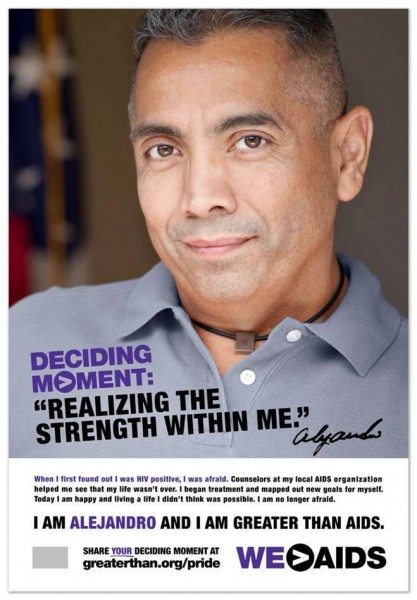

During my travels and with many different endeavors, I have the privilege of meeting several bright and charismatic leaders from across the globe. As someone who has dedicated his life to developing positive, social change in a society where quantifiable progress comes slowly, we as Latinos often become tired of fighting, resisting and advocating for our issues on a daily basis. For me, connecting and sharing stories with others is a source of renewal and revitalization, which is what happened on the day I connected with Alejandro Lopez.

The Latino experience is pluralistic: we as a people are diverse and have several different stories. As Latinos, we can easily find ways to connect but we also justify our reasoning for disunion. We explore reasons to build each other up and tear each other down. When I first came across Alejandro, he asked me if I’d be interested in helping tell his story. Initially I wondered what his story might entail. After our initial discussions, I realized Alejandro’s story carried a heavy and complex account of abuse, discrimination and affliction.

First, let me say that this story contains materials that might be disturbing to some readers. As a rebel with a machete pen, I want to confront the issues —the good and the bad— that we as a people struggle with, in addition to collectively provide suggestions to solve our problems. Furthermore, we need to look to each other for hope, assistance and kinship. Let us be each other’s keeper.

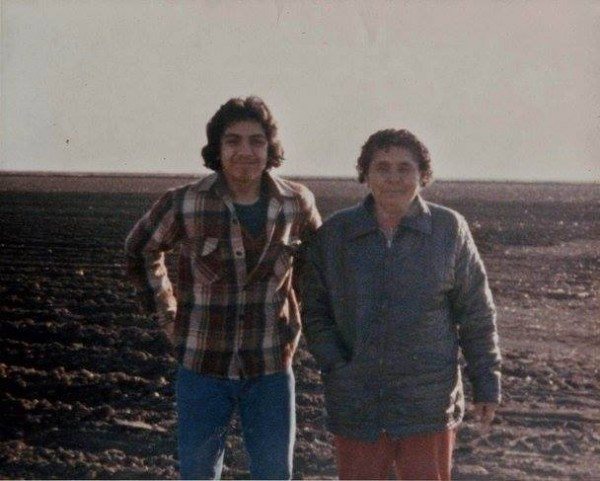

Alejandro Lopez is originally from Laredo, Texas. Like many Tejanos, a young Alejandro lived the life of a migrant worker in Hereford. This arduous lifestyle consisted of going to school, working the onion fields until sunset, finishing homework, then doing it all over again the next day. As a young man exploring his identity, Alejandro realized he was bisexual. It was also during this time that a couple members of his family became sexually abusive to Alejandro. With this self-realization and in an abusive situation, with his own father threatened to kill him for being a “pendejo joto,” Alejandro’s mother urged him to move away. Alejandro felt as if he didn’t have a lot of options, so in 1984 after high school, he joined the Army.

Alejandro went on to serve his country in the 307th medical battalion, 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, NC. While in the military, Alejandro began having an intimate relationship with a fellow male soldier. At this time, before “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” homosexuality in the military was illegal and highly frowned upon. While it was something that wasn’t openly discussed, it was known that there were several people in the Army that were gay. In the early 80s, with the boom of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, testing became more prevalent. One day, while on the job in the military as a personnel administrative specialist, Alejandro became privy to sensitive information that 17 people tested positive for HIV. One of the 17 names on this list was the soldier Alejandro had been with.

During the next few years, many of Alejandro’s friends began to die due to complications with HIV/AIDS. A spiteful, ex-boyfriend called Alejandro’s first sergeant and “outed” him. This began a covert investigation where an undercover agent tracked Alejandro and eventually confronted him with the question, “Are you a faggot?” In 1989, under the discretion of his first sergeant, Alejandro was honorably discharged after serving for close to six years—Alejandro had been kicked out of the U.S. Army.

With nowhere to go, Alejandro began working in Fayetteville, North Carolina. His ex-partner began stalking him. Again, finding himself at a crossroads, Alejandro dropped everything and moved back to Texas with $200 that his mother sent him.

Alejandro soon found himself again in the center of a familial dispute. After a state audit, it came to light that his parents had not received the correct of amount of money due back to them from Social Security. A $23,000 backpay was due to the family for all of the years they worked. The family became at odds over what to do with the money. Alejandro sided with his mother, who was becoming more in need due to her ailing health. She was always there to support Alejandro and he was returning the favor.

Also, Alejandro regularly donated blood. In 1993, Alejandro received a phone call from the blood bank stating that they’d like to meet with him. This dreaded phone call and the subsequent meeting is one that no one wants to receive. Alejandro only remembers two sentences from the meeting: “You have tested positive for the HIV virus. There is no cure for this.” Unbeknownst to Alejandro at the time, the HIV virus can thrive in your system for 10 years without showing any signs or symptoms. Eight years after being exposed to the virus, Alejandro finally tested positive. About a month later, it finally hit Alejandro. He said, “I’ve got the virus!” At this point, not many people knew he was gay. Almost all of the people he was open with weren’t around anymore. Still, Alejandro was preparing for a battle of losing his mother.

Alejandro’s mother was aging and struggling with her diabetes condition. Both of her legs were amputated. With no one taking care of her, Alejandro declared he was going to move his mother out of the house. Alejandro’s sister agreed to take in his mother and nurse her. Alejandro’s mother would often have to throw herself out of bed in order to shower or use the restroom. The final straw was when the police gave her a courtesy ride to the pharmacy, to fill a prescription, because no one else would. Alejandro always had a place in his heart for his mother because she was there to console him during his times of need. He confided with her about his condition. A year and a half later, Alejandro’s mother passed away. Her last wish was that Alejandro not tell their family that he was HIV positive.

One year later, two of Alejandro’s young nieces were abducted by a man who disguised himself as a police officer. The same day the town little girls were found beat up. One was nearly choked to death and the other was raped and ran over with a truck. Close to five hours of surgery were needed in order to repair her fractured skull and collapsed lung. With all of these events, in addition to Alejandro’s condition, he became highly depressed.

He didn’t want to go anywhere or do anything.

He was dying inside.

At the age of 27, he didn’t know if he’d see 30.

In 1996, he went to a retreat for HIV positive men and women. Alejandro met Joe and the two started dating for seven months. Joe passed away in May of 1997 due to HIV/AIDS complications. Alejandro felt as if Joe was the first person he ever cared about. This man was the love of his life, and Alejandro could finally be himself openly. Again, depression began to sink in. With more loss surrounding Alejandro, just when things were starting to turn around, how could he recover? Alejandro thought suicide might have been the answer. One day a neighbor came to Alejandro and helped him realize the positive things in his life. Reflecting on his past, Alejandro realized that his health care and benefits were covered from his military experience. Had his first sergeant discharged Alejandro dishonorably, he would not have had this coverage and may have easily died without access to treatment. Slowly gaining strength and a positive mindset, Alejandro began living the life he had for himself. While still working for Walmart, Alejandro put in for a transfer from Amarillo, Texas, to Georgia. He started his new life in 1997.

Alejandro found a law firm that has accepted him for who he is and they hired him to a full-time position in Atlanta. It would not have been uncommon for any organization or business to discriminate Alejandro due to his sexuality or health conditions. Alejandro now is also a board member for Georgia Equality, an LGBT advocacy group that promotes fairness, safety and opportunity for LGBT Georgians. Alejandro’s past experiences fuel his drive to fight for the causes that have affected him; he’s an advocate for health and wellness in the LGBT community as a navigator of the Affordable Care Act and Latino outreach. Alejandro knows about advocacy and is still fighting for his own life.

Alejandro is preparing to go through his second attempt of eliminating Hepatitis C from his system. The first treatment included two shots a week with side effects of intense cold feelings, vomiting and weight loss. A new treatment may affect him differently. In April of 2015, he’ll start a new treatment, which will probably bring on new side effects and not guarantee his health. He’s also receiving medication for HIV, which include him taking seven pills a day. The maintenance of these meds is lengthy. This is a far cry from the earlier years treatment of AZT, DDI and DDT, plus the Bacterim he used to take, which added up to 23 pills a day at various hours of the day.

It took Alejandro a long time to find the strength to disclose his condition and trust others. But he finally realized his worth; his value and that his condition doesn’t limit what he can do. Alejandro feels fortunate for where he is in life and is thankful that the good Lord has saved him. Today, Alejandro lives happily by the saying, “Living with HIV doesn’t define who I am.”

One may question why highlight a story such as this one. In actuality, these are the current realities, stories, and lives we lead. While many of us live advantageous and fortuitous lives, there are several others dealing with troubles that go deep beyond the surface. And for those of us currently experiencing troubling times, what mechanisms do we use to turn things around? There’s an estimated 220,000 Latinos living in the United States with HIV/AIDS; although we make up 16% of the current U.S. population, we account for 21% of new HIV infections. Millions more struggle with depression, addiction, and family problems. Furthermore, the HIV/AIDS epidemic is not something exclusive to the LGBT community; we often ignore the problem outright in heterosexual lifestyles. HIV/AIDS, like familial problems, is often taboo in many circles. Why do we turn a blind eye? Why do we accept that some things and fight to change others? We as a people are a resilient nation; the tragedies we experience are a shared experience. And we must do better with regards to our own health, individual decision-making, and acceptance of others. If we don’t, we’ll perish by our own swords. It is my hope that this article will encourage us all to have open dialogue on the issues that plague our communities: conditions of migrant workers, machismo, homophobia, diabetes, mental health stability, safe intimate relations, and the unwillingness to seek help. There are organizations like Georgia Equality that can assist us in times of need. And we can’t be afraid to seek that help. In the end, we’re all people and when we collective see ourselves as Brothers & Sisters of the same struggle, we’ll grasp our true place in society as a force to be reckoned with.

In the spirit of positivity and wellness.

***

Máximo Anguiano is a creative and public intellectual from San Antonio, TX. Follow him on Twitter or Facebook.

Truthfully, i was tested HIV + positive last 3years. I keep on managing the drugs i usually purchase from the health care agency to keep me healthy and strengthen, i tried all i can too make this disease leave me alone, but unfortunately, it keep on eating up my life, this is what i caused myself, for allowing my fiance make sex to me insecurely without protection, although i never knew he is HIV positive. So last few 4days i came in contact with a lively article on the internet on how this Powerful Herb Healer get her well and healed. So as a patient i knew this will took my life 1 day, and i need to live with other friends and relatives too. So i copied out the Dr drahmed the traditional healer’s email id: drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com and I mailed him immediately, in a little while he mail me back that i was welcome to his temple home were by all what i seek for are granted. I was please at that time. And i continue with him, he took some few details from me and told me that he shall get back to me as soon as he is through with my work. I was very happy as heard that from him. So Yesterday, as i was just coming from my friends house, Dr drahmed called me to go for checkup in the hospital and see his marvelous work that it is now HIV negative, i was very glad to hear that from him, so i quickly rush down to the nearest hospital to found out, only to hear from my hospital doctor called Browning Lewis that i am now HIV NEGATIVE. I jump up at him with the test note, he ask me how does it happen and i recede to him all i went through with Dr drahmed I am now glad, so i am a gentle type of person that need to share this testimonies to everyone who seek for healing, because once you get calm and quiet, so the disease get to finish your life off. So i will advice you contact him today for your healing at the above details: Email drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com or call him on +2348147326843

MY HIV HEALING TESTIMONY

My mouth is short of words, i am so so happy because Dr.Ahmed

has healed me from HIV ailment which i have been suffering from the

past 5years now, i have spend alot when getting drugs from the

hospital to keep me healthy, i have tried all means in life to always make sure i can become Hiv negative one day, but there was no answer until i

found Dr from Dr.Ahmed the paris of african who provide me some

healing spell that he uses to help me, now i am glad telling everyone

that i am now HIV Negative, i am very very happy, thank you Dr.Ahmed

for helping my life comes back newly without anyform of crisis, may

the good lord that i serve bless you Dr.Ahmed and equip you to the

higher grade for healing my life. i am so amazed. so i will announced

to everyone in this whole world that is HIV positive to please follow

my advice and get healed on time, because we all knows that HIV

disease is a deadly type,contact Dr.Ahmed for your Hiv healing spell

today at: drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com…. He will be always happy to

assist you online and ensure you get healed on time, contact Dr.Ahmed

today for your healing spell immediately, thank you sir:

drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com call +2348147326843

I will says to the world to celebrate this great testimony with me, i never believe i can eve get rid of these horrible disease one day. My story and thanksgiving goes to Dr AHMED the powerful man who help me to CURE MY HIV/AIDS disease from my life. I don’t know how to say this to everyone, Dr AHMED is a truthful man with high herbs power’s he uses to save people’s life. Last few days i came in contact with Dr AHMED emails on the internet which people gave much testimonies about his kind fullness work. So i decided to contact him quickly because this disease was almost on the last step of taking my life from me. I have tried all my best in life to get heal but nobody could ever help apart from Dr AHMED who finally help me to cure my HIV disease from me. I always amazed and overwhelmed when the doctor confirm that i am now healed from aids, and now, i am an HIV/AIDS NEGATIVE PATIENT. I wish anyone who is sick today and wants a healing please i will kindly advice you to contact this man called Dr AHMED now at: drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com To get this powerful healer full article and trust on his origination and references please visit him now again at: I will says to the world to celebrate this great testimony with me, i never believe i can eve get rid of these horrible disease one day. My story and thanksgiving goes to Dr AHMED the powerful man who help me to CURE MY HIV/AIDS disease from my life. I don’t know how to say this to everyone,Dr AHMED is a truthful man with high herbs power’s he uses to save people’s life. Last few days i came in contact with Dr AHMED emails on the internet which people gave much testimonies about his kind fullness work. So i decided to contact him quickly because this disease was almost on the last step of taking my life from me. I have tried all my best in life to get heal but nobody could ever help apart from Dr AHMED who finally help me to cure my HIV disease from me. I always amazed and overwhelmed when the doctor confirm that i am now healed from aids, and now, i am an HIV/AIDS NEGATIVE PATIENT. I wish anyone who is sick today and wants a healing please i will kindly advice you to contact this man called Dr AHMED now at: drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com

To get this powerful healer full article and trust on his origination and references please visit him now again at: drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com or you can contact his phone number +2348147326843

Contacting dr ahmed is probably one of the best thing that has ever happened to me.I believe every one has his or her option about spell.You may have the impression that its real and others may think spells are for the deranged.For me, i think its doesn’t matter what you think or what you know about spell because we both know humans seek solution where ever there is one even if it means believing in something they find to insanely not true.I guess for me i believed in what could help me get full custody of my boys after my marriage fell as a result of my drinking addiction.I once use to drink a lot, my husband was not strong enough to walk through the storm with me.Like he said i ruined our marriage.You know its always goes the same with all men when you need them the most in times of trouble they run as far as possible from you and justify their infidelity based on your wrong doing.While i was getting help my husband was banging our neighbor she was a single mom so it was a good catch for him.she single with three kids and he had a wife who was addicted to drinking it was the perfect match.Maybe if he had done it once out of weakness and was sorry about it we will still be together but no he kept on with it.I don’t really blame anybody but myself i was not around and she was there for him.I had drinking problem and she didn’t so i was more of a problem to him that i was a wife i think.I am one year sober now, even at that he still treat me like the drunk i was restricting me from seeing my boys.Like he said i am a bad influence and danger to them.I mean i was sober and still he prevented me from seeing my kids.I understand that he didn’t love me anymore cos yeah he found a more virtuous woman than i ever was and see had to sort of addiction even at that, i was still the mother of my kids and no matter what that is not going to change.Maybe my drinking problem was a contributing factor to our failed marriage or he never loved me that much to wait or hold my hand through the storm either which that is so not enough use my addiction as a medium to prevent me from seeing my kids i mean ever kid need the love of their mother.I was never capable of hurting my kids before i had my addiction and my kids, where the reason i seeked for help so now am sober i don’t see myself as a threat or a bad influence to upbringing of my kids.Before i ever thought of resolving to spell casting i thought about involving the law but my lawyer was so sure that my ex lawyers would have been able to easily convince the judges that i am a threat to my kid and that my addiction can kick in anytime i feel pressured again cos that was the root of my addiction.I don’t think anybody a man or a woman, can handle not being able to see their kids just cos you were once an addict of any sort.I was sad, confused and out of options.when i was served the divorce papers my kids custody was brought into the picture again.I realized that i was going to lost my boys forever.No mother wants another woman to raise their kid it was also the same for me i could not think of it at all.Maybe the law may have allowed me to see my them, it will would have been based on how and when its convenient for my ex to want me to go see them and also under his supervision.Either ways i was the loser but thank god i found dr ahmed as silly as it might be, he helped me cast a spell that gave me full custody of my kids.It wasn’t the law that was compelled to give me custody, it was my ex the spell compelled.He asked is lawyers to tell the judge that he wants me to have full custody of our kids. dr ahmed doesn’t ask anyone for money all he ask for are materials to for the spell casting process.And even that you can get them yourself and send them to him.My experience with him even if i never got to meet him, was an experience that will last for ever cos if not for the spell he helped me with i would still in search for a way to get to see my kids.If you really want to contact him use this email drahmedhealinghome@gmail.com com hopefully he can help you resolve what ever problem you bring before him and his god or gods which ever.

Greetings to you all, i am here today on this forum giving a life testimony on how prophet suleman has cured me from HIV Virus, i have been stocked in bondage with this virus for almost 2years now, i have tried different means to get this sickness out of my body i also heard there was no cure to the virus, all the possible ways i tried did not work out for me, i do have the faith that i was going to be cured one day, as i was a strong believer in God and also in miracles, One day as i was on the internet i came across some amazing testimonies concerning how prophet suleman has cured different people from various sickness with his Herbal Herbs Medicine, they all advised we contact prophet suleman for any problem, with that i had the courage and i contacted prophet suleman i told him about my Sickness, He told me not to worry that he was going to prepare some Herbal Medicine for me, after some time in communication with prophet suleman , he finally prepared for me some herbs which he sent to me and he also gave me prescriptions on how to take them, My good friends after taking prophet suleman Herbs for some weeks i started to experience changes me and from there, I noticed my Herpes Virus was no longer in my body, as i have also gone for test, Today i am fit and healthy to live life again, I am so happy for the good work of prophet suleman in my life, Friends if you are having any time of disease problem kindly email prophet suleman on { prophetsuleman@hotmail.com} God Bless you Sir……………sellina

Greetings to you all, i am here today on this forum giving a life testimony on how prophet suleman has cured me from HIV Virus, i have been stocked in bondage with this virus for almost 2years now, i have tried different means to get this sickness out of my body i also heard there was no cure to the virus, all the possible ways i tried did not work out for me, i do have the faith that i was going to be cured one day, as i was a strong believer in God and also in miracles, One day as i was on the internet i came across some amazing testimonies concerning how prophet suleman has cured different people from various sickness with his Herbal Herbs Medicine, they all advised we contact prophet suleman for any problem, with that i had the courage and i contacted prophet suleman i told him about my Sickness, He told me not to worry that he was going to prepare some Herbal Medicine for me, after some time in communication with prophet suleman , he finally prepared for me some herbs which he sent to me and he also gave me prescriptions on how to take them, My good friends after taking prophet suleman Herbs for some weeks i started to experience changes me and from there, I noticed my Herpes Virus was no longer in my body, as i have also gone for test, Today i am fit and healthy to live life again, I am so happy for the good work of prophet suleman in my life, Friends if you are having any time of disease problem kindly email prophet suleman on { prophetsuleman@hotmail.com} God Bless you Sir………….sellina

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.