CHICAGO — The recent videotaped killing of George Floyd, a 45-year-old African American male, by police officers in Minneapolis has stirred a critical dialogue regarding a pervasive legacy of state sanctioned anti-Black violence and oppression. The outrage against Floyd’s death has been epic and comprehensive. It has sparked militant protests against police terror, racist criminalization, and mass incarceration in cities across the U.S. and beyond. This is not the first event as such in African American or African diasporic histories.

Those histories are, in fact, narratives of either radical demands for equal protections under de jure law or a radical commitment to abolishing any condition that imperils or harms Black life. Black protests, either in moments of insurgency or civil disobedience, always exceed and challenge formal politics. They do so by necessity. Formal politics, as a host of historians and political theorists have shown, can be described as the source of the very harm that Black protest movements aim to disrupt if not abolish. In this critical perspective, police brutality is not a problem or aberration but is symptomatic of how law enforcement in the U.S. was designed from the outset. Protests and social movements are thus the leitmotif or are a central trope in Black histories.

Building on the work of scholars such as W.E.B. Du Bois, C.L.R. James, and Cedric Robinson, Black freedom or abolitionist struggles also loot, remix, and make better use of western or European enlightenment thought and its commitments to universality than have any political movements overseen or led by white people. There is a far clearer articulation of and dedication to freedom or equality, for example, within the liberation movements of African America than there is within the American revolution against the British. Unlike the American or even the Texas revolutions, Black liberation struggles in the Americas were never tainted with the burden of oppression towards a racialized other. Black histories are thus freedom quests that begin with, are conceptualized, and are driven by the position or purview of the unfree. Freedom in the Black radical tradition was never imagined as a place but as a state of being or a process or a tactic to survive and move beyond harms imposed by white vigilantes, law enforcement agents, and sometimes also the U.S. military. Conversely, the legacy of Black freedom struggle has been looted by all Americans. America and the world have looted from the labor performed by Black freedom organizers and abolitionists, from the music and literature generated by Black thinkers, and from the historical examples of solidarity and communal kinship that characterize Black histories of protest. Nothing arguably represents the essence of democracy in America and beyond more than images, sounds, and the practice of Black revolution.

I wrote this article because Brown communities owe our solidarity to Black liberation struggles. Those struggles have helped open our eyes to how racism works within and through the criminal justice system. Those struggles help open a space and have created a language from which a militant defense of Brown lives against police terror at the border and in our cities has transpired. On a smaller scale, the struggle for Black Studies at the university where I currently work has opened up a space and has given momentum to the growth of fields such as Latinx Studies and Asian American Studies. My book, Black-Brown Solidarity: Racial Politics in the New Gulf South, furthermore, chronicles how a Brown man named Luis Torres was beaten and choked to death in 2002 and in a strikingly similar way that ended the life of George Floyd. Torres was the same age as Floyd, his violent encounter with police was also captured on videotape, and it transpired just miles away from the neighborhood in Houston, Texas where Floyd grew up. Torres’ Black neighbors and Black political organizations from across Houston were some of the first to voice a protest against Torres death and this was due, in large part, to the significance of African American history and a legacy of Black protest in the Houston area.

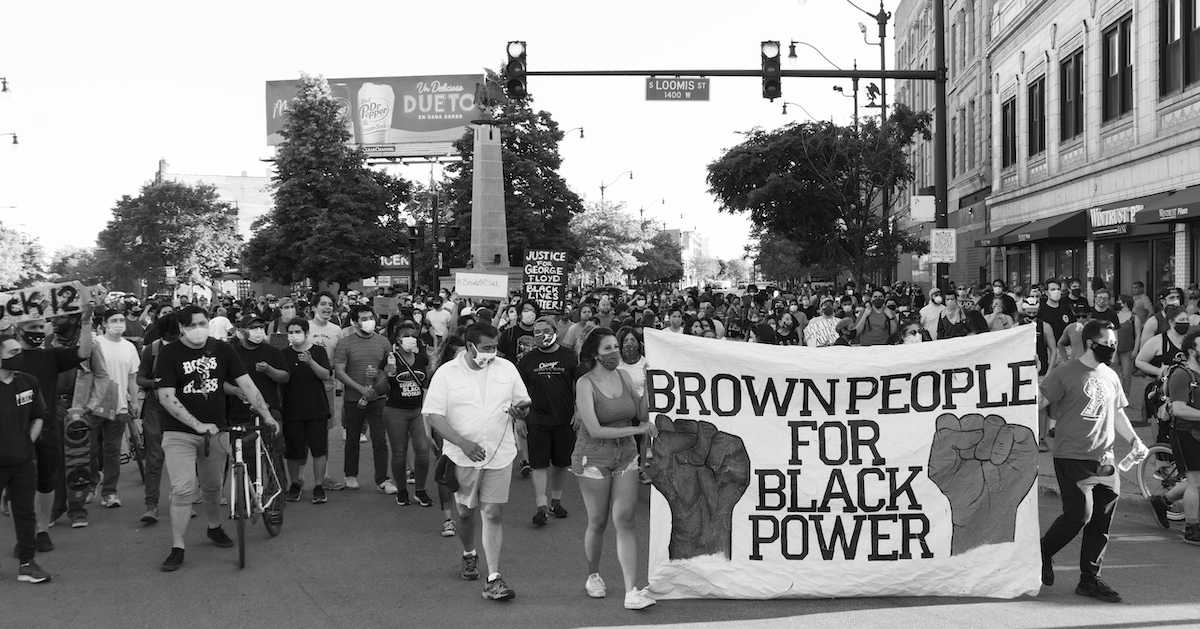

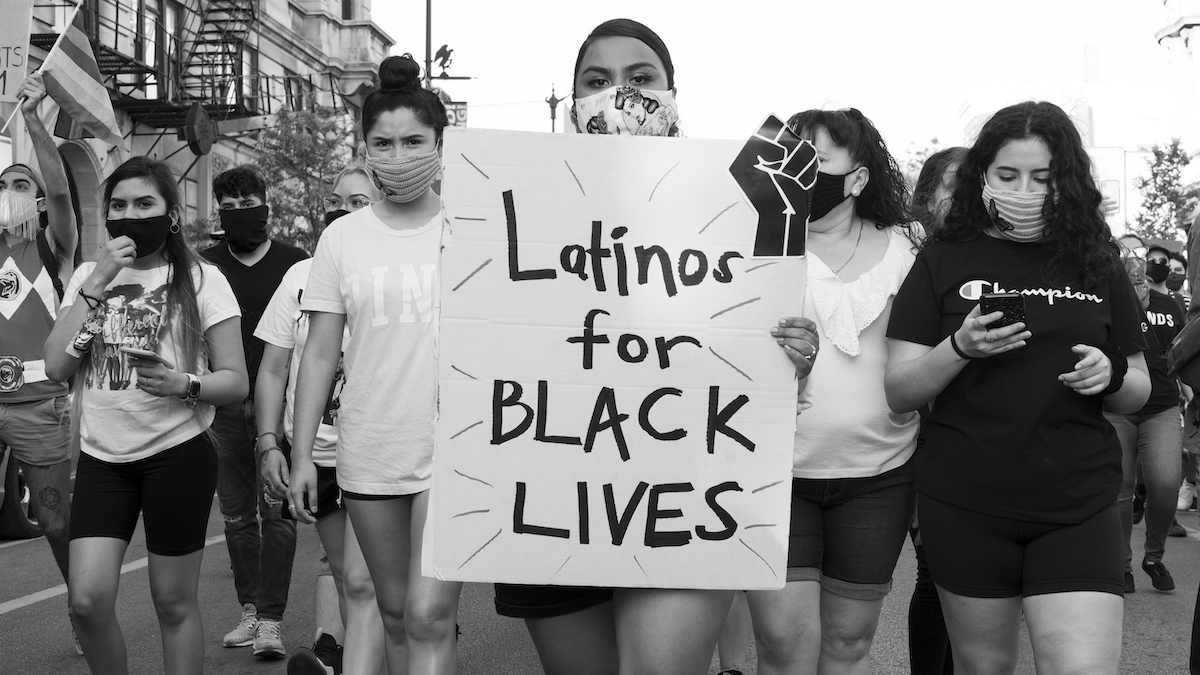

I write this article from Chicago amidst protests stirred by the Floyd case that my family has participated in. Brown responses to the protests stirred by the Floyd case have stirred a serious debate regarding the constitution and viability of Black-Brown solidarity in moments of uprising. In response to often destructive methods of protest, it was alleged that Brown street gangs in Chicago dedicated themselves to defending their varrios (Chicano slang for home-neighborhood, more commonly spelled as “barrio”) from damage. On the one hand, this can be seen as an example of Brown self-determination and mutual aid that corresponds with some of the definitive qualities that underlie Black revolutionary histories. On the other hand, it was also alleged that anti-Black discourse accompanied some of this Brown commitment to varrio defense. The latter is a problem worth inspecting and unsettling.

Details regarding the degree of this discourse or of Black-Brown tension and how it became visible have been debatable and not always clear. I am also wary of how such information, in the past, was often manufactured by state agents so as to create discord and disunity amidst moments of protest. What is not debatable is that the uprising stirred by the George Floyd case has not only exposed contradictions between and within groups. It has also created an opportunity for critical political education regarding the salience of anti-Black oppression to life and politics in the U.S. and the importance and pitfalls of solidarity. Moreover, the Floyd case has again helped to highlight the salience of hyper-carceralism and police terror as trademark characteristics of a post-industrial and neoliberal political economy that has proven to imperil Black and Brown life in particular.

The Floyd case has provided an impetus to critically scrutinize differences between and within groups as a mass movement to pushback against these draconian conditions has been mobilized. It also provides the impetus for conceptualizing police terror as related to the imperial footprint of the U.S. military in places like the Middle East, South Asia, and North Africa. The uptick in aggressive policing, in police brutality, and the expansion of prisons does not correspond with the increasing reach of the U.S. military across the global south by chance. These are all conditions that originate in the racial and settler colonial architecture of the U.S. nation state as it relates to Black, Brown, and indigenous peoples. It’s all connected and such connections are made amidst the masses of people who have taken to the streets in solidarity with Black Lives Matter and other Black liberation struggles.

It makes some sense for us to highlight how and why the appropriate connections are not made and especially if there are tangible examples of Brown communities practicing anti-Black racism during a moment when anti-Black racism is being challenged on an epic scale. Those critiques, however, can’t be all that we talk about when we assess either the failures or possibilities of Black-Brown solidarities. There’s a balance to be struck between (A) the critical work we must do in order to fortify social movements and address contradictions within and between groups and (B) the work to protect communities that already suffer from misrepresentation, violence, and criminalization. It’s important to be wary of how colonial authorities encourage and will incentivize a focus on intra-group and inter-group tensions in order to try to derail insurgent challenges to the status quo.

Black-Brown solidarity has always coincided with Black-Brown tensions in some of those same communities. I’d argue that there’s been much more solidarity than tension in Chicago. I personally have witnessed thousands of Brown Chicagoans, from the young to the elderly, marching in solidarity and doing essential work to defend and protect those who have been willing to engage in militant direct actions. Examples of what can be theorized as a Black-Brown solidarity across the Americas can be traced as far back as the 1700s when runaway slaves were offered refuge within indigenous communities, helping to form new maroon societies that imagined other possible worlds outside of the grips and violence of settler colonizers and slave drivers. In the 1800s in Texas, runaway slaves either joined indigenous groups or fled to Mexico where they were offered refuge from white Texican slave patrols. This legacy was carried forward for centuries and over subsequent political-economic conjunctures. It was quite apparent during the racial power movements of the 1960s and 1970s and in the profound solidarity between groups such as the Young Lords and Black Panthers in cities like Chicago or the Brown Berets and Black Panthers in Oakland and Los Angeles. Black-Brown solidarity also remains visible in the heroic and yet often overlooked activism and organizing that Black and Brown youth do every day in cities across the U.S.

They often do this work in the shadows and without any reward of recognition as has been the case in Chicago during the Floyd case. Their work is sincere, courageous, and compelling. Coalitions against police brutality almost always emerge from the organizing work and bravery of Black and Brown women who build coalitions with one another in defense of common home-spaces. None of this erases the significance of anti-Black thought or prejudice within Brown communities. None of it erases the significance of anti-Brown sentiments or xenophobia within Black communities in the U.S. But it does offer us a context that validates all of the work that has been done and that we can continue to learn and grow from in how we think about and practice solidarity. The title of this very article derives from the lyrics of the late Tupac Shakur (Tupac’s name itself reflects the Black-Brown solidarity of his parent’s generation and of the U.S. Third World Left) who often linked the fates of working-class Black and Brown communities in cities like Los Angeles. To this end and in the spirit of Tupac, the following represents five pillars that I propose as a base from which a stronger Black-Brown solidarity can be imagined if not furthered.

- Black-Brown is a common phrase for a reason. There is a reason why the term enters political discourse so commonly. This term refers to a conventional wisdom that two groups disproportionately experience the ill effects of aggressive policing, vigilante violence, and mass incarceration. The statistics speak for themselves. From lynching campaigns in the south and southwest of the early 20th century —to police brutality at the border and in our cities in the late 20th and early 21st centuries— and to the demography of county, state, and federal penal institutions; Black and Brown histories and fates are linkable or perhaps should be linked if we are indeed committed to a radical challenge to a racist status quo and a carceral state that imperils life on a grand scale here in the U.S. and beyond. The political discourse of the moment also demonstrates how right-wing populism (if not also white nationalism) is often inspired by elected officials creating and disseminating moral panics regarding Brown immigrants and Black criminals in particular. This is evident in slogans using the term “war” such as “war on crime” “war on gangs,” “war on drugs,” or “war on immigrants.” To thus describe oneself as a “law and order” politician in the U.S. carries with it or is informed by an implicit anti-Brown and anti-Black bias. “Dog-whistle” politics that appeal to American patriotism imperils Black and Brown life. The past few years have shown that American populism furthers the danger of not just police brutality but also of vigilante or mass scale white nationalist violence as what we’ve witnessed recently in places like Charleston, South Carolina and El Paso, Texas. White nationalists traveled to both Charleston and El Paso to commit mass murder in the name of American patriotism. These factors and the histories they belong to provide one rationale for Black-Brown solidarity. This is not to suggest that each group experiences oppression equally and despite how they are most commonly singled out as primary targets for law-and-order regimes. What it does suggest is that police terror is rife at the border and in our cities for a reason. White nationalism stirred by slogans such as “Make America Great Again” is informed by a distinctively anti-Brown and anti-Black narrative that derives from the purview of the plantation overseer and the settler colonizer. There is thus a rationale for a comprehensive challenge to oppression and that is inherent to the phrase, Black-Brown.

- Afro-Latinidad must be foregrounded and not obscured within Brown political thought. By this I refer to the limitations of terms such as Hispanic or Latinx within conversations regarding solidarity. Slavery and Black liberation histories are not reducible to the U.S. nation state. The vast majority of persons referred to as Latinx derive from predominantly indigenous or African origins. Both origins tend to be obscured due to an implicit aspiration to whiteness and assimilation that is identifiable in ambiguous and Eurocentric terms such as Hispanic or Latinx. Utilizing anti-Black discourse in defense of Brown spaces is an insult to many of our own ancestors. The African slave trade was the edifice from which capitalism was developed across the Americas (not to discount the salience of indigenous slavery or exploitation). This was especially true in the U.S. nation state. The ambiguity and far-reach of a term Latinx tends to hide class privileges and allows for people with Hispanic surnames and yet who were reared amidst or experience the security of white privilege to be elevated and celebrated as spokespersons on behalf of all Hispanic surnamed people, most of who are racialized as Brown and Black. There is thus a racial and colonial hierarchy embedded within terms such as Latinx and Hispanic. This ambiguity is one of the reasons why anti-Black ideas or beliefs are not just obscured but also furthered within Latinx communities. To be sure, indigenous struggles against conquest and settler colonialism are also obscured by the term Latinx. I use the term Brown to help reclaim some of this and to unsettle the whiteness within the term Latinx. While the term Brown can also obscure Black histories in Latin America and can obscure the salience of Afro-Latinidad, we still face the reality that there is a Brown experience to be referred to within our organizing and intellectual cultures and that should be linked to Black politics via an ethics of solidarity. This is what movements like the Chicano Movement were all about. They were movements or efforts inspired, in large part, by Black liberation struggles and that centered Browness as a reference to indigeneity that could help to mobilize more effective coalitions against white supremacy and imperialism. The term, Brown, I argue, has use and that’s why it’s so often fused to the word Black in conversations regarding solidarity. Brown, as sutured onto Black via a hyphen, refers to a racialized non-white positionality that does not presume a place amidst Black liberation histories or indigenous decolonization struggles nor can it be subsumed by either of them. Brown struggle relates to both and should not be forced to float around in obscurity. Bearing this in mind, it bears repeating that Black-Brown solidarity in the U.S. should be strengthened by and should not help erase the African presence within Latinidad.

- There’s nothing wrong with cliquing up. But if or when we defend our varrios from harm we cannot forget the original source of such harm. This at least holds true in a city like Chicago. Brown or Latin gangs here originated, to large extent, as self-defense units against segregationist violence first practiced by white ethnic gangs Those white ethnic gangs were formed as a way for European immigrants to distinguish themselves from the perils of working-class life that they initially experienced alongside Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and African Americans. White supremacy gave them that opportunity and in order for them to seize upon it. And so, they practiced anti-Brown and anti-Black violence. The history is irrefutable. Clikas (Chicano slang for neighborhood gangs or “cliques”) like the Latin Kings, Latin Eagles, Young Lords and others evolved from sociedad mutualistas with names such as La Hacha Vieja. These were mutual aid societies forged via the praxis and thought of compadrazgo and that travelled with Mexicans and Puerto Ricans to Chicago area neighborhoods like La Villita, Pilsen, Lincoln Park, and Logan Square. Sociedad mutualistas correspond with the salience of fictive kinship in African American history. Out of that base of mutual aid, Mexican and Puerto Rican youth began to fight back. They formed clikas to defend their families from the violence of white ethnic gangs. Those white ethnic gangs would later have a strong influence on local law enforcement and politics which implanted segregationist violence as an imperative of policing. Black history in Chicago is similar. Black gangs such as the Vice Lords and Black P. Stones were formed to defend Black communities from the same legacy of segregationist violence. The original impetus for both Black and Brown gangs in Chicago thus makes tensions between Black and Brown gangs seem rather illogical.

- Brown social movements are indebted to Black social movements. Some of the aforementioned Latin gangs were inspired by the Black power movement of the 1960s and to the extent that their neighborhood gangs evolved into political organizations rooted in an ethics of decolonization. This evolution was especially inspired, encouraged and led by the Illinois Chapter of the Black Panther Party for Self Defense led by their Chairman Fred Hampton. Hampton’s skill at fomenting solidarity between groups, it has been argued, was a major reason why he represented a threat to the status quo, leading to his assassination at the hands of local law enforcement authorities. You can see a similar effect across the United States where either local chapters of the Black Panther Party or other Black liberation organizations inspired the formation of similar organizations within Brown communities or worked directly to help Brown communities organize as such. This is not to say that Brown social movements have merely piggy-backed on Black social movements. There are many unique qualities of Brown social movements and organizations that do indeed get ignored or under-analyzed. Brown leaders have also been persecuted and killed and sometimes due to their emphasis on inter-group and extranational solidarity. This is also not to say that Brown or indigenous social movements have not aided or inspired Black liberation struggles. Lastly, this is not also to say that Black liberation struggle should bear the burden of other oppressed groups. What it does mean is that the images, sound, rhythm, words, and slogans of Black struggles have been inspirational. They have provided an opportunity for resistance that non-Black groups of color should express not just a solidarity with but also a gratitude towards.

- Forgetting legacies of solidarity or failing to connect struggles or histories is an intended outcome of a neoliberal political economy and ethics. The term neoliberalism refers to both a political economy and an ethic of management that derives from the post-Cold War era. An insurgent and overt Black-Brown solidarity threatened the status quo in the U.S. during the 1960s and 1970s. The U.S. nation state responded first with brutal acts of repression towards grass roots political organizations that exhibited these characteristics in particular and that also linked local anti-racist struggles to anti-colonial wars the word over. As Jordan Camp has effectively argued, one of the primary directives of a post-war neoliberal order was to destroy bases of organizing power within racialized groups, disrupt solidarities between them, and disrupt solidarities between communities of color and revolutionary struggles in the global south. The assassination, criminalization, and incarceration of movement leaders created a critical void within Black and Brown communities and especially regarding the intellectual work needed to visualize and mobilize solidarities. This war against social movements also culminated with chaos stirred by the sudden arrival of crack cocaine and military grade weaponry within our communities. It also corresponded with the advent of a prison industrial complex to which so much of our Black and Brown communities have been relocated over the past three decades. As voids of critical leadership and education were created and as Black and Brown prison populations swelled, the critical education component inherent to Black power and Brown power movements was also transferred from Black and Brown communities to places like universities within which academic units are often expected to function like insurgent collectives formed in Black or Brown communities but never truly have (or arguably will). Universities tend to function according to the mandates of neoliberal capitalism and its emphasis on individual excellence, healing, reform, and other therapeutic maneuvers intended to quell critical discord, de-emphasize a focus on interrelated structures of oppression, and disassemble solidarities. The logic of radical solidarities of the past have been ridiculed as naïve and ineffective while new generations have gravitated towards conceptualizations of collective resistance as futile and oppression as ontological, permanent, or inevitable. The irony is that Black and Brown liberation struggles created the opportunity and space for those same critical theorizations to take place and become trends within institutions of privilege. This, I believe, was not by chance. It abides by the same strategy of division and dispersion that the state used to crush social movements and solidarities of the previous generation. Neoliberalism, moreover, is driven by an ethics and politics of multiculturalism which depends upon groups and their epistemologies being separated from one another, conceptualized as distinct rather than interconnected, and placed on display incrementally and in ways intended to benefit colonial institutions more than imperiled communities. One antidote to the isolating and compartmentalizing ethics of neoliberalism and its class-driven divide-and-conquer ethics is a recommitment to solidarities of which the Black-Brown version remains vital.

***

Dr. John David Márquez is an Associate Professor of African American Studies and Latinx Studies at Northwestern University in Evanston IL. He is the author of Black-Brown Solidarity: Racial Politics in the New Gulf South (University of Texas Press) and the forthcoming Genocidal Democracy: Neoliberalism, Mass Incarceration and the Politics of Gun Violence (Routledge). His essays on race and class have appeared in American Quarterly, South Atlantic Quarterly, Latino Studies, and Subjectivity. He has appeared on CNN, NBC Nightly News, MSNBC, and C-SPAN and other media outlets as a political pundit.