Puerto Ricans are the most marginalized citizens in the United States, and that goes double for members of the Puerto Rican diaspora. Mainland Puerto Ricans are often denied the right to speak about the issues affecting an island whose inhabitants are denied the right to decide their own issues to begin with. When mainlanders say they support Puerto Rican independence, some islanders are quick to tell that it’s none of their business. It’s easy for you mainlanders to support independence from the enfranchised comfort of Illinois, New York or Florida, they argue.

While a person with rights can only vaguely imagine what it’s like for a person who has none, that I was born and raised on the mainland shouldn’t preclude me from any debate concerning my ancestral homeland. After all, it isn’t my fault that I was born a Chicagoan and not a Ponceño.

I am here because the United States is there.

Judging by the countless errors committed by the island’s political establishment, nothing in the air endows someone born in Puerto Rico with special knowledge of the past and present. The same is true of any place on earth. You don’t have to be a born and bred Cuban, for instance, to see that intransigence in both Havana and Washington has hobbled the Revolution. You don’t have to have been born in the hills outside Tegucigalpa (as my mother was) to know what greed and corrupt has done and continues to do to the people of Honduras. You don’t need a Caracas address to realize chavismo must die if bolivarianismo is to succeed.

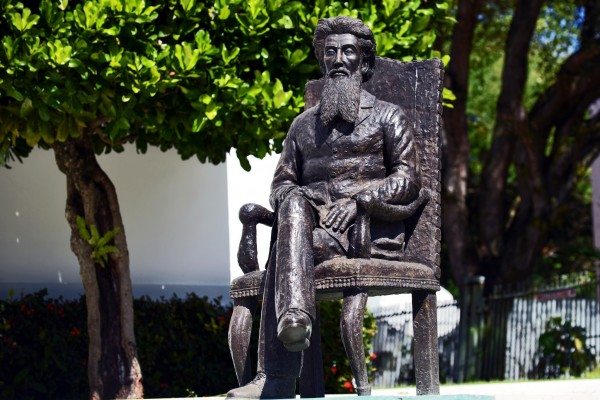

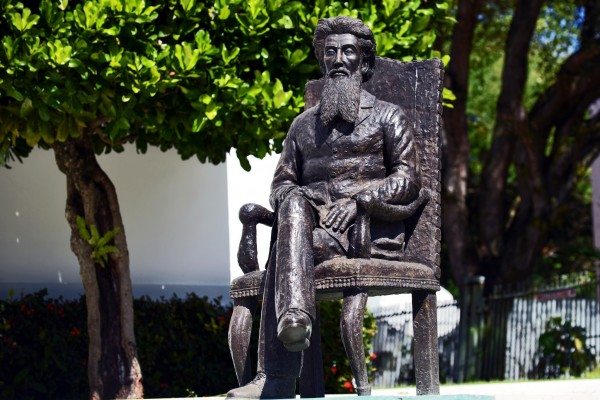

With more Puerto Ricans living off the island than on it, the nation of Puerto Rico covers more than a few thousand square miles of land. It has always been that way. When Betances and Ruiz Belvis formed the clandestine group that would launch the Grito de Lares in 1868, they did it from the safety of New York. And when the Puerto Rican Revolutionary Committee adopted the current flag of Puerto Rico in 1895, again they did it not in Puerto Rico, but on the mainland.

Statue of Ramón Emeterio Betances by the Dominican sculptor José Cadaveda at the Ateneo Puertorriqueño (Credit: Harvey Barrison/Flickr)

They were here because the colonizer was there.

Betances only became an independentista after he left Puerto Rico to study in Paris, just as Don Pedro Albizu Campos would become an independentista after leaving the island to study at Harvard half a century later. (Cosmopolitan experiences are common in the revolutionary history of the Americas, from Paine and Bolívar to Che and Baldwin.) Their identity as citizens of the world, or at least their solidarity with the struggles of other peoples, informed and galvanized their support for Puerto Rican independence.

The Nuyorican poets have no less to say about puertorriquenidad just because they weren’t born in Puerto Rico. Being born on the mainland doesn’t mean the “war against all Puerto Ricans” never took place.

As young and removed as I am, being a Chicago-born Boricua Millennial, most of the criticism I receive for my pro-independence writings is directed not at my facts, but at my motives. Nearly every critic tends to agree with my portrayal of Puerto Rico as a centuries-old island colony sinking ever deeper into the sea under the crushing weight of Lady Liberty’s freedom-loving sandal. Most admit American democracy doesn’t grant Puerto Ricans the tools to build their own futures. They only resent that anyone not living on the island would care or add anything to the very critical discussions taking place at the moment.

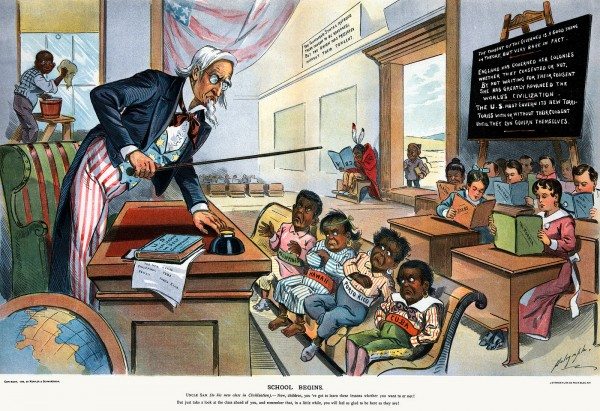

My puertorriqueñidad has little to do with my knowledge of Puerto Rico and its history. Having a Puerto Rican father and a point of origin in Puerto Rican Humboldt Park merely put the island and its people in front of my nose. That I was of the island genealogically made me want to know something about it. But what makes me write so emphatically in favor of Puerto Rican independence is that I am an American, politically and culturally speaking, and as an American, I was raised with a certain reverence for words like liberty, equality and justice.

Admittedly, for the system that taught me such words, they are nothing more than ink—slogans designed to give people of my caste the impression that they live in a society which upholds the loftiest of ideals. The joke is on the system, however, for my natural curiosity led me to study the ideas behind those words, and now I’ve come to appreciate them all the more.

Fitted with this appreciation, I look around the world and see places where liberty, equality and justice are rarely spoken. One of those places happens to be where my father’s parents were born and raised. It also happens to be the land where my government’s flag was planted long ago, back when my father’s parent’s parents were only children.

I care about there because I have learned about rights here, and I write about there because my government is there.

The United States won’t grant statehood to the island anytime soon, and since it won’t, it must grant Puerto Rico its independence. I can say that as an American, but I can know that as a person and a citizen of the world. You don’t have to have been raised in the shadow of El Yunque to know that the island cannot float, half state and half free. And just as an abolitionist cannot tell a slave what to do with her life after she’s freed, my authority to discuss Puerto Rican politics will end the day Puerto Rico gains its independence.

Until then I will care, and I will write.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is a Chicago-based writer. He is also Latino Rebels’ Deputy Publisher. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.