Migrant workers carefully choose and cutoff yellow squash at Kirby Farms in Mechanicsville, Virginia. (U.S. Department of Agriculture/Creative Commons)

This article was first published on Medium

Immigration reform, not mere temporary work permits, is overdue and needed for those living in the shadows while working in this country as undocumented. It’s essential for day-to-day living free of fear and with dignity. It is also urgently needed as a long-term solution to labor shortages amid a supply-chain crisis, and for workers in agriculture, construction, factory work, and other high-risk work to not only have access to basic work safety conditions, protections, basic health coverage, and fair pay, but also have a path to legal residency.

The last time the U.S. approved any form of immigrant relief was nearly 36 years ago —the Immigration Reform and Control Act signed by President Reagan in November 1986— and that reform was meant for Latinos who met specific requirements. It’s time to reconsider this lengthy pause that has affected and upended the lives of many including those whose visas have expired and who cannot return home nor apply to readjust their visa status due to immigration laws and loopholes.

Undocumented Essential Workers and Labor Shortage

Undocumented migrant workers supported the U.S. amidst a labor shortage during World War ll via the Bracero program, which allowed in hundreds of thousands of manual laborers every year from Mexico between 1942 and 1964.

“The year with the highest level of bracero importation is believed to be 1957, when more than 192,000 workers were brought to California, and more than 150,000 other workers to other parts of the country,” according to an article on the Oakland Museum of California’s website. “Major growers of the Southwest strongly favored the continuation of the program because the imported workers could be brought in when they were needed and made to leave when they were not. But it was apparent to anyone who cared to look that the program produced something far less than optimum for migrant workers—extremely low wages and dreadful working and living conditions.”

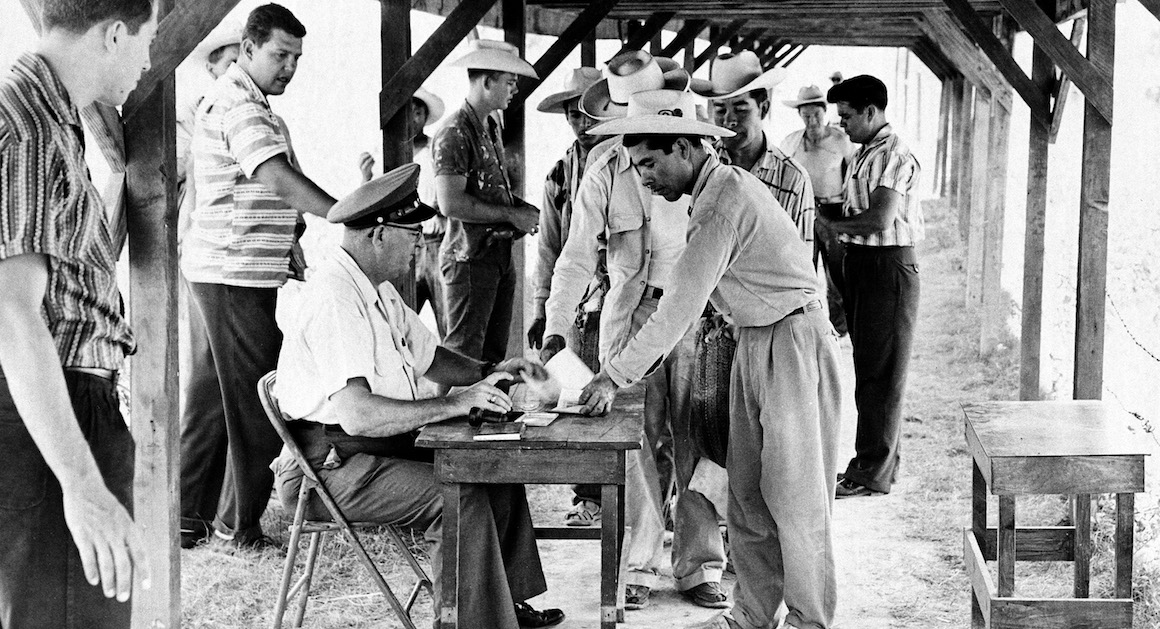

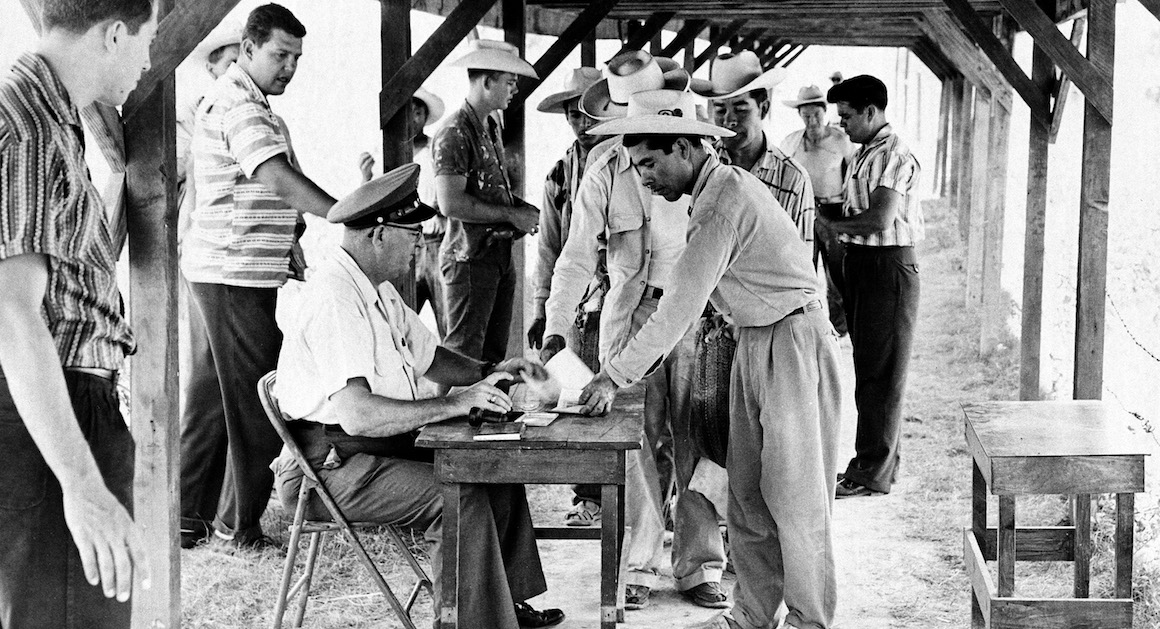

Mexican farmworkers are shown being processed at the labor center in Hidalgo, Texas, June 18, 1959. Most of these workers, who were legally employed under the Bracero program and protected by minimum wage law, stayed in Texas, but some traveled as far as Michigan to work. (AP Photo/USCIS)

Undocumented migrant labor continues to support the U.S. to this day, more visible during the current COVID pandemic where essential workers, many of them undocumented, aren’t paid nearly enough for risking their lives on a daily basis.

Congress should enact full immigration reform not only for essential workers like those in agriculture and the medical field, but also those in construction, the food industry, and more, all of whom are crucial in sustaining and even strengthening the nation’s economy. This makes immigration reform not only the right thing to do, but the practical, smart thing to do.

Why Immigration Reform Matters to Me

Immigration reform is important to me not only as an advocate for victims and survivors of violence, undocumented migrant workers, and refugee rights, but also because I have family and friends who continue to live in the shadows, waiting in limbo as I once did.

The author, second from right, lobbying for juvenile justice reform as a member of the Peace Alliance, Washington, D.C., 2014 (Courtesy of Gia Santos)

They are all essential workers. Some are students caring for patients during the pandemic, not knowing if DACA, which protects from deportation those undocumented people brought to the States as children, will even continue as they study and contribute to this country. Many work in the construction industry during extreme cold in the winter and extreme heat during the summer, designing and leading large-scale projects that have built schools, a stadium, churches, synagogues, and more in the state of Texas alone, all while being underpaid with no benefits and no health insurance to cover sickness or injury. Others work in the food industry, cooking the most delicious cuisine —not only Mexican but any and all cuisines— which has fed a hungry nation during a seemingly endless pandemic, with no health insurance themselves.

Immigration Reform and the Visa Backlog

While the right may argue that only legal immigrants matter, I give you the following personal examples.

It was 2019. I was in Seattle, Washington visiting Mom when she had a nearly fatal brain aneurysm. Some family members in Texas couldn’t visit us at the hospital due to their legal status, though my grandparents and a cousin of mine were able to vitist twice to be near Mom and offer support during a difficult time.

During that time my mom’s brother from Mexico had applied for a humanitarian visa to visit her but was denied. His son was also denied when he applied for a humanitarian visa to attend the funeral of my cousin Frank, who was murdered during the pandemic in 2020.

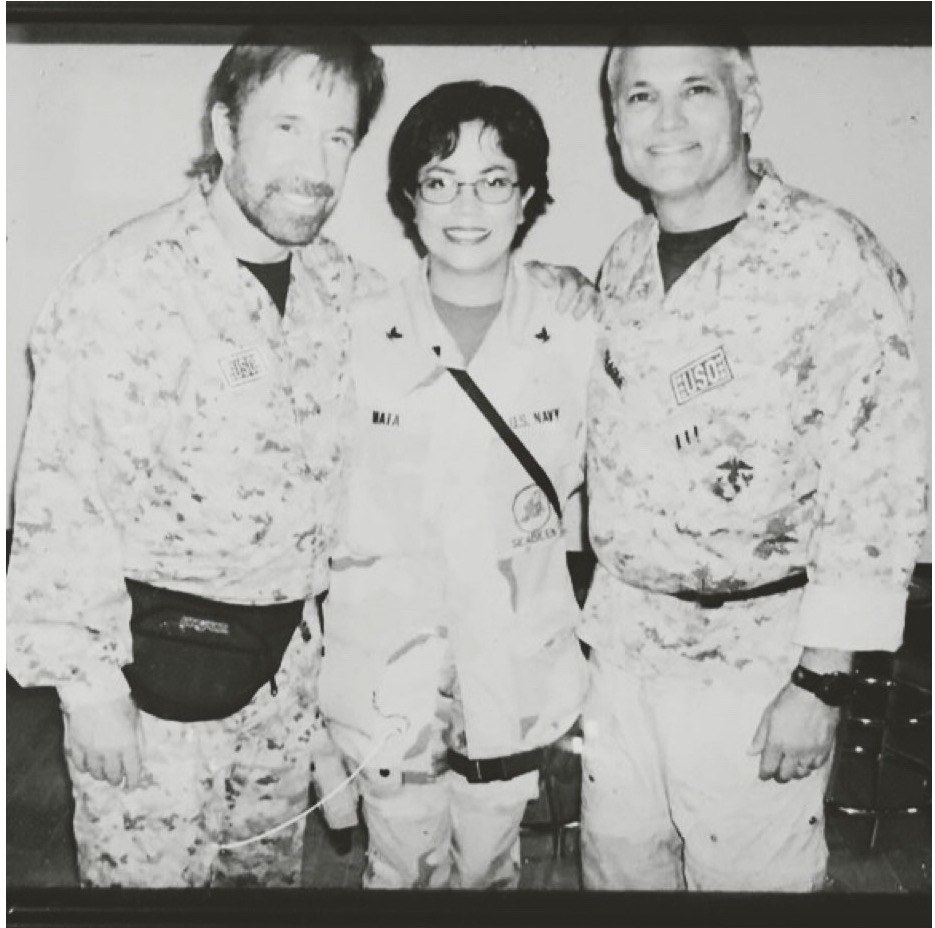

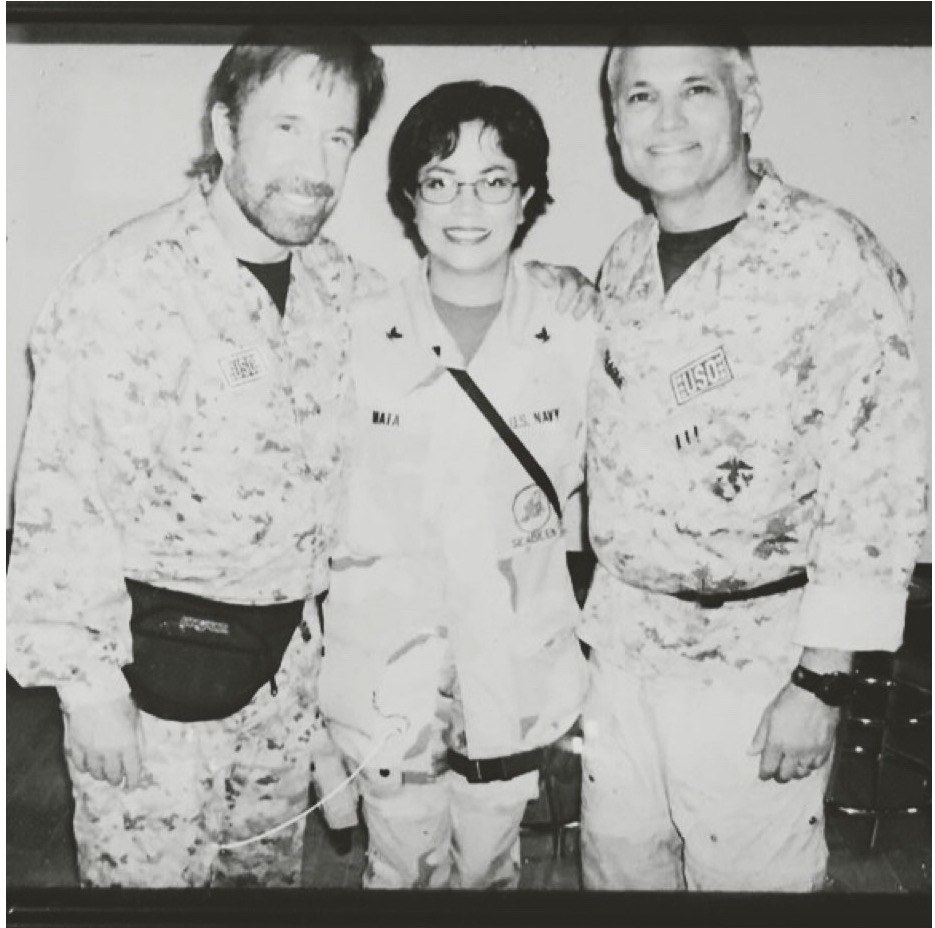

The author’s mother Sylvia with Chuck Norris, left, during her deployment in Iraq (Courtesy of Gia Santos)

The hours spent researching, applying for a visa or a special work permit for a cousin who finished university with a degree in legal studies, and for another cousin who has a master’s degree in business, only to be told by immigration attorneys and U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) that there was no way to apply unless a large corporation invited them or if they applied through a direct family member. You’re looking at a 10 to 15-year wait according to USCIS and other immigration sources.

This is part of what is wrong with the immigration system as a whole, and why immigration reform encompasses the need not only for those who are already living and working in the country while undocumented. It also includes those with expired visas and those who apply outside the country for student-work visas, as well as those who desperately need humanitarian visas. Instead, politicians, ambassadors, and the wealthy receive special treatment for their families whose visa applications are processed promptly and rarely denied.

My Experience as a Survivor of Domestic Violence While Undocumented

The term “living in the shadows” is something I’m familiar with. I grew up waiting for some type of legal path that would allow me to become a legal resident. I did so while surviving a relationship that soon involved domestic violence, from the early 2000s as a teen through my early young adult years, and it was only after I escaped Texas with my kids to California —with support from Mom, who at the time had recently returned from deployment in Iraq— that I finally received my legal residency.

The author, right, as a young girl, early ’90s (Courtesy of Gia Santos)

By that time, however, I had untreated mental health issues related to the trauma I had suffered, which made it very difficult to adjust to a new life as a documented person. I’m not the only one who has lived under such circumstances, nor sadly will I be the last.

I shared part of my story some years ago for the Pixel Project, which seeks to end violence against women by raising awareness and funds. I have never shared how I went through all of that while being undocumented and waiting in limbo for my case to be approved for years, until now.

I believe it’s important for members of Congress to enact immigration reform for the millions who live in the shadows, especially for the women and children who are often left with no option but to continue living in the shadows, trying to survive day to day, while hoping for freedom and security in the land of the free.

Statistics for Undocumented Women and Domestic Violence

The National Coalition Against Domestic Violence estimates that only 34 percent of people who are injured by intimate partners receive medical care for their injuries. This doesn’t account for those who are undocumented and afraid to seek some form of help, especially from police or at a clinic or hospital, where they may be forced to provide documentation and thus reveal their undocumented status. Many are also threatened with deportation, as I was at one point, as a means of control.

Furthermore, “Abuse rates among immigrant women are as high as 49.8%,” according to the National Organization for Women. “Besides physical, sexual and emotional abuse, partners may also use women’s immigration status as a weapon, threatening them with deportation, or refusing to file immigration papers for them, or to continue sponsoring them,” writes Francisco Castro, a fellow at the Center for Health Journalism.

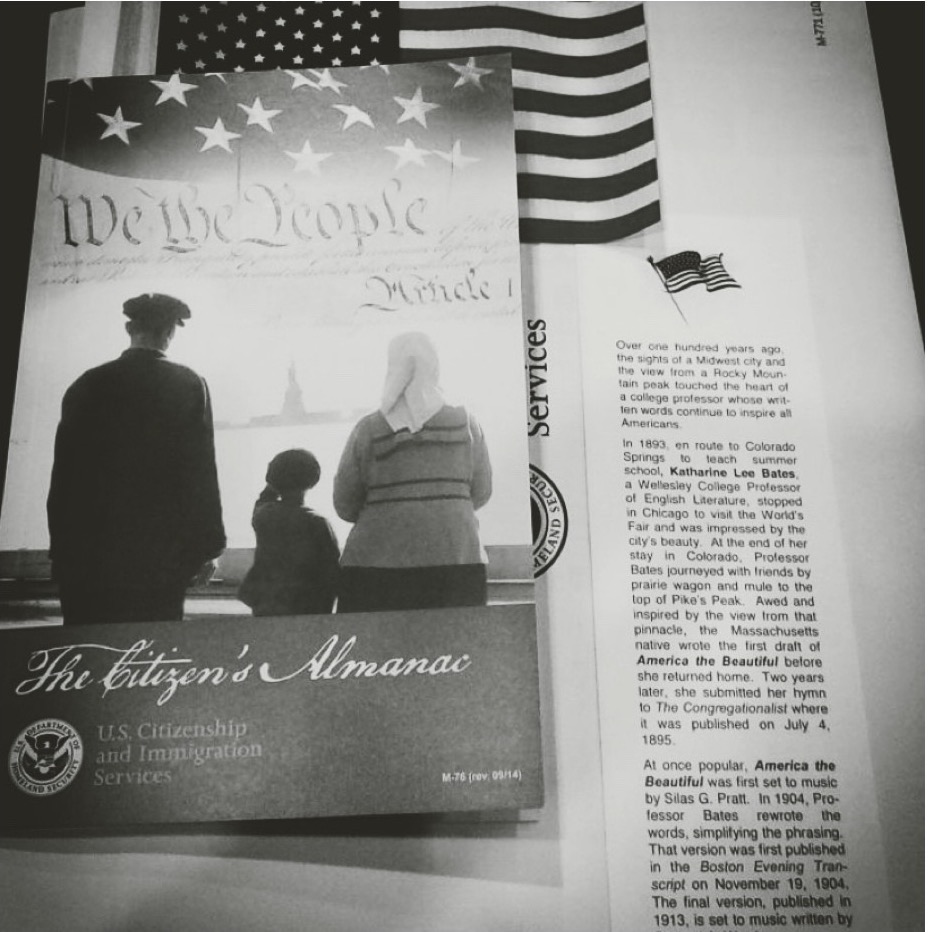

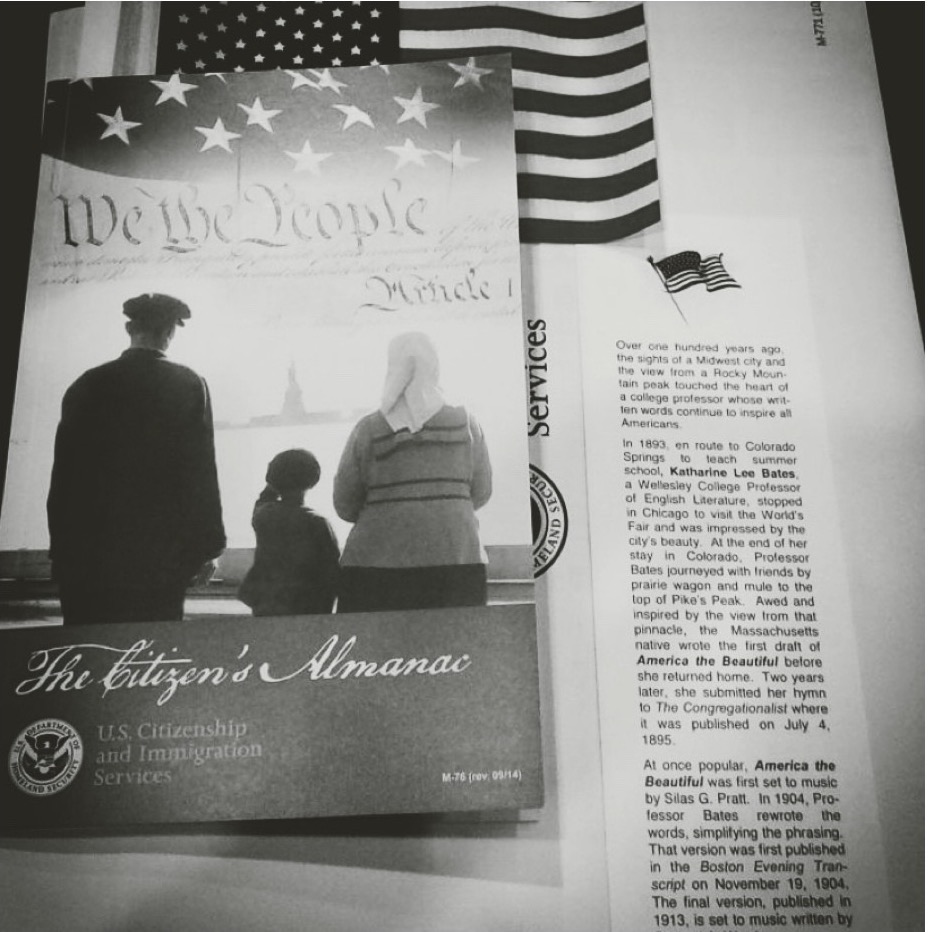

From the author’s citizenship ceremony in San Diego, California, 2016 (Courtesy of Gia Santos)

Will We See Real Reform This Year?

With each session of Congress and each new administration, the issue of immigration reform is almost always utilized for political gain, sprinkled with too-good-to-be-true promises only to be tossed aside altogether right before or during an immigration vote. While immigration reform is a topic included in the Build Back Better Act, this administration’s next moves will very likely dictate whether or not it remains in power following the 2024 election.

It is in President Biden and his party’s power to work with Republicans and change the narrative of undocumented immigration, for the betterment of this country.

***

Gia Santos is a bilingual writer and editor, and an advocate for immigrant rights and victims of violence. She is the co-founder of Artists4Freedom. Twitter: @Gia_Santos_

[…] vagas por ano fiscal para 88 mil; pouco, se comparado aos cerca de 700 mil detidos na fronteira. As soluções de longo prazo estão sendo deixadas de lado através de medidas como essa, que privil…, sem garantia de equipamentos de proteção individual, assistência social, plano de saúde, […]