— moved in and built roads, ports and railways in return for land. In 1911 the Cuyamel Fruit Company, another American firm (which was later bought by United), supplied the weapons for a coup against the government of Honduras, and prospered under the newly installed president. In 1954 America’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) backed a coup against the government of Guatemala, which had threatened the interests of United. (Historians still debate whether the CIA’s motive was to protect United or, as many now believe, to nip Communism in the bud.) Hence the real meaning of a “banana republic”: a country in which foreign enterprises push the government around.

Even those who question the influence of U.S. companies in Central America (see “The Banana Republic: The Myth of the United Fruit Company”) and say that these companies help to benefit Central America’s economic development, still conclude that “The mythic United Fruit Company left its mark on Latin America and the world through their immense power and notorious actions in overturning leaders.”

It is a cycle that has repeated itself and came to a blow when U.S policies of the late 70s and 80s led to one of the darkest times in Central America. As this section from a June 2 CBS News report so aptly explains:

Doug Massey, a sociology professor at Princeton University, traces the rise in Central American migration back to U.S.-Contra intervention in Central America in the 1980s as a way to ward off communist influence in the region. It also led to lasting instability in countries including Honduras, Guatemala and El Salvador

“It was really driven initially by cohorts that left Central America in the ’70s and ’80s because of the violence,” Massey said in an interview with CBS News. “What we’re seeing now is the long-term consequences of that with people trying to unite with their families north of the border where they can’t return.”

His research found very little migration from Central America prior to 1980, followed by an uptick in the 1980s and 1990s. In the mid-2000s, the number of apprehensions and deportations of Central American immigrants from Nicaragua, El Salvador and Guatemala soared to more than 150,000 even as it remained close to zero among nations where the U.S. had not intervened, like Costa Rica, Panama and Belize as enforcement along the border tightened and deportations were increased.

Many immigrants who might have returned to visit or stay their home countries chose to stay in the U.S. because it became so much harder to return, he said.

In addition, the new “bananas” have become narcotics. Americans love their drugs, too, and there is money to be made. Such demand, mixed with instability and violence have indeed played a role in the “merry go-around” of the Maras. The following excerpt is from a 2005 LA Times story:

In the last 12 years, U.S. immigration authorities have logged more than 50,000 deportations of immigrants with criminal records to Central America, including untold numbers of gang members like Cruz-Mendoza.

But a deportation policy aimed in part at breaking up a Los Angeles street gang has backfired and helped spread it across Central America and back into other parts of the United States. Newly organized cells in El Salvador have returned to establish strongholds in metropolitan Washington, D.C., and other U.S. cities. Prisons in El Salvador have become nerve centers, authorities say, where deported leaders from Los Angeles communicate with gang cliques across the United States.

That was in 2005. Nine years later, those who live in Central America are paying the price for a humanitarian crisis enabled by the U.S.

History and economics cannot be overlooked. However, all of a sudden, we are appalled to see unaccompanied kids entering this country by the thousands.

It is all connected, and maybe when the U.S. stops following an arrogant policy formed in the 19th century and starts realizing that the 21st century is more about being a better neighbor, then this crisis will vanish, and children can live in peace. Stopping the consequences of close to 200 years of history can’t happen in weeks. The U.S. must make stronger and positive commitments to Central America. It caused the problem, now it needs to fix it.

***

EDITOR’S NOTE: Julio (Julito) Ricardo Varela (@julito77) founded LatinoRebels.com in May, 2011 and proceeded to open it up to about 20 like-minded Rebeldes. His personal blog, juliorvarela.com, has been active since 2008 and is widely read in Puerto Rico and beyond. He pens columns on LR regularly. In the last two years, Julito represented the Rebeldes on CBS’ Face the Nation, NPR, Univision, and The New York Times. Recently, he was a digital producer for Al Jazeera America’s The Stream.

[…] all kinds of human dangers than the already hellish conditions in their home countries, conditions supported and oftentimes designed by the very same government now trying to remedy an “urgent humanitarian […]

[…] all kinds of human dangers than the already hellish conditions in their home countries, conditions supported and oftentimes designed by the very same government now trying to remedy an “urgent humanitarian […]

[…] all kinds of human dangers than the already hellish conditions in their home countries, conditions supported and oftentimes designed by the very same government now trying to remedy an “urgent humanitarian […]

[…] Ricardo. “Humanitarian Crisis of Migrant Children Confirms US Failure in Central America,” Latino Rebels, June 7, […]

[…] we’re going to discuss the root causes of the current Honduran refugee crisis, let’s get a few things […]

[…] we’re going to discuss the root causes of the current Honduran refugee crisis, let’s get a few things […]

[…] we’re going to discuss the root causes of the current Honduran refugee crisis, let’s get a few things […]