Stacks of ballot envelopes waiting to be mailed are seen at the Wake County Board of Elections in Raleigh, N.C., Thursday, September 3, 2020. (AP Photo/Gerry Broome)

By Sonja Diaz and Tania Unzueta

The comorbidity of this country’s legacy of racial discrimination coupled with contemporary attempts to undermine our most sacred democratic institution is playing out in real time in a key battleground state: North Carolina. President Trump’s fear mongering escalated when he urged the state’s voters to vote twice—a practice that is illegal and may result in felony voter fraud conviction, even for Republicans. The smoke and mirrors are glaring. In 2017, the North Carolina Legislature exempted absentee voting from its discriminatory photo ID requirement. It is likely the omission was influenced by the fact that this method of voting was used disproportionately by white voters.

Though most Latino eligible voters are concentrated in a handful of key states, their numbers are growing quickly in many states across the country, especially the South. Since Trump’s 2016 victory, the number of Latino voters in North Carolina has increased by 25%, with at least 219,000 new registered voters. The power of this growing electorate was evidenced in the 2018 midterms, when North Carolina experienced a surge in Latino voter turnout, a pattern that was expected to continue during this 2020 election cycle if voters were mobilized to cast a ballot without jeopardizing their health and safety. The growth of the Latino electorate most pronounced in the state’s 8th and 5th Congressional Districts (Republican stalwarts), which saw the fastest growth of Latino eligible voters in the country between 2014 and 2017.

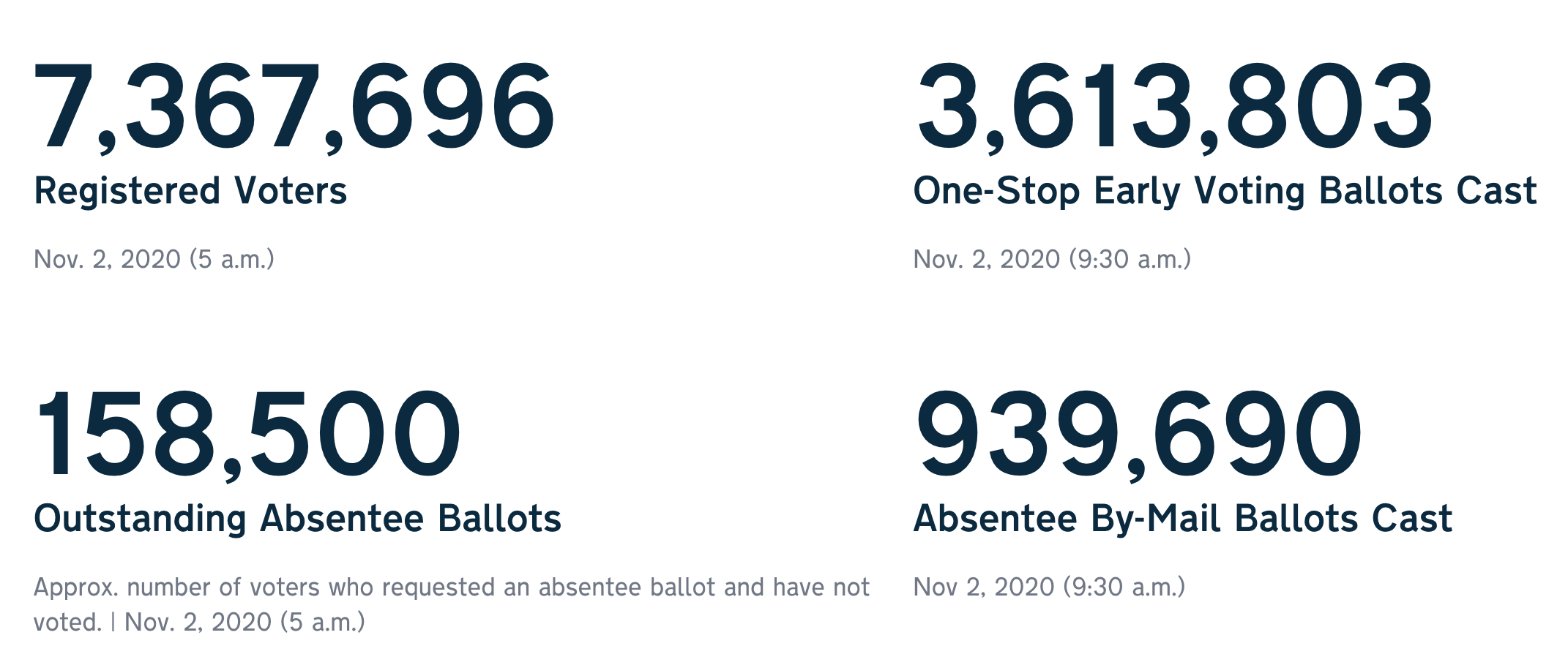

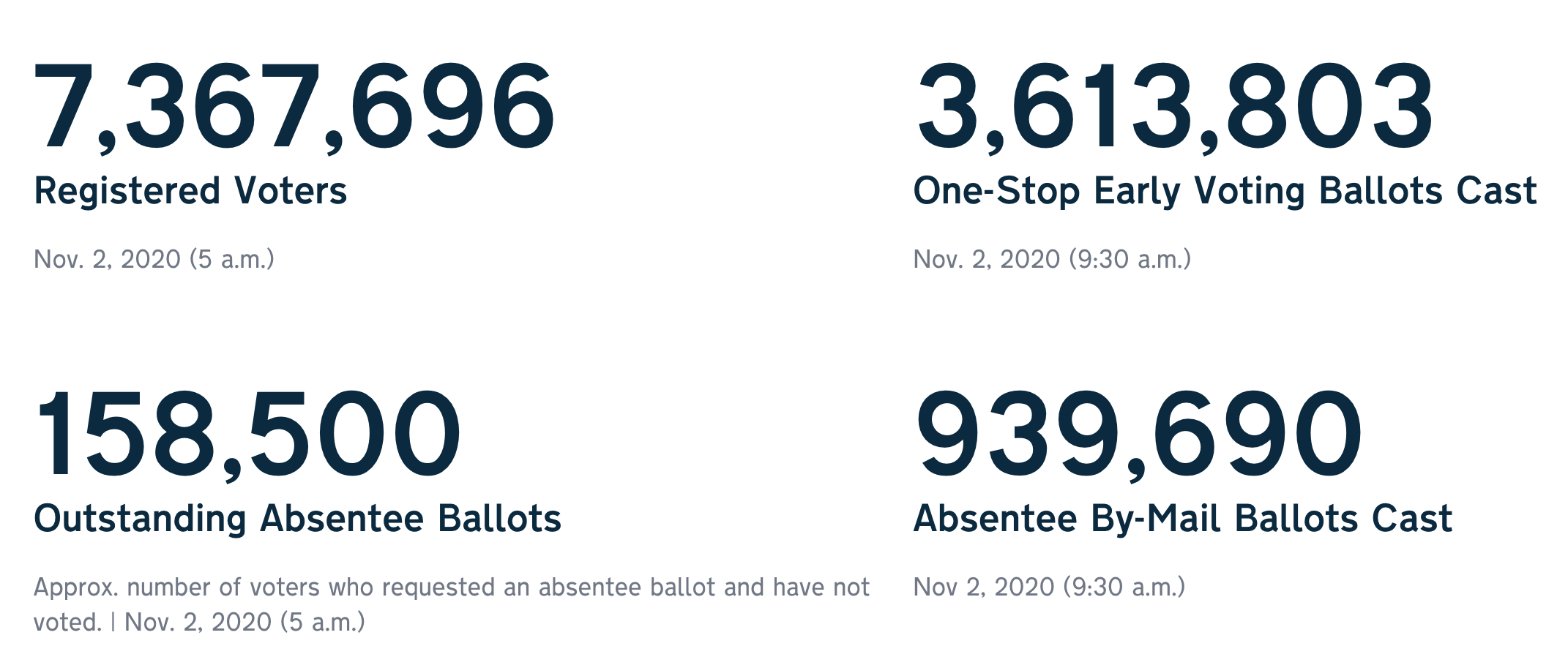

Yet falsehoods about vote-by-mail, including unsubstantiated claims of voter fraud, only serve to deepen American’s distrust of government. To date, 4.5 million North Carolina residents have voted, with almost one million voting through mail-in-ballots, far exceeding that of the last two general elections.

Research shows that vote-by-mail does not increase voter fraud. On the contrary, it increases voter turnout. The Republican assault on a fail-safe method of voting is politically-motivated and a last-ditch attempt to dilute the political power of voters of color. Prior to Trump’s suggestion that North Carolinians should vote twice, voters in the state received an August absentee ballot mailer with Trump’s face on it from the state Republican party, even as the president asserted that voting-by mail “doesn’t work out well for Republicans.”

These contemporary instances of voter suppression not only add a new layer to the North Carolina’s history of racial discrimination, but they compound the barriers that Latino voters already face in navigating the ballot box. The Latino electorate is disadvantaged by their relative youthfulness. They are left out of mobilization efforts that have longed focused on likely-voters, who tend to be older, and whiter.

Navigating arduous voter registration laws in a state like North Carolina is a complicated matrix for first-time voters, and first-time vote-by-mail voters. For starters, all of the information about registering to vote this November is in one language, English. For those that have access to the internet, it takes six clicks from the homepage to reach the general voter registration application with each click decreasing the likelihood that a person will finish and file their application. For those Black and Latino voters who are successful at submitting an absentee ballot, their ballots are three times more likely to be turned away than white voters in the state. Finally, culturally and linguistically appropriate voter outreach to engage Latino voters this cycle has been left up to a small number of non-profit and independent political organizations new to the state, including Mijente.

Early vote data reaffirms that this strategy is leaving Latino voters behind. The 2020 early vote ballots are nearly identical to the electorate four years ago: white voters account for 72% of ballots cast in North Carolina, followed by Black voters at 22%. The lack of investment by both parties in mobilizing non-White, younger voters coupled with egregious forms of voter suppression to diminish the electoral power of Latinos is dangerous for democracy and the economy.

Data has made clear that Latinos continue to be disproportionately affected by this pandemic, and the failure of political parties to turn these voters out early will force them to choose between the health of their family and their political voice on election day. North Carolina’s population is 9% Latino, yet they are almost 5 times more likely to die of COVID-19 than white North Carolinians, even when adjusting for age. Wisconsin is a clear example of what is at stake when people have to choose between their health and their right to vote. The state’s April 7 in-person primary election resulted in an increase of COVID-19 cases. Since North Carolina is the first state in the country to send mail-in-ballots, the fact that the Latino early vote is eerily similar to previous cycles, even though they represent 2% more of the state’s registered voters than they did in 2008, only serves to magnify the racial/ethnic disparities coronavirus morbidity and our electoral politics.

Latinos in North Carolina cannot be relied upon to risk their lives to toil in meat packing plants and agricultural fields, and be expected to overcome de facto and de jure barriers to the ballot box. During this historic election, Latinos need our elected leaders to not only provide personal protective equipment for essential work, but for the ballot box, to overcome renewed attacks on the right to vote, so that their ballot is counted.

***

Sonja Diaz is the founding director of the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Initiative. Tania Unzueta is the political director of Mijente, a Latinx political organizing organization.

maybe learn to speak English. why come and live here, and than not learn the language. ridiculous.