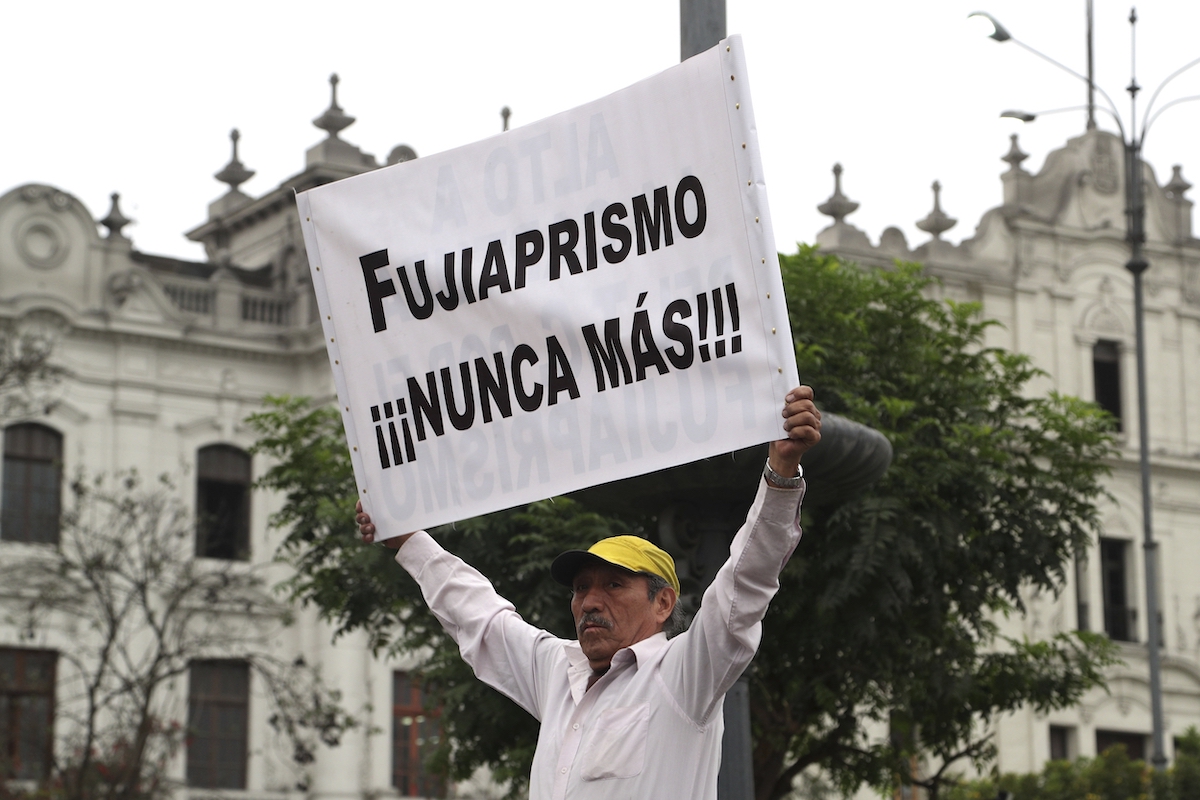

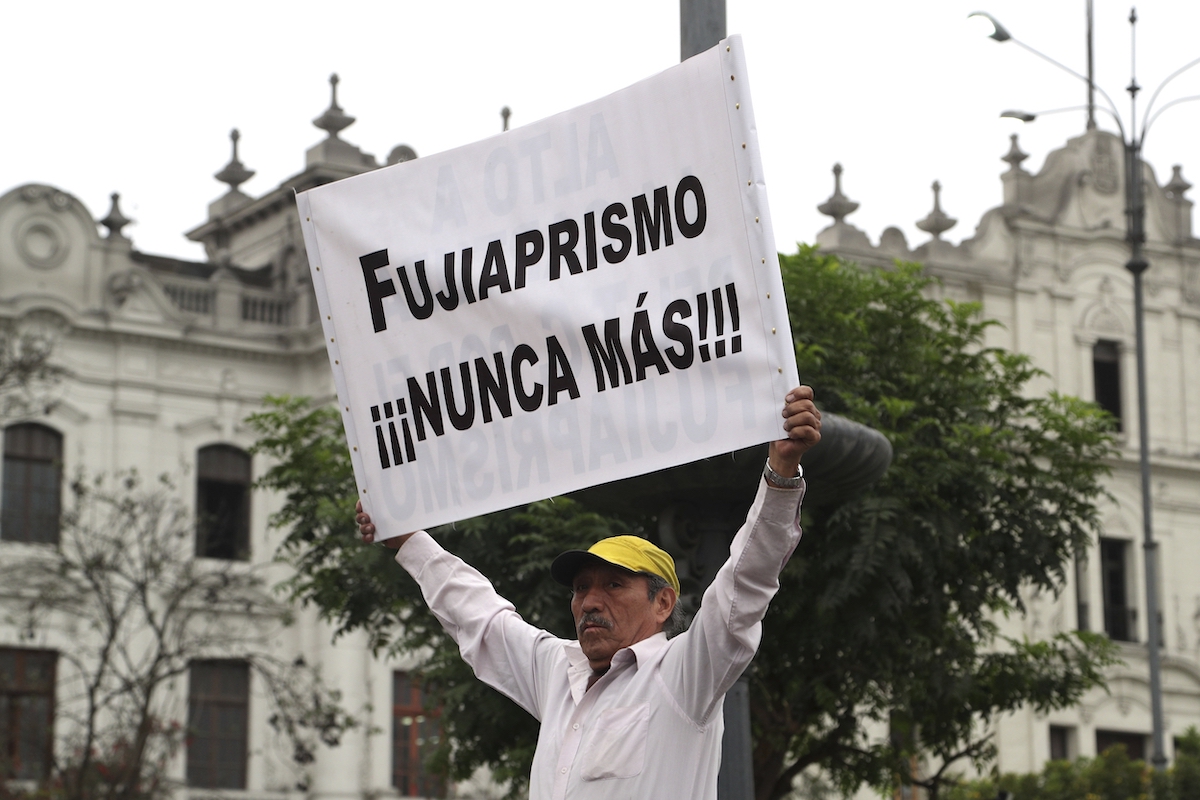

A supporter of Peru’s President Martin Vizcarra holds the Spanish message: “Fuji-Aprismo never again!,” referring to the Fujimori administration and the opposition political party Apra, during a rally to show support for Vizcarra after he dissolved Congress, near both Congress and the presidential palace in Lima, Peru, Thursday, Oct. 3, 2019. Peru is in the throes of its deepest constitutional crisis in nearly three decades as Vizcarra and the opposition-controlled congress engage in an acrimonious tug of war over who should lead the South American nation. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia)

By CHRISTINE ARMARIO, Associated Press

LIMA, Peru (AP) — Inside a colonial-era mansion that has seen better days, leaders of Peru’s Fuerza Popular movement gathered for an urgent meeting Thursday, scrambling for ways to save their party’s once-dominant place in politics.

President Martín Vizcarra dissolved the congress early this week and called new elections after a dispute with lawmakers over anti-corruption efforts, unilaterally eliminating Fuerza Popular’s hard-won majority in the legislature. Meanwhile, the party’s leader was already sitting behind bars at a women’s jail filled with drug traffickers and petty thieves while she is investigated for corruption allegations.

The dissolution of congress has plunged Peru into its deepest constitutional crisis in nearly three decades, and some think it may be the start of a final, bleak chapter for the country’s most prominent political dynasty. When the legislature was last shut down in 1992, strongman Alberto Fujimori sat in the presidential palace calling the shots. Fast forward 27 years, and now it is the party led by his cherished eldest daughter that is being kicked out.

When Fuerza Popular’s leaders stepped outside their headquarters after their meeting, they encountered a cruel realty: Much of Peru doesn’t love them anymore, according to opinion polls and hostility expressed on the streets.

A rally by a small band of Fuerza Popular supporters demanding justice for jailed party leader Keiko Fujimori drew an angry response from one passer-by. “You all are going to hell!” Susana Valverde shouted.

The political phenomenon known in Peru as “Fujimorismo” has seen wild ups and downs but it has always managed to rebound. This time might be different. If new legislative elections are held in 2020, as Vizcarra plans, the party will almost certainly lose its majority in congress.

“Fujimorismo has been in a death spiral,” said Steven Levitsky, a Harvard University political scientist. “It’s going to get pummeled in the election that comes. This is a pretty dramatic decline.”

The political dynasty began in 1990 when Alberto Fujimori, the Lima-born son of Japanese immigrants, won the presidency promising to usher Peru into a new era of progress. His pro-business policies, hardline anti-crime initiatives and social programs made him popular with droves of Peruvians, Nancy Ríos among them.

FILE – In this July 8, 1990 file photo, Peru’s newly elected President Alberto Fujimori waves to supporters, accompanied by his wife and children, from left, Susana, Hiro Alberto, 13, Kenji Gerardo, 9, Sachie Marcela, 12, and Keiko Sofia, 15, in Lima, Peru. The Fujimori political dynasty began in 1990 when Alberto Fujimori, the Lima-born son of Japanese immigrants, won the presidency promising to usher Peru into a new era of progress. (Alejandro Balaguer/AP Photo, File)

“When he arrived, this country was totally destroyed, worse than Venezuela. With him we found peace, economic stability,” Ríos said.

But after a decade in office, Fujimori faxed in his resignation after fleeing to Japan while facing imminent removal by an opposition-controlled congress. In 2005, he was captured in Chile and extradited to Lima, where he was eventually sentenced to 25 years in prison for human rights abuses, corruption and sanctioning death squads.

The former mathematics professor is still serving time for his role in the killings of 25 people, including an 8-year-old boy, during his administration.

FILE – In this Oct. 25, 2013 file photo, jailed former President Alberto Fujimori attends his hearing at a police base on the outskirts of Lima, Peru. In 2005, Fujimori was captured in Chile and extradited back to Lima, where he was eventually sentenced to 25 years for human rights abuses, corruption and sanctioning death squads. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia, File)

Still, there were plenty of Peruvians willing to forgive Fujimorismo. Keiko Fujimori carried her father’s torch, expanding the party’s base and sought to forge a gentler, kinder image of the movement. By many accounts, she largely succeeded.

“I’ll support the party until the day I die,” said Ríos, a housewife.

In 2011, Keiko Fujimori finished second in Peru’s presidential election. Five years later, she lost again in a razor-thin vote, coming within less than a half percentage point of defeating economist Pedro Pablo Kuczynski. And Fuerza Popular captured a majority in congress.

FILE – In this May 31, 2016 file photo, confetti rains on presidential candidate Keiko Fujimori and her supporters during a campaign rally in Lima, Peru. Keiko Fujimori carried on her father’s torch, expanding the party’s base and trying to forge a gentler, kinder image of the movement, but lost both her attempts at the presidency. (AP Photo/Silvia Izquierdo, File)

But it’s been downhill from that high point.

Constantly butting heads with Kuczynski, and later Vizcarra, its legislators have earned a reputation as hardline obstructionists for blocking initiatives popular with Peruvians aimed at curbing the nation’s rampant corruption.

“This was a party behaving less like a political party and more like a mafia,” Levitsky said.

Late last year, Keiko Fujimori was ordered jailed as prosecutors investigate accusations she laundered money from the giant Brazilian construction company Odebrecht for her 2011 presidential campaign, a big comedown just a few short years after coming so close to winning the presidency.

FILE – In this Oct. 17, 2018 file photo, Keiko Fujimori, the daughter of Peru’s former President Alberto Fujimori, and leader of the opposition party, enters to the courtroom wearing a chest vest that reads in Spanish: “Detained” during a hearing where she is appealing her detention as part of a money-laundering investigation in Lima, Peru. Keiko Fujimori’s detention marked the start of a new downfall for both the party and the woman who a few short years before was on the verge of the presidency. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia, File)

Legislators whose seats are being threatened by Vizcarra’s order dissolving congress say they are prepared to fight, even as polls say most Peruvians want them out. They are devising a legal challenge in hopes of keeping congress open and avoiding a 2020 election.

“We’re not going to permit any situation in which the left takes the majority,” said Luis Galarreta, one of the lawmakers.

Party members call the president’s action a “modern coup” and say they are victims of a witch hunt.

Police launch tear gas at supporters of President Martin Vizcarra to keep them from forcibly entering Congress after the president dissolved the legislature in Lima, Peru, Monday, Sept. 30, 2019. Vizcarra dissolved congress Monday, exercising seldom used executive powers to shut down the opposition-controlled legislature that he accuses of stonewalling attempts to curb widespread corruption. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

Legislator Juan Carlos González contends news media are spreading a false narrative that the party has lost public support. He said over 2,000 people turned out at a recent town hall-style meeting he hosted.

“The party has been declared dead before,” he said. “We’re not going to stay quiet.”

Levitsky estimates Fujimorismo maintains 10% to 15% public support, and believes that although weakened, the party won’t entirely go away, particularly if it is to forge a partnership with other right-leaning groups.

But for Peruvians like Maria Quispe, who works at a restaurant in a poor neighborhood now filled with Venezuelan migrants, the public’s relationship with Fujimorismo is irreparably broken. She voted for Alberto Fujimori in 1990, but said she cannot bring herself to vote for anyone now from the movement.

“They had a chance, but kept doing what was in their own self-interest,” she said. “There’s no way at this point that everything can be forgotten.”