Presidential-elect Nayib Bukele on the campaign trail in San Salvador, El Salvador, on January 13, 2019. (Photo by Marvin Recinos/AFP/Getty Images)

Nayib Bukele made history in El Salvador when he won the presidential elections February 3, ending decades of two-party rule. Hailed as a young, millennial, anti-corruption candidate, Bukele won by over 20 points ahead of the right-wing Nationalist Republican Alliance (ARENA) candidate, Carlos Callejas. While Bukele’s win is a sign of change for many, his stance on same-sex marriage and LGBTQ rights, in general, is concerning for local advocates.

In October of 2018, the presidential electoral campaigns in El Salvador were in full swing and María Luz Nóchez, a journalist working for the award-winning outlet El Faro, was out covering one of the candidates: the 37-year old Bukele. That day, he and his running mate, Félix Ulloa, had gone to a Jesuit-led university in the country’s capital to address the student population about their campaign platform.

The place —inside and out— was packed, and the audience clapped effusively each time Bukele talked about cracking down on corruption. But during the Q & A that followed, someone from the audience prompted Bukele to express his thoughts on same-sex marriage. The social media savvy candidate said he had gay friends and acquaintances, but that said marriage could only happen between a man and a woman. “Water is in a bottle and I have the option of drinking it there or in a cup, but that does not mean the cup is going to become a bottle,” El Faro reported him saying.

“There was this big silence when he said that,” Nóchez said in Spanish during an interview with Latino USA. “People did not expect that response.” According to Nóchez, this was the first time the candidate publicly took a stance on a topic linked to the LGBTQ community and that —in conservative and religious El Salvador—could potentially become a polarizing issue and translate into voters defecting for other candidates.

A few weeks before that statement, Bukele had taken the country by storm when he announced, via Facebook Live, that he was running for president. Now he will become El Salvador’s youngest president. But whereas in other Central American countries —such as Costa Rica— same-sex marriage became a galvanizing issue on which the election hinged, in El Salvador it was more like the non-issue candidates tiptoed around, and Bukele had so far been mute on the topic of LGBT rights.

“If you want popularity, talk about fighting corruption,” said Nóchez. “Not this.”

Although human rights organizations point to the lack of official data on hate crimes committed against LGBTQ people in El Salvador, violence against the marginalized group is a grim reality, where same-sex marriage is illegal, and discrimination an imminent threat for transgender people, since the law forbids changing public documents to reflect the gender a trans person identifies with.

“Trans women in El Salvador are frequently kicked out of their homes,” said Nóchez, who also reports on gender violence. To survive, many have to work in the streets as prostitutes, and this creates an additional layer of stigma because “their clients fear being exposed as ‘that’ type of client.” This vulnerability is only compounded by the fact that the Salvadoran transgender population has the highest rates of HIV in the country—two out of 10.

An analysis done by civil society organizations estimated that around 500 LGBTQ people had been killed since 1999. In 2016, Reuters reported that 25 LGBTQ people were killed in that year alone. In a country with a population roughly surpassing six million, these numbers are almost on par with the United States, which recorded death of 29 transgender people in 2017, according to advocates.

In a country where, according to the Pew Research Center, more than 60 percent of the population considers society should reject homosexuality, where women can be imprisoned for having a miscarriage, and where one of the political parties contending for the presidency (Vamos) crusaded against anything related to LGBT rights, some consider Bukele’s lukewarm position is foremost a political calculation. The new president is just conforming to the status quo and tiptoeing around this issue to avoid antagonizing a sector of society adamantly against granting rights to the LGBTQ community.

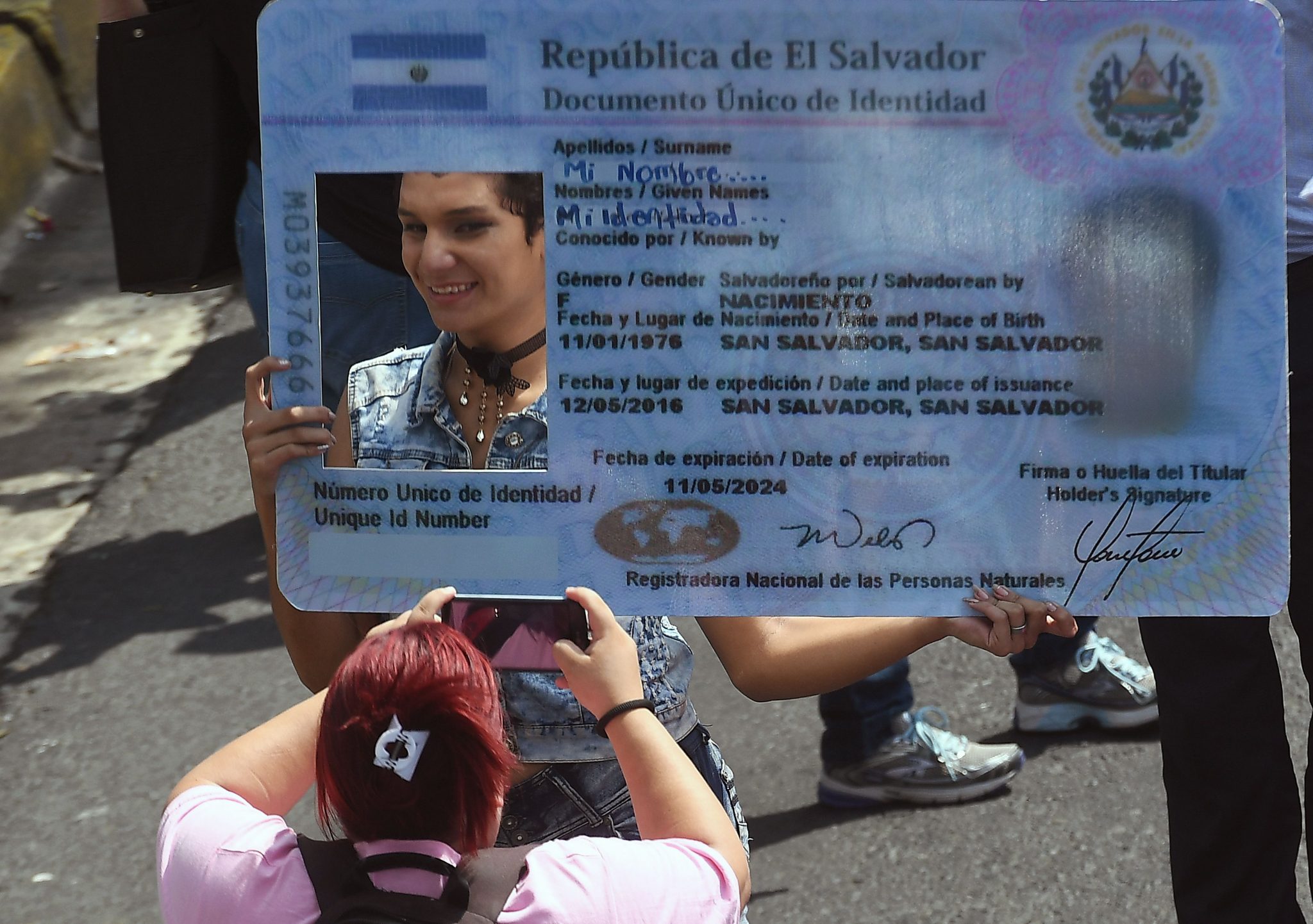

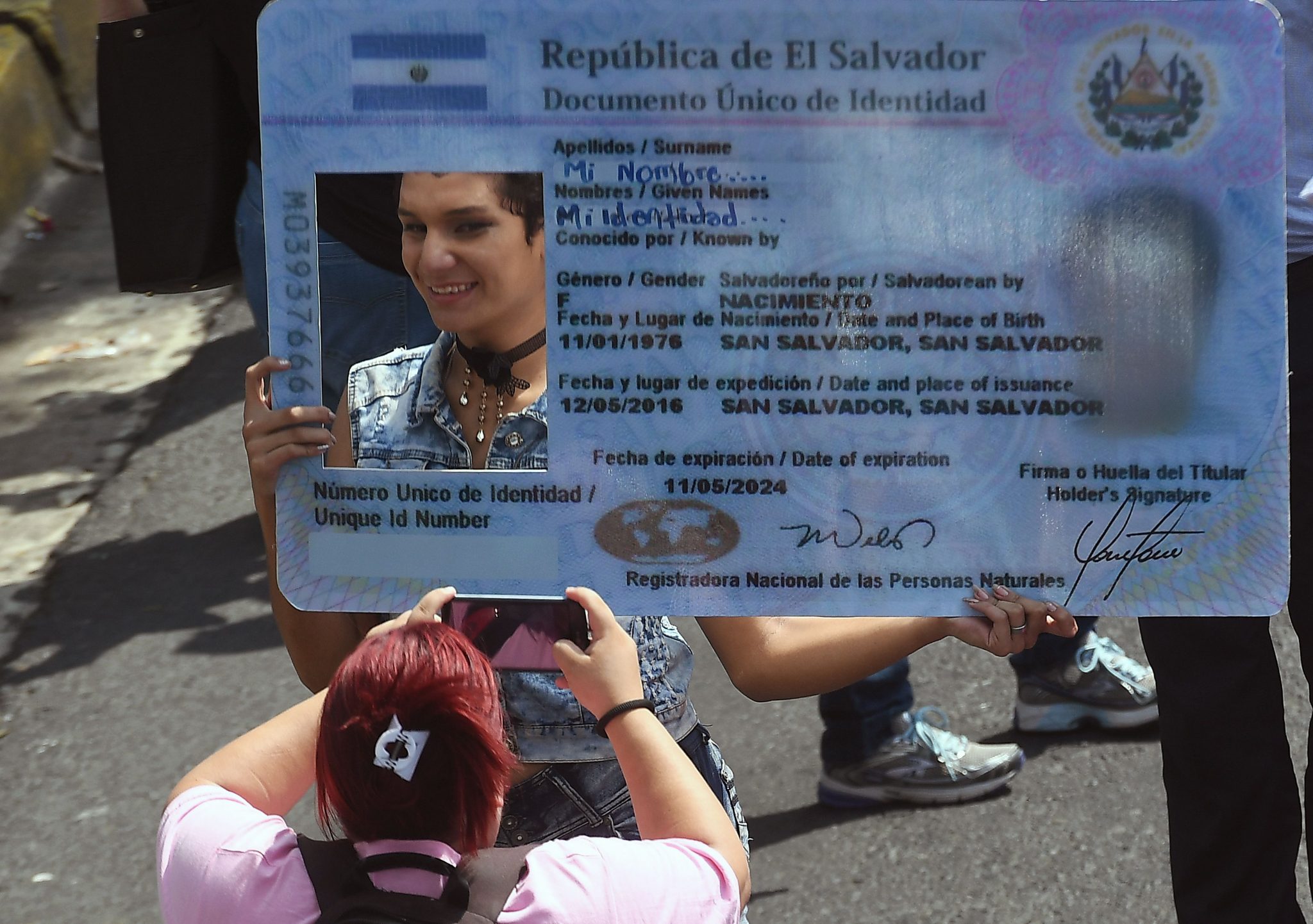

Activists participate in a march against homophobia on May 17, 2018 in San Salvador. (Photo by Marvin Recinos/AFP/Getty Images)

Researcher Vaclav Masek thinks of Bukele as an “opportunist,” and said he was probably being strategic.

“There is probably a core group of supporters who voted for Bukele, young Salvadorans, who would probably be dissuaded of his validity or his legitimacy as a candidate if he were to be outspoken or in favor of minority rights,” said Masek, who investigates democratic transitions in Central America.

Bukele won without the support of the two political parties that emerged out of the civil war from the 1980s and have dominated Salvadoran politics ever since. Perceived by voters as an anti-establishment outsider, Bukele campaigned hard against corruption and effectively portrayed himself as belonging to a political platform without such a loaded past, the small right-wing party known as Great Alliance for National Unity (GANA).

But in reality, Bukele’s political career was launched in 2012, when he was elected mayor of Nuevo Cuscatlán for the historically leftist Farabundo Martí National Liberation Front (FMLN). Three years later, he was voted mayor of San Salvador, the country’s capital, for the same party. Then, in 2017, the party’s ethics committee expelled him, allegedly after he threw an apple at a fellow congresswoman.

In 2014, when he was voted mayor of San Salvador, Bukele told the LGBTQ community he was committed to protecting their rights, Nóchez recalled. In November of that year, Bukele was recorded talking to a group of LGBTQ advocates. In the video, he tells them he is an ally, that he is convinced discrimination stems from ignorance and that he wants to be “on the right side of history.”

Regardless of who would have won, a Salvadoran LGBTQ organization found the elections presented an adverse scenario for queer rights, pointing to the absence of proposals in favor of the acknowledgment, protection and social inclusion of LGBTQ people. The exception came from the incumbent FMLN, who in 2010 created the Bureau of Sexual Diversity within the Ministry of Social Inclusion, from where timid attempts have been made to advance the queer agenda in the public sphere, and whose candidate promised to continue with the work done by the Ministry.

Notwithstanding the current situation, El Salvador‘s queer community is mobilizing. In June of 2016, more than a dozen social organizations announced the creation of the LGBTI Federated Association, an umbrella movement to help them gain political clout, fight against threats and create an observatory to systematize human rights violations.

However, in a country where being queer is potentially life-threatening, the federation is not really pushing to legalize same-sex marriage nor adoption for same-sex partners—flagship issues in the rest of the world. Instead, activist William Hernández told El Faro back when the federation was born, they are focused on protecting lives.

“What use is getting married if they are still killing us?” Hernández said.

***

Emily Corona is a digital intern at Futuro Media. She is a journalist and translator from Mexico City, pursuing a master’s in journalism and Latin American and Caribbean studies at NYU. She tweets from @daminijo.