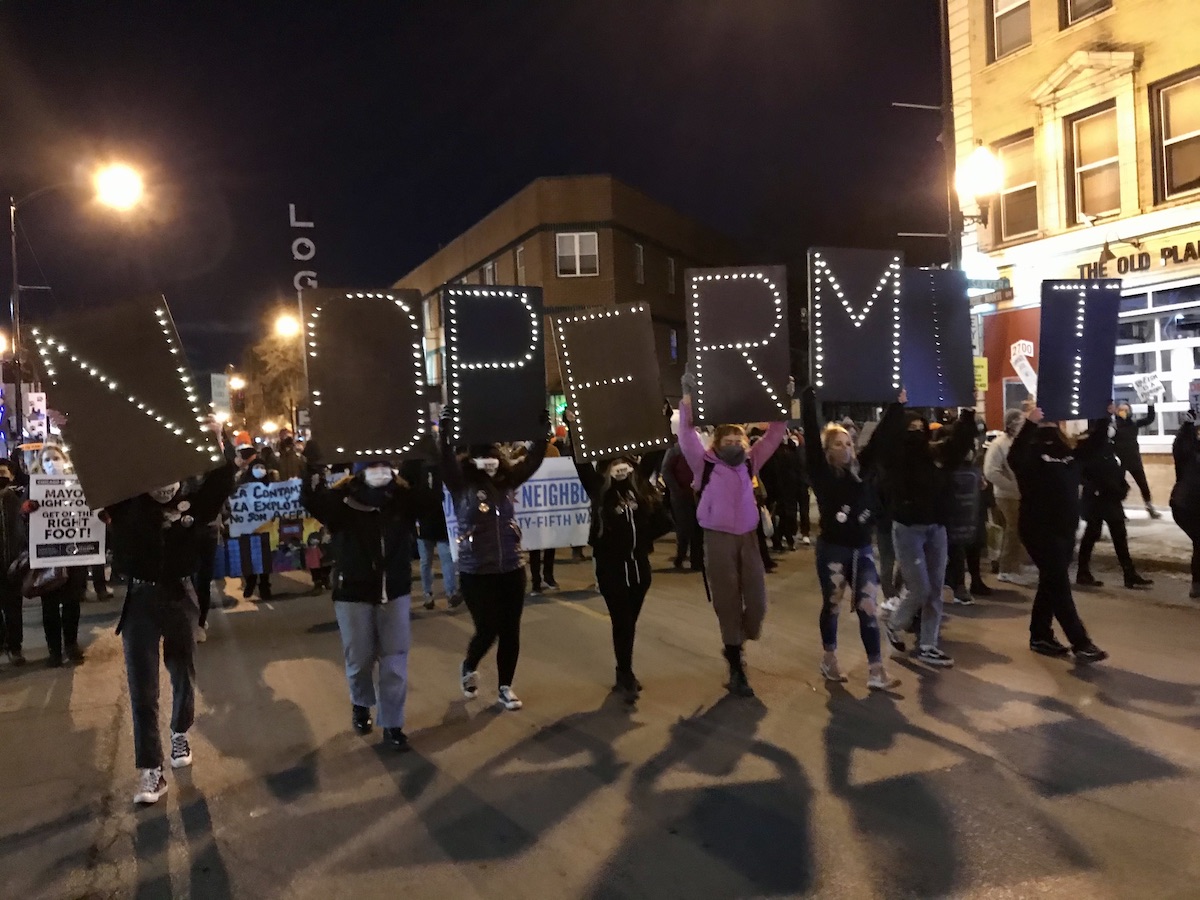

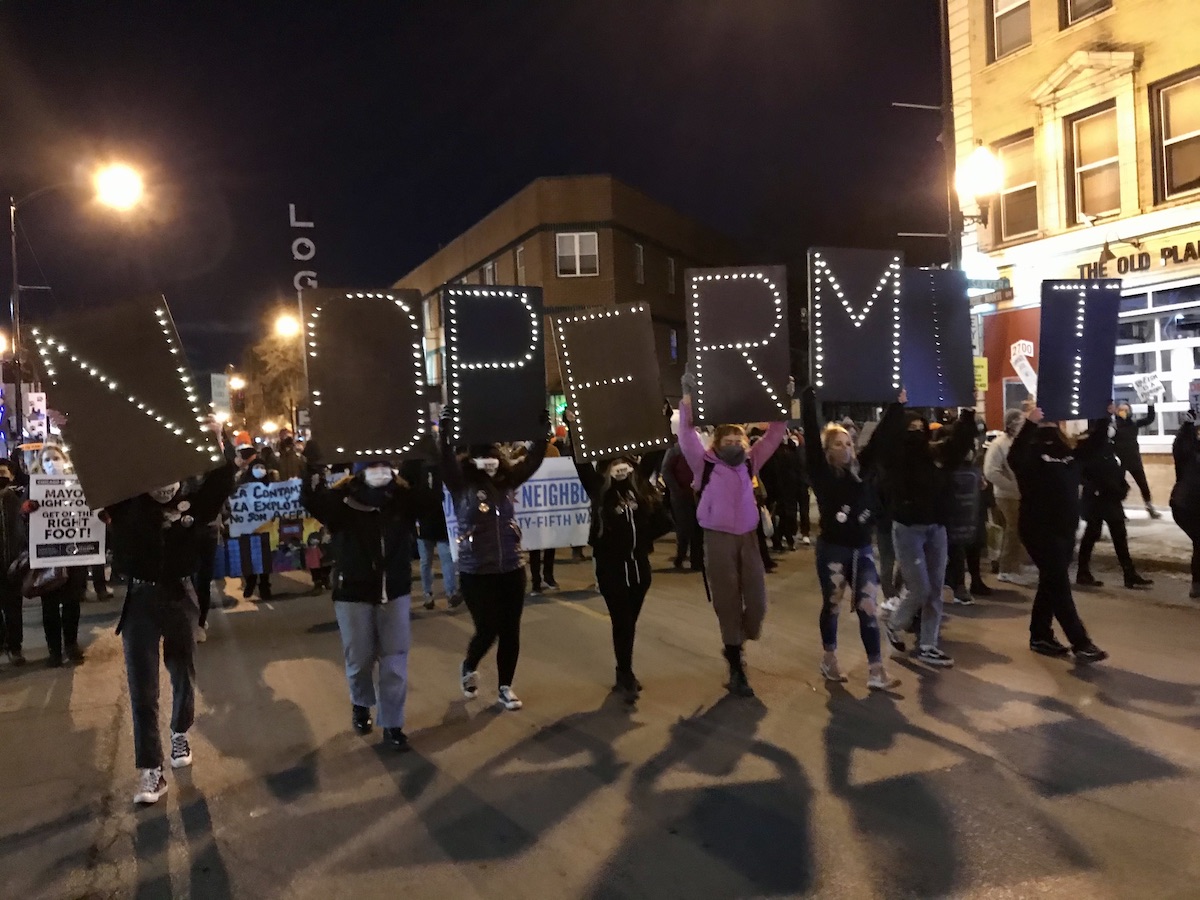

High school activists marched through the neighborhood of Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot on March 4, 2021 with big bright letters that read, “No Permit.” (Photo by Ariel Parrella-Aureli/Latino Rebels)

CHICAGO — For over a year, Latino activists from Chicago’s southeast side have been fighting to stop the planned opening of a metal-shredding facility in a community that already suffers from poor air quality and toxic waste.

The battle with the city is receiving nationwide support, including from healthcare workers, social justice groups, attorneys and Illinois legislators who hope to put increasing pressure on the mayor to deny the operating permit for the new Southside Recycling plant.

In an open letter sent Monday to Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Commissioner of the Chicago Department of Public Health, Dr. Allison Arwady, over 500 healthcare professionals and over 70 health care, social justice, urban planning and other groups asked the city to make a definitive decision that would deny the permit for Southside Recycling, which is owned by Reserve Management Group. The same company recently closed its north side facility, General Iron, earlier this year after a troubling history of pollution violations that the city settled for $18,000.

The letter of opposition to the plant comes amid an ongoing federal lawsuit alleging the city of environmental racism against Black and Latino communities, multiple protests and a month-long hunger strike staged by southeast side environmental justice activists that ended last week.

“We, the undersigned public health and healthcare workers and organizations urge you as City of Chicago decision-makers and as public health-, racial equity-, and health-equity-focused public servants to take decisive action to deny the permit to relocate the General Iron/Reserve Management Group (RMG) scrap metal recycling facility to the Southeast Side of Chicago and to support a broader environmental justice response to this situation,” the letter reads. “We stand in solidarity with the Chicago hunger strikers and their supporters who have been demanding environmental justice for the Southeast Side of Chicago.”

At a rally and march last week on Lightfoot’s northwest side block that announced the hunger strike’s end, activists said the fight for clean air in their community, which is home to mostly Latino and immigrant families, is far from over.

Dressed in black from head to toe, Óscar Sánchez and other activists hammered 30 nails into a large piece of wood that outlined his neighborhood map and read, “We deserve clean air.”

Southeast side activists made a fake wooden coffin and a neighborhood map that read, “We Deserve Clean Air” that was carried during the march. (Photo by Ariel Parrella-Aureli/Latino Rebels)

Each nail represented a day that the 23-year-old activist from the southeast side and three others went without solid food. Supporters from across the city, as well as nationally and internationally, joined in the hunger strike for a few days or weeks to show solidarity with the southeast side.

“We are environmentally burdened, and physically and emotionally traumatized,” Sánchez told the crowd. “We are here because we have been on a hunger strike for 30 days because Lori Lightfoot has not met our demand of denying the permit.”

Óscar Sánchez (center) last week in Chicago (Photo by Ariel Parrella-Aureli/Latino Rebels)

Standing in chilling 30-degree weather, organizers and local city officials addressed the crowd of over 200 supporters and then took to the neighborhood streets with a marching band and large signs in English and Spanish that read, “No permit,” and “Lucha contra la pobreza, no los pobres.” Sánchez and other youth activists who led the march carried a fake wooden coffin and chanted, “Lori Lightfoot, get on the right foot” among other phrases.

On March 4, 2021, over 200 supporters took to the northwest side neighborhood streets with a marching band and large signs in English and Spanish that read, “No permit,” and “Lucha contra la pobreza, no los pobres.” (Photo by Ariel Parrella-Aureli/Latino Rebels)

At a Thursday press conference held by hunger strike activists, attorneys, health care professionals and students who signed the open letter, speakers said the city needs to stand up for its Black and Latino residents already living in over-polluted areas and do right by them by denying the permit to stop what they call environmental racism.

“We are looking at a city that is intentionally allowing dangerous chemicals that will harm people and to do that intentionally is a serious problem,” said Damon Watson, an attorney with the NAACP who used to be a chemical officer in the U.S. Army. “The people have an opportunity to have an influence on what’s coming into their community. With protests, hunger strikes, lawsuits going to the federal court, what more [does the] city need [to see] the people do not approve of this?”

Although Southside Recycling owners argue the new facility —which stands a block away from a high school— will provide essential services with a cleaner, more environmentally responsible shredding process and is not the same as General Iron, activists say the company should still not be allowed to operate in the area, which has been overburdened with pollution and particulate matter for decades, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. Since 2014, more than 75 companies in the area were investigated for failing to meet the Clean Air Act compliance in cooperation with Illinois EPA and the City of Chicago’s Department of Public Health.

Particulate matter, like dust and solid particles in the air, is known to increase the risk of cancer and asthma rates, which are high in the southeast side. Oil byproducts, like lead, arsenic and manganese, have also been found in the area.

The City’s 2020 health and air quality report found that although city pollutants have decreased by 40% since 2000, concentrations are still among the highest in the nation. The report also indicated that south and west sides of the city, home to more Black and Brown families, are still overburdened with unhealthy air and are more vulnerable to the effects of air pollution compared to northside residents.

Environmental experts said Thursday that the city’s air quality report is proof that Southside Recycling should not be allowed to operate, especially looking at the company’s track record that violated city, state and federal rules from the EPA.

“The city has a duty to comply with civil rights laws and cannot favor more affluent, white areas over the expense of lower-income residents,” said Nancy Leob, the attorney representing local environmental justice groups in the federal lawsuit and the director of the Environmental Advocacy Center at Northwestern University.

Yesenia Chávez, a lifelong southeast side native and the daughter of Mexican immigrants, participated in the hunger strike for 25 days. When she started, she weighed 134 pounds; now, she weighs 117. She said the strike not only physically affected her but also was strenuous emotionally and mentally. But it was important to shed light on the issue facing her community, particularly for residents living in more white, affluent Chicago neighborhoods, she said.

“The fight to continue will be just as strong as when we first started [the hunger strike] and we will keep working toward better representation politically for Latinos of the city who have endured loads of environmental contaminants,” Chávez said in Spanish at last week’s rally.

Yesenia Chávez, a lifelong southeast side native and the daughter of Mexican immigrants, participated in the hunger strike for 25 days. Speaking at a rally last week near the mayor’s house, she asked all of the women activists to stand with her in honor of Women’s History Month. (Photo by Ariel Parrella-Aureli/Latino Rebels)

In a letter sent to hunger strikers last month, Lightfoot said she wants to work with community members to address concerns about pollution and health but did not agree to deny the permit, according to the Chicago Sun-Times.

At last week’s rally, activists called on the mayor to have a personal conversation with them about their concerns and to commit to putting Black and Brown communities before corporate industries.

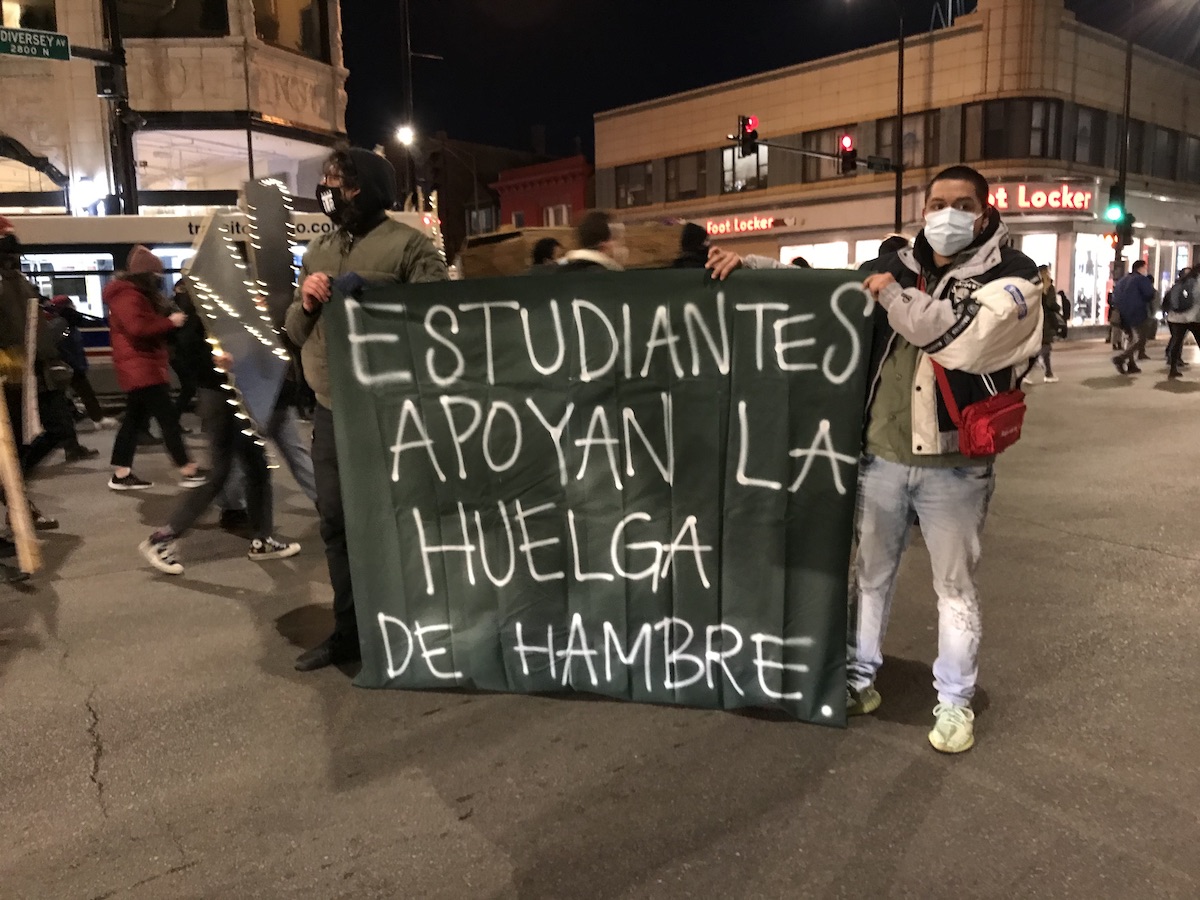

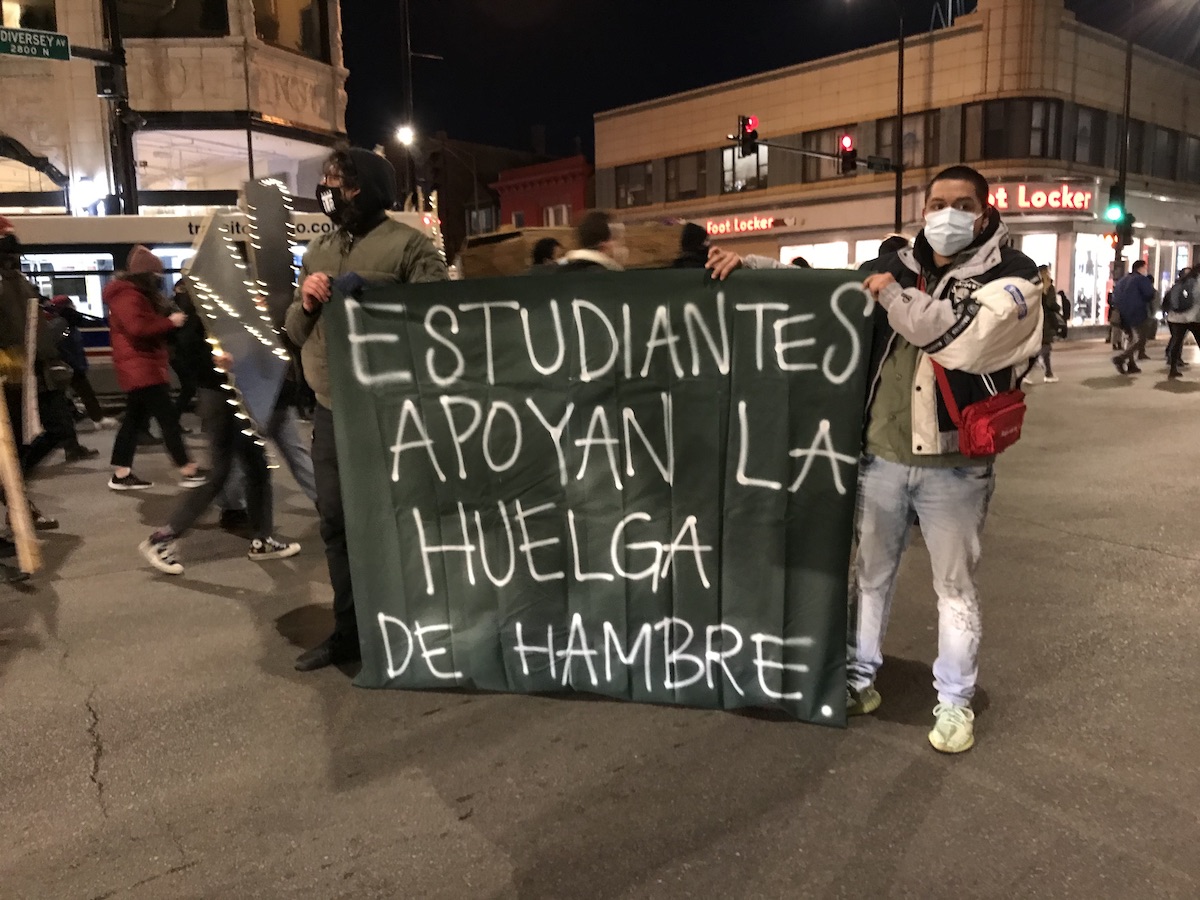

High schools activists hold a banner supporting hunger strikers during a rally through the neighborhood of Chicago Mayor Lori Lightfoot on March 4, 2021. (Photo by Ariel Parrella-Aureli/Latino Rebels)

In a statement to Latino Rebels, the Mayor’s Office said Lightfoot will continue community engagement to address residents’ concerns but did not say if she has plans to meet with the activists directly, as they are requesting.

“Our efforts to create a more environmentally just and responsive city is about more than one facility—it is about advancing policies that truly promote the health and well-being of people who live near industrial areas,” the statement reads. “The City will continue to work to address residents’ concerns, both for RMG/Southside Recycling and on these broader policy issues.”

As the city faces mounting pressure to deny the permit, activists hope the increasing support nationwide and the open letter, as well as the federal lawsuit that could see a decision as early as next month, will bring an end to the metal scrapper’s opening. In addition to the federal investigation, activists are calling on President Biden to speak out against RMG’s new metal plant and want progressive Latina members of Congress, like Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, to help get the city to deny the permit.

***