By Joel Cintrón Arbasetti and Carla Minet

SAN JUAN, PUERTO RICO — The same day Hurricane María struck Puerto Rico, Oppenheimer Funds questioned that the island’s government could not pay its $74.8 billion debt because in June it collected more taxes than estimated. A few days earlier, after Hurricanes Irma and Harvey, the company had said the municipal bond market could become a source of capital for affected municipalities that, “have to (or choose to) retrofit or replace critical infrastructure, or embark on a master plan to rebuild areas that were largely destroyed.”

Against all forecasts on the economic and fiscal situation of the island before Hurricane María, Oppenheimer painted an optimistic narrative. In December 2016, it assured clients that their investments in bonds issued by the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico had helped them maintain the performance appeal of their funds compared to their competitors. “The Puerto Rico credit picture continues to evolve and, in our opinion, improve,” they said. Eighteen months earlier, former governor Alejandro García Padilla had publicly expressed that Puerto Rico’s debt of was unpayable. Despite that, Oppenheimer did not mention this in its report.

In contrast, the Franklin Templeton Mutual Fund assured its clients a few months ago that in 2012 it had begun reducing exposure to Puerto Rico-related bonds due to the financial scenario on the island. According to a 2017 report, they retained those investments they believed were in the strongest position and had legal and constitutional protections. However, in the General Obligation bond issue the government of Puerto Rico made in 2014, and which major credit houses rated as “high risk” or “junk,” Franklin requested to buy $200 million, resulting in a $60 million purchase.

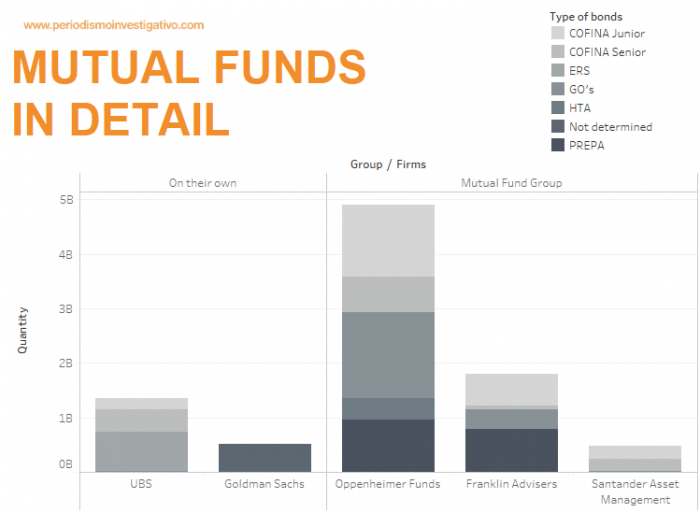

Those two U.S. companies allied themselves with the local mutual funds owned by Santander Asset Management, known as the First Puerto Rico Family of Funds, to form the Mutual Fund Group, creditors who claim the largest amount of debt in the Puerto Rico government’s bankruptcy under Title III of the PROMESA federal law. The group calls for the payment of $7.2 billion in General Obligation bonds, Sales Tax Interest Fund Corporation (Cofina), Electric Power Authority and Highways and Transportation Authority (ACT). The mutual funds Goldman Sachs Asset Management and UBS also claim Title III debts, but are not part of the group.

Mutual funds are companies that manage and invest for their customers in different products (e.g., bonds, stocks or real estate) to generate profits for them and their clients. For years, they have been a favorite investment vehicle for “mom and pop investors,” seniors, and retirees with moderate capital who expect to earn long-term profits. Oppenheimer Fund says it has spent more than 20 years investing in Puerto Rico; Franklin, more than 30. Both point out that the appeal of the island’s bonds is the fact that they pay no federal, state or local taxes in the United States (the so-called Triple Tax Exemption.) Another incentive mentioned is that within the debt issued by the government, the Constitution gave priority to the payment of the General Obligation bonds, while a portion of the Sales and Use Tax (IVU) is used for the payment of Cofina (Sales Tax Financing Corp.) bonds.

That’s how these companies sold the island’s bonds to low-profile investors who reside in Maryland, Ohio, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Colorado and Arizona. Those seemingly guaranteed investments ended up in the biggest bankruptcy in the history of a U.S. jurisdiction.

Mutual Funds Under Scrutiny

“The people who invested in mutual funds, generally, are not terribly sophisticated. They don’t sit down and figure out what is this fund. They might examine what’s the rate of return, what’s the general description—if it is a conservative fund, is it a risk fund, they might look at things like that possibly, but they don’t get into the detail of what that consists of. So therefore they are relying upon the people who put the funds together to protect them. Those people who put the funds together, they are regulated by my office if they do business in Massachusetts,” said William Francis Galvin, Secretary of State of Massachusetts, in an interview with the Center for Investigative Journalism.

In 2013, Galvin accused 15 brokerage firms, including Morgan Stanley (MS), Merrill Lynch (MER), UBS AG (UBS) and Bank of America Corp. (BAC), as part of an investigation into the way they sold “esoteric high-risk products” to elderly people.

“They are usually small-dollar investors. They’re not multimillionaires usually. They are people who are looking for safety. Mutual funds tend to attract investors who have less financial worth, and are looking for safety as opposed to people who have a lot of money and take risks. So they tend to be more conservative investors. Generally speaking, they don’t have a personal financial advisor, they don’t have a strategy on how to save money or make some money on their investments, they are not people with a lot of money, so that’s what makes them all the more vulnerable to this situation and that’s why we were concerned,” Galvin said.

In early 2017, Galvin opened a new investigation into the practice of selling Puerto Rico bond funds to determine if investors had been informed of the product risks. As part of the investigation, he sent letters to Oppenheimer Funds, UBS Financial Services and Fidelity Investments, a U.S. pension fund.

“There was a good reason in the beginning for mutual funds to see the Puerto Rican bonds as a good investment because of the [tax-exempt] status. But as the problems emerged, and Congress really hasn’t dealt with the problem at all, they don’t seem to be providing the money that’s necessary to deal with it or to come up with a comprehensive solution, the risk of a default to these investors is pretty serious,” he said.

“That’s why we were concerned: to see what exactly these firms knew and make sure they were aware of our interest in supervising what the decision-making process was. We were looking at those two firms [Oppenheimer and UBS] because they have a large presence in Massachusetts, but it was not limited to them. Our interest is a general interest. It’s not specific to either of these two firms. The inquiry began some months ago, maybe even late last year, I’m not quite sure, but it’s been a while,” the Democrat public official said.

Puerto Rico’s Biggest Creditors Duo

Oppenheimer tops the lists of Mutual Fund Group’s firms, and among all those claiming Title III debts, with $4.9 billion. Of that total, $1.5 billion is General Obligation debt, $1.9 from Cofina bonds, almost $394 million in ACT bonds and $957 millions in bonds from the Electric Power Authority.

This mutual funds firm, along with Franklin, sued the government of Puerto Rico in 2014 and got the U.S. District Court in San Juan and the First Circuit Court in Boston to declare the “Local Bankruptcy Law” unconstitutional. Oppenheimer further lobbied Congress to stop any attempt to give Puerto Rico access to Chapter 9 of the U.S. Bankruptcy law.

Oppenheimer is a subsidiary of Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company (MassMutual) one of the largest insurance companies in the United States. As of December 2016, it handled approximately $191 billion in assets under management.

Oppenheimer has paid more than $64 million in fines to federal financial regulators, the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA) and the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) for fraud and regulatory violations, from 2012 through 2016.

The firm’s CEO and President, Arthur Phillip Steinmetz, is a donor to the Libertarian Party in the United States, which enacts essentially Republican positions on minimal financial and regulatory intervention by the state, while promoting a progressive civil rights agenda. He also contributed to Republicans Mitt Romney and Mitch McConnell, and Democratic senator Charles Schumer. Oppenheimer Funds established a Political Action Committee (PAC) for the last election cycle that raised $356,841, distributing 40% to Democrats and 60% to Republicans.

In its 2016 report, Oppenheimer added that one of the positive factors for Puerto Rico was the election of Ricardo Rosselló as governor. The report stated: “An ardent supporter of statehood for Puerto Rico, Governor-elect Rosselló campaigned, in part, on a platform that included his resolve to work with owners of Puerto Rico’s municipal bonds to ultimately pay 100% of interest due on Puerto Rico’s outstanding municipal debt. While the success of any such effort remains to be seen, we believe that Governor-elect Rosselló stands to negotiate with bondholders in good faith, as he appears to understand the direct relationship that payment of existing debt bears to future access to municipal bond market borrowing. In total, we believe that Governor-elect Rosselló represents a positive factor for the future of Puerto Rico’s municipal bonds.”

A month later, after the Rosselló administration’s swearing-in, the executive director of the Puerto Rico Fiscal Agency and Financial Advisory Authority (“AAFAF” by its Spanish acronym), Gerardo Portela, sat down with Oppenheimer, Franklin and Goldman Sachs, the bond insurance companies, and several hedge funds.

Oppenheimer executives also expressed “hope” about the PROMESA law and the appointment of a Fiscal Control Board, which they characterized as “powerful.”

Perhaps now the firm sees it differently, as both the Rosselló administration and the Fiscal Control Board have earmarked less money to pay the debt than what the previous administration put on the table during negotiations. “The Certified Fiscal Plan (by the Fiscal Control Board) would require haircuts of between 62% and 79%, if implemented on a proportional basis. By comparison, García Padilla’s latest offer, which was rejected by the creditors, called for a weighted average haircut of only 32% across all credits,” says a June 2017 presentation by Millstein & Co., the García Padilla administration’s former restructuring advisors.

In January 2017, the firm made other comments to its bondholders, stating the following: “In a year when the phrase ‘fake news’ entered our national vocabulary, we believe that the media’s coverage of developments in and related to the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico could best be described as ‘partial news’.” It then explains why everything is going well with its investments in the island, although in the end it warns that the deterioration of Puerto Rico’s economy could have an adverse impact on Puerto Rico’s bonds and the performance of Oppenheimer Rochester municipal funds.

Five months later, in May 2017, when Title III had been certified as the process to renegotiate the debt, Oppenheimer maintained its optimism and told its clients: “While the situation in Puerto Rico remains challenging, the market for bonds issued by the Commonwealth remains liquid and Puerto Rico’s revenues stand at an all-time high.”

A month ago, the picture changed. Hurricane María swept away the sources of debt repayment. The central government that issued the General Obligation bonds now directs its resources to address the humanitarian crisis left by the storm. The Sales and Use Tax, part of which pays for Cofina’s bonds, has been waived on prepared foods since October 8. For a month, the highway tolls, whose revenues are used in part to pay off the ACT debt, were not charged. Also, part of the infrastructure of PREPA, of which Oppenheimer and Franklin are also creditors, was totally destroyed.

For its part, Franklin Mutual Advisers LLC is the umbrella company that has 22 different funds distributed in General Obligation bonds, Cofina and PREPA bonds. In total, they have $1.8 billion in debt and rank second among all creditors participating in Title III. Franklin Mutual Advisers LLC is a subsidiary of Franklin Resources, which in conjunction with its subsidiaries is known as Franklin Templeton Investments, with $65 billion in assets under management.

By having Cofina bonds and General Obligation bonds at the same time, Mutual Fund Group firms have a conflict. In the event of a Puerto Rico government bankruptcy under Title III of PROMESA, some General Obligation bondholders hold that Cofina is illegal because it was created to issue debt above the constitutional limit, using as a source of repayment a portion of the Tax Sale and Use (IVU). While the Cofina bondholders maintain that this part of the IVU belongs to them by law, those with General Obligation bonds are protected in that the Constitution establishes payment priority for such bonds.

Franklin Mutual Advisers is also part of the Ad Hoc Group’s General Obligation Bonds, where it claims $294 million in that type of bond.

In addition to coinciding as the mutual funds with more bonds in Puerto Rico, and its successful opposition to the local bankruptcy law, Oppenheimer and Franklin have teamed up for another task: political investment. Both firms participate in the Investment Co Institute PAC, which raised $1.2 million for the last U.S. elections and distributes its donations among Democratic candidates (34%) and Republicans (66%). Franklin’s top managers, Gregory E. Johnson and Rupert H. Johnson, Jr., have also been regular donors to key Republican figures.

Santander in the Mutual Fund Group

The Mutual Fund Group also includes Santander Asset Management —which along with its First Puerto Rico Family of Funds— has requested the payment of $478 million in General Obligation bonds, Cofina and HTA bonds. Santander Asset Management is a subsidiary of SAM Investment Holdings Limited, which in February 2017 was handling $1.6 billion in assets. Frank Serra Cardona, president and CEO of Santander Asset Management, did not answer calls from the Center for Investigative Journalism.

Dennis Williams, SAM’s Chief Investment Officer, said in 2016 that the Fiscal Control Board’s operation, despite being “politically controversial,” could bring economic stability, financial transparency and fiscal discipline to the Puerto Rico budget process. “We note that Puerto Rico municipal bond prices have improved during the two months following the adoption of PROMESA,” he said.

In the same report, it acknowledges that the First Puerto Rico Family of Funds could be affected by the Board’s decisions. “Depending on the approach taken by the Federal Oversight Board, its decisions may result in favorable or unfavorable actions to creditors. The Federal Oversight Board may elect to honor bondholder commitments, or it may decide to prioritize pensions at the expense of bondholders. The outcome for Puerto Rico bondholders will ultimately depend on the fiscal approach favored by the members of the Federal Oversight Board.”

The First Puerto Rico Family of Funds is a group of funds that belong to Santander Asset Management.

The firm offers mutual fund shares only to individuals and businesses residing in Puerto Rico. Those funds are mostly acquired by people for long-term investments, such as the payment of their children’s college tuition or retirement income. The firm is obliged by law to invest two-thirds of its assets in Puerto Rico securities, and have invested significant amounts of money in the government and its public corporations.

Between 2001 and 2008, Fiscal Control Board member José Ramón González, chaired the Board of Directors of Santander Securities and its subsidiary Santander Asset Management, the company that manages the assets of the First Puerto Rico Family of Funds. According to his partial financial reports filed as Board member, José Ramón González’s wife liquidated her investments in the First Puerto Rico Tax Exempt Target Maturity Fund II and IV and the First Puerto Rico Tax Advantaged Target Maturity Fund 1, between September and October 2016, shortly after González was appointed to the Board. The value of the withdrawn investments is not precise, ranging from $1,001 to $15,000 each, according to the financial disclosure report. The reported gain per fund fluctuates from $201 to $1,000. None of the items mention whether there was any gain or loss in the liquidation of these investments.

In August 2016, Carlos García, another Fiscal Control Board member who also worked at Santander, liquidated his investments in five First Puerto Rico Family of Funds vehicles: First Puerto Rico Target Maturity Income Opportunities Fund II, First Puerto Rico Tax Advantaged Target Maturity Fund I, First Puerto Tax Exempt Target Maturity Fund III y IV and First Puerto Rico Tax Exempt Target Maturity Fund II. García’s financial report is equally imprecise and states the value of each fund was between $1,001 and $15,000 and the amount of gains per fund was between $201 and $1,000.

González’s and García’s financial reports that have been made public are incomplete but have been certified by the ethics officer hired by the Fiscal Control Board, Andrea Bonime Blanc, who is supposed to evaluate whether the financial interests disclosed represent or do not represent a possible conflict of interest that affects that entity’s integrity. In addition, the documents disclosed cover a period after being appointed to the Board, and not before or during their evaluation process to that position. In June 2017, the Center for Investigative Journalism filed a lawsuit against the Board in which it requested these documents, in full form and as they were delivered to the federal agencies that evaluated them.

Santander informed that it will donate $2 million to local aid and relief organizations, non-profit organizations and a fund to help Bank employees.

The Toro, Colón, Mullet, Rivera & Sifre law firm, which represents the Mutual Fund Group in Puerto Rico, did not respond the Center for Investigative Journalism’s attempts for questions about its client.

UBS Requires Payment for Fraudulent Bonds

The UBS Family of Funds are “closed mutual funds” managed by UBS. They are the third largest creditor of the government with $1.4 billion distributed in 89 funds with Cofina bonds, the Highway and Transportation Authority and the Retirement System.

The Center for Investigative Journalism found that all of the individual funds over which UBS is suing the government have been fined and reprimanded by the SEC for false representation and omission of data to its customers regarding the price of the bonds.

“Our shareholders consist primarily of individual retirees (and near retirees) that reside in Puerto Rico. These shareholders have invested their savings through the Puerto Rico Funds, and many of them depend on COFINA’s principal and interest payments to survive,” UBS’s motion in the Title III case stated.

In 2015, in one of the cases against UBS involving these funds, the SEC accused stockbroker José Ramírez, Jr. of fraudulently selling, through misrepresentation and omission of information to clients—approximately $50 million of the mutual funds. The SEC indicated that UBS lacked mechanisms to supervise the broker. However, an audio leak from a UBS executive board meeting point that the claims and fines the firm paid suggest fraudulent bond sales as an institutionalized practice within UBS.

Goldman Sachs Doesn’t Reveal Its Numbers

Meanwhile, Goldman Sachs Asset Management (GSAM), which has General Obligation and Cofina bonds, is a division of Goldman Sachs, one of the world’s largest investment banks that the U.S. government bailed out by during the 2008 financial crisis, with $10 billion in federal funds. In 2010, the SEC indicted Goldman Sachs for fraud during the U.S. subprime mortgage crisis and in January 2016 the U.S. Department of Justice ordered it to pay a $5.6 billion fine.

In its most recent June 2017 report, the head of the Municipal Bond Portfolio Management division at Goldman Sachs, Ben Barber, anticipated that the Title III proceedings would be handled through a mediation process and ensured: “If the Court is obligated to certify a plan that both parties have not agreed on, we will probably enter into a long process that could last several years.”

Goldman Sachs has other interests in Puerto Rico. For example, its Goldman Sachs Infrastructure Partners II LP division, along with Abertis Infrastructures, won the bid for the privatization of the PR-22 and PR-5 highways that former governor Luis Fortuño’s administration carried out in 2011, earning them a contract of more than $1.4 billion for 40 years.

Also, Goldman Sachs Realty Management, a limited liability company incorporated in Delaware, completed a certification of authorization to do business in Puerto Rico on January 11, 2017.

***

Laura Moscoso collaborated on this story.

The “The Creditors That Control Puerto Rico’s Bankruptcy” series of the Center for Investigative Journalism digs into in the characteristics and the background of the investment firms that until now have dominated the government of Puerto Rico’s bankruptcy case. A new round of stories will be publish this week and next week.

This reporting was supported by a grant from the Leonard C. Goodman Institute for Investigative Reporting.