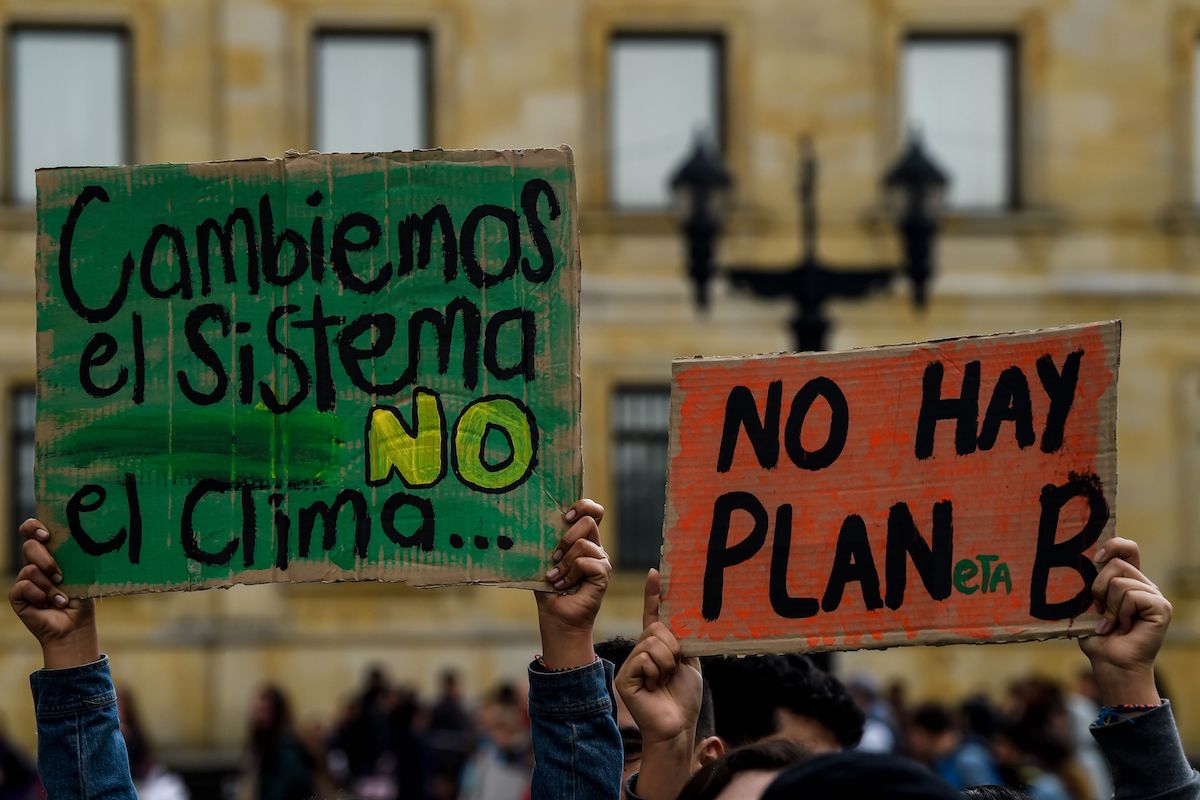

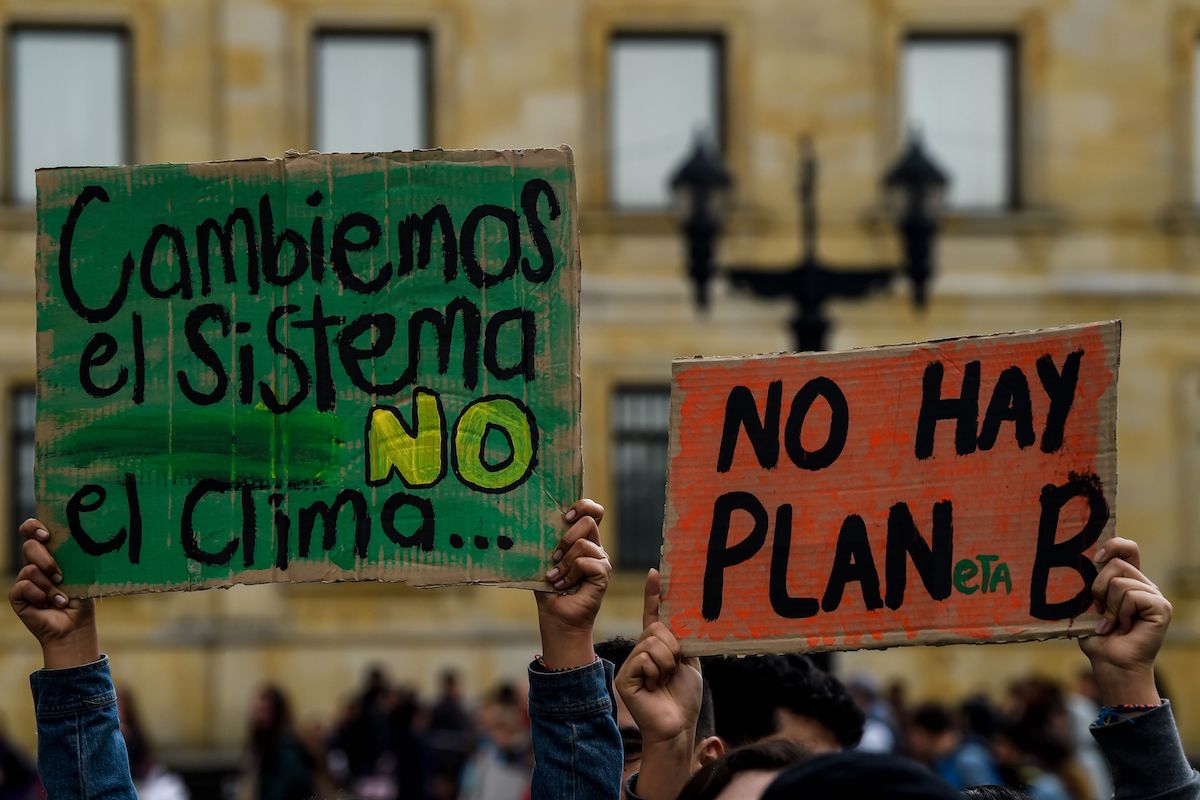

People hold signs reading “Let’s change the system, not the weather” (L) and “There is no plan(et) B” during a protest at in Bogotá, Colombia, on September 20, 2019. (Photo by JUAN BARRETO/AFP via Getty Images)

By Fátima García Elena, Nottingham Trent University

Climate change, plastic pollution, rising sea levels. Environmentalists in developed countries are calling for action on the planetary emergency. But when environmentalists are brave enough to speak out in places like Barrancabermeja, Colombia, they’re often protesting against very local problems. Lack of sanitation, contaminated water, deforestation for palm oil—degradation of the local environment and the direct threat to human health are closely linked and clear to people here.

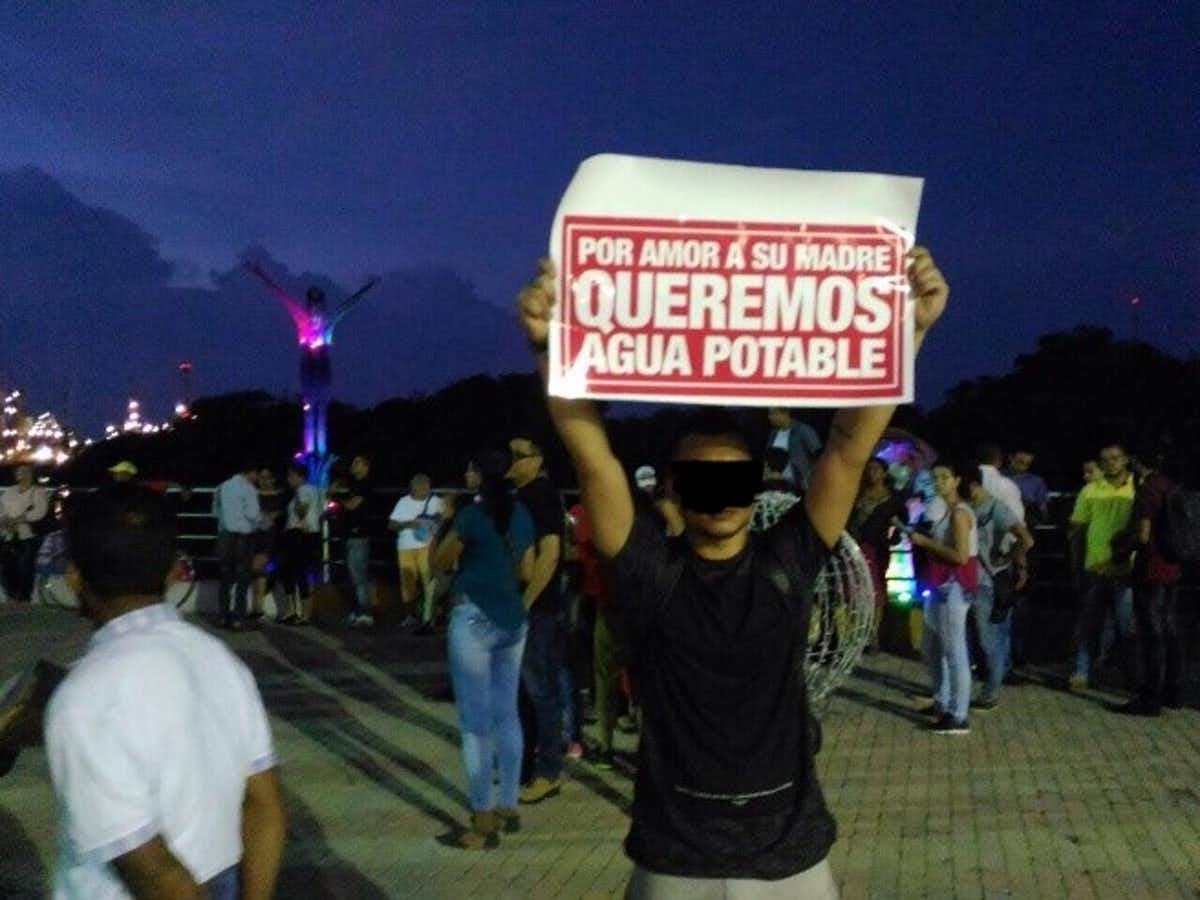

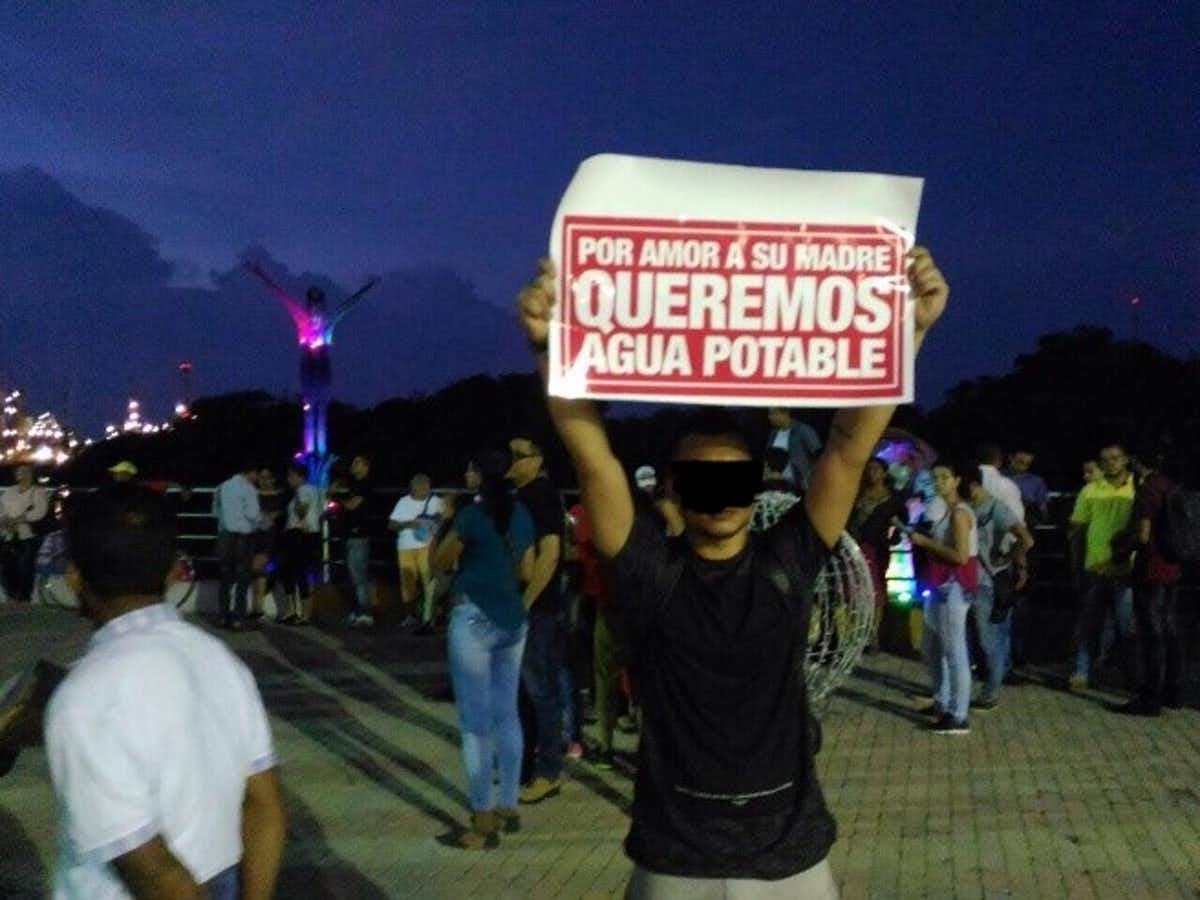

Barrancabermeja hosts Colombia’s largest petroleum refinery, which has been operating for just over 100 years. Over that time, local industries have contaminated natural water courses with heavy metals, which has been absorbed by the soil and the surrounding vegetation that local cattle eat, which have also showed high levels of heavy metals. The plumbing that is supposed to supply the city with fresh water doesn’t reach all areas, meaning that some places lack running water and sewage treatment. This situation has motivated passionate environmental protests.

But these are nothing new. In the general city strike of 1963, pollution and access to water were two of the main issues. Safe drinking water was also a recurrent theme throughout the city strikes of the 1970s. Even during the worst of the Colombian conflict from the 1980s to the early 2000s, the people of Barrancabermeja were brave enough to continue protesting for the right to clean water, and they still do today.

Here in the heavy industry heartland of Colombia, environmentalism has old roots and has endured through decades of violence and intimidation. In order to understand how street movements can prosper, it’s worth asking how people here have maintained popular concern for the environment over so many years and under so much pressure.

Local Danger, Global Solidarity

Environmental protests in developing countries in Asia, Latin America, Africa and the Caribbean can be dangerous. These regions are often collectively called the Global South. Of the 20 countries with the most murders of environmental activists in 2018, 19 are considered to be part of the Global South. The only exception is Ukraine, which ranks 10th with three deaths. Philippines has more registered murders than any other, with 30 killed in 2018. But it’s closely followed by Colombia, with 24.

A protest for safe drinking water in Barrancabermeja, January 2018. The sign reads: ‘Out of love for your mother, we want potable water’. (Fátima García Elena, Author provided)

These are only official numbers that don’t account for disappearances or unregistered assassinations. They also do not accurately capture the atmosphere of persecution and abuse that torments activists. In Barrancabermeja, environmental leaders are slandered, bullied and threatened. Many have had to abandon their home and seek political asylum abroad.

The environmental movement gained the support of millions of people in 2019. Extinction Rebellion and the climate strikes have mobilized people who are concerned about climate change but live lives of relative affluence, far from the front lines of battles over fresh water and clean air. This doesn’t diminish their role or invalidate their cause. Standing in solidarity with people less fortunate and calling for coordinated, global action is essential, and it’s great to see the media covering it. But the experiences of people protesting in Barrancabermeja need to be heard too.

It’s important to acknowledge the differences between environmental struggles around the world to address the diverse challenges of failing ecosystems and value the contributions of all towards finding solutions. Raising awareness of rising temperatures and shifting coastlines is important—the climate crisis is after all a global problem. But the risks aren’t evenly distributed, and the effects are more localized and pressing for some. Media scrutiny of the powerful in places like Barrancabermeja could raise pressure to protect the brave work of activists there.

Let’s show that environmentalism is both global and local, and responding to threats both present and future. Let’s show solidarity with the people in Barrancabermeja.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.