This story is a collaboration with Feet in 2 Worlds (Fi2W).

Arleene Correa Valencia was just four years old when she was brought across the border from Mexico by a coyote who used passports from American-born children to bring her and her siblings to the United States.

For the rest of her childhood in California’s Napa Valley, a renowned wine-producing region, she hid her immigration status. Now 23, Arleene uses art to spark conversations about immigration, although she remains fearful of of the consequences of being undocumented. She says she is “moving towards being an activist painter.” Arleene is currently completing her MFA at the California College of the Arts in Oakland.

This conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

How would you describe your art practice?

I need to tell people about my life. I need to reveal the truth to show what it’s really like and get rid of the misconceptions people have.

What are some of your current projects?

I’m working on oil paintings, large scale paintings of agricultural workers in the Napa Valley. I grew up there, so agriculture and agricultural workers are really important to me. I remember my uncle’s hands after he was picking grapes. I would see his hands full of cuts and bleeding, and his skin was dark and so tanned. Those kinds of colors are these beautiful earthy tones that I fell in love with. That’s what I’m working on now—depicting people as humans and not necessarily talking about them as undocumented or illegal aliens.

I can’t think of a single time I haven’t been scared for my life or for my parents or my family— no matter where I am. I’ve lived with people telling me I’m illegal, my existence is illegal, so I always feel like I’m doing something wrong.

What mediums are you using?

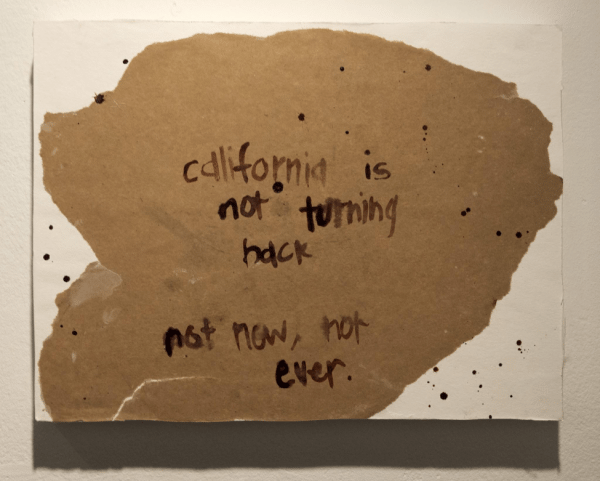

I’m using oil paint, I’ve moved away from painting with pigs blood. When I tried painting my feelings on the politics of immigration I felt that using oil paint was disrespectful to the history of paint for such a terrible person as Trump. I didn’t feel like he deserved to be painted with oil paint, something I love so much. The blood plays a very symbolic role in my culture—being Latino and always sharing the language, “you’re a pig,” “you’re disgusting,” that was just the one thing I could think of and I thought, ok, this is perfect. This is an appropriate medium that will suit the topic and will not disrespect my love for paint. But now that I’m talking about the immigrant, the human, I feel it’s more appropriate to use oil paint. It makes me really happy.

What response did you receive to the pig’s blood?

At first I got in trouble for using blood on campus and then I explained to them that it was clean, it was filtered. I presented my case, and they said ok, you can do it and then they kind of just rejected the work, they didn’t care for it. They shoved it into a corner, and my school pretended like it wasn’t even a thing. But then I got a residency in New York and it was well received. Everyone loved it.

Arleene painting at The Anderson Ranch in Colorado, 2017. (Photo by Ana Teresa Fernandez. Used with permission.)

What misconceptions do you want to challenge?

I think it’s showing people the efforts that we make to live as much of a normal life as an American citizen does, like filing taxes and showing that we also partake in these things. A lot of my friends have asked, “why don’t you try to get citizenship?” There’s a misconception that we don’t try, that there’s no effort on our part to try to become citizens.

Before I was married, I felt really scared because I felt I didn’t have an excuse or validation to become an American citizen, and after I married my husband I felt a little more faith.

Yesterday with my immigration lawyer, we had so many issues with my application and it’s not that we are not trying. There are a lot of requirements I’m supposed to meet. For example, I received DACA when I was 18½ years old. But I lived in California as an adult for six months undocumented and that, in itself, is breaking the law. That really hurts my application process. It’s basically impossible and that’s what I want to show and reveal. There is an effort, it’s just that the system doesn’t work in your favor.

How do you use art to show what life is like for people who are undocumented?

Recently I wrote a piece I call “Wetback Life Hacks,” a comical and also very serious how-to-live your life as an undocumented person. It reflects upon my childhood, going to school and all of my fears that I had. Like how to deal with not having health insurance, having a toothache, going to a bar with your friends and not being able to go in because you don’t have a valid ID, or like driving without a license. I guess all of my lessons reflect on these little moments of my life that I feel undocumented people go through and there’s just no way of knowing how to deal with them. Ideally, what my work will do is to show the real human and the real sadness of the lifestyle we are forced to live.

Do you believe in sanctuaries?

It’s a really tough question for me. I grew up in a two-bedroom apartment, living with 16 people, so sanctuaries are not really a thing for me. I don’t feel that I have ever had a safe place or a safe person. I’ve always been surrounded by fear, really. When I was six, the safest place I could find was the very bottom of the closet. I would hide for hours and I would take naps in there because it was the only place I felt no one could see me, no one could hear me. I was like non-existent and I didn’t feel fear. But that was when I was a kid, and other than that I can’t think of a single time I haven’t been scared for my life or for my parents or my family—no matter where I am. I’ve lived with people telling me I’m illegal, my existence is illegal, so I always feel like I’m doing something wrong.

El Mangonero/The Mango Man, 2017, 26 x 32 inches, Conté crayons. (Photo by Jen Velazquez. Used with permission.)

Do you think you can find a sanctuary in the art world?

I feel like art is my sanctuary while I’m making it. Once it’s revealed to the public or the viewer, I feel like it’s taken away from me because now I have to share it. It’s a public thing that I announce to the world and it no longer feels safe. For my entire life I’ve been told, don’t tell people about your identity, don’t tell people you’re undocumented. So, for me to make art and to be extremely open about it and be vulnerable causes me to feel like art is not my sanctuary because I’m doing the exact opposite of what I’ve been told to do my entire life.

Do you feel you’re creating sanctuaries for other people? Has anyone come up to you thanking you for your work?

Oh absolutely! It happens all the time. Recently, on my Instagram page I posted my permit-ID that they give you. I was like, “here’s the thousands of thousands of dollars thrown at the government to validate my existence with a piece of plastic.” I had messages from people that were like, oh my gosh I’m in the same place and I didn’t know that there was somebody who felt the same way, thank you for being so open about it. I think that’s what drives me and motivates me— the idea of being able to share something so private with other people and knowing that they feel validated as well.

How would you like to see the art world respond to the current political conversation regarding immigration?

I really just want people to speak out and talk about it and to not ignore it, and not pretend like it’s not happening because it affects so many people. For me it’s unrealistic that as a community, as an art community, we ignore the topic and we keep talking about the regular white male painter. I think as a society we are so past that and art is so powerful. If we use it as a tool to talk about such important topics right now then we can make a difference.

If you could create a sanctuary, what would it be?

The perfect sanctuary for me would be a place where undocumented children wouldn’t have to suffer the things I went through as a child. I lived in a huge house where there was a lot of domestic violence. There was a lot of drinking, really terrible things that are really hard for me to talk about. So if I could eliminate those from a child’s life by creating a sanctuary or a place of comfort with art activities, if there’s an after school program for children who don’t have to go home or have a place to go, that would be my ideal place.

For more of Arleene’s artwork visit her website www.correavalencia.com.

***

Feet in 2 Worlds (Fi2W) is an award-winning independent media outlet and training program that works with immigrant journalists from communities across the U.S., magnifying their voices and enhancing their skills. We produce radio stories, podcasts and online journalism—including videos, multimedia and text stories. Special thanks to New American Media.

Mai Nolasco is a filmmaker and founder of the blog Sonic Feminista—a platform that challenges the idea of who a feminista is supposed to be by producing videos that allow them to define themselves. She tweets from @SonicFeminista.