Earlier this month my son asked, “Dad, can you break down the LA Riots for me?” Since then, I’ve had several conversations with him about what happened in 1992.

I was 19 years old and had recently started college. I grew up down the road in the Florence neighborhood in the city of Los Angeles in South LA, about two miles from the 1992 epicenter of Florence and Normandie. Being from the neighborhood, I had a level of comfort that allowed me to drive around and navigate a community that had all but exploded into complete defiance. I remember those days like they were yesterday. The men with guns, the expressions of anger and the acts of desperation and violence. I remember the smell of fire and not seeing a single cop for miles on end.

But what I witnessed was not rioting. What I saw that day was the end result of 21 years of a failed policy called the War on Drugs. A war that is a war on the poor, a war on communities of color and a war on immigrants.

It’s a war that rages on today.

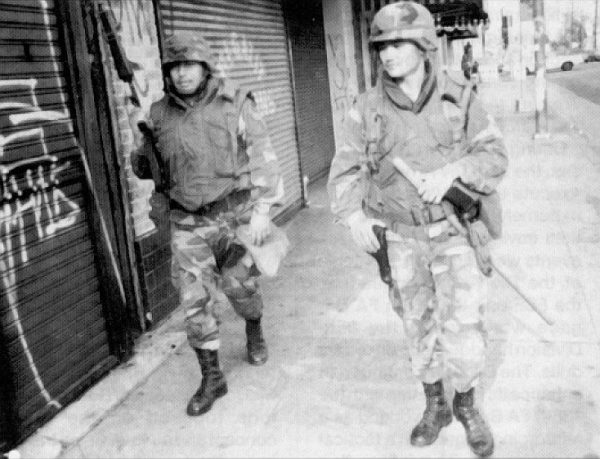

On April 29, 1992 at 3:15pm, a 12-person jury determined the police were not guilty and in doing so set in motion one of the largest acts of defiance to the government of the United States in modern-day history—an act that spanned from Hollywood to Long Beach and beyond. It is no wonder that by 10pm that night, then anti-immigrant governor Pete Wilson had already called upon the first 2,000 California Army National Guard soldiers, who amassed within six hours from being requested. All together by some estimates, government forces, in collaboration with state and local agencies —including close to 10,000 LAPD officers on the roster at the time— Los Angeles and neighboring communities were being patrolled by nearly 30,000 armed personnel within five days of the verdict. More than 60 people died and nearly 12,000 people were arrested.

When the verdict was read live on TV, I recall not being surprised. Months earlier, we saw the murder of Latasha Harlins, a teen girl shot in the back by a local merchant who only received probation for voluntary manslaughter. So it did not come as a surprise when these cops, who were also recorded on video beating Rodney King, were recused of any accountability, especially given the location of the trial in Simi Valley, home to the Ronald Reagan Library.

Ironically, it was Reagan who was perhaps the one person most responsible for the conditions that led to the events of 1992. It was 10 years earlier when the newly elected actor turned president declared in 1982 that “We must mobilize all our forces to stop the flow of drugs into this country.” A declaration made on the heels of an economic recession, Reagan would go on to win re-election two years later in 1984 and instead of stopping the flow of drugs into this country, we saw the rise of the CIA-backed Contra rebels of Nicaragua, a U.S.-funded right-wing militant group, who in collaboration with the CIA, started smuggling cocaine into our communities in 1985.

Los Angeles became a target.

It’s also important to note that at this period there was perhaps no other time in modern history when U.S. intervention in Latin America was greater, leading to a disastrous Latin American debt crises, civil war in some countries and massive amounts of migration, as entire generations of refugees sought refuge in the U.S. These communities started to settle in places like south Los Angeles—where there existed little to no community investment, no access to good employment or quality education. This neglect was accompanied by a cultural and societal shift, where African, Korean and Mexican Americans (among others) were forced to compete with each other, including refugee immigrants, for the little resources society had to offer. Unfortunately for those of us living in Los Angeles during the 80’s, the only resources the Reagan administration made available to us were resources that facilitated persecution, drugs, drug laws and mass incarceration.

The Reagan administration’s answer to the changing tides of the 80’s was to neglect these communities of color and instead enact and enhance the racist drug laws that achieved nothing more than mass criminalization and mass incarceration. There are several key pieces of legislation that created this outcome over a 10-year period. These included the 1984 Comprehensive Crime Control Act, which established longer sentences and increased the bail amounts for drug offenders; the 1986 Anti-Drug Abuse Act, which established the 100-1 crack versus powder cocaine disparity, leading to an unprecedented and disproportionate impact on black communities, although rates of drug use and selling have always been comparable across racial lines. By 1988, we saw the Anti-Drug Abuse Amendment Act, which increased sanctions for crimes related to drug trafficking while setting in place new federal offenses. Finally, the Crime Control Act of 1990 doubled the appropriations for drug law enforcement for states and localities, while strengthening forfeiture and seizure statutes.

What did a decade of draconian drug laws do to communities like Los Angeles? During this period in the U.S., the number of people behind bars for nonviolent drug law offenses increased from 50,000 in 1980 to over 400,000 by 1997, a more than 85% increase. In every year between 1980 and 2007, arrests for drug possession have constituted 64 percent or more of all drug arrests. According to Human Rights Watch, from 1999 through 2007, 80 percent or more of all drug arrests were for possession. By 1989 the total drug arrests nationwide had ballooned to more than one million, a trend that continues today.

According to the Public Policy Institute of California, African American men are dramatically more likely to be imprisoned than are other groups. Less than two-thirds of California’s adult male population is nonwhite or Latino (60%), but these groups make up three of every four men in prison: Latinos are 42%, African Americans are 29%, and other races are 6%. Among adult men in 2013, African Americans were incarcerated at a rate of 4,367 per 100,000, compared to 922 for Latinos, 488 for non-Latino whites and 34 for Asians.

The Reagan administration marked the start of a long period of skyrocketing rates of incarceration, largely thanks to his unprecedented expansion of the drug war an expansion that led to the unprecedented number of separated families, fatherless children and broken communities. Close to three million children are growing up in U.S. households in which one or more parents are incarcerated. Two-thirds of these parents are incarcerated for nonviolent offenses, including a substantial proportion who are incarcerated for drug law violations. One in nine black children has an incarcerated parent, compared to one in 28 Latino children and one in 57 white children.

When looking back at the conditions created by an entire decade of failed drug policies it’s no wonder why the community would respond the way we did in 1992. Looking back at the events of that week, it’s convenient (dismissive even) to describe the public disturbances acts as rioting.

In doing so, we fail to see the bigger picture of what it really was. What happened in 1992 was a community reacting to two decades of oppressive drug laws and unconstitutional policing. Years of frustration for a lack of civil liberties and right to self-determination underwrote the events of April 1992. What we saw that week was a rebellion by people who for the greater part of a decade were systematically profiled, targeted, persecuted, stopped, harassed, detained, arrested, convicted and incarcerated.

People were tired of having their families torn apart and their children raised by the streets and not their fathers. A people tired of being told, “this is your fault.”

What happened in 1992 was undoubtedly a complete and total act of rebellion and for some the only re-distribution of wealth they would ever have seen. Today, we find ourselves on the eve of a new wave of persecution under the newly elected anti-immigrant President Trump and his drug war attack dog Jeff Sessions, who recently vowed to increase drug crime enforcement in what some experts say is a return to the disastrous era of the 1980s that led to the 1992 Rebellion.

Will history repeat itself?

***

Armando Gudiño is a political strategist and analyst based in Los Angeles. He is currently a Policy Manager at the Drug Policy Alliance’s Los Angeles office, where he focuses on Latino outreach strategies, public policy and drug reform legislation focused on issues of mass incarceration, taxation and regulation of marijuana, and drug policy in the Latino community.