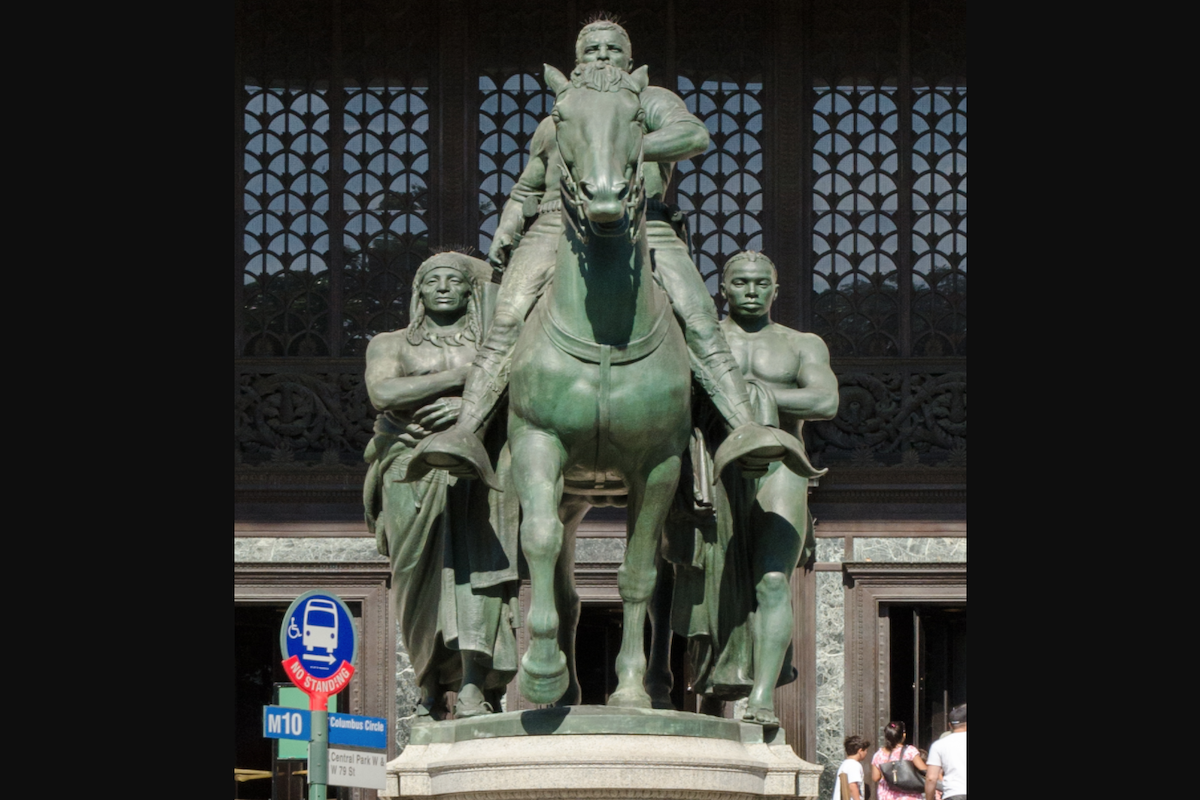

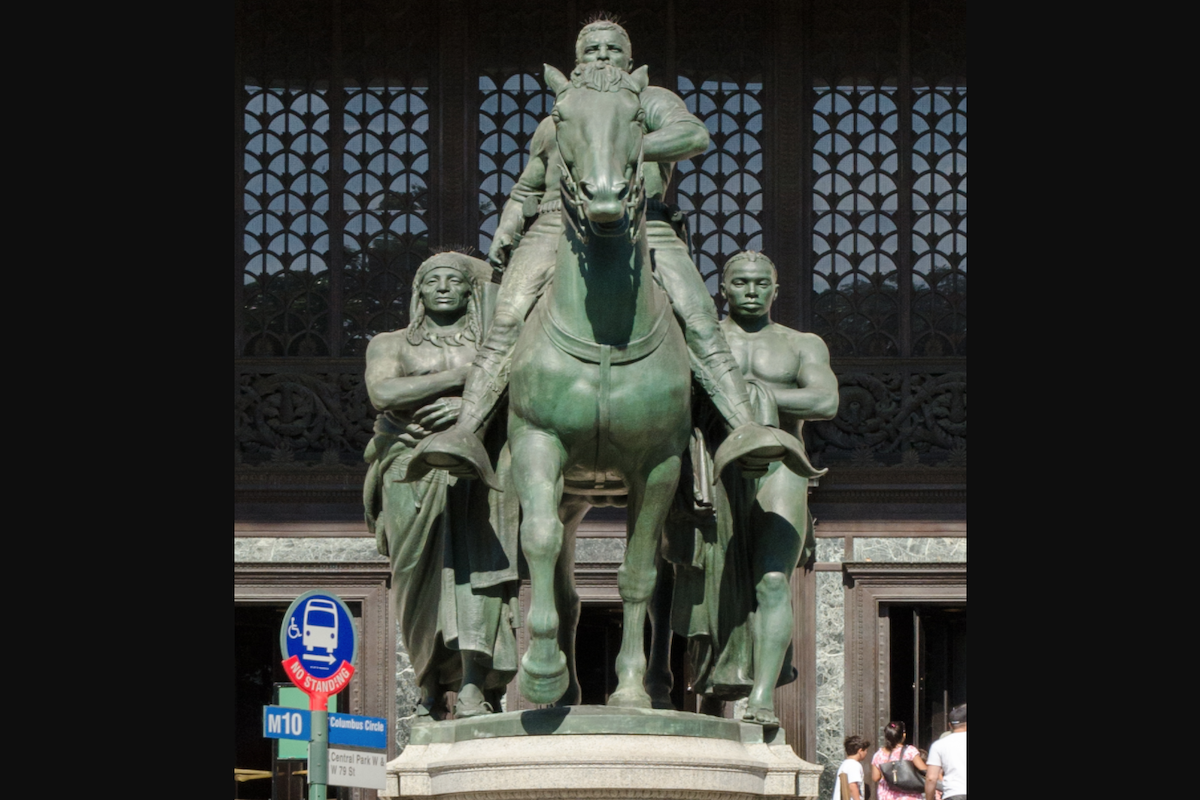

The Theodore Roosvelt statue at the American Museum of Natural History in New York (Photo by edwardhblake/CREDIT)

On Sunday June 21, New York City Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the American Museum of Natural History will remove a prominent statue of President Theodore Roosevelt from its entrance. The removal responds to years of accusations that the statue symbolizes colonial expansion and racial discrimination. The statue depicts Roosevelt on horseback with a Native American and an African man standing next to the horse. In his decision, Mayor de Blasio explained that to many, the statue explicitly depicts “Black and Indigenous people as subjugated and racially inferior.”

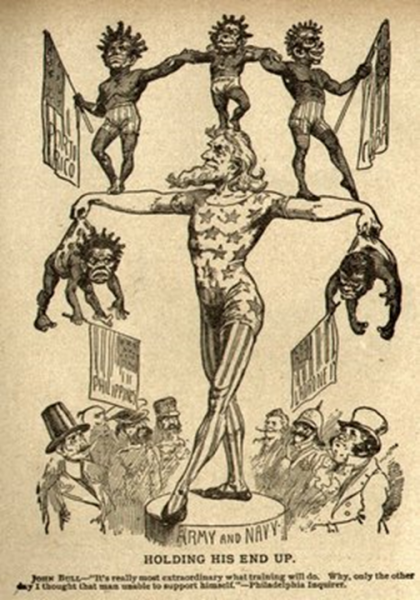

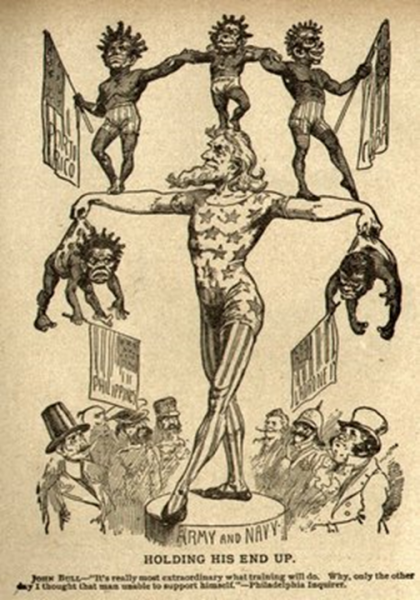

It would be wise to remember that T.R. first became famous during the United States’ intervention in the War of Independence in Cuba in 1898. His actions before, during and after the United States went to war with Spain helped to make the U.S. an imperial, colonial, and global power. Notice that I’m using “global” to signal a difference. Until 1898, and excluding Hawaii, the United States had expanded rapidly through the northern part of the Western Hemisphere. Make no mistake, that expansion had been colonial and imperial, but it had been continental. 1898 would change that, and the United States would emerge from it as a global colonial empire. T.R. was instrumental in making this happen.

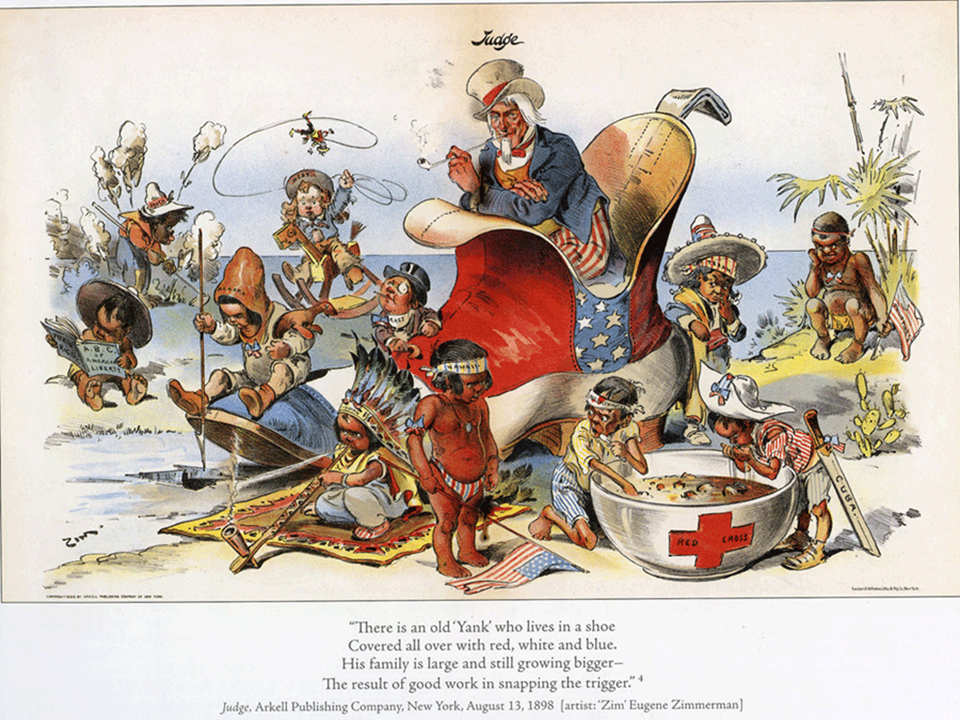

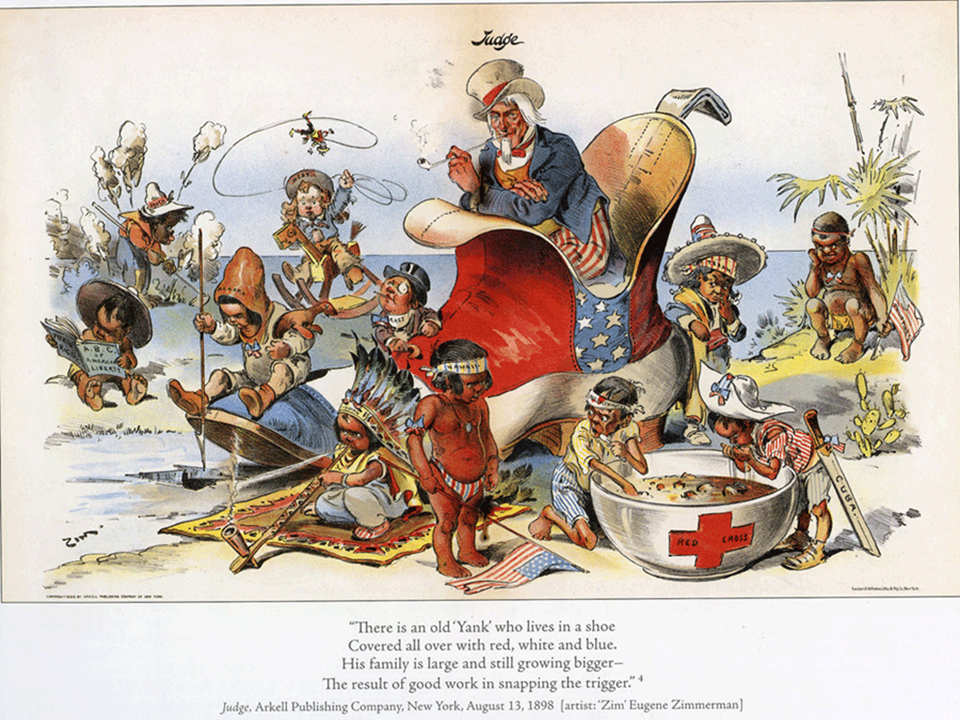

Since 1895, Cuban rebels had retaken their long struggle for independence from Spain. The U.S. wanted both markets and territories in Cuba and Puerto Rico, thus supporting the Cuban rebellion and Puerto Rican separatists operating from New York might have been a logical path to follow. The racial discourse of the era, however, did not permit the U.S. to do so. The prospect of these islands being in control of a band of Indians, former African slaves and Spaniards so intrinsically mixed, abhorred many U.S. politicians who did not believe that Cubans (much less Filipinos and Puerto Ricans) could keep the peace because independence would be followed by racial war and instability. Hence in 1895, when the Cuban rebellion started with the Grito de Baire, the U.S. followed a path of neutrality, which actually favored the Spaniards.

By 1897, it was evident that sooner or later the Cuban rebels would win the war. For three years the Cubans had been destroying the logistic infrastructure of the island, rendering the Spanish army incapable of concerting major military actions. The assessment of the supreme Spanish commander in Cuba, Valeriano “the Butcher” Weyler, was that the rebels “had brought the Spanish army to the brink of defeat.” This situation left the President William McKinley and his administration with two choices: to accept Cuban independence or military intervention.

On February 15, 1898, the second-class battleship Maine exploded in Havana Harbor. Though likely an accident, the McKinley administration took the opportunity to intervene in the war and dictate the future of Spanish possessions in the Caribbean and the Pacific.

Theodore Roosevelt, who had been the first reviewer of Alfred T. Mahan’s most influential book, The Influence of Sea Power upon History, agreed with the naval strategist that the road to national grandeur was through sea power, and was thus committed to obtain an interoceanic canal (eventually built in Panama) as well as the bases to protect it, to project American economic and military power. Both Mahan and T.R. viewed the war in Cuba as an opportunity to exploit their positions with respect to the enlargement of the navy and merchant marine, and the acquisition of bases. After the explosion of the Maine, T.R. fervidly advocated for the prompt opening of hostilities.

It is worth looking at the way the United States intervened in Cuba. As Congress debated intervention, T.R., his mentor Admiral T. Mahan, Henry Cabot Lodge and the McKinley administration opposed the passing of the Teller Amendment, which stated that the United States did not intend to annex Cuba and that it would leave as soon as the island had been pacified.

The administration, having been forced to accept the amendment, conducted a campaign designed to depict Cubans, Filipinos and Puerto Ricans as unworthy allies and savages. The first step was to declare the campaign in Cuba as “neutral intervention.” The U.S. did not even concert a formal alliance with the Cuban rebels, and excluded them from the front lines.

On February 25, just ten days after the sinking of the Maine, T.R., as assistant secretary of the Navy, sent the famous telegram to Commodore George Dewey, ordering him to advance full speed to the Philippines. A quick naval battle opened the Philippines to the United States. Commodore Dewey’s accomplishment in Manila got the U.S. deeply entangled in East Asian affairs. Hence, the annexation of Hawaii became a priority as it could be justified as a support base for defending the Philippines. On July 6, 1898, the United States annexed Hawaii.

On July 3, Admiral Pascual Cervera y Topete’s fleet was destroyed by the U.S. Flying Squadron while trying to break the American blockade in Santiago de Cuba. At that moment, the war was practically over. Two weeks later, on July 17, the Spanish garrison in Cuba surrender. Plans to invade Puerto Rico continued at full speed even as Spain frantically tried diplomatic channels to end the war and keep its last possession in the Caribbean.

Theodore Roosevelt had left his post as assistant secretary of the Navy to lead a volunteer cavalry regiment, the Rough Riders. His regiment participated in the battle of San Juan Hill in Cuba. As several historians have pointed out, in his writings he misconstrued the performance of African American soldiers which he considered slightly better than the Cuban rebels when firmly led by White officers.

His thirst for adventure quenched after the Battle of San Juan Hill and the Spanish surrender, Theodore Roosevelt wrote a personal letter to Senator Henry Cabot Lodge urging him not to make peace until “we get Porto Rico.”

Lodge assured Roosevelt that the administration was “fully committed to the larger policy we both desire.” President McKinley’s administration had decided in early June, to annex Puerto Rico “in lieu of indemnities,” and the physical presence of the U.S. military on the island would secure it. On July 25, the American forces invaded Puerto Rico.

On August 12, Spain signed an armistice on American terms. The Cubans, who had been excluded from American front lines operations, were also excluded from the deliberations of the armistice and the signing of the Treaty of Paris, and so were the Filipino rebels, and the Puerto Rican delegates to the Spanish Cortes.

As a result of the war with Spain, the United States gained full control over Puerto Rico, Guam, Wake Island, and the Philippines, and limited control over Cuba, by virtue of the Treaty of Paris of December 10, 1898. The term “pacification” in the Teller Amendment allowed the McKinley administration to first establish a military occupation and ultimately to impose the Platt Amendment to the Cubans. This clause dictated that Cuba could not compromise its independence by entering a treaty with a foreign power. Cuba’s government could not assume debts that could not repay, and the U.S. government retained the right to intervene to preserve its independence and the maintenance of a stable government. The amendment also granted the U.S. perennial rights over Guantanamo. The Platt Amendment defined American-Cuban relations for almost half a century.

That Puerto Rico and the Philippines came to be colonial possessions of the United States, while Cuba became an American de facto protectorate, did not stem from historical accident but rather from a calculated design. At the core of that calculated design’s matrix was the belief that the inhabitants of these archipelagos were both racially and culturally inferior and thus unfit to govern themselves.

Theodore Roosevelt shared these views. His much-hyped actions in Cuba made him famous, and he became governor of New York in 1899. The following year, he was selected for Vice President spot in President McKinley’s successful run for a second term. T.R. became President in 1901 after McKinley’s assassination in September, a position he held until March 4, 1909.

He was an ardent believer of the racial tenets of the moment and in particular, that “civilized nations” should act as protectors of “barbarous” ones. He added his Corollary to the Monroe Doctrine, which simply put meant that the U.S. would not only oppose outside intervention in Latin American affairs, it would also police the area and guarantee that these countries met their international obligations.

A series of interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean followed. Perhaps the most famous case of Roosevelt’s “speak softly but carry a big stick” approach happened in 1903, when his administration facilitated (more than likely engineered) the secession of Panama from Colombia (after the Colombian parliament would not agree with his terms for the building of an interoceanic canal). With Panama as an independent country, T.R. attained his long-sought goal of an Isthmian canal fully under American control.

T.R.’s big stick in dealing with Latin America and the Caribbean would be felt for generations. He may have promoted progressive policies domestically but for his administration, Latin America was his backyard—and to this day American policymakers continue to treat the area as such.

As for those who see the removal of the statue as erasing history, consider this—statues are not history but celebrations of people and narratives. Many times, those narratives are the same ones that continue to enslave us for they tell a story in which White men built this world and delivered us from obscurantism and savagery. The statue does in fact present the Black and the Native as inferior and subjugated—and what is worse, T.R. not only believed this but his foreign policy was guided by it. Thus, it is time for the statues to come down and to fully engage with our past, with our histories, and with its long term repercussions.

***

Harry Franqui-Rivera, Ph.D. is historian and author of Soldiers of the Nation: Military Service and Modern Puerto Rico, 1868-1952. He tweets from @hfranqui.