By Pablo Alvarado and Nadia Marín

Versión en español aquí.

Thirteen months ago, as a new virus emerged and spread fear across the nation, a new term also appeared: “essential worker.” The term was coined by the Department of Homeland Security, an agency that had been trying to terrorize immigrant workers into leaving the country. But the term took hold more broadly, and from one day to the next, the idea of essential workers became part of our shared vocabulary as we collectively tried to make sense of these terrifying and uncertain times.

While the rest of us took shelter in our homes, essential workers went out each day to protect the community’s health and well-being. They took the risks that enabled the rest of us to live in comfort and safety. They received praise and gratitude. They were the subject of political speeches and soundbites. They even received applause from celebrities on social media.

Of course, all workers whose families depend on them are essential. And all work is essential for those who need income to survive. And the jobs “essential workers” perform have always been essential. It was only in the harsh light of the pandemic that we understood, briefly, how much we needed them and how truly unfair —and even unjust— our reliance on them was.

The virus has challenged the proposition that in this country, all workers —all people— are created equal. It was a test that we failed as a society. We did not always protect the ones who faced the greatest danger of sickness to keep the rest of us safe. We did not protect the vulnerable. We were unable to keep our elders safe.

“Essential workers” have died by the tens of thousands over the last year, at far greater rates than others. We all know this, but as the praise from politicians and on social media has subsided, not enough people are talking about it. And almost no one is doing anything about it. Black and Brown workers, who make up a disproportionate number of “essential workers,” have also died disproportionately. In Los Angeles, where 23,000 people have died of the virus, COVID-19 has killed Latino residents at a rate nearly three times that of white residents.

So much of this sickness and suffering is unjust, and it reflects a sickness in our law and politics, particularly when it comes to immigrants. Just turn on FOX NEWS to see how sick our society has become. White nationalists invent phantom threats and blame President Biden for a human rights crisis that they themselves created along the border while ignoring a real domestic crisis of staggering proportions wherein immigrant families have been condemned to work often to their death for a nation that deprives them of basic rights. To repair what is wrong, much must be done, but we can start by seeking some semblance of justice for the families the fallen workers left behind.

First, we must honor the dead.

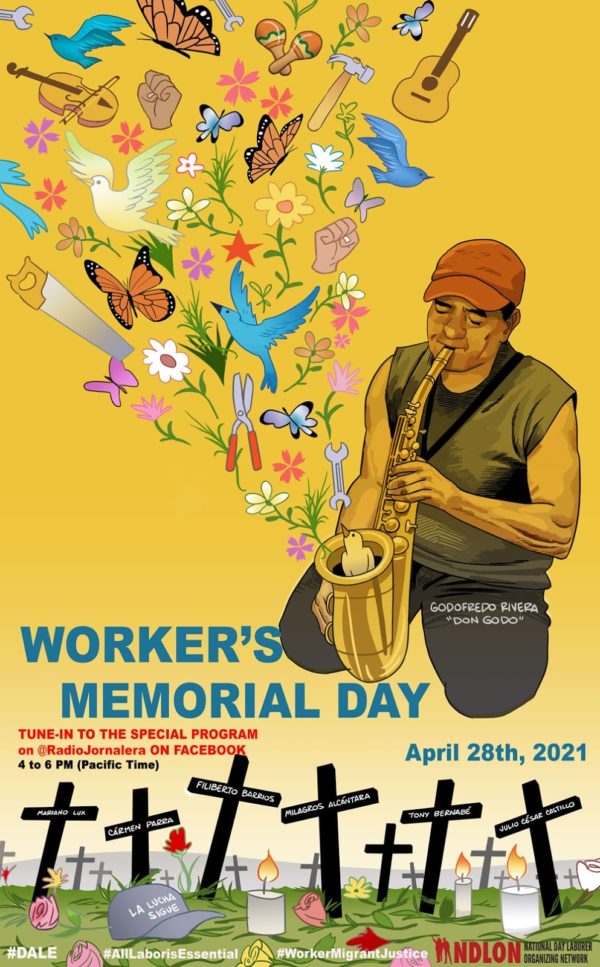

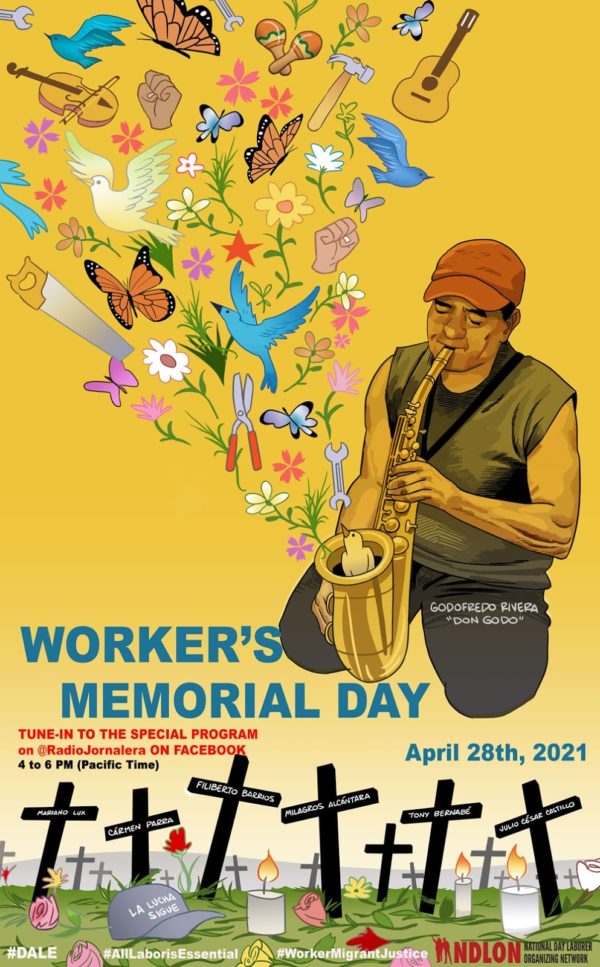

On Wednesday, April 28, in Pasadena, we will pause to remember. Six hundred wooden crosses placed in the grass at Villa Parke will form the memorial, a symbolic final resting place to bring together those who are gone with those who are grieving. The crosses, made of simple pine, will each be marked with a name, date of birth and death, and occupation of someone who died in the pandemic.

The cross is the symbol of ultimate sacrifice, of suffering and death endured so that others may live. The rows of crosses will resemble a military cemetery, to evoke the vast scale of the loss and to also make an important connection. Fallen soldiers are among our society’s most honored dead. We respect and remember their sacrifices that keep our society intact. Fallen immigrant workers are no different. We must no longer ignore and dismiss them.

Who were these brave women and men?

Here are a few: Gil Espinosa, a warehouse worker, age 44. Alfredo Manríquez, a gardener, age 54. Mónico Manríquez, a gardener, age 83. José Antonio Bernabe Lule, age 61, a day laborer, organizer and immigrant-rights leader. Garment workers Antonio Macías, 63, Enrique García, 34, and Filiberto De la Cruz, 62. Day laborers Marina Villanueva, 60, Francisco Delgado López, 98. Godofredo Rivera Hernández, 70, a day laborer, dry-cleaner worker and musician. Policarpo Chaj, age 49, a Mayan K’iche leader, organizer and court interpreter.

These people and others lived and worked in cities and towns and suburbs in all the states. They worked in the meat-packing plants, who were forced to stand too close to their colleagues on processing lines without enough protection from the invisible virus. They worked in restaurants, cooking meals, washing dishes, mopping floors, and cleaning toilets at risk from the virus for many hours each day. They worked in fields, planting, caring for, and harvesting food that every single one of us consumes. They earned their livings making deliveries and cleaning homes, caring for children and the elderly, the fragile and the sick. Then they got sick themselves.

So many of these people were once migrants who crossed a border into this country to begin new lives of strenuous work and sacrifice in hopes of taking part in a shared national dream of prosperity, progress, and infinite possibility. Hope brought them here, and hope sustained them through long days and years of toil that was difficult and often dangerous. They held on to hope, once this country’s most precious shared national resource, just as they held on to dignity, as do all laborers who use their hands and hearts in service to others.

When the coronavirus came, walls of protection were swiftly raised, and those who could protect themselves carried on with their lives at a safe distance, using the virtual shields of their computers and phones.

While others, though they knew it could be deadly, kept working out in the world. It had to be done. What choice was there? They knew the horrible calculation, the terrifying decision: To survive, you must go to work. To feed your family, you must risk your life. Side by side in the factory and restaurant kitchen. Using old and dirty masks, or no masks. Gloves or no gloves. Doctor or no doctor. Strong or frail, with underlying health problems like diabetes or high blood pressure.

The virus threatened all of us but not equally. In shameful numbers, these workers got sick. Many died at home. Many died at the hospital. Some avoided help until it was too late, afraid to risk arrest and deportation. Some died because, without the right identification papers, they could not get life-saving help.

They could try to be safe, or they could go to work. They could not do both. So they worked, day and night, exposing themselves to the virus that found them and then suffocated and killed them. As we all know, COVID death can be a horrible one. It can leave you alone with no family members to hold you, no bedside circle of love to surround you as you leave. How horrible, too, to die with no way to return home, to be buried in the land of your birth, near the home you abandoned out of love when you traveled to this country to provide for your family.

In a just and honest nation, one that recognized service and sacrifice, these people would be placed among our greatest heroes, alongside fallen soldiers, firefighters, and first responders. We expect nothing less for the women and men whom we honor this month. We will not allow these precious souls to be scattered like dry leaves, to be known by no name except by the hollow term, essential worker.

Therefore, we propose this. An immediate amnesty for the surviving immigrant family members of those who perished while their work was deemed essential but illegal. Those who have died as undocumented workers —those who, outrageously, were given government papers only in the form of a death certificate after they stopped breathing— cannot benefit from authorized status. So let us give it to their sons and daughters, brothers and sisters, husbands and wives, who continue to make up part of our national family. Anything less would enshrine a moral failure, a form of moral death for a country that once told itself a story that the source of its strength came from the people who arrived and built a better future here.

We owe amnesty at this point. It is a debt that has come due.

In Pasadena, we are starting by etching into crosses the names of 600 souls who have crossed into a new existence, lost to us for now but alive in our memories and hearts. Now the job falls on us, the living, to name and honor the dead, and in the process, to defend and honor the spirit of a nation that once prided itself on being a refuge for those who wanted to share in the reward —not punishment— of hard work. We owe it to their families, and we owe it to our collective family, to properly grieve during this shameful juncture of history and to allow our mourning to give way to a new chapter of renewed hope for a return to shared national values.

***

Pablo Alvarado and Nadia Marín are the co-executive directors of NDLON, the National Day Laborer Organizing Network.

[…] abusive work environments. Moreover, we have called upon the Biden Administration to provide an immediate amnesty to all surviving family members of undocumented immigrants who died because of performing essential labor during the […]