Editor’s Note: An original version of this piece was published here. The author has granted us permission to republish.

Y estábamos pasando el río cuando nos fusilaron con los máuseres. Me devolví porque él me dijo: ‘Sácame de aquí, paisano, no me dejes.’ —Juan Rulfo, El llano en llamas

US-Mexico border at Tijuana, Baja California (Tomas Castelazo)

On March 30 of this year, the National Border Patrol Council (NBPC) endorsed Donald Trump, effectively backing his bid for the presidency of the United States. NBPC president Brandon Judd heads the organization, which describes itself online as “the exclusive representative of approximately 18,000 Border Patrol Agents and support personnel assigned to the U.S. Border Patrol.” Judd himself published the NBPC’s pro-Trump communiqué, asserting that “if we do not secure our borders, American communities will continue to suffer at the hands of gangs, cartels and violent criminals preying on the innocent. The lives and security of the American people are at stake… There is no greater physical or economic threat to Americans today than our open border.”

In light of Judd’s predictable language, it is important to recall that the story of the Mexico–U.S. border dates far back in time and has quite a history unto itself. The NBPC president’s decision to invoke gangs, cartels and violent criminals, moreover, amounts to little more than a very lazy way of commandeering the polemics that currently inform border narratives. Judd’s language certainly reinforces the credibility of the racist whitewashing of border history that dominates the paradigms of millions of Americans today. For this reason, perhaps, it is paramount to acknowledge that —given the actual political and natural geography of today’s borderland— the U.S. military authorities, Border Patrol agents and local law enforcement are to blame for an unchecked and unquestioned campaign of terrorism, a racist agenda that continues to assail border communities and their peoples.

Policy and Profiling Along the Border

During the first two decades of the 21st century, the institutional practices of United States immigration officials have enhanced ethno-racial profiling along the Mexico–U.S. border. This deeper means of profiling is part and parcel of an age-old history of borderland colonization, which has long supported a reproducible kind of inequality that victimizes vulnerable border groups. As it stands, immigration policy espouses to (over time) enhance the furtive nature of America’s insidious immigration enforcement practices. It comes as no surprise that the state does virtually nothing to assuage the anti-immigrant climate that festers. So, immigrants of Mexican origin and “non-immigrant co-ethnics” must brave the hateful fog. The American state is only happy to be complicit; it would rather benefit from the growing racist sentiment, capitalizing on its nearly unchecked ability to deepen militarization and surveillance without unmanageable obstruction from public resistance and dissent. Such dystopian avarice for power (practiced through hegemony) certainly speaks to the deeper fissures that extend beyond racism and immigration; however, it still wreaks havoc on a great number of border lives each and every day.

The American people, whether expert social scientists or the uninitiated, have long witnessed how immigration laws militarize communities to incredible extents, thereby aggravating the institutionalized ethno-racial oppression that has served elites for centuries. In fact, each day the state harasses (or worse) workers and families all along the border. Such daily encounters can only be categorized as “ordinary violence,” as they occur with such frequency that they become normalized over time. The increasing militarization of the border itself is obvious: Run-ins with immigration officials and police readily serve as occasion to deploy military-level tactics and weaponry. A wealth of data documents the unjust nature of ethno-racial profiling, abuse and the institutionalized victimization of U.S. citizens and permanent residence of Mexican descent in the borderlands. Many people have testified as to the particulars of their experience with living in a bewilderingly militarized site. Many have testified about law enforcement practices, which commonly indicate that policy deliberately coincides with immigration-centric profiling and harassment. The fact that racially- and ethnically-charged profiling and mistreatment occurs in towns more so than in official ports of entry suggests predatory policy has had quite the spillover effect.

Borderland denizens endure physical, emotional, verbal and psychological violence, much of which stems from the overt mistreatment they suffer at the hands of immigration officials. Run-ins with such authority —whether within communities and towns or at ports of entry— adversely affect people who are simply performing routine tasks, such as work, travel, shopping and spending time with friends and family. The America that these residents inhabit is unlike the America that society’s privileged tend to enjoy. Because of this, researchers have asked the border peoples affected by state violence and institutionalized ethno-racial state-sponsored terror to document their perceptions of the everyday oppression that they routinely face. “Excessive” is but one albeit sanitized way to capture those feelings so that extra-border Americans may understand.

The type of violent subjugation that continues to oppress vulnerable groups along the border doubtless happens at the margins, and it is situated at a locus that researchers describe as the “capillary level”—that is, where interactions that occur in micro directly or indirectly reinforce violent norms. This is the selfsame violence that serves to galvanize the structural racism which U.S. immigration policy requires in order to sustain its oppressive success along the border. It is a manifestation of violence that is at once exploitative and oppressive, and arguably the American state has spent centuries perfecting it. Even if it manifests unknowingly, this violence stymies social growth and relationships by degrading even the physical health of its victims. What is more, this kind of ordinary, institutionalized violence is precisely where the ever-militarizing state exacts its power over marginalized groups that have long suffered under the thumb of the state and its elastic bouquet of violence and racism. It is important to recognize, though, that there is hope to identify exactly where the oppressive arm of the law continues to marginalize certain ethno-racial groups —be they U.S. citizens, permanent residents, or residents of Mexican origin or descent— along the border.

A View to the Past

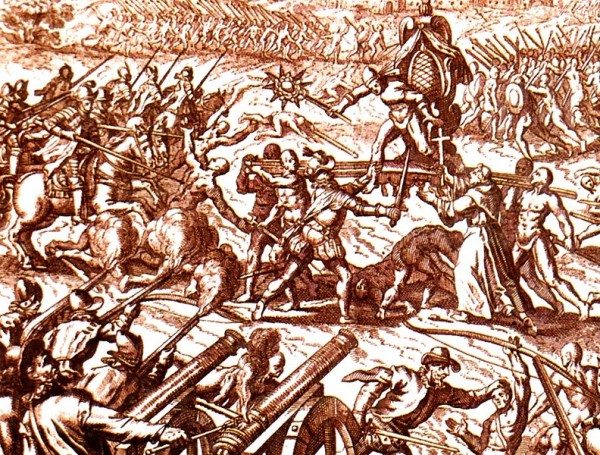

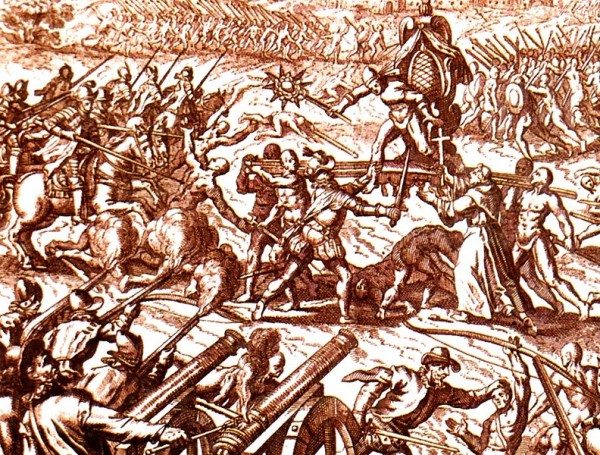

In order to establish a colonial system that would service their interests, the Spanish exploited and oppressed indigenous peoples throughout the Americas. After three centuries of such colonialism, social classes had become firmly institutionalized in Mexico. Class depended on race, birthplace and also the internalization of racial inferiority. The Spanish even devised different kinds of systems (i.e., hacienda and encomienda) so as to regiment social order, marginalize and subjugate indigenous peoples.

One salient point to be made about this time in history, especially given relevance to the state-sponsored racial profiling that occurs along the border today, is that the indigenous persons who appeared to have a more European physiognomy might enjoy some of the elitist benefits that Spanish colonialism had crafted in Mexico. On the other hand, however, those with a more indigenous mien could hardly hope to ascend socially. Instead, they were relegated to what colonial elites considered lesser social classes. Such racism belongs to a 500-year history in which people of Mexican origin, including those along the border, suffered at the hands of the Spanish, English, Portuguese, French, and Anglo-America and its government. Of course, all of these were foreign powers and had much in common.

A cursory peek back in time reveals that one of the most contentious issues in the foreign policy of Andrew Jackson involved Texas and the Mexican government. Pejoratively, historians have called the Mexico of this era the “sick man of North America,” partly because the nation’s government practiced the aging Spanish policy of inviting foreign settlers to move to Texas (so as to secure a buffer between itself and an aggressive United States). Two ideological tools the Mexican government employed to assimilate the American immigrants were the precepts of Catholicism and the ideals of antislavery. And upon invitation, Americans inundated the eastern portions of the territory that spanned San Antonio and the Sabine River. These American settlers relocated in Texas by the tens of thousands, and their outposts thrived. Whether or not they truly assimilated, most of the new colonists professed their allegiance to the Mexican government.

By and large the American settlers eschewed politics, though a group of dissidents and agitators became increasingly active at the outset of the 1830s. Some have described this group as demented, or filled “with schemes in their heads and guns in their hands—fleeing justice, fleecing Indians, gambling with lands , and promoting shooting scrapes called revolutions.” It was a motley crew that boasted slave smugglers like William Travis, and even the likes of a former Tennessee congressman and dear friend of Jackson, Sam Houston. Together, they called for the independence of Texas and its annexation by the U.S. government. They played a significant role in inciting the pending clash between Mexico City and Washington that would become the Mexican-American War.

In 1848, the signing of The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the war that the U.S. had declared on Mexico. Article X, a key element of the treaty, was neglected. Its purpose was to protect the rights of Mexican citizens dwelling in lands that Mexico ceded to the U.S. The treaty marked not only a loss of rights for Mexicans but also the loss of virtually half of Mexican territory (i.e., California, Nevada, parts of Utah, Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Oklahoma). Mexicans caught on the Yankee side of the border became a conquered group. Many were soon after displaced from their lands, and those who remained in the United States and gained citizenship after a year’s time were considered to be Mexican Americans. Whether Mexican or Mexican American, all faced immense discrimination and exploitation principally as a means of cheap labor. This was not entirely dissimilar to the indigenous groups of colonial Mexico. To ensure economic supremacy along racial and ethnic lines, Mexicans and Mexican Americans were not enfranchised with the same political and land rights as whites, or Anglos.

During subsequent times of economic downturn, the American state has scapegoated Mexicans and Mexican Americans. And during times of economic boom, the same people have been treated as cheap and expendable sources of labor. If people of Mexican origin could not present documentation of U.S. citizenship, they were subjected to deportation. Mexican Americans, on the other hand, were forced to study in segregated (or Mexican) schools, lived in segregated neighborhoods, and were viewed as “lesser than” the Anglos. America’s social science community launched a readied assault on Mexican Americans and their culture by propagating so-called “cultural deficit models.” These propagandized models categorized and assessed Mexicans to be “passive,” “irrational,” “unscientific,” “masochistic,” “apathetic,” “fatalistic,” “lazy,” “lacking initiative,” and liable to act in “criminal” ways. An attack on Mexican culture ensued and was decried the root cause of Mexican Americans’ so-called “social pathologies.” Anglo society largely prescribed assimilation by English-only education as the cure. They believed Mexicans and Mexican Americans were deficient in the cultural values necessary for economic success. The need to assimilate Mexicans and Mexican Americans into Anglo-American society was thus taken for granted.

Lynchings

A century ago, in 1916, a Wisconsin newspaper remarked: “That there are still lynchings in the far west, especially along the Mexican border, would hardly seem to be open to question, although they escape the average collector of statistics. The subject is one that invites searching inquiry.” For more than 80 years, from 1848 to 1928, systemic analysis failed to assess the lynching of Mexicans that took place in the United States. There was very little scholarly concern for Mexican lynchings during this time, and the resultant models that sought to explain the mob violence that Mexicans suffered did not really exceed the narrower, racial focus on blacks in the South. A conservative estimate finds that nearly 600 Mexican lynchings took place between 1848 and 1928 in the U.S. Historians put forth this number with a word of caution: the definition of lynching has changed so much over time that an accurate collection of mob violence data is practically impossible. Used here, the term “lynching” indicates an act of murder that is retributive and/or committed by a person or persons claiming to act on behalf of the interests of justice, tradition, and the community or common good. Even despite all efforts towards a working definition of lynching, a precise count of Mexican victims is generally considered impossible to render.

Mexican and Mexican Americans lived under the threat of lynching during the last half of the 19th century and during the first half of the 20th, and lynching was very much a part of the ordinary violence of the day. Some historians suggest that from 1882 to 1930 the likelihood of Mexicans becoming mob violence murder victims was comparable to that of murder victims who were African Americans. For African Americans living in Alabama during this time, the rate of the violence in question exceeded 32 persons for every 100,000; in South and North Carolina, the rate exceeded 18 and 11 persons (respectively) for every 100,000. For Mexicans during this time, the figure exceeded 27 persons per 100,000. And from 1848 to 1879, Mexican lynchings occurred at a rate of 473 for every 100,000 person population sample.

Compared to a rate of 53 for every 100,000 person population sample of African American victims from 1880 to 1930, a period considered by scholars to be the period most replete with mob violence in the “lynch-prone” South, the mob violence Mexican faced was still unparalleled. And just as historians argue that the act of lynching is vital to understanding the African American experience in U.S. history, they likewise note that the history of lynching is important for the Mexican and Mexican American experience. Lynchings took place most commonly in the four southwestern states: where Mexicans were most concentrated there and in the largest number. The history of Mexican lynching in the U.S. is rarely talked about and is certainly a significant chapter in the Western history of white (Anglo) expansion and conquest.

Blood Latitudes and Frontier Violence

Traditionally, the extra-legal violence of frontier vigilantism has been considered a product of the inability of government and legal institutions to keep pace with the rapid evolution of the frontier itself. Historians have maintained that, in lieu of the absence of legal entities and powers, frontier folks had no choice but to take control of matters and assume a role of legal authority: hence the validation of vigilantism as a legitimate means of settling the American West through violence, and hence the depiction of such vigilantism as a legitimate means of preserving a tenuous means of order and security throughout frontier communities. At times, this vigilantism has been credited with paving the way for a proper legal system. One historian even touts frontier vigilantism as a positive element of the American experience: “Many a new frontier community gained order and stability as the result of vigilantism that reconstructed the community pattern and values of the old settled areas, while dealing effectively with crime and disorder.” There is no doubt that conditions on the frontier allowed for the coming about of vigilantism; nevertheless, the conventional interpretation of western violence and vigilantism along the frontier cannot be successfully applied to the Mexican lynchings.

A major problem is that the civic virtue of vigilantes is taken for granted. The guilt of their victims is also considered to be implicit. Even so, the popular tribunals that condemned Mexicans to death were all but virtuous and seldom adhered to any “spirit of the law.” Whites (Anglos) refused to qualify courts of law when Mexicans either controlled or influenced them. And in order to restore the equilibrium of political (and racial) power, they established their own means of justice. For example, in 1880s Socorro, New Mexico, an Anglo “vigilance group” manifested itself, and mainly in opposition to Mexican legal authority. Nor did these groups show much respect for the legal rights of Mexicans when they executed them—and in numbers that were disproportionately large. Such vigilantism can hardly count for little more than makeshift institutionalized racism and discrimination, a kind of attitudinal cocktail that predates today’s border militarization and the ordinary violence that accompanies now it. Consider, moreover, the fact that little more than 10 percent of the nearly 600 Mexican lynching victims were killed by organized vigilante committees. The overwhelming majority of these victims were “summarily executed” by means of mob violence and the outright denial of a trial. Mexicans were sequestered from courtrooms and jail cells and then executed. So, in no way, shape, or form did these mobs act in the interest of upholding the law; instead, they acted out of a depraved desire to satisfy their penchant for racist prejudice against racial and ethnic minorities.

A Kind of Border

It is not merely an unforeseen irony that Mexicans and Mexican border entrants would be forced to assume the moniker of “terrorist” and suffer a contrived association with international terrorism in the 21st century. Border security, which the terrorist attacks on 11 September 2001 pushed to the fore, can be clearly but partly understood as a socially created concept whose political environment contours its significance. This extends to the Mexico–U.S. border, the American state and border history, beginning with Spanish imperialism. Taken together, reframing the border and its entrants as a cohort of people who pose myriad potential terror threats cannot, in any honest way, be situated in an objective sense of reality. Instead, border security is very much a contrived sort of specter, something endogenous to the socio-political construction of the border itself. Clearly, then, something as pressing as border security belongs to a deep-seated history of extra-legal violence, militarization, exploitation, and murder. This is the kind of border that has been carved into maps and inked with the blood of thousands of innocent victims.

Though the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo and the 1853 Gadsden Purchase combined to create what is now the U.S.-Mexico border, it was not until 1924 that the US increased its borderland military presence via the creation of the Border Patrol. Afterwards, in the 1930s, an economic slump would and anti-Mexican attitudes would combine to foment mass deportations of Mexican people. These deportations carried on even into the 1950s, thanks to “Operation Wetback.” Today, the safeguards afforded us by Homeland Security along the Mexico–U.S. border continue what is the now centuries-old propensity of the American state to wage physical and psychological violence against Mexican Americans, immigrants of Mexican origin and other non-immigrant co-ethnics. Such aims are visible through policy and terrorist tactics like “Operation Hold the Line,” or “Operation Safeguard.” Rampant civil rights violations of groups —Mexicans, Mexican Americans, Native Americans, etc.— have been plainly documented.

The American state has, through subjugation and repression, engendered a model of internalized colonialism in the Southwest. The characteristics of this model are fairly recognizable and harken back to a time when imperial Spain busied itself with colonizing the Americas on behalf of the economic elites in Iberia. The hallmarks of the model currently afoot are: the exploitation of people for the sake of cheap and/or expendable labor; the dispossessing of people of their land; the gerrymandering of voting districts and the treating of people as “conquered” in order to serve the economic and political interests of the greater American society. A century-and-a-half of Anglo America’s neocolonialism has led to the conquest, the occupation and the subsequent subjugation of two-thirds of what was Mexico. In turn, Mexican American landowners, workers and laborers and others throughout the southwest have experienced the ethnocentric discrimination and racist militarization of police forces and Department of Homeland Security surveillance reach its zenith in the 21st century. Effectively, the U.S. model of colonial internalization has become very much a successful, and ongoing, project.

Parasitic opportunists working in Washington have certainly made their contributions to the present mess of things. And while in the material world immigration and crossing the border is a very real thing, the nature of immigration and border security is steeped in the political processes that political elites, security alarmists and bureaucratic actors who have long sought to entrench themselves (to their personal benefit) in the wake of the Cold War. They took absolute advantage of the longstanding conflicts in national and ethnic identities and the attitudes that people have held toward migrants. They preyed on people’s perceptions of migrants in order to construct state policy that would elevate the security threat that border entrants posed to that posed by terrorist. No doubt these political actors, who were so deep within the American state, did all this just to stay behind the curtain, pulling the levers of America’s political machinery in the twilight of the Cold War.

Clinton Gets Serious About the Border

October of 2000 marked the eighth year of America’s attempt to enhance border enforcement The goal was basically to gain control of and minimize unauthorized immigration across the Mexico–U.S. border. Beginning in 1993, two shifts in policy made this experiment possible. To start, the young Clinton administration decided it was time to take border enforcement “seriously,” an attitude that manifested itself in a sustained increase in the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) budget—namely, the money allotted to enforcing the border. By 2003, the Clinton administration’s actions had made INS the largest federal law enforcement agency after the FBI. The second thing the Clinton administration did was to concentrate along a small number of short border segments the new resources it was making available to border control. These segments, or corridors, happened to be the most frequently used passages amongst would-be unauthorized migrants.

Also in 1993, the Clinton administration and its Office of National Drug Control Policy sponsored an investigation to find new kinds of methods that would up border security. The federal government specifically supported Sandia National Laboratories, which performs research in service of the military. Findings suggested that the Border Patrol would be best-suited by focusing on entry prevention. This meant determent rather than apprehension along the border, including within the U.S. interior. Researchers that examine this development in Clinton’s border policy consider it the point of inception for “prevention-through-deterrence,” which the INS assumed as its general operating procedure. And to ensure a difficult entry, Clinton would take the Sandia report’s advice on making entry more arduous by fixing numerous physical barriers and “advanced” electronic and surveillance technology.

During this time, Silvestre Reyes, a Democratic Congressman and the region’s Border Patrol supervisor, espoused a kind of border security enforcement plan for his area. He planned for Border Patrol agents to space themselves and their vehicles ever so far apart along the Río Grande. The plan was for them to perpetually intimidate potential entrants. The INS was not ecstatic about this plan but nonetheless supported it and realized dramatic outcomes in the short run: Apprehensions dropped by more than 75 percent during the 1994 fiscal year. Yet, one scholarly study concluded that this border initiative in El Paso accounted for the deterrence of mainly “commuter migrants” living in the adjoining Mexican city of Juárez who tended to commuted on foot every day to service jobs. These were not the long-distance entrants from deep within the Mexican interior that the INS and Border Patrol agents had envisioned preventing from moving past El Paso and its urban center.

Unsurprisingly, the U.S. government did not wait for any serious evaluation of this or INS statistics regarding apprehensions in following years. Instead, congresspersons, local authorities and the mass media extolled the success of the experiment in El Paso. The INS was then under formidable pressure to replicate the process in San Diego and other principal entrances into the U.S. In effect, the experiment in El Paso prompted a chain reaction that affected decisions in policy, the adoption of certain strategies (i.e., “concentrated border enforcement”), and so on. Some noteworthy details include: the addition of thousands more Border Patrol agents in specific areas; portable and stationary high-intensity stadium lighting; ten-foot-tall steel fencing fashioned out of Vietnam-surplus helicopter landing mats; stationary and mobile infrared night scopes; thermal imaging technology to physically map and locate entrants; remote video surveillance systems with links to ground sensors that trigger automatic video camera surveillance; new roads along the border; and a new biometric scanning computer system known as “IDENT,” which would photograph and capture fingerprints and biographical data and date and location of entrant apprehension.

Increased Border Enforcement and the Consequences

At the turn of the millennium, several authors had published on Mexico–U.S. border security policy. The sketches they rendered more or less agreed with each other. Accordingly, the American state gravitated towards specific local initiatives towards the end of the 1970s and 1980s in its efforts to stem narcotics and entrants from crossing the border. Also, the state was able to engender a much more sweeping and ambitious campaign that, during the early 1990s, would allow the country to boast that it had effectively sealed international border. The corresponding regulation cost billions. It materialized in boots on the ground, “high technology” and lukewarm security measures like fences. Policymakers leaned on the then-dominant mythos surrounding the power of technology and manpower and how such power warranted a faith in the U.S. government to be able to effectively secure its borders and firmly maintain them under control. It should escape none who read this that such developments invariably conjured tension between the neoliberal global economic strategy to de-border the world, and the intense geopolitical penchant for enacting and enforcing effective border security measures.

Though they successfully redirected the physical migration of border entrants, U.S. border enforcement tactics also significantly increased the physical risk, as well as the cost, which to this day coincides with “crossing” and entry. It is absurd to think that increased physical danger, as a result from concentrated border enforcement, are merely unintended consequences of policy and militarization decisions that the American state has opted for. In fact, such tactics as “prevention through deterrence” were always integral to the INS’ strategy on the border. To increase physical risk, the likelihood of apprehension, and the cost of crossing the border, the INS squarely expected to dissuade border entrants simply to go back home, a logic that would only sink in after the death toll rose.

Since the early 1990s, this strategy has affected a large amount of people on multiple levels. It has made for a lucrative business in terms of human trafficking, as prices that coyotes (people-smugglers) charge have skyrocketed relative to which corridor they are working and the services they pretend to offer migrants. Since the mid 1980s, coyote fees had been on the rise, and INS protocol and Border Patrol policy and practices only strengthened that trend. In terms of the Mexico–U.S. border market, human traffickers had yet to price themselves out at the turn of the millennium. And this is a service that —regardless of the economic strains that it placed on migrants who had to save and borrow in order to finance their lengthy and costly trip— predated the border enforcement policy INS and Border Patrol that began in the 1990s.

Yet another trend that predated 1990’s border enforcement policy was the rate of permanent settlement amongst “undocumented migrants” in the U.S. Again, the INS/Border Patrol strategy seems only to have accelerated that trend, too. During this period, which is one of much more stringent border enforcement, studies show through multivariate analysis that the combination of border enforcement and experiences with human trafficking lowered the probability for people to return to their country of origin. This was especially true of Mexican males. Besides these correlations, another serious consequence was the drastic increase in migrant deaths.

Mexican consulates on the Southwest border reported that from 1994-2001, roughly 1,700 people died while attempting to gain entry into the U.S. It was not until 1998, however, that the Border Patrol began to systematically assemble statistics on border-crossing deaths, which in some ways is gloomily reminiscent of the counting problem in Mexican lynchings from over a century prior to all this. Reports show that at least 1,000 migrants died from 1997-2001 alone. If one considers the increase in border enforcement intensification in Arizona, California and Texas from 1994-2000, one sees that the incidence in migrant deaths increase instep with the upping of border security in those same years. Again, as with the lynchings of the mid-18th to early-19th centuries, the available numbers grossly understate the quantity of actual deaths along the border; the underreporting of migrant bodies by the Border Patrol and also Mexican officials speak to the tragic reality that countless bodies lie unrecovered and strewn across miles and miles of mountain and desert along the border. Needless to say, this is in part the result of an increase in the militarization of the border, which evermore pushed migrants into remote and deadly areas.

The Border and Transnational Social Trauma

Much of the poetic language that surrounds the Arizona, California, New Mexico and Texas deserts seems to all but soften the pernicious policy that has consigned so many to a shameful death within those deserts. The language, curiously enough, speaks of the deserts claiming lives. Though the scientific truths about human lives perishing in extreme conditions are not in question here, it is imperative to recognize how they are used to paper over the fact that the violent war on migrants and border entrants is anything but an “unfortunate consequence” of a misguided decision to cross in the first place.

What is less tolerable is the attitude that some have apropos the fatal crossings, which they countenance as migrants’ “just deserts” for breaking the immigration laws of the American state. In both cases, the underlying (and highly erroneous) premise is that private, insular decisions, which exist in a virtual social vacuum, are alone responsible for informing the individual decision to cross. It is a premise that so infuriatingly ignores the intersectionality of the economic, the political, the social, the cultural—the endless forces that render impossible any tenable notion of a solitary choice on the part of the migrant or border entrant. Considering the standard of border militarization, the criminal state actions that force migrants into lethal geographies, the international history of borderland vigilantism and violence, and the phony self-promotion of the neoliberal state’s ability to solve these problems, it is impossible to blame the victims.

The militarization of the border indicates that, within the bounds of the social imagination at work in the U.S., folks believe enough security at the border will stem the “tide” of border entrants and migrants that cross every day. The militarization of the border speaks to an attitude that many in the U.S. live and breathe in the political sphere, and it is an attitude that favors an insulated, prosperous nation-state free of terrorist threats, no matter how imaginary. The fruits of such a secure state belong principally to those for whom it is their natural, “God-given” birthright. The solution, many of these folks imagine, requires reversing the flow of people who cross at the border, which in turn requires the militarization of the border via the deployment of armed forces, a wall and taller fences, more advanced technology and minimal military schemes. Never mind the fact that these tiny efforts would do virtually nothing to stop the other 40-to-50 percent of migrants who, during the first decade of the new millennium, say, joined the U.S. population in myriad other ways. The staying power of immigration discourse has largely been that it makes a powerful cultural appeal to an increased militarization of the border, which many (albeit illogically) conclude is the only feasible and immediate solution to the “problem.” But these hasty sort of higgledy-piggledy rationalizations are about as well thought out as the extra-legal violence of borderland vigilantism of a century ago.

Borderlands residents have felt the effects of political border strife in times recent and past. Officials have increased the general level of alert. They have intensified the physical scrutiny of the border area, and they have stymied commerce and trade, even dampening local economies at times. Now, the saturation of inescapable run-ins with immigration officials (including the local law enforcement who enact policy pertaining to immigration and border enforcement through military-like tactics and arms) is precisely what has oppressed the border, its people and its unfolding history with what can only be described as excessive force and undue militarization. Researchers have shown that borderland communities experience feelings of being “under siege.” Encounters with law enforcement may occur anywhere: public or private spaces; formal or informal checkpoints. Abuse and detention may be arbitrary, and identity inspection may be discretionary. Yet, there will always be the needlessly oppressed whose identity and citizenship will be targeted for racist reasons that belong to a racist history.

The target groups of border militarization and enforcement only grow suspicious and distrustful of both the authority and the institutions of the American state. And who can blame them? Coping strategies likely include silence and the minimization of victimization, while the social psychological detriments, among other injuries, include internalized trauma, manifest stress, anxiety, and devastating mental/physical health conditions. The fear of reprisal and criminalization is also a real outcome, and the state actively works to usurp conduits of resistance to human rights violations, which is, and has always been, detrimental to the health of borderlands denizens. Ultimately, in the minds of the general American public, border security remains fixed in the heart of immigration reform. What is not so widely accepted, however, is the fact that securitization and militarization has already made it impossible for folks to exist without the constant threat of police-state harassment, especially that made manifest by immigration and local law enforcement. Another problem is that U.S. immigration policy sanctions anti-democratic practices like ethno-racial profiling, harassment, discrimination and other kinds of structural racism and ordinary violence.

Indeed, out in the desert the enemy cries wolf while stalking its true prey with a badge and a gun.

***

Mateo Pimentel is a sixth-generation denizen of the Mexico-United States borderland. Mateo writes for political newsletters and alternative news sources. He also publishes in academic journals. Mateo has lived, worked and studied throughout Latin America for over a decade. He is a graduate student at Arizona State University and composes and records music in his free time. He tweets from @Mateo_Pimentel.

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.