In this March 14, 2020 file photo, a cleaning crew works at a Transportation Security Administration checkpoint at John F. Kennedy International Airport in New York. (AP Photo/Kathy Willens)

By Rogelio Sáenz

This is the second follow-up on my analysis of COVID-19 cases and deaths among Latinos, which I initiated in early May.

There have been a variety of significant shifts concerning the pandemic over the last month.

First, the U.S. is now closing in on 3 million confirmed cases and 150,000 deaths. While the U.S. represents about 4% of the world’s population, the country accounts for approximately one-fourth of the COVID-19 cases and deaths globally. Second, politicians throughout much of the country have taken daring steps to open their states for business, even though public health experts have clearly noted that we are not ready to do so and that there will be dire consequences for opening up the economy prematurely. Third, over the last couple of weeks, the predictions of the experts have been realized, as we are seeing major spikes and daily record-setting numbers of new infections and hospitalizations in the southern and western parts of the nation with Arizona, California, Florida, and Texas representing major hotspots. Fourth, the demography of people contracting the virus has shifted with younger people in their twenties and thirties contracting the virus at higher rates. Fifth, while we have not seen rising deaths over the last few weeks, unfortunately, these may increase over the coming weeks as some people who are catching the virus succumb to it or spread it to older people who are more vulnerable. Sixth, in the midst of the pandemic, the mask has increasingly become a political symbol associated with weakness and the imposition on personal freedom among President Trump and many conservatives. Finally, in early July, the New York Times released the most comprehensive work to date which shows the heavy toll that the virus has had on Blacks and Latinos nationally but also throughout much of the country.

As we will see below, over the last month, the data are picking up some of these trends related to COVID-19 cases and deaths among Latinos. As I did last month, I use data from the COVID Tracking Project to conduct the analysis for COVID-19 cases and deaths among Latinos across states, with the data updated on July 5. I need to point out that problems, which I have discussed earlier and as will be obvious below, still plague the data, most notably that a significant share of cases and deaths do not have race and ethnic identification.

Continued Widespread of COVID-19 Cases Among Latinos

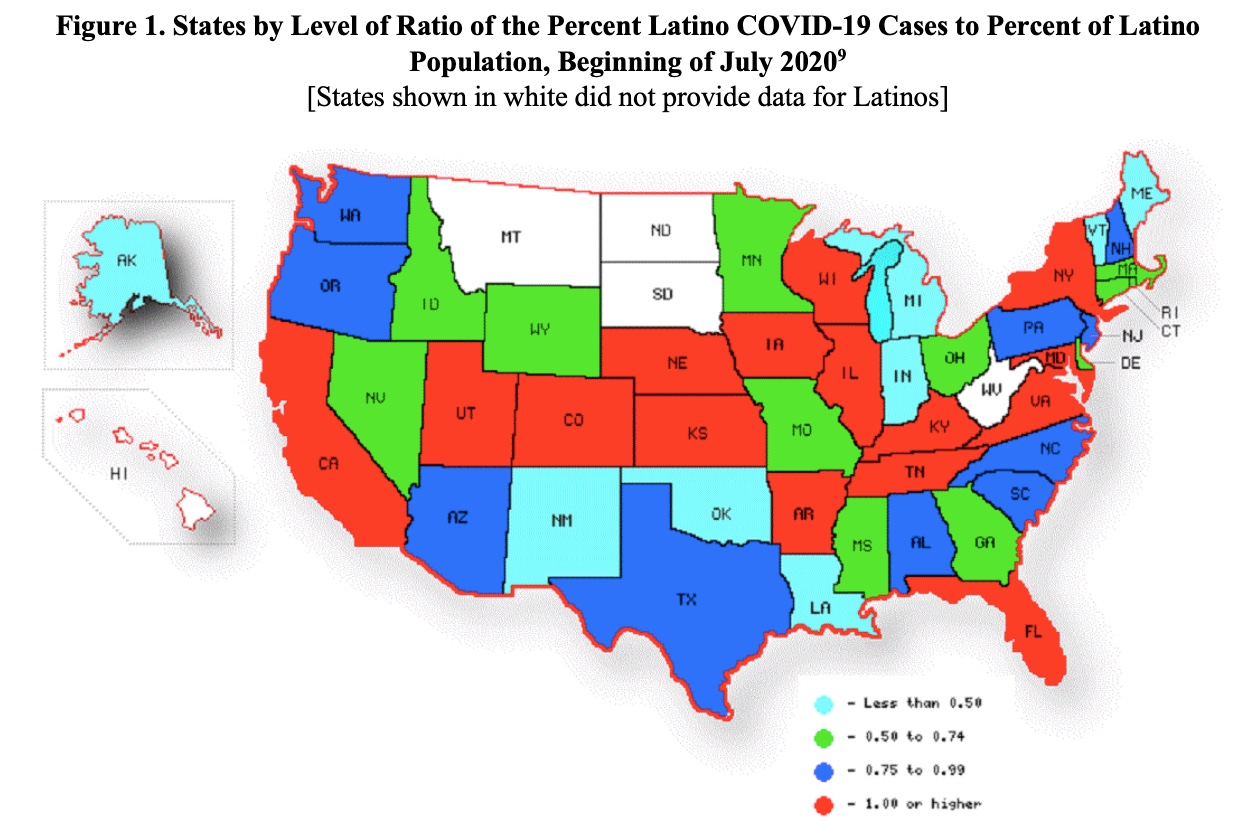

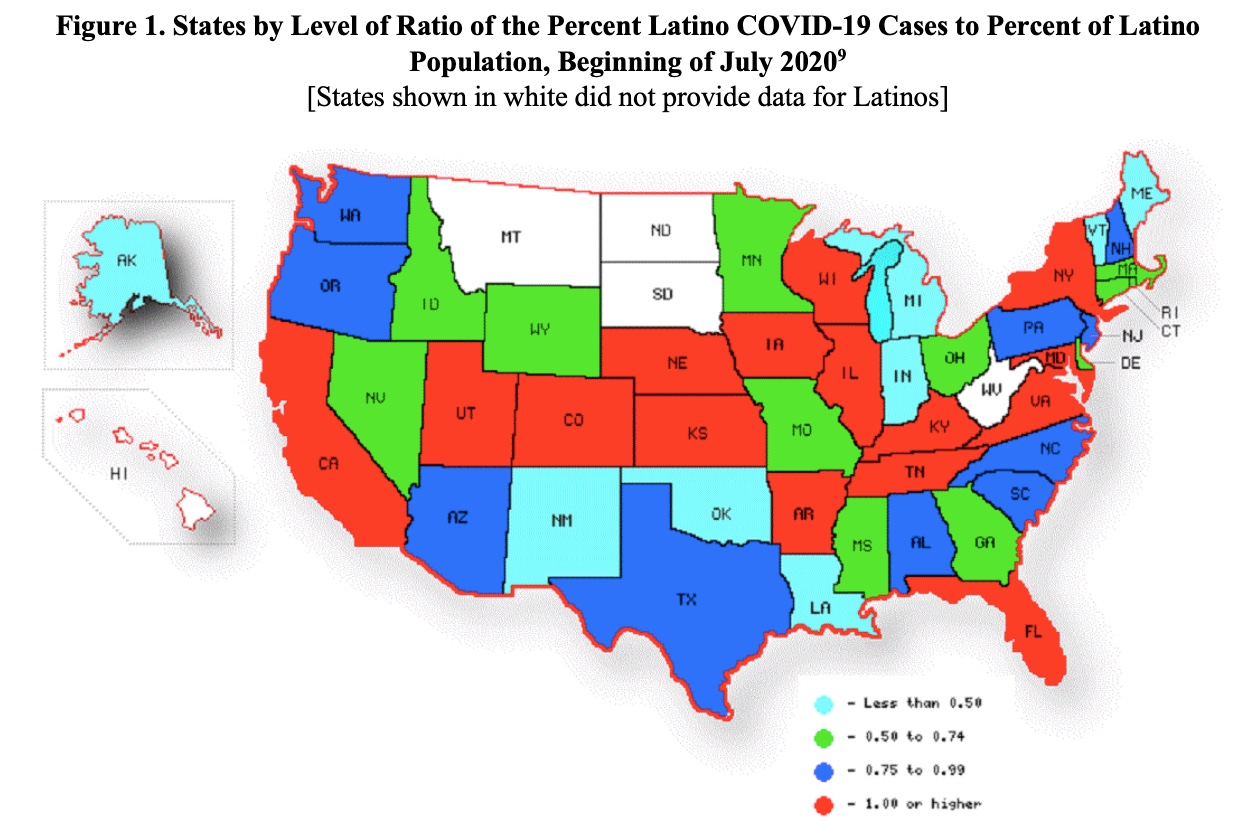

As we have observed over the last couple of months, Latinos are disproportionately represented among people catching the virus relative to their percentage representation across almost all states —45 of the 46 states and the District of Columbia— that provide this information for Latinos (Figure 1). Once again, New Mexico is the only state where Latinos are underrepresented among COVID-19 cases. While Latinos make up 49% of New Mexico’s population, they account for 31% of persons who have contracted the virus. Nonetheless, New Mexico has experienced an upswing in cases and recently there was an outbreak at the Otero County Detention Center along with several deaths among inmates.

Latinos are more than twice as likely to be among people who have contracted the virus in 35 of the 46 states. Yet, in 10 of these states, Latinos are more than four times as likely to be among COVID-19 cases relative to their percentage share in the overall population including Tennessee (33.8% of cases versus 5.5% in population), Nebraska (58.6% versus 11.2%); Minnesota (27.2% versus 5.4%); Wisconsin (34.4% versus 6.9%); Iowa (29.4% versus 6.1%); Kentucky (17.3% versus 3.6%); North Carolina (46.0% versus 9.6%); Virginia (44.9% versus 9.6%); Kansas (50.2% versus 12.0%); and South Dakota (16.0% versus 3.9%). These states, located in the South and Midwest, have had outbreaks in the meatpacking industry, where Latinos represent the major part of the workforce.

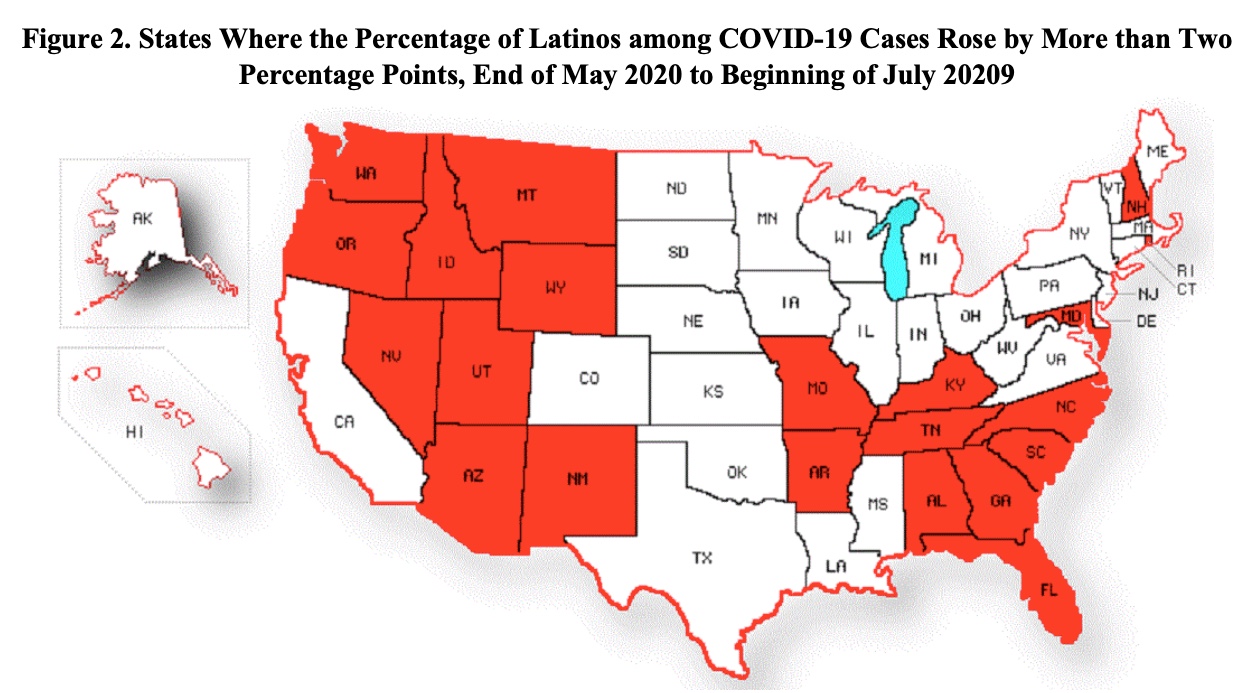

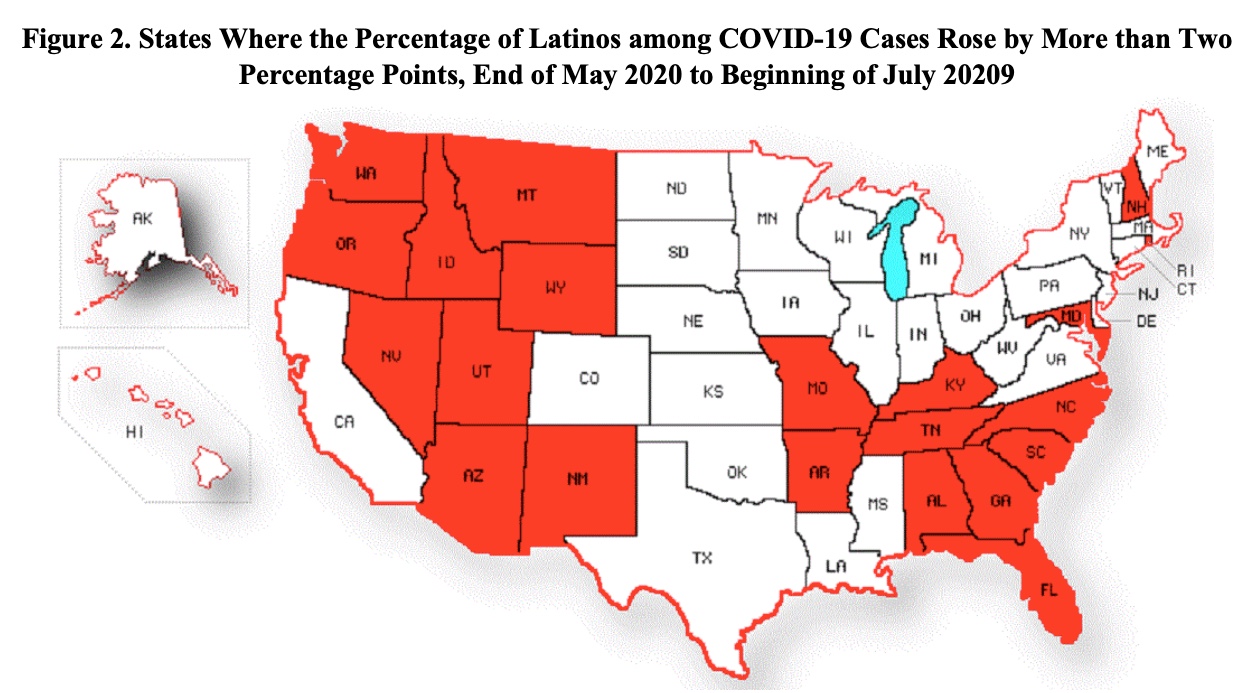

Overall, during the last month since the analysis I did at the beginning of July, 37 of the 44 states that have data for these two time periods (between the end of May and the beginning of July) experienced a rising percentage share of Latinos among persons who have contracted the virus. Twenty-one states, principally located in the South and West, saw increases of at least 2 percentage points in the percentage of the state’s cases that were Latino over this time period (Figure 2). These states include many that have taken more aggressive steps to open larger segments of business and where we are seeing the emergence of hotspots over the last few weeks. The five states that experienced the strongest rise in the percentage share of the cases that are Latino are Arkansas (rise from 10.7% at the end of April to 25.1% at beginning of July), Arizona (34.6% to 45.7%), North Carolina (35.5% to 46.0%), Georgia (16.4% to 24.8%), and New Mexico (24.3% to 31.3%).

Increasing Overrepresentation of Latinos Among the Deceased

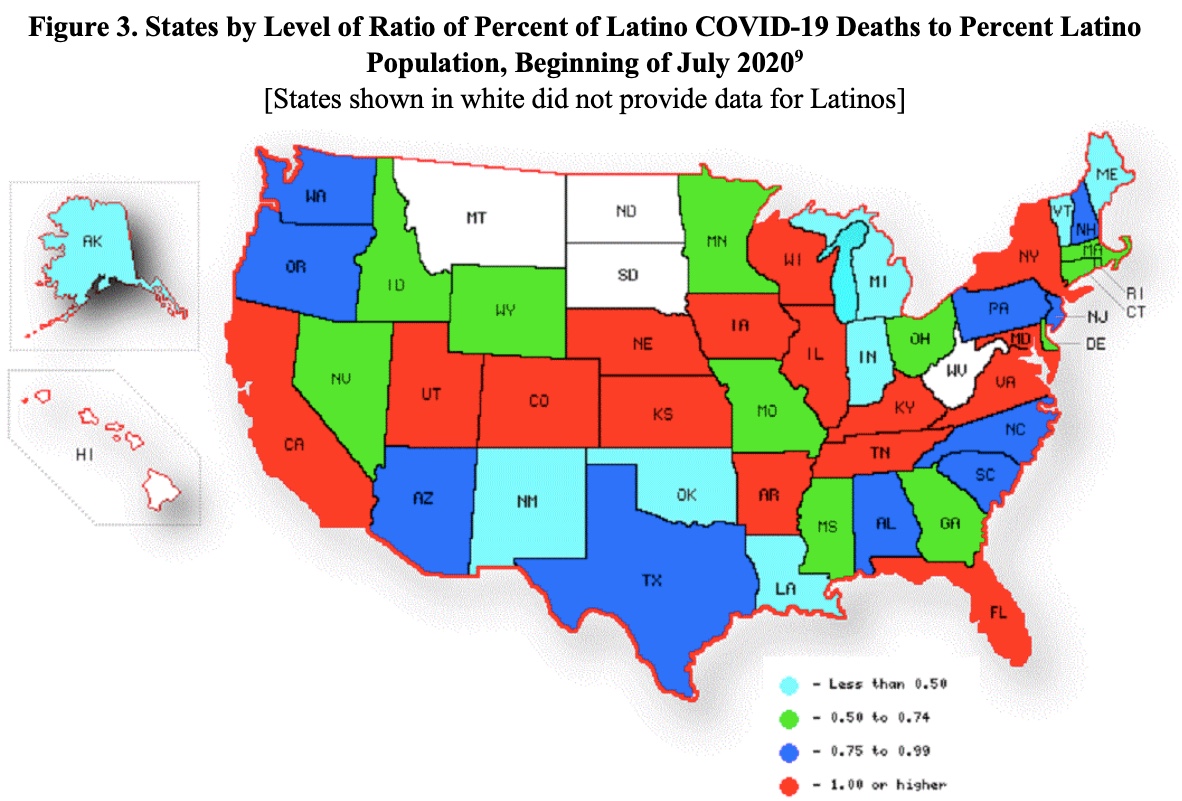

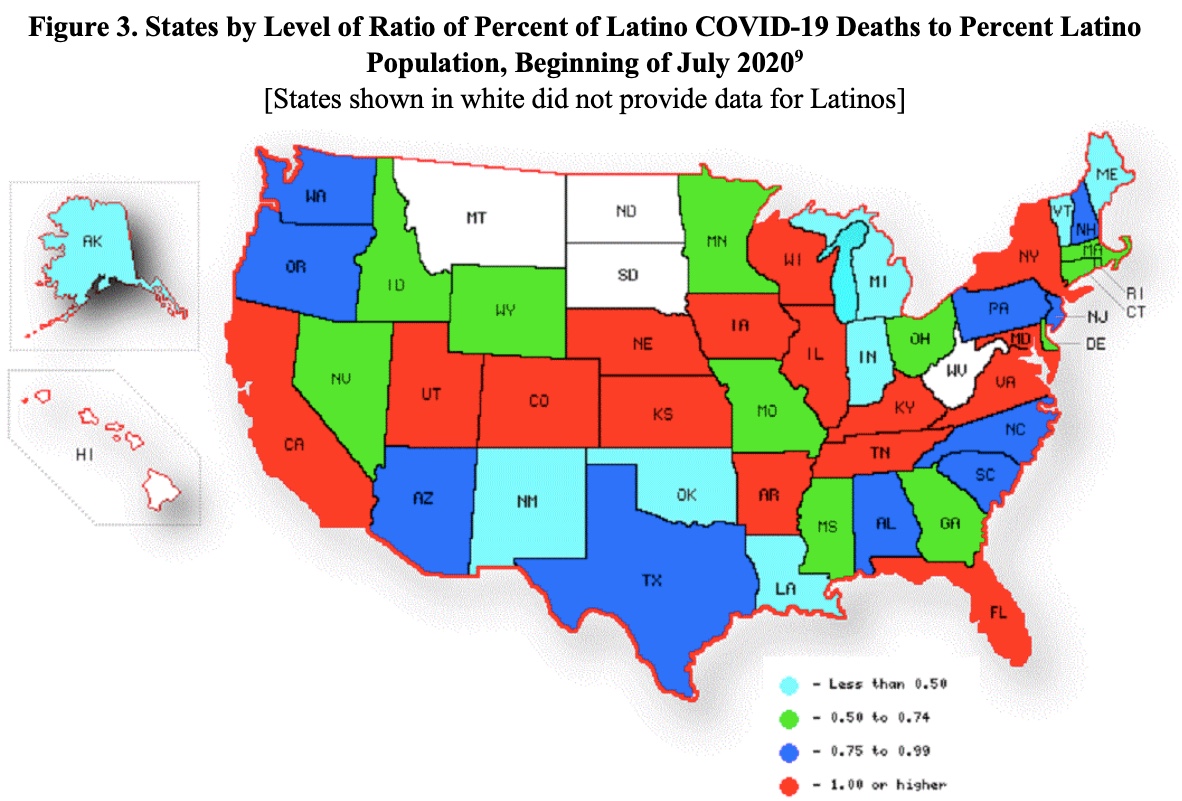

We have seen that, as a whole, Latinos have been disproportionately among persons who are succumbing to COVID-19. Nonetheless, we have recently seen growing numbers of states where Latinos are disproportionately overrepresented among the dead, rising from one at the beginning of May to six at the start of June. The upward swing continued this past month as we now observe 16 states where the percentage of persons who died due to COVID-19 surpasses the Latino percentage of the overall population (Figure 3). While the 16 states are located across the nation’s four regions, the largest segment are in the South (seven states) and Midwest (five states).

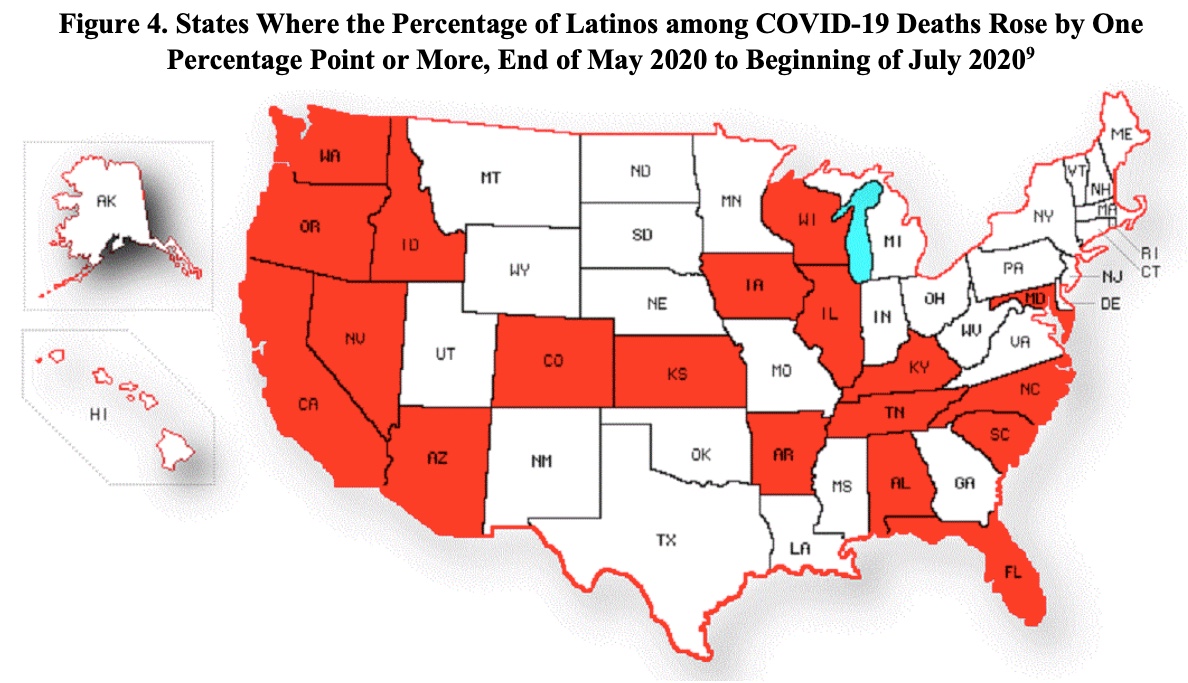

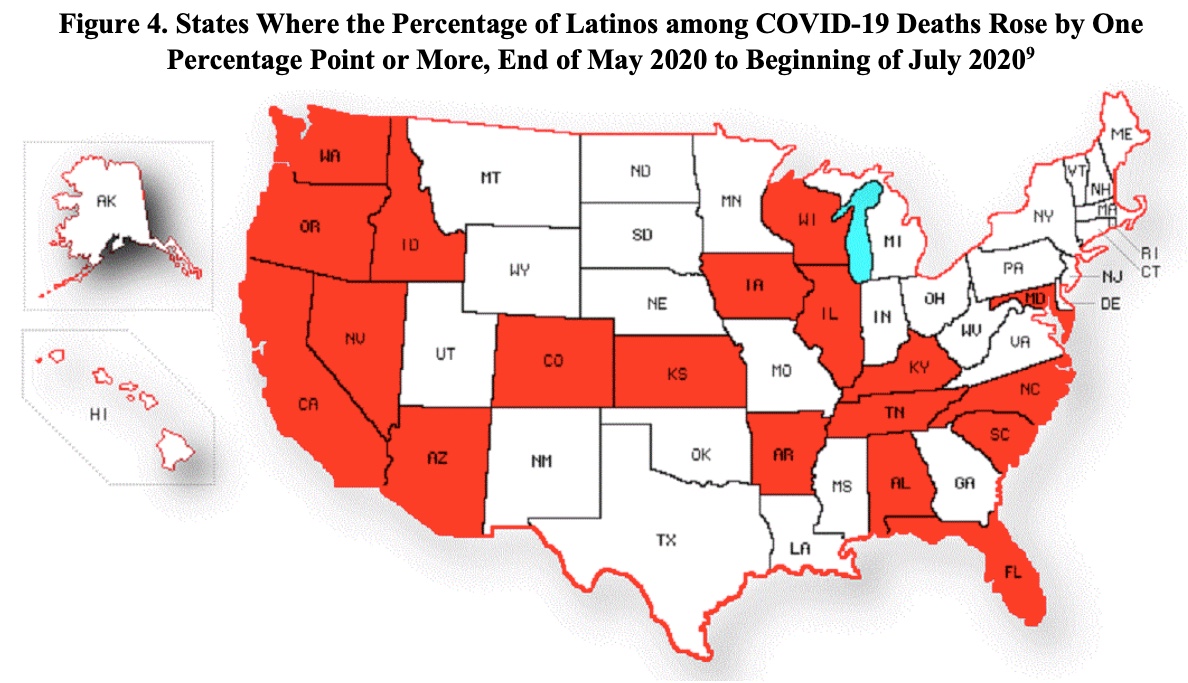

As is the case with COVID-19 infections, 31 of the 42 states for which there are Latino mortality data for the last two time periods (between the end of April and the beginning of July) experienced increases in the Latino percentage share of people dying from COVID-19. Twenty states had an increase of at least one percentage point. These states are primarily clustered in the South and West (Figure 4), as we observed with COVID-19 cases above. Seven states had an increase of over three percentage points in the percentage share of deaths among Latinos: Arkansas (rise from 2.5% at the end of April to 8.3% in the beginning of July); Arizona (20.0% to 24.8%); Florida (23.7% to 27.3%); North Carolina (6.0% to 9.5%); California (38.1% to 41.6%); South Carolina (1.1% to 4.5%); and Washington (9.3% to 12.6%).

It is clearly evident that over the last month, Latinos experienced an upsurge not only of infections but also deaths associated with COVID-19, particularly in the South and West.

What About Texas?

Texas is a puzzling case. It differs from other states with large Latino populations that have experienced the largest increases in their percentage share among COVID-19 cases and deaths, such as California, Nevada, New Mexico, Colorado, and Florida. Texas is a current hotspot of COVID-19 infections alongside Arizona, California, and Florida, but you would not know it from the trends presented here. In fact, over the last month, the Latino share of COVID-19 deaths in the state declined slightly from 32.3% in late April to 31.5% in early July. In addition, in the recent New York Times analysis identifying areas of the country where Latinos and Blacks have been much more devastated than Whites, Texas did not emerge as one of these areas.8 What is going on?

One of the shortcomings thus far on research examining COVID-19 on the basis of race and ethnicity, including my own, is that we are limited to conducting the analysis solely on cases and the dead that have been identified racially and ethnically. Thus, not all persons who have contracted the disease or have died from it are included in the analysis and the level of these missing data varies across geographic areas. Texas stands out in this respect.

Overall, in the U.S. approximately 39% of COVID-19 cases do not have a race or ethnic identification as is the case for 10% of deaths. In Texas, an astounding 91% of cases and 77% of deaths do not have a race or ethnic identification. The average percentage cases and deaths missing this information based on the states that provide data for Latinos are 25% and 9%, respectively. As such, it is difficult to make much sense of how Latinos are faring relative to COVID-19 in Texas when only a very small share of cases (9%) and deaths (23%) have race and ethnic identifiers.

Conclusions

Nonetheless, overall, across states in the nation, it is clear that since last month Latinos continued to be disproportionately hurt by COVID-19. Over this period, the percentage share of Latinos among people infected with the Coronavirus and that of the deceased have risen widely across the large majority of states. Among the 46 states where data are available, Latinos are disproportionately overrepresented among people infected by the virus in 45 states and are overrepresented among the deceased in 16, up from one in May and six in June. It is obvious that the youthfulness of the Latino population is not protecting them.

Indeed, it is estimated that more than one-fourth of Latinos who have died from COVID-19 are less than 60 years of age compared to only 6% among Whites.8 The surge of COVID-19 cases that is taking place across the South and West will make matters worse and, unfortunately, we are likely to sustain an uptick in deaths shortly given the rising number of people infected with the disease and the rising numbers requiring hospitalization. The continued problems with lack of easy access to testing and difficulties associated with contact tracing complicates matters even more.

We need to continue to stay home if we are not required to go out and if we can work from home. Other individuals who do not have this luxury will need to continue to try as much as possible to practice social distancing, wear a mask, and wash their hands with soap frequently. It is important that people who still refuse to wear a mask in public reconsider their decision, as they put themselves and others at risk of contracting the virus. We need to keep reminding ourselves that we are more than ever connected to each other for our survival in our communities and the world. The failure to follow the guidelines of public health experts puts the lives of precious human beings at risk.

I conclude by drawing on the words of San Antonio mayor, Ron Nirenberg, who in a recent video on Twitter, said, “When we report these facts, for our community, they aren’t numbers. They’re people…Mothers, fathers, brothers, sisters, cousins, grandmothers and grandfathers, aunts and uncles, best friends and co-workers, loved ones and neighbors, San Antonians young and old. Gone.” Let us look after each other throughout the communities where we live.

***

Rogelio Sáenz is professor in the Department of Demography at the University of Texas at San Antonio. He is co-author of the book “Latinos in the United States: Diversity and Change.” Sáenz is a regular contributor of op-ed essays to newspapers and media outlets throughout the country. Twitter: @RogelioSaenz42.

[…] the extremely high levels of missing data on COVID-19 infections and deaths in Texas. I mentioned in my July monthly blog that “Overall, in the U.S. approximately 39% of COVID-19 cases do not have a race or ethnic […]