(Richard Tsong-Taatarii/Star Tribune via AP)

Versión en español aquí.

Repealing the 14th Amendment, or at least its guarantee of birthright citizenship, has long been the ultimate fantasy of American nativists, from Stephen Miller to Ann Coulter to Joe Arpaio. You can understand why. Every 30 seconds a Latino in the United States turns 18. If they were born in the United States, that means they can now vote in the United States. Odds are pretty good they won’t feel too kindly about the people who wanted to strip them of citizenship in the country of their birth. But though the xenophobes in power wage war on mixed-status families via deportations, public charge rules, and messing with the U.S. census, repealing the 14th Amendment remains a pipe dream for the Latino-haters. Even in the Trump era, it seems that the 14th Amendment and its guarantee of birthright citizenship is one constitutional protection that Latino communities can count on.

Yet the protections and rights the 14th Amendment guarantees to the children of Latino immigrants were not born from the struggle for immigrant rights. The 14th Amendment, written in the immediate aftermath of the Civil War to preserve the new freedoms of former slaves, is the result of an even longer and more brutal struggle in American history: the fight for racial justice. That fight has been principally been waged by Black Americans, to the benefit of every racial minority group. The 14th Amendment is just one example among many of how Latinos have benefited from the advocacy and struggle of Black Americans.

Non-Black People of Color in America, especially those of us who are immigrants or descendants or recent immigrants, often feel like we don’t fit into the Black and White racial binaries of American history. Latinos in particular can feel somehow neutral, even alienated, from the struggle for racial justice in America, especially when it comes to fighting for Black people. Why should we who just got here, feel responsible for dealing with the legacy of wrongs committed in America long before our parents or grandparents crossed the border?

These questions are more relevant than ever. I write as another American city burns in an insurrection, sparked by the murder of George Floyd but a predictable outcome of long-term abuse by law enforcement of Minneapolis’ Black community. Where should Latinos stand in such times? Some will no doubt stand with the police, with anti-Blackness, and ultimately with white power in America. Many more will just try and stay neutral or silent, seeing just another Black-White confrontation that has little to do with us. That would be a tragic mistake.

The reality is the struggle for racial justice in America is not just a Black-White struggle, though it is undeniable that Black people have been fighting it the longest. The struggle for racial justice is what will ultimately shape Latinos’ place in America. The victories won in that struggle are the foundation of every Latino life in this country, a foundation set by Black people and which Latinos today too often take for granted. As the Guatemalan-American writer Héctor Tobar put it in his reflection on the assassination of Martin Luther King: “My family’s success in this country became associated in my mind with the blood and the sacrifice of black people… I think every Latino kid grows up this way, in proximity to the drama of American history and its assorted players, trying to figure out where he fits in.”

Today, Latinos must choose what part we will play in this latest chapter of America’s struggle for racial justice. I hope we will choose to reject neutrality and fight for racial justice. In order to do so Latinos must fight against anti-Blackness.

We must begin by fighting anti-Blackness in our own communities. Too often we have brought with us to the United States the anti-Black prejudice that are prevalent across Latin America, which was shaped the same structures of slavery and European colonialism as the United States. From Argentina to Mexico, Latin American societies are deeply racist against people of African origin. These very same societies have celebrated and worshipped whiteness for centuries at the expense of our fellow Black Latin Americans. If we can’t confront that reality, how can we begin to confront what is in front of us right here in the United States?

Non-Black Latino communities in this country also too often embrace the anti-Black attitudes, stereotypes, and worldviews we find in the United States as part of a process of assimilation. This is a well-beaten path in U.S. immigrant history. Many immigrant groups have sensed in anti-Blackness an opportunity to assimilate into whiteness, or at least move into closer proximity with it. American Latinos, as the largest ethnic minority group and the largest share of today’s foreign-born population in America, must not follow this path. It would be a disaster for the cause of racial justice if we did so, not to mention a compromise with the same ideology of white supremacy that has motivated such horror on our people, from the Porvenir massacre over 100 years ago to the El Paso massacre just last year.

There is a better path to take. It may at times be harder, but it is the only one that takes to where we truly want to go: the path to a genuinely multiracial democracy in America. And that is a path that has been established, carved out, defended by Black people. It is Black people who have always held America to task for failing to live to its founding ideals. As Nikole Hannah-Jones wrote in her essay for the 1619 Project: “Black Americans have been, and continue to be, foundational to the idea of American freedom. More than any other group in this country’s history, we have served, generation after generation, in an overlooked but vital role: It is we who have been the perfecters of this democracy.”

Black leaders, activists, writers, and thinkers have left a blueprint for every American of Color on how to be American in an America that does not treat you as an equal, as well as how to fight for so that it someday might. Latinos should, of course, be proud of our own part in the struggle for racial justice in America. As a Mexican-American, I personally find pride in the fact that slaves who fled bondage in America found freedom in Mexico and that the Victory at Puebla set back not just the French but also the Confederates.

Latinos should celebrate that the 1947 Méndez v. Westminster decision set the precedent for Brown v. Board of Education.

This reminds us that in the struggle for racial justice, Black people and Latino people share a common fate, as the COVID-19 pandemic’s disproportionate impact on both Black and Latino communities has shown. Yet Latinos must also recognize that we have, for the most part, simply followed in Black people’s footsteps when it comes to the treacherous path towards a more just America.

Today, Latinos must continue to follow Black people’s lead. That means Latinos must demand justice for George Floyd, for Ahmaud Arbery, for Breonna Taylor. Latinos must say Black Lives Matter, not just on social media, but at our dinner tables and to our families. It means mobilizing Latino political power in solidarity with Black struggles, following the example of Latino leaders such as Julián Castro and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who have both unapologetically embraced the cause of ending police violence. It means recognizing and supporting Black Latinos and the full diversity of Latin American peoples, including criticizing our countries of origin when they mistreat Black people. For example, as a dual U.S. and Mexican citizen, I have a duty to criticize the Mexican government’s abuse of African migrants, part of Mexico’s shameful complicity with the Trump administration’s anti-immigrant policies. It means condemning a U.S. President who has openly incited violence against Black people in Minneapolis, something that Latinos who remember El Paso should recognize the danger of. This is just a small part of the debt that Latinos owe Black people, for it is Black people and their sacrifices that have created the very possibility of an America in which we too can belong.

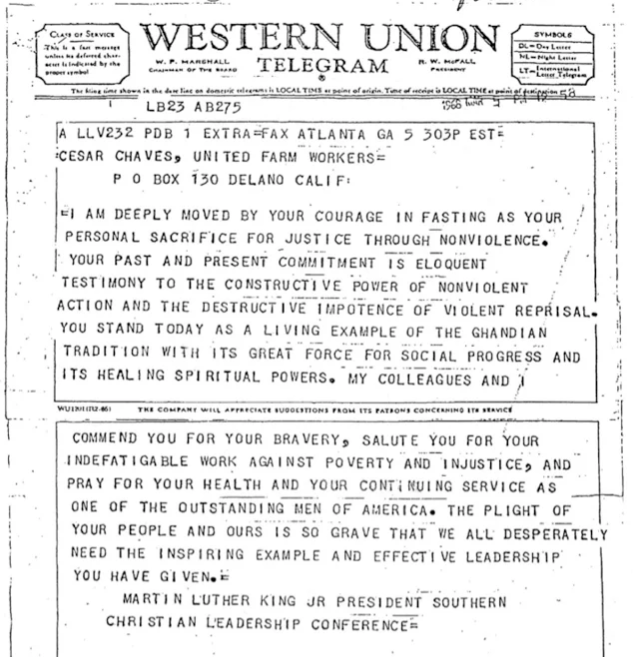

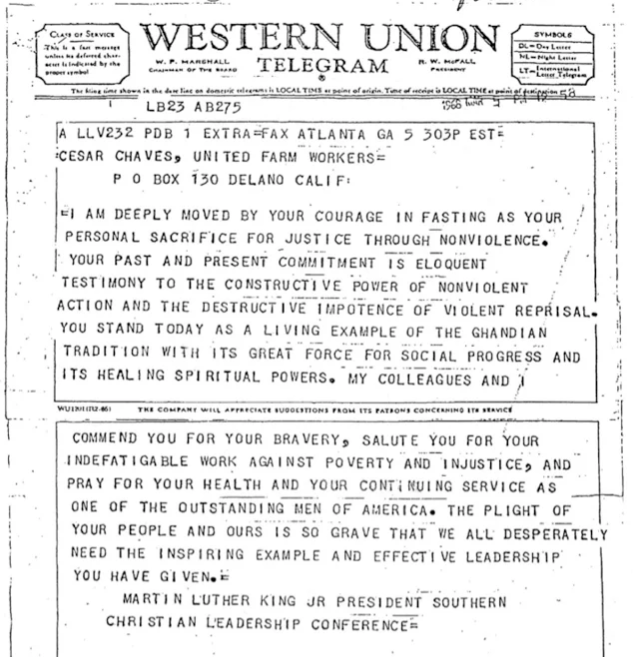

In 1968, just weeks before he would be assassinated, Martin Luther King wrote to César Chávez, the leader of the United Farm Workers wasin the middle of a 25-day fast for nonviolence.

“The plight of your people and ours is so grave,” King wrote in the telegram to Chávez, “that we all desperately need the inspiring example and effective leadership you have given.”

Via UFW

This acknowledgment by King of a shared struggle confirms that throughout American history, Latinos have benefited from the fight for racial justice, enjoying rights won for us by the struggles of Black people. Today, as Black people again face an onslaught of nightmarish violence, heartbreak, discrimination, and loss, it is time for Latinos to return the favor.

***

Antonio De Loera-Brust is a Mexican-American writer, filmmaker, and former congressional and campaign staffer from Yolo County, California. He most recently served as a policy staffer on the Julián Castro and Elizabeth Warren presidential campaigns. He loves tacos, soccer, and the outdoors, and writes about diversity, farmworkers, and politics. You can follow him @AntonioDeLoeraB.

I’ve been reading essays on this site for sometime; this is by far the most substantive and insightful one I’ve ever read. You need to publish more that digs deep into contemporary issues to educate and inform all of us. Thanks

Thanks!

LMAO = YOUR SAD !! SO TAKE EVETYTHING AESY FROM LATINO’S AN BOW DOW TO BLACK AMERICA ?? HOW SICK

The author needs to learn history. He negates our own leaders who fought for our rights. And he seems to forget, or not to know, that we became US Citizens when the southwest became part of the United States, which was before the Civil War and the 14th Amendment. We also fought in that war, even though the history books erase it. And we set the legal precedent for Loving v Virginia with a case called Perez v Sharp. We also won the first school desegregation cases in the country, which set the precedent for Brown v Board. In fact the first civil rights cases Earl Warren ruled on were cases involving Mexican-Americans in California.

This article is a joke.

Exactly!!

Funny those Cival war pictures I didn’t see on Latina ,not one

Bingo! Guilt, Guilt….

When Thurgood Marshall and his team of Black Civil Rights lawyers were preparing to launch their assault on de jure school segregation Menedez vs Westminster School District was ONE of several key civil rights cases which Marshall studied or cited as precedents for the Brown vs Topeka landmark case; the late Willie Velasquez & Jose Angel Gutierrez met and consulted with Stokely Carmichael & H. “Rap” Brown of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as Velasquez & Gutierrez prepared to launch the Mexican-American American Youth Organization (MAYO); the NAACP Legal Defense & Education Fund were instrumental in the founding of the Mexican American Legal Defense & Education Fund (MALDEF) and the Puerto Rican Legal Defense &Education Fund (PRDLEF) – MALDEF & PRDLEF are powerful organizations who are allied with the LDF ; the Black Panther Party directly supported the founding of both Young Lords Organization (YLO) and the Young Lords Party (YLP) ; Latinx activists have joined Black Lives Matter activists in demonstrations and political organizing efforts – in turn Black Lives Matter activists have reached out in meaningful ways to support Latinx families in Vallejo and Phoenix who have lost their sons to police violence.; the previous items are historical and contemporary facts/examples of collaboration ; it is true that the Black Civil Rights Movements existed in parallel with Mexican-American and Puerto Rican Civil Rights Movements – sometimes they even worked in collaboration.

No you are the joke and you are the problem you’re exactly who this article is speaking to. You can’t circumvent history and create your own facts.

You are so delusional & confused. The war between the U.S & Mexico made the Mexican people of the southwest citizens, not else where. The truth is Mexicans & Native Indians are the same, & you guys were chased & killed out of this country. The Black man fought & is continuing to fight. Every right you have was created off the Blood, & Back of a Black. There was no rights for anyone except the settlers everyone else (Blacks & Whites) either was enslaved or killed. Black people fought for over 400 years, the civil war is how slavery was made illegal, but Blacks still didn’t have rights. Blacks are the reason you Mexicans can vote, & still be in this country, as I stated you guys didn’t fight for yourselves you were chased out, & you Mexicans sat on your ass in Mexico & in the Southwest while Blacks fought. Every time we accomplished something you guys would just the border & come over here to imitate us & reap the fruits of our labor. We fought for the right to vote, & now y’all get to vote. Blacks ended segregation, now y’all Mexicans are jumping borders left & right to come back to this country. The Mexican people have contributed nothing to society but the bandana. You guys let the Blacks do the dirty, & hard work. Blacks die for freedom & you guys reap the benefits. The Mexican race has never even created anything to help society. While the Black man has created everything from the lightbulb to the population of Earth. We are Gods chosen people, Blacks are the first humans to walk Earth. We’re God’s chosen people & your Mexican race has lived off our hard work long enough. One day you Mexicans are going to have to earn your way & contribute more to society besides the cheap labor you provide In the fields. You guys have gotten everything for free off our backs. Btw I read that little article on google about hispanics being forgotten in the civil rights movement & you literally plagiarized that whole article. Iaughed bc that article can only list 3 contributions from Mexicans. Lol… Your family is waiting right now for Blacks to protest again so that minorities can benefit, without having to contribute. You guys owe us your life & go tell your lying ass parent’s I said it. Tell them to tell you the truth, your people were chased out this country & Blacks fought for freedom which is why you’re America today. My ancestors did more for your family than y’all did for yourselves.

If you read the comment section and search it up you can actually see that there was a lot of Mexican American political movements all over the USA. Even martin luther king JR acknowledge that. You saying Mexicans are nothing but boarder hoopers and bring nothing to the USA really shows how racists you are. all the mostly Hispanic states are the ones that keep this country on his feet(California and Texas). Please stop being racists toward Mexican Americans, they fought for their rights as strong as blacks. Even know Hispanics are still the back bone of this country and still work stuff like plantation and hard labor jobs like construction. Also many go to college and get white collar jobs. Please stop building a stereotype that we are just plantation workers,etc. We are honest people with many small business all around the usa. Also a lot of the new world fruits and vegetables came from genetically engineer plants that people like the Aztecs made through selective breeding stuff like corn.

Also Here are a few comments that explain Mexican American contributions in politics

“The author needs to learn history. He negates our own leaders who fought for our rights. And he seems to forget, or not to know, that we became US Citizens when the southwest became part of the United States, which was before the Civil War and the 14th Amendment. We also fought in that war, even though the history books erase it. And we set the legal precedent for Loving v Virginia with a case called Perez v Sharp. We also won the first school desegregation cases in the country, which set the precedent for Brown v Board. In fact the first civil rights cases Earl Warren ruled on were cases involving Mexican-Americans in California.”

“When Thurgood Marshall and his team of Black Civil Rights lawyers were preparing to launch their assault on de jure school segregation Menedez vs Westminster School District was ONE of several key civil rights cases which Marshall studied or cited as precedents for the Brown vs Topeka landmark case; the late Willie Velasquez & Jose Angel Gutierrez met and consulted with Stokely Carmichael & H. “Rap” Brown of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as Velasquez & Gutierrez prepared to launch the Mexican-American American Youth Organization (MAYO); the NAACP Legal Defense & Education Fund were instrumental in the founding of the Mexican American Legal Defense & Education Fund (MALDEF) and the Puerto Rican Legal Defense &Education Fund (PRDLEF) – MALDEF & PRDLEF are powerful organizations who are allied with the LDF ; the Black Panther Party directly supported the founding of both Young Lords Organization (YLO) and the Young Lords Party (YLP) ; Latinx activists have joined Black Lives Matter activists in demonstrations and political organizing efforts – in turn Black Lives Matter activists have reached out in meaningful ways to support Latinx families in Vallejo and Phoenix who have lost their sons to police violence.; the previous items are historical and contemporary facts/examples of collaboration ; it is true that the Black Civil Rights Movements existed in parallel with Mexican-American and Puerto Rican Civil Rights Movements – sometimes they even worked in collaboration.”

Also many people invented the light bulb and revolutionized over the years. Stop making it seem like it’s a black invention. Stop being so racists is disguisting.

please stop being racists towards mexican americans and equating them to just cheap labor many mexican americans work constructions, carpenting, and other blue collard jobs which is honest work and there is nothing wrong with it. don’t equate us to that racists stereotype of being boarder hoppers that bring nothing to the usa which is not true. california and texas are the leading states when it comes to GDP and they are also the ones with the most hispanics. also people like the aztec(ancestor of many mexicans) brought new genetically engineered crops like corn that are heavily use today for many things like corn syrup. also mexican americans also helped in many political movements even people like martin luther king jr acknowledge that.

also here are a few comments explaining mexican american contributions.

“The author needs to learn history. He negates our own leaders who fought for our rights. And he seems to forget, or not to know, that we became US Citizens when the southwest became part of the United States, which was before the Civil War and the 14th Amendment. We also fought in that war, even though the history books erase it. And we set the legal precedent for Loving v Virginia with a case called Perez v Sharp. We also won the first school desegregation cases in the country, which set the precedent for Brown v Board. In fact the first civil rights cases Earl Warren ruled on were cases involving Mexican-Americans in California.”

“hen Thurgood Marshall and his team of Black Civil Rights lawyers were preparing to launch their assault on de jure school segregation Menedez vs Westminster School District was ONE of several key civil rights cases which Marshall studied or cited as precedents for the Brown vs Topeka landmark case; the late Willie Velasquez & Jose Angel Gutierrez met and consulted with Stokely Carmichael & H. “Rap” Brown of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) as Velasquez & Gutierrez prepared to launch the Mexican-American American Youth Organization (MAYO); the NAACP Legal Defense & Education Fund were instrumental in the founding of the Mexican American Legal Defense & Education Fund (MALDEF) and the Puerto Rican Legal Defense &Education Fund (PRDLEF) – MALDEF & PRDLEF are powerful organizations who are allied with the LDF ; the Black Panther Party directly supported the founding of both Young Lords Organization (YLO) and the Young Lords Party (YLP) ; Latinx activists have joined Black Lives Matter activists in demonstrations and political organizing efforts – in turn Black Lives Matter activists have reached out in meaningful ways to support Latinx families in Vallejo and Phoenix who have lost their sons to police violence.; the previous items are historical and contemporary facts/examples of collaboration ; it is true that the Black Civil Rights Movements existed in parallel with Mexican-American and Puerto Rican Civil Rights Movements – sometimes they even worked in collaboration.”

please again stop being racists, it is unhealthy and bad for the usa. also the light bult had many inventions and evolved with humanity through many years you can’t just pinpoint it to one race.

You are really trying to portray yourself as gods gift for what other poeple have done huh? Learn to read then read this article.

You just want to believe that you are white and not give the black/ African American people no credit. Your struggles don’t hold a candle to the struggles we black people lost and won here in this country and around the world heffa. You and your kind come over here with your mis-guided idealism, trying to assimilate with people who are only using you for votes and who find you gullible and beneath them. Keep drinking the koolaid of stupidity if all I care!

looks like you drank all that kool-aid bud

What we need is Latino unity and stop relying on white politics. I no longer can support a group of people that consistently show violent aggression towards our Raza! Where is the coverage or support for our street vendors that are being physically attacked by young black idiots! Don’t bring this nonsense about Latinos riding black waves! We work hard for our things and earned our place in this country through labor and sacrifice. Talk to your young blacks males that young sisters to stop with the aggression towards or Latino immigrants. They are gonna lose support from all sides and wake up this sleeping giant LA RAZA.

I agree with you. I’m a middle aged woman that grew up in a black neighborhood and remembered being bullied and attacked by blacks and the irony is that my father is a black latino but I look more racially ambiguous because my mom is fair skin but both latino parents. However, I was called all types of racist names referring to my ethnicity. I very much love the black community but the black community doesn’t have much love for latinos in general. And sorry but it’s mostly black women that carry this internal hate towards latinos n latinas even more and I have no idea why. So I can definitely empathize with your comment Jesus Barrera. Just the same way black people raise their voices for injustice in their communities, we need to do the same because we are being discriminated and mistreated by both white people and black people. We need to stop riding on the coats of blacks and whites and create our own lane. We have own resources and dont need crumbs from either side. Yes we need unity amongst all groups but we also have to create our own paths of opportunities for the future of our latin communities that are being shadowed by everyone else & leaving us behind as usual. Latinos must unite and form our own organizations and political groups to fight for our rights. This world isn’t just for blacks and whites. WE EXIST TOO!!!!

Black lives matter until they shoot each other civil rights for the uncivilized why do we believe they lies soaked in indigenous and asian blood fuck a black ameri thug they have no love not for themselves not for each other yet you wants us to see them as brothers fuck that not even my raza is unified I won’t participate in minority suicide just to keep the black mans ego alive while they brain and soul is petrified

Latinos don’t owe blacks a thing! Your twisted and and use twisted words and your OPINIONS are wrong and you should rethink your words before you open you mouth.

Do you have this translated into Spanish? I work at a high school and would LOVE to share this with the parents. If not, could I just translate it myself for this use?

Thanks!

We do not, sorry!

Here it is now! https://www.latinorebels.com//2020/06/04/latinosdeben/

Could you translate to Spanish so we can share with our communities?

https://www.latinorebels.com//2020/06/04/latinosdeben/

Silvia, more information for you….

1. The first school to be desegregated was in Colorado in the case of Maestas vs. George H. Shone, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maestas_vs._George_H._Shone , Francisco was MEXICAN!.

2. The second school to be desegregated was in California in the case of Roberto Alvarez vs. the Board of Trustees of the Lemon Grove School District, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lemon_Grove_Incident , Roberto was MEXICAN!.

3. The first state to be desegregated was California in the of case Mendez v. Westminster, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mendez_v._Westminster . Gonzalo Mendez was MEXICAN.

4. The second state to be desegregated was Texas in the case of Delgado V. Bastrop , https://tshaonline.org/handbook/online/articles/jrd01 . Minerva Delgado was MEXICAN.

5. In the case of Hernandez v. Texas, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hernandez_v._Texas , it was determined that “Mexican Americans and all other nationality groups in the United States have equal protection under the 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution”. Mexicans did not have the same rights as Blacks and White.

As a Latino, I empathize with the black community, as we face the same issues in different languages at times.

At 14, I got 2 ribs cracked and my arm broken by 4 police officers with their batons, while I attended a punch and cookies party.

However, regarding your headline, let’s go over facts.

Latinos have been in the U.S. longer than anglo and black Americans.

55% of Mexico was ROBBED, 1836 Texas, the rest 1848, Florida 1819, Puerto Rico, Guam, Philippines from Spain 1898, 1903 Panama from Colombia for the canal etc, all with the pretext of manifest destinty.

Latinos have served in every single war since the inception of the U.S.

There were Sanchez’s on both sides of the civil war.

We have majorly paid our dues.

This country owes us.

Well stated!! Our hardships of being Latino or Latina is on going, as presently demonstrated. As a present demonstration of individuals, Latinos, being caged like animals and treated like animals. No one else is going to pick our produce or work in the farms, and it is done with Pride. We even hustle on corners selling flowers or oranges, etc. We make U.S. great and keep the economy going.

Do you recognize black Latinos or do you only play the race card to benefit yourself

You’ve got it Alex,but that’s not taught in high school and even us never mention it to our children or grandchildren! I spent 28 years in the military and always let it be known I was Puertorican, wwweeepppaaa!

????????

Thank you for setting the record straight for the idiots who believe this poorly-researched and exceedingly insulting article. What a joke.

This article was written by someone that did very little research.

Pretty thoughtful but is without an Indigenous policial analysis. Without that discussion we have nothing. I also see that the writer worked for Liz Warren. I’m Native and live in MA. Too many people advised Warren to lay off the claims of a Cherokee identity and focus on the issues, but she couldn’t. It simply didn’t land. Even though she has done some work with the tribes here, she also recently missed the mark by not sponsoring a bill in this session to reaffirm Mashpee Wampanoag reservation land. We gave up on inviting her to engage with our community—shortly after she said that she’d back something under the condition of an entire group agreeing to something. Typically white political crap.

I understand some parts of what is being said but what I don’t understand is our Black men are killing each other every day just check the news for the last six months and none of us (Blacks) has rioted or marched not one time saying Black Lives Matter stop killing each other but just as soon as a Police officer kills one of us the rioting marching and looting starts. Don’t misunderstand me it upsets me too it could have been one of my sons, it’s not right us as Black people are human and have rights just like white people. But when are we going to stop killing each other. When are we going to march for us as a Black race should stand together and spare each other lives. Are we saying white man stop killing Blacks but it’s ok for us to kill each other. The riots that has happened just check most of the businesses that were destroyed were Black businesses not white. Stop for a moment and think about that. Blacks stop killing Blacks and to the Police we are Tired but we will handle it Legally.

It’s obvious you’re not a black person saying this.

Why should we feel the struggle long before our parents got here? What do you mean?! We are all minorities! Perhaps you should clarify if you are speaking for specifically about Central American Latinos or Mexicans? Overall all Latinos are minorities. They all get treated as if they were Mexicans or they are seen as minorities (different). Americans are taught lies about this lands history. And Mexicans….specifically Mexicans are from this land originally and feel the struggle everyday. The discrimination against Mexicans is real and it has been happening ever since childhood because the adult white folks feel Mexicans are from a different since they speak Spanish, and treat Mexicans as if they were from a different country. We are NOT white (100% white Caucasian) so we don’t have white privilege, we are people of color and feel racism all the time by being called names even by the president. Before anyone got here, our ancestors were raped. Remember California was Mexico? Even now Mexico is called Baja California (Lower California). Spain came and riddled with disease Native Americans died, those who lived were allowed to stay even after Spain started taking over the land. Eventually, cities they build got larger, one of them later became known as Los Angeles. Mexicans natives started realizing it, these people were taking over the land, they originally came to teach us their ideology. It wasn’t just Spain because later French came.

However after the Mexican war (people who were Spaniard & Native American, or Afro Latinos) they lost the land. That’s why Mexicans are Native Americans & multiracial since rape occurred, Mexicans have a percentage of Spain. But Mexicans are originally from this land. Some Mexicans may have African because the natives got with Africans who flee to Mexico to get away from slavery. The white People promised the Mexican natives to give them rights, but on the census they at one point had down Mexicans to be able to treat Mexicans differently. Supposedly, they promised to treat them as equals since they took over the land. Really strip Mexicans of their rights, but then Mexicans realized it and we’re afraid to claim Mexican due to racism and discrimination. So, after fighting to remove that from the census, as back then they preferred to be hiding to avoid any kind of hate. Then the non-white Caucasian was added. Today Mexicans & Latinos want to be recognized by the census and got upset about not being able to choose something other than non-white Caucasian because we are 100% non-white Caucasian and we are multiracial. We were always with black people because that’s how Mexicans (Afro-Mexicans, Spanish-Mexicans together was one=Mexicans In general) fought against the 100% Spaniards to take our land and be free. Regain our independence. Hint: Vincente Guerrero

Recall eventually Columbus (who isn’t even England) came, but later had issues with Spain & Gold was discovered… he came back with more people etc. England, Danish, Italian, people started coming, mostly Dutch. England people were the worse as they raped our people and murdered everyone. People were ruthless.. Then what is now known as United States. Everyone, but natives & their descendants are immigrants. Mexicans were promised to stay here just like other native Americans because Mexicans are Native Americans. They are a tribe if you will, but are multiracial.

So shall we stand with black people, is that really a question we must ask ourselves? The answer is yes, we have before and are again. But we are from this land and white folks later came and raped/killed our people. Now they claim that we are the immigrants? ? We feel the same pain,

It happened to us. Remember that we were kept because danish and other Foreigners who came to the land did not know how to farm, they sucked at it & they try to have Dutch do it, but they were no good. So, natives were out to work as slaves as many as 500 million. You can imagine all tribes. There would be no America without the native Americans who knew how to work & farm. Finally, it became illegal to have Native American slaves. Also, Europeans had no idea what to do, they eventually brought more slaves from Africa. At one point they brought Irish people who actually were somewhat good at farming, so they brought more of them. Overall, America is full of foreigners. We know now, we need Mexicans because in reality Mexicans are the only ones still til this day working in the fields.

Honestly, if racist people knew our true history they wouldn’t be racist, they will realize that Christopher Columbus Isn’t even white (as in German). White folks back then didn’t even consider Italians white, because they aren’t, they are Italian from a country called Italy. England is white from England. Italians and Irish people were treated as immigrants in history because they we’re immigrants even by the the white people (England people) who are immigrants themselves. Why? Cause Irish were brought here by them after they showed up. America was advertise as land of the free, for people who want to have freedom of religion and speech. Women from Dutch were promised housing, clothing and perks for them to come here (since men wanted women & they originally taught they would be good farmers). Instead Dutch women hated farming and were great baker plus teachers. Eventually, England made these Dutch people forget their culture & tried to abolish it. England people started making people only have their religion & making them speak English, not their foreign language. So today all those foreigners forgot their native language, such as Italians who are now born here today. Now everyone demands that everyone should speak English. Sadly, everyone forgot their mother tongue & true culture. It’s important to know your countries culture because that’s what makes us America, diverse.

Mexicans were natives before anyone else came, that’s why México is now known as Baja California (lower California). When you say Latinos that’s too broad, you must be referring to Central American. Because Mexicans are Native Americans who were killed by Spaniard diseases & mixed after they came. Prior to anyone from England or black People. Mexicans and blacks are allies,

why? There was a time when black slaves escaped to Mexico to seek freedom. Mexicans were promised to have equal rights, but treated like immigrants, so their was a Mexican revolutionary war. The list goes on for the fight of our land that originally belonged to the Mexican tribe who never got treated fairly or given any land, til this day US don’t want to recognize us, you know why? Because they are scared. Mexicans are the largest tribe, the Mexican tribe. We stand with Black people because we were slaves too! Blacks fled to Mexico for freedom, we joined forces and we are Mexicans. We are of mixed of races, but primarily our blood is of Native American with a percentage of European amongst other races, because the reality is we are multrace or biracial, even Afro-Mexican ;). Yep! Let’s move forward and stop dividing, because we are fighting for the same thing, equality.

Who told you that you are Mexican? Biology and true history are our friends.

All people on this earth come from BLACK, period.

Why should we feel the struggle long before our parents got here? What do you mean?! We are all minorities! Perhaps you should clarify if you are speaking for specifically about Central American Latinos or Mexicans? Overall all Latinos are minorities. They all get treated as if they were Mexicans or they are seen as minorities (different). Americans are taught lies about this lands history. And Mexicans….specifically Mexicans are from this land originally and feel the struggle everyday. The discrimination against Mexicans is real and it has been happening ever since childhood because the adult white folks feel Mexicans are from different since they speak Spanish, and treat Mexicans as if they were from a different country.

We are NOT white (100% white Caucasian) so we don’t have white privilege, we are people of color and feel racism all the time by being called names even by the president. Before anyone got here, our ancestors were raped. Remember California was Mexico? Even now Mexico is called Baja California (Lower California). Spain came and riddled with disease Native Americans died, those who lived were allowed to stay even after Spain started taking over the land. Eventually, cities they build got larger, one of them later became known as Los Angeles. Mexicans natives started realizing it, these people were taking over the land, they originally came to teach us their ideology. It wasn’t just Spain because later French came.

However after the Mexican war (people who were Spaniard with possibly French & Native American, or Afro Latinos) they lost the land. That’s why Mexicans are Native Americans & multiracial since rape occurred, Mexicans have a percentage of Spain. But Mexicans are originally from this land. Some Mexicans may have African because the natives got with Africans who flee to Mexico to get away from slavery.

The white People promised the Mexican natives to give them rights, but on the census they at one point had down Mexicans to be able to treat Mexicans differently. Supposedly, they promised to treat them as equals since they took over the land. Really strip Mexicans of their rights, but then Mexicans realized it and we’re afraid to claim Mexican due to racism and discrimination. So, after fighting to remove that from the census, as back then they preferred to be hiding to avoid any kind of hate. Then the non-white Caucasian was added. Today Mexicans & Latinos want to be recognized by the census and got upset about not being able to choose something other than non-white Caucasian because we are NOT 100% non-white Caucasian and we are multiracial. We were always with black people because that’s why Mexicans (Afro-Mexicans, Spanish-Mexicans together was one=Mexicans In general) fought against the 100% Spaniards to take our land and be free. Regain our independence. Hint: Vincente Guerrero

Recall eventually Columbus (who isn’t even England) came, but later had issues with Spain & Gold was discovered… he came back with more people etc. England, Danish, Italian, people started coming, mostly Dutch. A lot

of England people which were at that time the worse as they raped our people and murdered everyone. People were ruthless.. Then what is now known as United States. Everyone, but natives & their descendants are immigrants. Mexicans were promised to stay here just like other native Americans because Mexicans are Native Americans. They are a tribe if you will, but are multiracial. However, that was all forgotten in history and now Mexicans til this day are seen as foreigners by the true immigrants (England, Irish, etc)

So shall we stand with black people, is that really a question we must ask ourselves?

The answer is yes, we have before and are again. But we are from this land and white folks later came and raped/killed our people. Now they claim that we are the immigrants? ? We feel the same pain,

It happened to us. Remember that we were kept because danish and other Foreigners who came to the land did not know how to farm, they sucked at it & they try to have Dutch do it, but they were no good. So, natives were out to work as slaves as many as 500 million. You can imagine all tribes. There would be no America without the native Americans who knew how to work & farm. Finally, it became illegal to have Native American slaves. Also, Europeans had no idea what to do, they eventually brought more slaves from Africa. At one point they brought Irish people who actually were somewhat good at farming, so they brought more of them. Overall, America is full of foreigners. We know now, we need Mexicans because in reality Mexicans are the only ones still til this day working in the fields.

Honestly, if racist people knew our true history they wouldn’t be racist, they will realize that Christopher Columbus Isn’t even white (as in German). White folks back then didn’t even consider Italians white, because they aren’t, they are Italian from a country called Italy. England is white from England. Italians and Irish people were treated as immigrants in history because they we’re immigrants even by the the white people (England people) who are immigrants themselves. Why? Cause Irish were brought here by them after they showed up. America was advertise as land of the free, for people who want to have freedom of religion and speech. Women from Dutch were promised housing, clothing and perks for them to come here (since men wanted women & they originally taught they would be good farmers). Instead Dutch women hated farming and were great baker plus teachers. Eventually, England made these Dutch people forget their culture & tried to abolish it. England people started making people only have their religion & making them speak English, not their foreign language. So today all those foreigners forgot their native language, such as Italians who are now born here today. Now everyone demands that everyone should speak English. Sadly, everyone forgot their mother tongue & true culture. It’s important to know your countries culture because that’s what makes us America, diverse.

I meant Mexicans are NOT 100% Caucasian, we are multiracial.

I agree with what you are Trying to Say…just not sure if you are Communicating it Well enough to Generalize about the Latino Community…remember our Children are STILL being put in Cages! Latinos ARE participating…we are right now focused on the Riots; but OUR Children and People are Also Struggling to Belong…at home where there are little to now resources depending upon the family God decided to which you would be Born…and abroad…where they travel too…in search for work and a life without fear of persecution, rape, murder…We totally understand the intent of #NoJusticeNoPeace and #BlackLivesMatter. What can be said about #KidsInCages?

This is not even .01% of the Great American Conversation going on right now!

I almost want to say…the Audacity of this author to suggest that Latinos are not Engaged!

Not All; but Most Latinos…trying not to generalize beyond truth…just like every other Ethnicity…#WeAREWithYou

And to say otherwise is OFFENSIVE!

Separated/Pulled from their families?! We Understand how an Entire Ethnicity can be Generalized!

Not Everyone Is Good/Not Everyone is Bad! God gave us #FreeWill !

What do We WILL?

#GreatestRuleLOVE

An opinion. Not a fact. Offensive and dismissive.

Thank you. The author is quite clearly an imbecile.

[…] Latinos Owe Black Americans Everything (OPINION) […]

[…] Original English version here. […]

Great article! I know you’re going to get some flack from Tejanos (because I am one) about the whole “we didn’t cross the border” angle, and that is true. HOWEVER, as original Mexicans, you are correct: we also inherited the highly striated society built on racial lines that the Spaniards began, and for many, it was not until the Anglo-Americans subjugated us to 2nd class status (after Texas left Mexico) that we truly began to understand the problem with white supremacy and racism. Basically, we got taken. Unfortunately, MOST Tejanos don’t realize this because Texas history is taught (or was in my day) as thought white makes right, Anglos befriended and cooperated with both natives and Tejanos, and no better blessing could have ever beset Texas than rejecting Mexico and ultimately joining the United States. No mention of the desire to expand slavery westward, to rob Tejano families of their land and therefore wealth, or anything else that accurately depicts how Texas came to be. Given ALLLL that, I absolutely agree with your assertion, because for at least as long as Texas has been American. The topic of natives as slaves to the Spaniards and French ON THIS SAME LAND must also receive attention in these discussions, but I recognize that in itself merits its own full analysis and presentation. I would love to see more long-term learning between the Latino and African American communities about our shared historic struggles, even if the timelines are phase-shifted 100+ years or so. With the Spanish destroying or looting EVERYTHING that mattered to native peoples, it’s no wonder we are still in the dark.

Black lives matter and the protesting in America isn’t a message limited to the states. So many responses here try to devalue the protest claiming that Latinos get treated the same way as Black people in the US. But think about how black people get treated in your home country? Think about how little positive representation Black people have people have among Latinos. In this here united states of america, non black minorities have black people to thank for the many rights and freedoms that you have, in most cases, above and beyond natural born black Americans. Your desire to deny this point is showing your commitment to upholding white supremacy.

I am a Mexican-born, US-raised, 42 year old individual, whose upbringing took place in the streets of Compton, California during the early “Crack” years of the ’80s. I remember walking back home from Martin Luther King Jr. Elementary and being terrified, to the point of occassionaly wetting my school pants, of being beat up and robbed by the bigger and scary looking dark black kids. I did not know why they did not like me, or why they wanted to hurt me. I initially thought they where my friends…we were classmates, after all right? Sometimes they would catch me and take my quarter my dad had given me, sometimes I would be lucky enough and reach my front door before their capture. I also recall being terrified one morning because I was wearing what seemed to be the wrong color shoe laces, as a fellow classmate pointed out to me. Although not without making it clear that if certain black kids saw me wearing those I was going to be jumped. I ran home and ran back to school as fast as my lungs would permit. I was late. As I opened my classroom door and stepped in the classroom, I will forever remember the laughs and fingerpointing that I received that morning. Mexicans were a minority throughout my school years. I only ever saw two white kids in my school. They were twins and where the dirtiest and smelliest kids in the entire school. They also seemed the poorest. Those where the white kids I knew. The majority were black kids. And I was terrified. Nevertheless, year after year, we where bombarded every February with tons of Black History Month education. Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad, Marcus Garvey, George Washington Carver, W.E.B. Dubois, Rosa Parks, Marian Anderson, Jesse Owens, Willie Mays, Malcolm X, Nelson Mandela, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Diana Ross, Jackie Robinson, Thurgood Marshal, Rev.Jesse Jackson, and the list goes on…I was programmed with more black history than most black kids were. To this day, if you hear me speaking over a telephone call, you would swear I was Black! Mexicans from other neighboring cities would scold me for using the “N” word. I couldn’t help it. I was raised in a predominantly black community. It was inevitable that somehow I felt in a sense as if I was black as well. I still feel tremendous sadness whenever I ponder on the injustices that the black people’s have endured. I can’t help but feel the pain as my own. I fight with the hidden internal guilt of not understanding my own people’s struggle on a daily basis. I know very little of my Mexican historical heroes as well as oppressors. With time I have learned to accept this duality. Feeling embraced and attached to both cultures.My younger sister married an African American and they have gifted me with two beautiful Mexican-African-American nephews. I can look you in the eyes and assure you that I do not owe everything to black america. I owe not everything to brown america. I owe everything to the upbringing my parents gave me. To the daily, faithful, painful, struggle that they both underwent in order to attempt to provide their son with a better education and a brighter future. Leaving their hometown in Michoacan while still being teens and also carrying with a 3 year old son on an unknown journey towards a never before seen country was surely not an easy endeavor. I am grateful they made it. I owe everything to their struggle and there drive to fulfill their dreams.

Your lineage wouldn’t have a country to come to (LITERALLY) if not for black ppl clearing and working the land. It’s just a fact. Also, white jealousy of black equity creating prowess moved them to prop up non-Black groups (like latinos) incessantly to marginalize and dismiss our ancestral labors. You’re a part of the problem when you join them in denying what we’re owed (monetarily and tacitly).

If you want something so bad get a job

Two things.: Mexican-American Civil Rights movement and The Black Civil Rights movement were parallel movements which rarely intersected – look at Texas/Tejas. Mendez vs Westminster is but one of the legal precedents that T. Marshall cited /studied for the Landmark Brown Vs Topeka . Brown was just larger in scope and impact regarding race. However San Antonio vs San Antonio independent School District, Lau vs San Francisco Unified , Tyler vs Poe , Aspira vs Board of Education, etc. are all important cases which impacted more children than just the specifc non-Black children of color that the advocates were fighting for. All struggles are dynamic and important. As you know, Sean Monterrosa was,Latino, was shot in Vallejo, Ca unarmed on his knees ,and with his hands raised above his waist. Finally any Black person who claims that Black community activists in cities throughout America have not pivoted to attempt to solve black deaths caused by communal violence is , well,not woke . A lucha continua!

You literally cannot be a Brown or Black person in solidarity with African Americans and call yourself “Latino”.

Latinos aka Spanish and Portuguese literally were the enslavers who created a system of white power throughout the Americas.

Of course people will say “Latino” is more inclusive (I agree), in a National sense. It is inclusive of all settler states. It is inclusive of all geographies going south.

But is it racially inclusive? Not at all. If it was people would not need terms like Afro-Latino or Indigena to describe themselves.

Which is why DeLoera is able to completely ignore “Latin America’s” complex history of slavery, racism and white supremacy and talk about “Latinos” as if they are just white immigrants acting as “Allies”.

A few interesting points…. but having started from a false premise…that reinforces stereotypes of immigration status… and ignores mass enslavement of Blacks and Natives by “Latinos” it’s hard to talk seriously.

I’d rather see the “opinion” that starts from the perspective that many “Latinos” are Black are Indigenous and we are not just in it to be “allies” but rather we have a shared history of oppression that needs to be acknowledged, recognized and respected by Blacks and Indigenous on both sides of the Anglo/Iberian language divide.

You’re a fucking moron Latinos is a language not a race and Spanish and Portugese have nothing to do with Mestizos at all that’s like Iraqis blaming black slaves for Military attacks talk about non sequitur.

Stop racism by learning to remove all racial labels from both discrimination and privilege, advantages and assistance for wealth that all individuals do not have. Remove all minority labels, privileges and benefits the same way you remove all majority labels, privileges and benefits from race, gender, religion and only compete as individuals. As long as you allow people to self-associate with a race, gender or religion there will always be racism and always be people trying to twist the logic to allow only their own racism to be allowed to be a racist and claim their own racist, gender or religious label to be “politically correct”. There is no equality in that form of racism and never will be until all labels are removed and we are just “individuals”.

Educate yourself about institutional racism exercised by all individuals of ANY race with institutional hiring and firing power, or political power over other races, genders and religions and how it differs from individual racism by members of ANY race exercising personal intolerance, prejudice, discriminatory behavior, superiority, and hatred based individual racism at : https://areomagazine.com/2017/06/16/racism-does-not-equal-prejudice-power/

You will find an excellent analysis on the tactics of institutional power used to harm people of all races, every manager who has hiring power and hires only their own race is guilty of individual racism and institutional racism. Honestly the only way to stop racism is to listen to my two hero’s Morgan Freeman and Candice Owens…stop labeling people with a racial label, stop identifying with a race, remove the B in black lives matter to just Lives matter, and change check your “white” privilege, to all races to just check their own institutional privilege position in society to oppress another race, gender or religion, or prevent an individual from having a job and electing people only of your own race, gender or religion into positions of power. The US constitution has the answer if you listen… all people are individuals with only a very small and limited number with institutional power under the common law to be an institutional racist exercising the R=P+P privilege to oppress other races when members of any race hold that institutional power to oppress members of other races, genders and religions. This power is reduced only when the existing concept of racial labeling is eliminated in all its forms and laws regarding racial identity group self-association and institutional racial power are held in check by racial labeling laws held equally to all equally without prejudice or discrimination or privileged affirmative action, section 8, or privileged admission to school or job based on race, gender or religion preferences, privileges and institutional power based on the race of the person holding hiring power or admissions power being an institutional racist by always associating with a race and identity group and oppressing all but the members of their own race. Stop racism by removing all identity group labels and claim only equality as an individual.

[…] must be thankful not to the white supremacist state but to the oppressed people who came before us, most of all to the Black community, which fought for so many of the rights and freedoms we now take for granted as “American,” and […]

[…] De Loera-Brust, Latino Rebels: Latinos Owe Black Americans Everything (May […]

[…] De Loera-Brust, Latino Rebels: Latinos Owe Black Americans Everything (May […]

M..is correct!! We are trying to decided what to do right now by what happened in 1600s.. just based on the color of skin? I was raised in an all black neighborhood and was jumped and harassed daily.. I got the hell out,blacks are probably the most racist people on this planet..I don’t judge by skin color I judge by what curtain people-Do actions.. My trust for black people took a hit because all of the violence,crime and total disrespect for other races.. if I say that some how I’m a racist ?? The system is set up to try and have a civilized society,for you to live a life you create- it’s not set up by colors.. every color has privileges and faults..We all are great and we all suck.. if you debunk systematic racism it’s really easy..activists and race baiters spin the numbers to try and make them match.. for an example- 0.08 percent of blacks are killed by police 99.0.2 are not.. To react with looting,burning blacks neighborhoods,stores is crazy..more black men were killed during the riots than cops.. the media and politicians are a huge problem with this. White boys with all that privilege are the most killed by police by far.. 1800 since trump took office and not one thrown on the news..black guys being killed is a better story.. that’s when la Rosa,BLM and all the activist that spew anti white hate and stir the pot..it’s a game,they get money and power and the people get nothing..BLM receiveD 40 million For George Floyd’s death which had 0 evidence of being racist sep for the cops skin color,but thousands are in the street screaming racism.. activists focus on half truths and lies of events that only show the bad side.. could you imagine only hearing one side of a story in court then decide if a person is guilty or not? This is going on in every country sep Africa..doesn’t that seem kind planned?? People demand respect,but you have to earn respect,in all races communities there is work to be done,but blacks need to take responsibilities for their action,take on the gang issues if they plan on living the American dream..until then-nothing will help.. in the cities that look the other way on black crime are democrat states,the same states that try and welcome Mexicans to..they need people who they can control. They ask for tons of money for schools and social programs every year,throw money at issues and nothing changes,it just gets worse.

I’ll accept that if all the black Americans would accept they owe everything to the 50,000 + white soldiers who lost their lives fighting for the emancipation of the slaves. As simple as that.

The North wouldn’t have WON if not for BLACK SOLDIERS being allowed to fight on their side (do the research). And white DOUCHEBAG Abraham Lincoln paid slave masters in 1862 for Black ppl escaping bondage. The Civil War is just a horrible, HORRIBLE starting point for anybody non-Black to start propping up white people. Try again….I’ll wait…

[…] “Too often we have brought with us to the United States the anti-Black prejudice that [is] prevalent …,” Antonio De Loera-Brust wrote May 30 for Latino Rebels. […]

This is one of the stupidest, most counterproductive posts I have ever seen. We don’t owe anything to anyone. We’ve worked hard as hell to get the little we have. The black community has not done a thing for us. Not a thing! They haven’t “taught us” anything.

The black community has always worked for the black community. The author is insulting the history of the work of Hispanics in the US. Remember, Latinos didn’t beging with people from the caribbean or from central and south America.

Worthless post that marginalizes the Latino struggle for civil rights. Is the author of this article even Latino? The author also ignores the racism and discrimination that Latinos have faced on a large scale from Black-Americans. Lots of black-Americans have supported the anti-immigration cause and called for boycotts of the Dominican Republic due to racial reasons.

This article is definitely an opinion alright and the wrong one for sure. To say we owe Black people anything is a form of malinchismo. I could either write a whole paragraph on how wrong you are or I can let you know this article is a joke and a spit in our face. I’d rather do just that and let you learn on your own.

It’s not a joke, ..it’s history. Read up.

Excellent piece and well said!

I agree.

This article is Black Supremacy at its worst… Us LATINOS DO NOT OWE BLACKS ANYTHING!!! HAS ANYONE HEARD OF HERNANDEZ VS. TEXAS IN 1954 (supreme court case)? No… DOES ANYONE KNOW WHO GUSTAVO C. GARCIA WAS? NO!!! Research it before writing racist garbage on the internet. That lawyer is the one that convinced justice judge Earl Warren to protect Latinos as an ethnicity for the first time (since we were consider White before 1954 under the U.S. census). That being said, Gustavo convinced the United States supreme courts to also protect us as an ethnicity under the Equal Rights Protection Clause of the 14th amendment. This allowed the Bill of Rights (the first 13 amendment to apply to us Latinos way before the Civil Rights Act of 1965). If anyone should be grateful that someone opened the door to the Civil Rights in the 1960s it should be Blacks that have forever swept all the rest of our history under the rug with their racist rhetoric all over the bias media. This article makes me sick on how twisted and untruthful people lie about my ethnicity. Also, this case allowed mixed juries since.

The Hernandez case wouldn’t have a 14th Amendment to umbrella under if not for Foundational Black America. Stop the bs.

Thank you. Well said. WE DO NOT OWE BLACKS SHIT!!! Latinos and Hispanics we need to stick together fight for our rights and we want our history to be taught in school as well.

Then go back to your country in Latin America and stay there. You ain’t dyin you multiplien. Multiply down there.

lmao is this even english?

Wow. I learned so much in the comments. I have native American friends who have told me the truth. Mexicans are in truth the original natives of this land. Period. Whites came, killed off whole tribes now they are returning under the name given to them. I am African American. I knew a couple of Mexican women and men in my time, and they were never racist towards me. They were loving and kind much like their ancestors, and I respected them deeply.However, am not dumb, and I know how racist non Black people can be towards us. That being said. It seems we are all being compartmentalized and organized by people who feel evil and hate is the only thing they need to stay “on top”. Givem a name, divide them by color, and kill them slowly. I for one plan to move back to West Africa where my ancestors were stolen to be used as free labor to build this country. I feel all Black people born in America should. That’s real reparations. God Bless the Mexican movement of progress and fortitude in this country. I know who you truly are.

Let’s get your article straight:” Latinos Owe Black Americans NOTHING”… other than thanks for trying to drag us down with your negative stereotypes. Instead, we rise up by becoming educated, hard-working taxpayers, and contributors to society. We reject your attempt to force co-mingling… for we never want to erase our own proud history and legacies!

Stop. Latinos were slave owners and slave catchers, and wouldn’t have born citizenship to leech off of if not for Foundational Black America. Latinos OWE BLACK PEOPLE THEIR VERY LIVES.

I agree 100% we don’t owe them nothing! Stop harassing our street vendors! Talk to your young black cowards that sucker punch old people! You want Latino support? Fix your own problems first, stop your senseless bullshit against our immigrant populations! We DONT OWE YOU NOTHING! My family and I worked hard for everything we own. Y’all should try it.

What exacty do we owe blacks? Tell your young black coward males to stop harassing and sucker punching our street vendors! Pass the word…Just for Latino Street Vendors! All Lives Matter

You need to stop and do better baby boy. A year late sure but I hope you made it through another year without the black on black crime that will put you in an early grave.

Imagine being this much of a cuck for blacks. I’m tired of Hispanics kissing black peoples ass and not vying for themselves. You’ll talk crap about another Hispanic group, but bend the knee to blacks. It’s absolutely pathetic. Blacks are hostile force that want to crush Latinos and control us both on every level including politically and sexually. Hispanics need to STOP supporting them.

Yep. We need to support ourselves. They will erase us if they could.

We dont bow down to nobody. With the way black americans try to block us from having political and economic power to their campaigns of cuktural erasure, we dont owe them anything else but a war to maintain a separate identity. Our 22% vs their 13% will equal a smack down they will never recover from if they don’t start respecting us. They just like whites are guests in our hempisphere.

So are the white Spaniards ….ones you bow down to and worship…Guest in this hemisphere

We dont worship anyone. Accusations of racism are a last ditch effort and sgn of your fear of our numbers and our power. Call us what you want. We out number you and will never follow you. We are running things now. Name calling won’t change the fact that Latinos are the big one on the block and very soon you will be forgotten.

Wow, I see a lot of denial of how the 14th amendment came along and it’s significance to the rights of all minorities and those trials mentioned. Also using the fact that Europeans stole Mexican land, to deny how you benefit from the black struggles is almost as lame as using your personal experiences to negate the benefits of the black civil rights movement on all minorities. This article doesn’t call Latinos lazy or anything bad. It simply states that the enslaved people (primarily from Africa) set the foundation for which minorities like Latinx benefit in present day America. The fact that anyone who benefits from the black civil rights movement would use black motivation to better “their own situation” as a negative is further proof of the ludicrous and unnecessary division between our communities. Remember this…. the ancestors of enslaved Africans do not have another home as all of our heritage was literally beaten from us and we had to stop our practices for our survival. We are always going to fight harder because this is it. And the Hippocrates that leave Latin run countrys (who also owned slaves) because of Latin on Latin crime and/or poverty have some nerve talking about black on black crime as an excuse to negate the benefits of the black Civil Rights Movements. Those Latinx should really take at look at their own people before passing judgment on a group of people who are here because of kidnapping, rape, and slavery of Europeans on Blacks. This article calls for respect and credit where it’s due and nothing more. It’s not anti-latinx, but here we go with that crabs in a bucket BS

1. God forbid Black people get credit for anything, right?

2. Latinx didn’t benefit from the 14th amendment?

3. We should solve/stop all crimes within a race before tackling racism… so Latinx people really good with that for themselves too?

4. Blacks aren’t the most vocal about injustice and we know which country we can go home to just like every other minority?

5. Black Americans are the “best” choice to discuss Latinx struggles because our struggles are identical and infact we can speak for everyone’s struggles because they are all the same?

How about a big fat NO to 1 – 5

These excuses some of you commenters are giving are proving the authors point. I wish you could realize that so we could move on to the real villain in our shared history instead of falling for the okie doke! Don’t confuse your personal experience with American history and stop bringing up European atrocities to negate the blood, sweat, and tears of allies because it’s ignorant using these sort of deflections from the real points of this article.

Yet blacks are commiting hate crimes almost at the same rate as whites yet their population isn’t even 20%.. guess who they attack? Mestizos and Asians.

im a black man from long beach, 34 years old and went to burnett elementary, dont know the name of it now since it been discovered that Burnett was a racist man. grew up with lots of latino boys in my neighborhood that i trusted more than the black boys tbh but thats besides the point. the point is community, and applying the golden rule. We should all stand up for each other, about maybe 6 years ago, maybe even longer. a 13 yr old boy showed me a video of a cartel thug beheading a woman with a knife for snitching. ON FACEBOOK. i dont even know how i can live with myself knowing this level of evil is spreading itself on the internet for kids. the boy was just already desensitized to it, how can this country be our neighbor and be in this level of shape? we fight wars that are none of our business but we cant take care of our own, and our neighbor? so blacks and latinx should always stick together. when you look at history, transatlantic slave trade was terrible. it just seem like throughout history the lighter races just believed they could enslave anything below the equator and its just shameful. i feel like we in america need to put our differences aside, call out all of our bad apples to get whatever help they need and not just jail them all, fix ourselves, help others, while calling out our government to find better ways to help our neighbors and US territories. Almost every day of this pandemic i think about how i wish i could be a part of some real change in Africa and track down your roots and everything with some ancestry, but even that, the rape of african women was moreso currency and cant even be tracked to an origin like others dna can. almost like are origin is now the rape of africa, whats made that worse in the generation is now people are even less sympathetic to that. the sugar farms slaves died a dogs death for a white mans sweetener. Latinx community will always have a neighbor in me. i may not know all the civil rights stories but do know the truth of fleeing corruption, and i do know that the struggles we suffer in a community we do together. And lastly i do empathize the similarities AND the differences between the struggles in our history brought to us not by own doing or our full knowledge. american govt makes all minorities fight for the same piece of pie, squeeze us all in the same communities to fight for the same resources. make our kids hate each other, then show our kind hating each other on tv (script still written and directed by a white man) reaffirms a false image to dislike and distrust.. i have no love for the media of the 90s or the 00s. those were the years we needed to cultivate each other but it got hijacked by rude comedy and jackassness, now mental health is a pandemic too. and OF COURSE its disproportioned against blacks and latinx again.

Yeah. I don’t owe any other community anything. Black Americans have a tendency to try to prove that they are dominant in the faces of other minority communities they sense are quiet, passive, and well-assimilated. Specifically Latinos who don’t bother anybody and keep to themselves. And heaven forbid you get loud and stand up to them.

This coming from somebody who used to cuck hard for the black community because I felt my light-skinned privilege was a detriment to their advancement as a people. Sorry, but I’m not bowing down to people who bully me. Leave your shaming politics for white people.

I agree with what you’re saying when it comes to black Americans and I wish it wasn’t like that 🙁 But they would call me a racist if I voice my opinion not knowing that my father is an Afro-Latino and that makes me half black myself but since my skin is light and my ethnicity is latin, I don’t have a right to speak on anything relating to black issues according to what I’ve blatantly been told to my face by black people but mainly black women. Same way that we latinos are chastised & patronize for our urban music our tropical music and called culture vultures. Black Americans act like they own the entire black race and that they are the only black people on the planet. They criticize white supremacy but they act the same way towards latinos. They make fun of our culture and our language and pretty much clown everything we do, but criticize biracial latinos like me for identifying as latinos instead of saying we’re black. Because if we dont identify with a color like they do, we get called names for denying our African heritage and that is soooo farrrrr from the truth. But on the same breath, I’ve been told to mind my business and stop speaking on black issues when I try to voice my opinion against injustices. I voice my opinion because I care and also because I also have African blood running through my veins whenever American blacks like it or not!! I just think its time we latinos start fighting for our rights instead of theres because I’m sick n tired of their issues always the ones being highlighted and we as usual are always left behind. We need our own lobby groups and our own political agendas bc we are not wanted on the white side or the black side. We latinos need to unite and uplift each other.

Yeah we don’t owe them shit (FACT)

Wonderful article! Even better are the commentators solidifying the author’s message. I love latino culture, Mexican culture particularly, yet I remain skeptical as so much of Latino culture thrives in anti-black ideologies and rhetoric.

“Mejorar la raza,” anyone?

Bullshit there is no anti blackness in Mestizo culture you’re wrong. There is clear racism in black culture they murder vendors that are raza target undocumented when they cash their checks and have targeted our elderly and murdered many.

At this moment in history it seems like both Blacks and Gays are trying to make everyone bow down to them. Listen, I will be your “Ally” but I will NOT allow you to simply replace the white man as the overseer, trying to tell me and other Latinos we “owe” you. I owe blacks and LGBTQ’s NOTHING. I worked for everything I have. My father worked for everything he had. His father and so on. Latinos have never had it easy. We fought for our own progress. No one paved the way or helped us. We owe no one.

First of all Latinos owe nothing to blacks because blacks don’t have anything but an illusion that is allowed for them in feel in control. I for one as a Latino don’t like to have to live in the ghettos that the general population of blacks live in. If that is consider a progress by the Author this is one thing the blacks can keep. Should I say more? just that encompasses all the so call progress the black community has so call accomplished. Civil rights what civil rights? When you are used as a pawn on the political game of the elites for their gain and you keep living in the crime infested ghetto where the black families suffer poverty and their children die in the streets at the hand of tugs and nothing is done by the authorities, what civil rights do you really gain? is all fake, Is that what the author think we Latinos owe the blacks and shall strive for to live on those conditions? Please give us a break open your eyes and see the truth. The Author must be in debt to the elites. Yes you sound political correct and may win an Pulitzer Prize for such an illustrious analysis but you also sound ignorant. By your name, Antonio De Loera-Brust you are not even Hispanic or at least you are not to proud of your Spanish heritage that you have to use your anglo last name so that you can stand out from the rest of us Mestizos. Wake up people and don’t let the misguided sellers of snake oil try to sale you the fantasy. We all are still in the plantation of the elites. the elites that play us one against each other to keep control and rob us of our assets to enrich themselves even more at the cost of our families and children future. No Antonio De Lorea-Brust you are wrong you may owe all that to the black community but not us Hispanics, Latinos or whatever they want to call us. We know who we are and what we want. We have drafted our own destiny since 1500 AD we fought off the French, Portuagues, Germans, Brits and US Army of our lands and for our freedom long before the American colonist brought the blacks to American continent. We don’t owe anyone anything but our ancestors and we will not allow little pathetic pretenders to draft our great future destiny. Good luck with your personal debt to the blacks and please don’t include us on your own psychosis.

Which book did you read ?? You should know that hispanics / latinos can be of any race so you must be targeting Black Americans i assume ? Also please edit your writings before submitting..your short essay.. it is full of grammatical errors.

We get it…you wrote an article. Stop acting like your some next level author in the likes of Fredrick Nietche. First off, I don’t hate people of any race. However we should all acknowledge that the government doesn’t give a shit about anyone, but corporate interests. Stop with this wishful thinking of reparations. Because from the Indians, Africans, Irish, and Scottish we were all slaves at one point. And yes indentured servants are slaves. I mean shit they’re child slaves in every third world country now. Why aren’t we standing up for them. Mr.author! Why aren’t you caring about what’s happening right now?

Slavery is evil, and none of that history should be justified. However modern day people creating a victimhood isn’t going to save them from the past. It will just make them develop a weak character. And no one! Not even bosses respect weak people. They’re black, mixed people, and native Americans that are establishing their own businesses. Because they put in the hard work! Not because they get on their knees and beg for money! No! Because they actually put in the hard work and was smart enough to handle their money! I’ve seen modern Americans. And my gosh almost every race and ethnicity act like a bunch of sensitive crybabies. Even though most of these crybabies of all ethnicities live in good neighborhoods.

Meanwhile poor Americans of any background live with pain and suffering. Because they live in trailers or ghetto ass towns. Yet some of these poor people are every background. So instead of reparations why don’t we help out the poor. Because then most low class Americans would get taxed! Which is why reparations or money for the poor will just be a concept. There still going to tax you. America thrives off of taxes! What makes you think you ain’t going to owe the irs back?