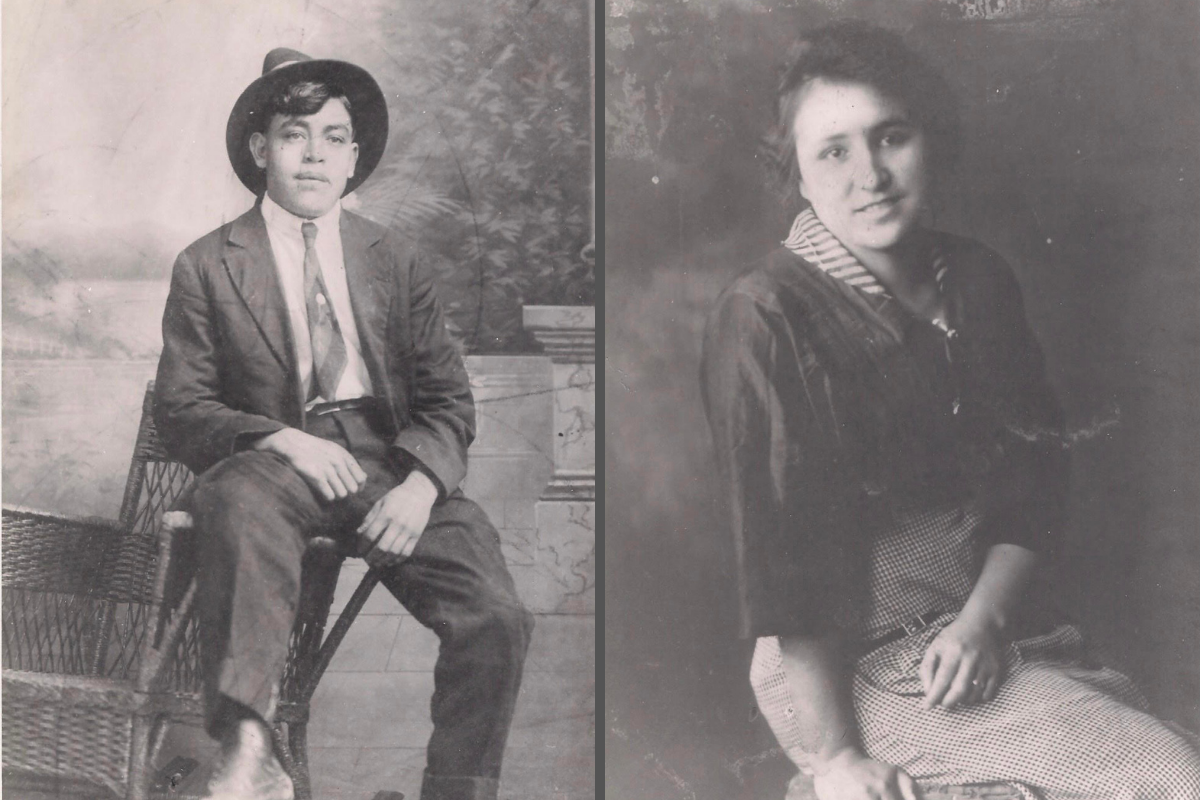

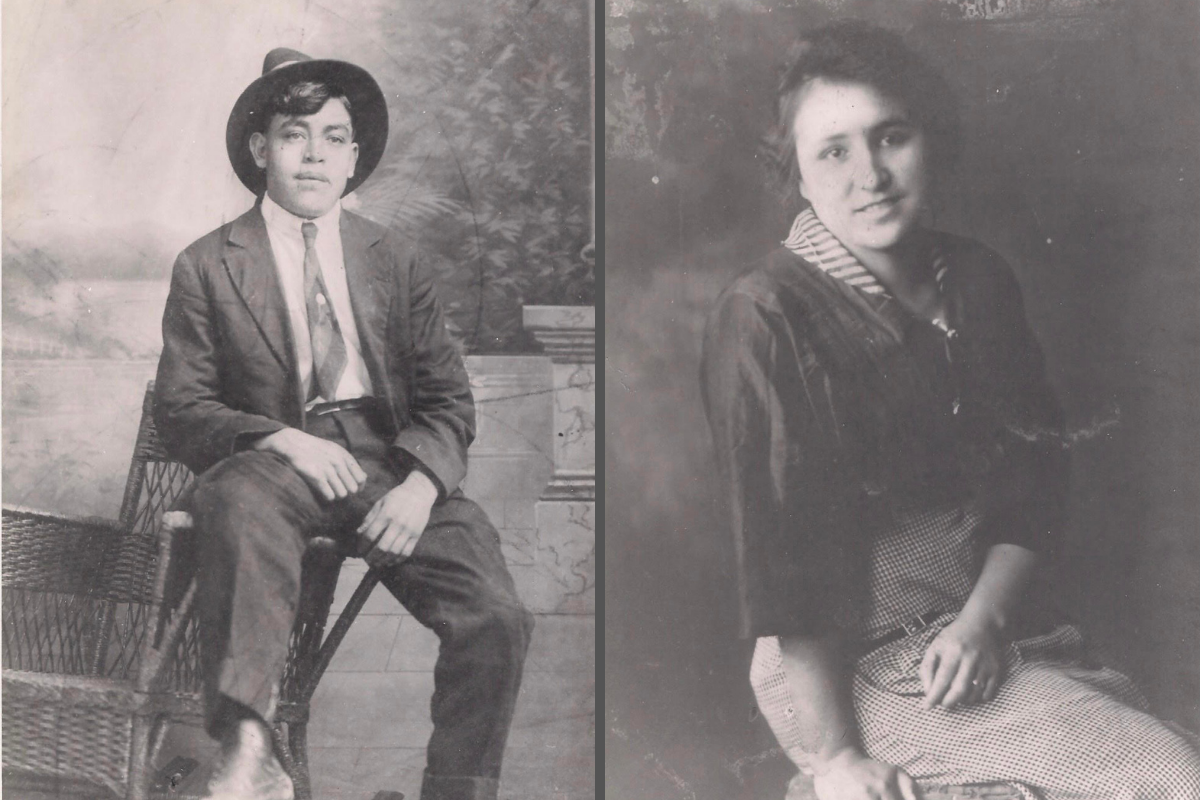

The author’s great-grandparents, Gilbert and Adela Domínguez. Their family believes these photos were taken in the 1920s. (Photos courtesy of Robert Barba)

In September 1920, Gilbert and Adela Domínguez of Raton, New Mexico, lost their two small children in a matter of days.

It was the type of event where the pain is incalculable and yet potentially life-defining: they were that poor couple who lost their kids.

I’m Gilbert and Adela’s great-grandson, one of their nearly 90 great-grandchildren they lived to see. Their story became one of letting hope overcome loss.

And their story, as so many do, starts with a visitor who changed everything. For us in 2020, the visitor, of course, is COVID-19, the pandemic that has killed more than 317,000 Americans, left so many of us alone and makes us wonder if life will ever feel normal again.

For Gilbert and Adela, it was a little girl. The daughter of their compadres, the girl had come to stay with my great-grandparents because her parents were having some problems, my Grandma Julia told me. The little girl was a bit older than their kids, Moses and Josefita, and grew attached to them.

The little girl returned home and died shortly thereafter. The Spanish Flu, my grandma told me. I didn’t know what that was, but I heard this story for the first time around the same time I was playing Oregon Trail, the seminal computer game, on my school’s one Macintosh computer. I pictured a little girl in a horse-drawn wagon for days, dying of dysentery.

Not long after her death, Grandma Adela had her kids playing under the tree outside of her adobe casita and heard Moses talking to someone. Moses told her he was talking to the little girl—that she wanted them to come play with her. It scared Adela. She told him not to say that. But sadly, too, both her kids soon would be gone.

On September 1, 1920, 11-month-old Josefita died of gastroenteritis with bronchial issues listed as a contributing factor on the death certificate I found this fall. Nearly three-year-old Moses died 11 days later. His death was attributed to pertussis.

God knew the family we would someday have, my grandma would say, but this little girl was all alone in heaven. My great-grandparents knew what it was like to be alone, both more or less orphans themselves. The little girl and their kids would never be alone. That’s how they made peace with it. Como Dios manda—what God commands.

In 2020, being alone is something so many of us have come to know all too well.

I sat alone in my studio apartment in Manhattan in March and April. I convinced myself I was doing OK. In May, when I decided to drive to Colorado to be with my family, I stopped in Chicago to stay with my good friends Sachin and Ann for the night. As Ann handed me a plate of food on the patio, I started to sob. The mere act of being cared for and spending time with friends cracked whatever survival shield I had built.

Months later, my mom in suburban Denver was also alone in the COVID ward of Good Samaritan Hospital, fighting for her life. I prayed each night that departed family members be sent to fill up her room since we couldn’t be there. I wanted them to be like the little girl in the tree—with one major difference, of course. On August 15, my mom was released from the hospital. This week we will celebrate her 70th birthday.

I thought about my great-grandparents a lot this year. They were people I hardly knew—my memories of them are somehow vague yet vibrant. And yet I feel like they’ve been emotional spirit guides through 2020, teaching me to be resilient and faithful through a pandemic.

We are all wondering what 2021 will hold. Will life resemble some version of normal as the vaccine works its way through the population?

In 2021, I hope they continue to guide me by teaching me how to move on with grace. It turns out I’m struggling with quite a bit of anxiety and worry that I’m going to let 2020 become a nasty scar.

I had COVID-19, too. It was a mild case, but the anxiety that has followed has been a struggle. For the first time in my life, I experienced insomnia. I checked my blood oxygen level maniacally for weeks, just in case. My mom sneezes and my head spins. I constantly worry about my dad, who seems to have all the risk factors, specifically being a Latino man in his 70s. I remind myself how lucky we are. My case was mild. My mom managed to get some of the best care available. Neither of us are showing signs of long-term symptoms so far. But I’m rattled. I’m sure you are, too.

In May 1921, Gilbert and Adela welcomed a new baby Julia, my grandmother. She was an only child for a handful of years. I imagine Granpo, as we called him, and Grandma needed a bit of time to heal—the 1920s version of #selfcare. They would go on to have six more children.

Aside from seeing it as God’s will, I don’t know much more about how they processed the loss of their first two kids. They are gone, my grandmother is gone and their only remaining child has dementia.

I don’t know if it made them fastidious and anxious parents. My mom says that by the time she learned about Moses and Josefita in the 1960s, her grandparents talked about it like a story, telling it as if they were disconnected from it. Perhaps they were. Or perhaps every time they looked among their sprawling family they thought, “They are not all here.” It was probably a bit of both, depending on the day.

But I do know that they managed to move forward.

They bounced around northern New Mexico and Denver before settling in the Five Points neighborhood of Denver in the 1940s. Their lives would be marked by highs and lows, like everyone else’s. They saw more births than deaths and came to be surrounded by a family that lifted them up. The couple who lost their babies had 18 great-great grandchildren when they died in the 1980s.

Domínnguez family reunion, 2015 (Photo by Evan Semon Photography)

That’s how I remember them: surrounded by family. I remember running my hands across my great-grandmother’s arm and her laughing at me and playing on her walker with my cousins. I can hear my Granpo, well into his 90s, playing his guitar and leading singalongs to De Colores or Cielito Lindo.

1920 was a horrible year for them, but it didn’t define them. Now for us, 100 years later, may we all say the same about 2020.

***

Robert Barba is an editor at The Wall Street Journal and is a longtime financial journalist. When there is not a pandemic, he lives in New York City. Twitter: @barbawire.