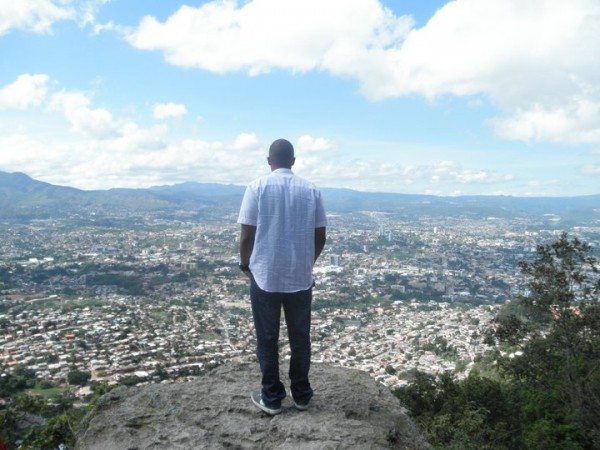

Santa Lucia, Honduras (Nan Palmero/Flickr)

Whenever my family gathered for Thanksgiving —the the chief holiday on my family’s calendar— my grandmother regaled us, especially her grandchildren, with tales from the old country: the place where she, my mother and my aunts were born. The setting of her stories was always Santa Lucía, which, having piece together the details from a couple dozen stories, I knew was a village tucked in the verdant hills not far from a capital city named Tegucigalpa. Long before I ever heard of Macondo, my grandmother —the matriarch whom everyone referred to as “doña Blanca,” but whom I simply called “Ita“— described a world of farmers and miners, of barefoot kids using rocks as dolls, of rumors of buried treasure and curses, of witches who morphed into pigs or owls, of a misty lagoon beyond which lay an sinister forest where kids dared not enter. It wasn’t until I was in middle school that I learned Santa Lucía is in a country named Honduras, in a part of the world known as Central America.

And it wasn’t until the age of 25 that I got the opportunity to visit the land about which I felt I already knew so much, and with the very same woman who had taught it all to me. This was in 2011, two years after the Honduran president was taken from the palacio in the dead of night and illegally flown to Costa Rica from a U.S. airbase. We arrived a mere two days after the deposed president had returned from exile. Militarized police personnel carried automatic rifles in every city I visited, from la costa to la capital. Anti-government graffiti adorned the façades of many buildings. Everyone warily eyed everyone else, and people spoke in hushed tones.

Now whenever I try to update my grandmother on what’s going on in Honduras —the gang violence, the government repression and corruption— she won’t hear any of it. “The journalists are trying to show Honduras in a bad light,” she insists. “Did you see anything bad when we were in Honduras?”

She supported the coup, believing the official line that President Mel Zelaya was a crypto-socialist sidling up to Hugo Chávez in Venezuela and the Castro brothers in Cuba, only half of which is true. While Zelaya did nearly double the minimum wage and planned to redistribute land seized by Honduras’s domineering agribusinesses, such actions were not so much socialist as they were an attempt to kickstart the free market, a goal in line with the centrist Liberal Party whose ticket Zelaya was elected on back in 2005.

Still, my grandmother no longer speaks of Honduras as enthusiastically as she once did. It could be that she never did to begin with and that, as I’ve matured, I’ve learned to recognize the look of dolor on a person’s face. Nonetheless, her expression sinks whenever mention is made of the homeland, and hearing the national anthem will reduce her to tears on the spot. Whether hers are tears of joy or sadness, I’m not sure, though I assume it’s a bit of both.

According to a recent estimate, there are over 700,000 Hondurans in the United States, making up less than two percent of the Latino population. Even that figure seems too high. I can probably count the number of Honduran Americans I know, not in my own family, on both hands. By comparison, there are over 30 million Mexicans in the United States, and the five million Puerto Ricans living in this country outnumber of the combined populations of Guatemalans, Hondurans, Salvadorans, Nicaraguans and Costa Ricans.

Flag of the Federal Republic of Central America, 1823-1838 (Wikimedia)

I named these countries specifically because these are the ones celebrating their independence today. It was on this day in 1821 that the Act of Independence of Central America —organized in Guatemala City by delegates representing what would become Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua and Costa Rica— was enacted. It was these countries that would break away from the Mexican Empire in 1823 to form the United Provinces of Central America, the five-member republic memorialized by the five stars on the Honduran flag. These countries, because they declared their independence collectively —Belize was then a British colony, and Panamá had declared its independence 11 years earlier as part of the South American republic of Gran Colombia— constitute the narrowest definition of Central America.

Perhaps because the Honduran American population is so small, or maybe because the histories of Central America are so interwoven, I tend to feel as much Central American as I do Honduran. Crisis breeds solidarity, and over a century of imperialism, beggary and political tumult have created a bond amongst Central America rivaled only by the one amongst the veterans of a hard war or the survivors of some catastrophe. The term centroamericano carries a meaning that the leaders of the European Union wish European enjoyed, a sense of kinship similar to that of African. My fellow Central Americans understand, I hope, that the region as a whole could be greater —and safer— than its individual parts have been. That is the dream, anyway.

Today the countries of Central America, especially those of the so-called Northern Triangle —Guatemala, El Salvador and Honduras— are beleaguered as ever. Guatemala is in the midst of a corruption scandal that forced the resignation of its president, a former general suspected of committing crimes against humanity during the country’s 36-year civil war. While the people of El Salvador experiment with progressive reforms under their second leftist presidency in a row, gang violence threatens to suck up all of their time, energy and will power. The coup regime in Honduras has just entered its sixth year, and an even larger corruption scandal than that of Guatemala plus violent state repression have placed Hondurans on the road to either revolution or tyranny. Communism has turned Nicaragua into another Venezuela, though without the oil reserves. And Costa Rica, long the most peaceful of the Central American republics, is beginning to see an infiltration of the same gangs which are leaving the gutters in San Salvador and San Pedro Sula running with blood.

The people of Central America have struggled to maintain their independence ever since it was declared nearly two centuries. They’ve seen whatever little hope they had shattered time and again by brutal gangs, crooked leaders, rapacious companies and a seemingly all-powerful hegemon. Rarely has the region been left to its own devices and allowed to shape its own destiny. For Central Americans, democracy is a promised land somewhere over the mountains or on the other side of a wide and raging river.

In the midst of the chaos, in 2007 the United Nations threw salt in the wound —perhaps unwittingly, perhaps not— by establishing its own observance on September 15. While today Central Americans will reflect on what could have been, the rest of the world will be celebrating the International Day of Democracy.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is a Chicago-based writer and the deputy editor at Latino Rebels. You can connect with him @HectorLuisAlamo.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.