On a night in which the clouds escaped onto Riverside Park with the accompanying setting sun, I met some friends, all of whom were of color, outside of Butler Library, the notoriously imposing library on Columbia’s Morningside Heights campus. My friend Kalsoum, who’s from Senegal, goes on to talk about her disdain for ancestry tests.

“I am fully Senegalese,” she exclaims, with pride and colonial resentment, “and I will not believe an ancestry test if it says otherwise.”

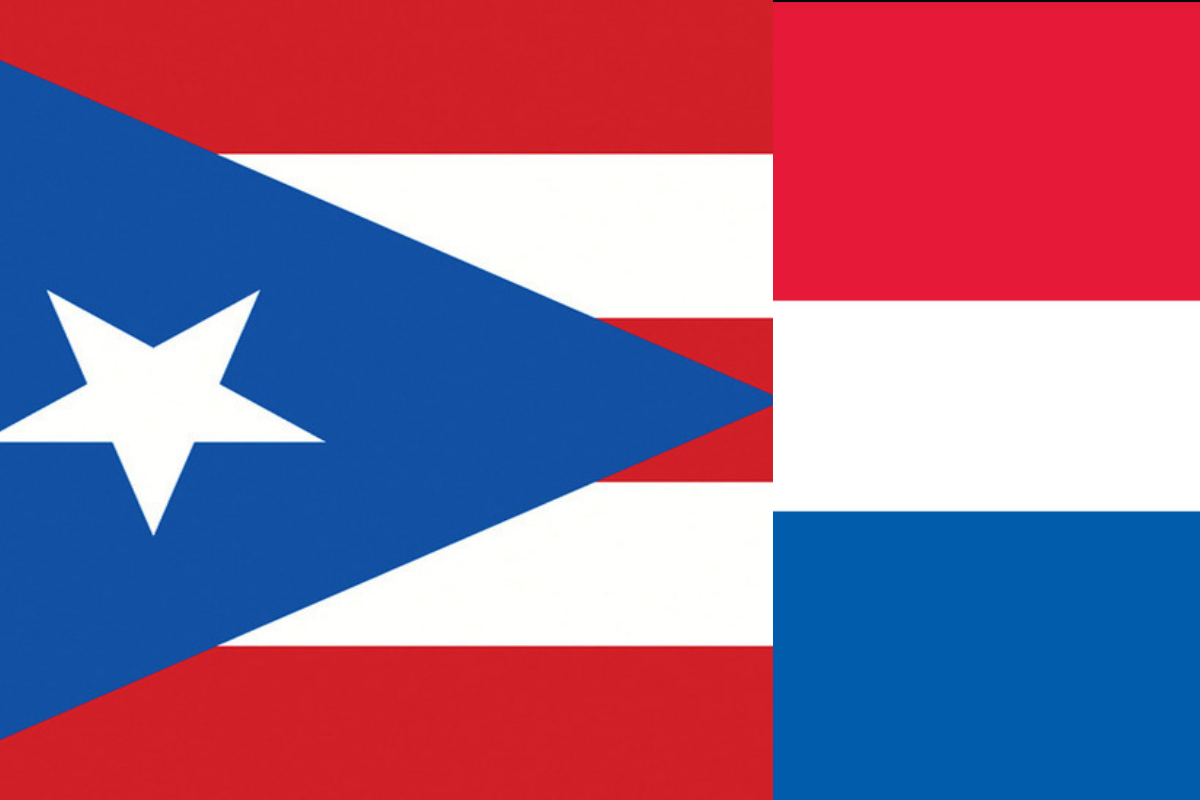

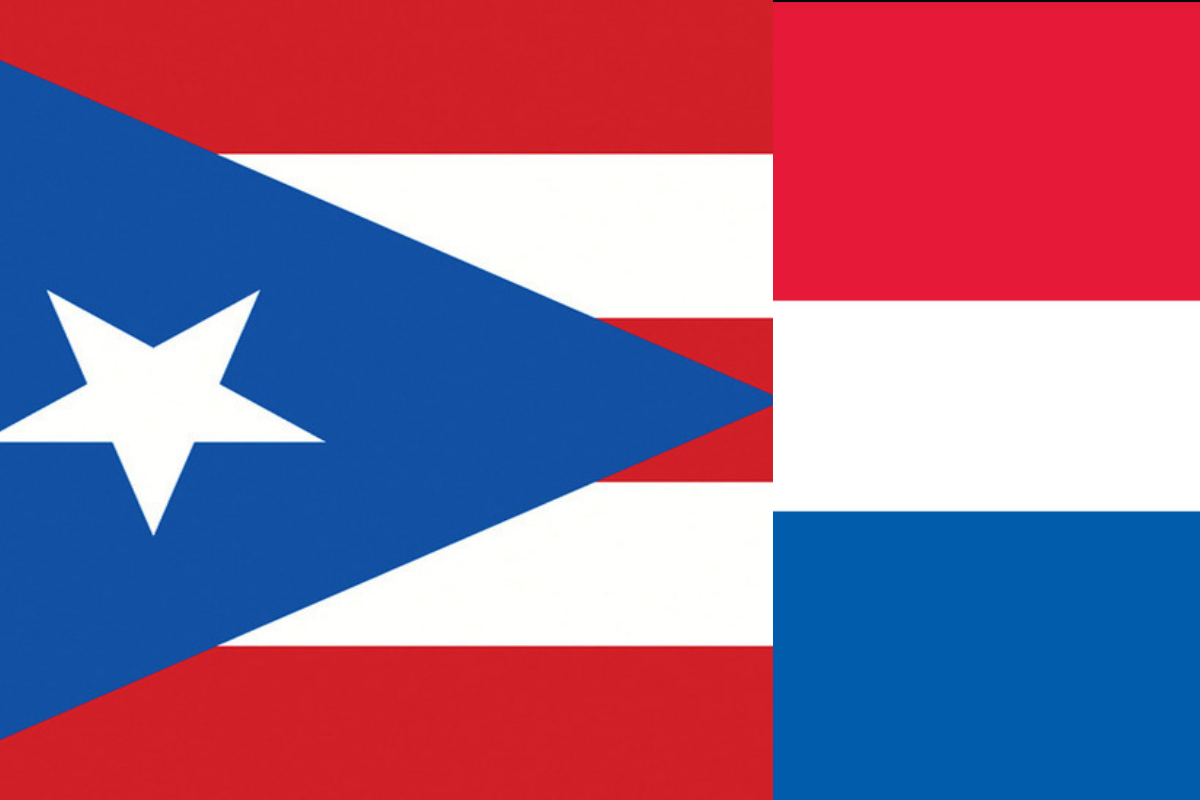

My friend Nelson goes on to say, “I am 75% Puerto Rican, 25% Dominican.”

But how accurate is his assertion?

Exclaiming “I am 75% Puerto Rican, 25% Dominican” is like saying “I am 75% American, 25% Canadian,” a preposterous notion when speaking of these North American countries, but an accepted notion when speaking of Latin America. Statements of this kind reveal nothing more about a person than the national origin of their parents and limit these nations to singular ethnic groups, which is far from reality.

Therefore, the question “Where are you from?” can be quite confusing for children of immigrants. The predicate “to be” and the preposition “from” can mean so much denotatively—and connotatively, I struggle to realize whether the interrogator wants to know where my home is or where my family comes from.

My answer: “I am Dominican.”

But this statement is as accurate as Nelson’s. I grew up with perico ripiao and bachata classics strumming through my apartment’s walls. I was used to having the biggest meal of the day for breakfast: mangú con los tres golpes. And nothing screams “Dominican!” more than the Cibaen twang that hugs my Spanish accent. Yet on paper, I am only American. I don’t have a Dominican passport nor Dominican citizenship.

So what does it mean when I say “I am Dominican?” It means it is the first identity I knew, and the one I continue to know best. When I say “I am Dominican,” however, people assume that my parent’s nationality reveals my racial background. In reality, my Dominicanness is independent from my race.

According to a Pew Research Center poll, 69% of young Latino adults ages 18 to 29 believe that their Latino background relates to their racial background. This assertion is misinformed: being Latinx simply means that one has origins in a nation in the Americas where a Romance language is predominantly spoken. (Yes, this includes Brazil, and even Haiti!)

People from Latin American countries can be of any race imaginable. There are nearly 400,000 ethnic Chinese people in Venezuela, over 6 million indigenous people in Bolivia, over 13 million Black people in Brazil and over 38 million white people in Argentina.

Therefore, saying “I am 75% Puerto Rican, 25% Dominican” perpetuates the narrative that Latin American countries are racially uniform and that one can somehow be a “percentage of a nationality.” Latin America is akin to the United States in that it is comprised of countries of forced or voluntary immigration, with the exception of the indigenous populations.

When I say “I am Dominican,” I am referring to the culture I belong to: it has no bearing on the texture of my hair or the color of my skin. Chinese Dominicans, Arab Dominicans, and Jewish Dominicans are just as Dominican as the mixed population that has predominated the country for centuries. Let’s remind ourselves that Latin America is not racially monolithic, especially when the history of people of color in Latin America has been that of marginalization and mobilization. Erasing indigenous, Black, and Asian roots is erasing that history.

So when someone asks me “Where are you from?,” I will respond with “Brooklyn.” And if that answer leaves them unsatisfied, I will entertain their confusion and say “but my parents are Dominican.”

Because even though I am culturally Dominican, “Dominican” is not a race or ethnicity, but a nationality, and there is no such thing as being “25%” of a nationality.

***

Diogene Artiles is a Brooklynite at Columbia University studying English and Latin American Studies.