Members of the Jejyty Miri community with the Espíritu Santo Team. Front row left to right: Maricana Araujo, Sister Mariblanca Barón, Sabino Piris, Aníbal Alfonso. (Photo by William Costa)

By William Costa

ASUNCIÓN, PARAGUAY — In early May, the Jejyty Miri Indigenous community in Paraguay received the good news they’d been waiting for. After three years of struggle over their 500-hectare territory near the town of Itakyry in the department of Alto Paraná, they won the right to return to the land they claim is their ancestral territory.

“After going through so many difficulties, hearing this decision makes us very happy,” Marciana Araujo, a member of the community, said. “It’s incredibly important. It means we have the possibility of going back.”

The Jejyty Miri community’s struggle for land is by no means unique among Paraguay’s roughly 500 Indigenous communities. A 2015 report from the United Nations special rapporteur on the rights of Indigenous peoples states that in addition to the 134 Indigenous communities that are entirely landless, 145 communities face problems related to the possession of their territories, such as ownership conflicts with business enterprises. Few of these communities manage to win their battles in the courtroom as the Jejyty Miri has done, however.

The Jejyty Miri community, who are part of the Ava Guaraní Indigenous people in eastern Paraguay, won their case with the help of an organization run by nuns. The Espíritu Santo Pastoral Mission has won land rights cases for about 30 Indigenous communities involving more than 25,000 hectares of land, according to Sister Mariblanca Barón, a founding member of the organization.

“We have an efficient lawyer, and we, the nuns, are good at what we do, too,” Barón said. “Those communities have the deeds in their hands.”

Lawyer Aníbal Alfonso delivers the news to members of the Jejyty Miri community that they have won their legal battle. (Photo by William Costa)

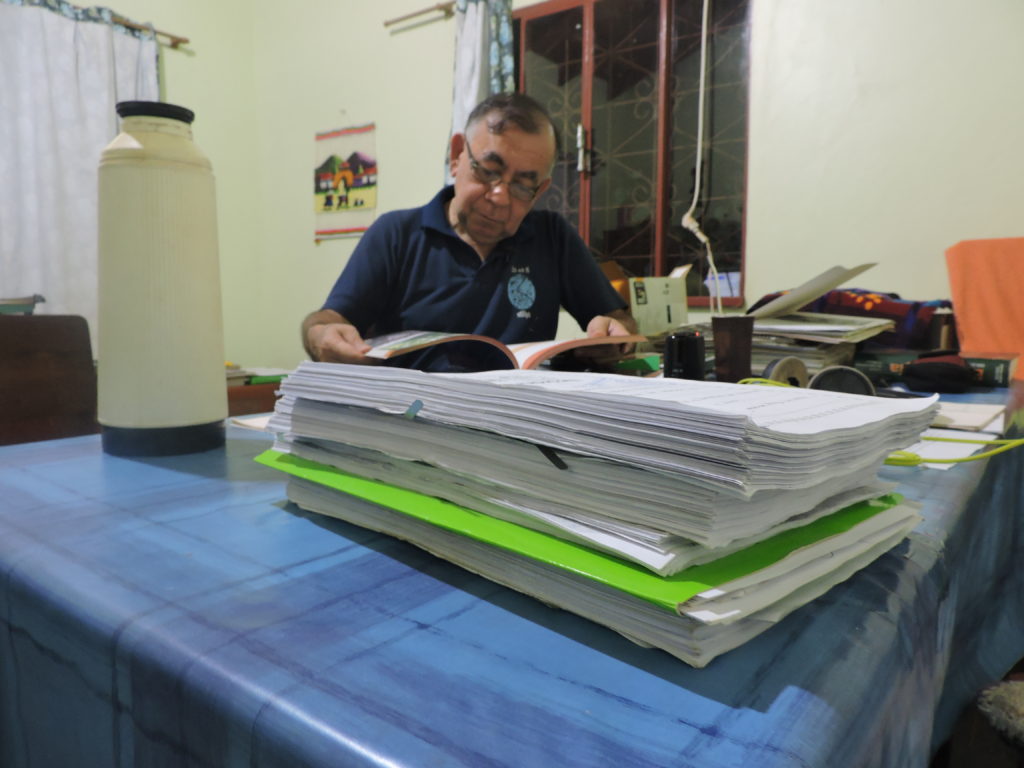

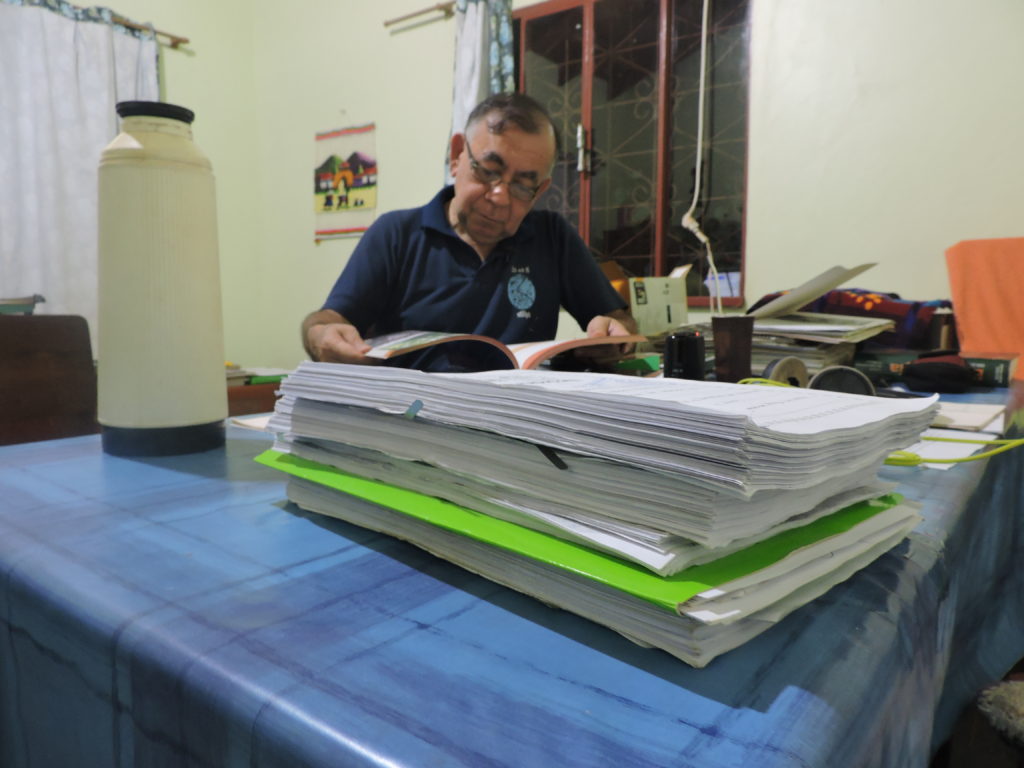

For more than 40 years, the nuns at the mission have collected records and legal documents related to the Ava Guaraní people, helping them win land rights cases and amassing an enormous archive of evidence of their legal land rights. Aníbal Alfonso, the mission’s lawyer who represented the Jejyty Miri, used this archive to piece together a five-tome, 500-page dossier to defend Jejyty Miri’s claims over its land.

“This is the center of it all. This is our laboratory,” Alfonso said of the archive, located in the small town of Nueva Esperanza. “Here, we study the documents and see what we have to work with. In the case of Jejyty Miri, we have very strong proofs. There’s a lot of documentation.”

The dossier Alfonso created includes photos, letters from public ministries and contracts. To the soy farmers fighting against Jejyty Miri, the 500 hectares of disputed land represent money—specifically $6 million. But to the Jejyty Miri, the land has more than economic value.

“For the community, alongside what it represents economically, it also has an affective, emotional value,” Alfonso said. “It is the source of their way of life, of their culture. If they are stripped of their land, of their territory, as so many other communities have been, they also lose their customs, their traditions.”

Aníbal Alfonso goes over the case dossier. (Photo by William Costa)

For the Jejyty Miri, the trouble began in 2016 when a conflict with a Brazilian soy farmer erupted over ownership of the lands traditionally inhabited by the community. The Indigenous group suffered repeated instances of threats and intimidation, which culminated in a violent eviction from the territory in early December 2017.

“They burnt our homes, and they almost burnt my children who were inside,” Araujo said.

Gunmen allegedly fired on the Jejyty Miri, hitting Araujo’s husband, Sabino Piris, who is a leader in the community. The assailants then allegedly burned their homes and used bulldozers to destroy their crops. The Indigenous families initially resisted but were soon overwhelmed.

One of the main causes of Indigenous land rights conflicts in Paraguay is the sustained boom in soy farming, which started in the 1960s, according to Luis Rojas, an economist researching rural development in Paraguay. The purchase of enormous swathes of land —using both legal and illegal means— by select, wealthy groups has dramatically increased the area employed for intensive soy cultivation from 1,200,000 hectares in 2000 to almost 3,600,000 at present. This trend has largely contributed to Paraguay’s status as the most unequal country in the world in relation to land ownership, according to the World Bank.

Soy fields near the Jejyty Miri land. (Photo by William Costa)

“This skewed distribution of Paraguay’s land is a source of permanent conflict, a conflict that wages between the powerful mechanized agriculture sector on the one hand and the Indigenous and peasant farmer sectors on the other,” Rojas said.

The virgin lands of eastern Paraguay have now been almost entirely incorporated into the soy and cattle-ranching sectors, with only about 10 percent of the once vast Atlantic Forest of the region left. As a result, industrial farmers have largely turned their attention to areas held by other groups, such as Indigenous peoples, in order to further the expansion of the green sea of soy.

Farmers have frequently taken over Indigenous land by claiming they have deeds to the land. This is what happened to the 500-hectare territory of the Jejyty Miri, the lawyer Alfonso said. After the Jejyty Miri were evicted from their homes, they were forced onto a 15-hectare section of the territory. The soy farmer defended himself by saying the Indigenous community always lived on the 15-hectare section, but not on the rest of the territory.

“Indigenous communities are vulnerable,” Alfonso said. “They don’t have many ways of defending themselves. The soy farmers know that.”

The soy farmer who took over the Jejyty Miri land exploited a bad land deal made by the state in 1996. The government bought the 500 hectares for the Indigenous group, but they purchased it from someone who did not have the authority to sell it, according to Óscar Ayala, executive secretary of the Paraguayan Human Rights Coordination Group (CODEHUPY). The deal came back to haunt the community years later as they fought to stay on the land.

“Once again, we are seeing a case where corruption has produced conditions in which the rights of an Indigenous community have been violated,” Ayala said in an interview with the La Unión radio station.

The Paraguayan Constitution establishes the right of Indigenous peoples to communal ownership of their lands and prohibits their removal from these areas without their direct consent. Additionally, Paraguay is party to several international treaties that act to protect Indigenous land rights. The state’s refusal to guarantee the territory of Jejyty Miri was a grave violation of the legal guarantees held by Paraguay’s Indigenous population. The state’s actions are hardly surprising, however. Historically, authorities in Paraguay have strongly favored the interests of powerful landholders over Indigenous communities.

“From a legal perspective, the state has all the necessary conditions to fully recover ownership of the land and to finalize the deeds for this Indigenous community,” Ayala said.

The state still did not act, however, forcing the Jejyty Miri to embark on a three-year legal battle, with Alfonso and the nuns at their side. In the end, after a successful appeal by Alfonso, the court declared that the land was the rightful possession of the Jejyty Miri community.

“We’ve won the case. We’ve categorically won,” Alfonso said. “They’ve awarded us 100 percent of what we were asking for.”

Following the announcement of the legal decision, members of the Espíritu Santo Pastoral Mission traveled to the 15-hectare area, where the community is living, to share the news. After a ceremony on June 19, the Indigenous families will return to their ancestral 500-hectare home. For community members like Araujo, the homecoming is not just a victory for them, but also for their ancestors.

“Our grandfathers and grandmothers are in the cemetery,” Araujo said. “We couldn’t leave them behind.”