After they filed a complaint with the Ministry of the Environment in 2018, which was unsuccessful, a judge ordered the seizure of the farm owned by Moisés Montero and his wife Neila. (Tova Katzman/CPI)

By Errol Caballero, Centro de Periodismo Investigativo and Concolón

The farmer looks down from the top of the slope. The dark-skinned and bulky man is dressed in gray overalls and a wide-brimmed hat. This is part of the gear used in pineapple crops that is meant to protect him when applying pesticides and other hazardous products.

At the foot of the slope lies Isadora Rojas’ house. Pineapple crowns peek out from the opposite plot. Like many farmworkers, she wears jeans and a long-sleeved checkered shirt. Standing in front of the half-finished chalet entrance and stepping on the ground still soggy from the recent downpour, she remembers the smell that warns her when they fumigate the plantation. When she notices it, she rushes to close the doors. But the chemical that is coming down from above ends up flooding La Esperanza Street where she lives with her three children: Cristian, Miguel, and Alexis.

The family lives in the agricultural area of the La Chorrera district, where the government of Panama has allowed the use of chemicals that are harmful to health and are prohibited in 32 countries. The chemicals are affecting the water resources that supply more than half of the country’s population. Panama not only imports and uses these chemicals in its fields, but also produces and exports them to other countries, taking an active role in a multimillion-dollar and questionable global market.

For the Rojas family, there is no escape: they live in a low area, between two hills. The chemical seeps into the room where Cristian, 23, is lying against a wall decorated with colorful children’s drawings. A disability keeps him in bed. Isadora has taken him to Panama City, more than 41 miles away, to have his lungs checked, which are not working well. Outside, you can hear the howl of the geese over the sound of “The cricket” —the tractor whose sprinklers resemble the wings of these insects— passing between the hills.

“How am I going to get away if the poison is so close? Where are we going to go? I can’t carry my son up there,” she asks, reliving the anguish.

Her family is one of 10 affected on that street —consisting of just two strips of asphalt, divided by a strip of dirt and boulders— that ends at the main entrance of Colorada Fresh Pineapple. It is about 40 hectares with hills colored by crops on the slope, with a small lake formed by a dammed creek and some houses around it. Pineapples are grown here to be exported to Europe and Asia, where several countries have banned agrochemicals that Panama has approved for restricted use. Every week 13,000 pounds are shipped by boat and plane.

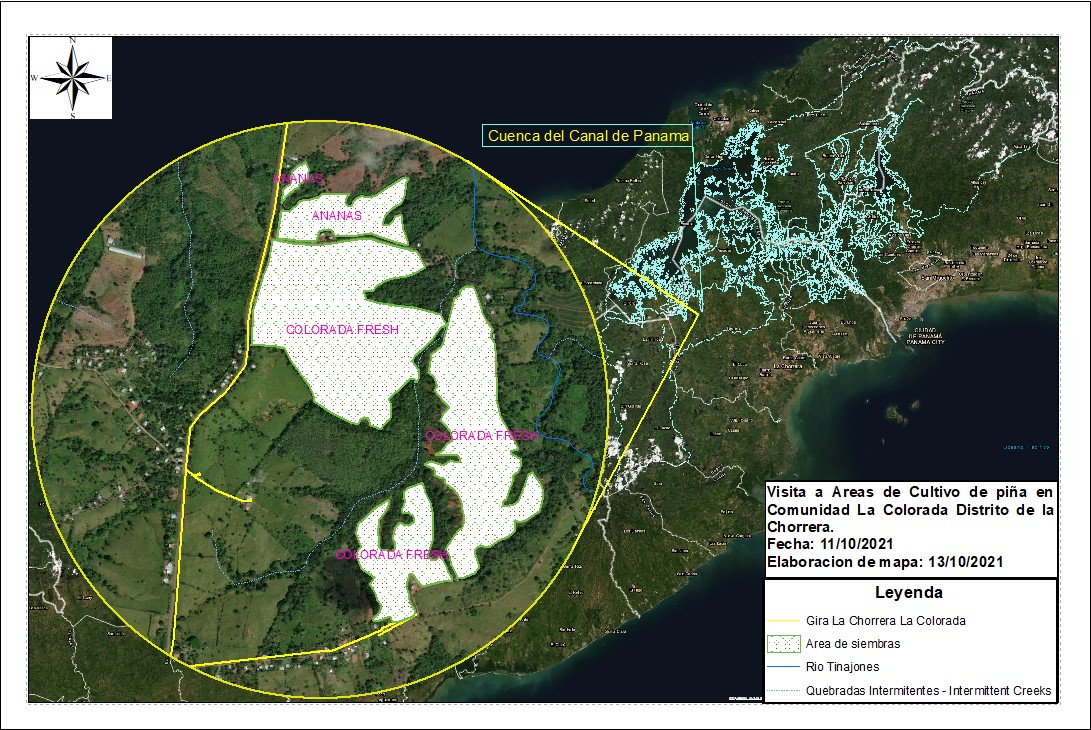

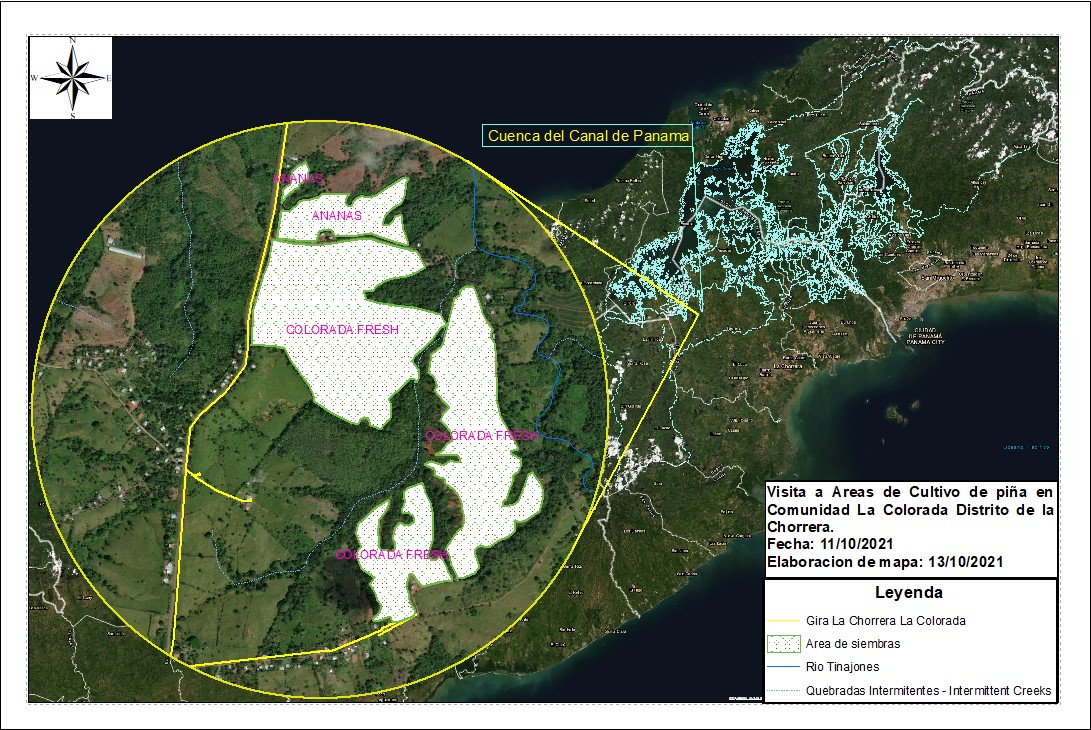

La Colorada is one of the communities in the Iturralde district, with an estimated population of 1,721, according to the National Institute of Statistics and Census. It is part of the district of La Chorrera, in Panama Oeste, a province where 80 percent of the country’s pineapple production is located.

From the Hills to the European Markets

Deep in the plantation, in La Colorada, Las Yayas or Cerro Cama, or La Chorrera’s urban center, the provincial capital, pick-ups drive by crammed with pineapples. Their yellow color shines like golden nuggets amid the dull green of the crowns.

It’s Pineapple Country—so says the promotion used by Colorada Fresh Pineapple to attract investors online, although in the last six years the land allocated to cultivation and the number of producers has decreased. Exports generated $7.5 million in 2020, the lowest figure in seven years, a drop of $36.6 million compared to 2013. Even so, last year the Ministry of Commerce and Industries of Panama (MICI) registered an increase in production: 667 hundredweight more than in 2020.

In 2001, a study by the Bolsa Nacional de Productos S.A. estimated the amount of pineapple exported by Panama at 70 metric tons per year, at an approximate cost of $15.43 per box. Today, the price of a box varies depending on the transport used: if shipped, it costs between $5 and $6, while an average box weighing 26 pounds sent by air costs between $10 and $12 in the European market.

Colorada Fresh Pineapple grows the MD2 Golden variety, introduced by the multinational Del Monte in the 1990s. Recognized for its sweet flavor, low acidity, and its high content of vitamin C, it is part of the 75 percent of the pineapple production that is destined abroad. Its main clients are in Europe —Holland and Italy— and in the Middle East.

In a promotional video, Colorada Fresh Pineapple’s CEO James Gooden, a Texas attorney with experience working on oil rigs and in the real estate business, brags about the 15,000 fruit they grow per week on its farm located in the heart of a community where in recent years the land dedicated to cattle grazing has been converted into plots dedicated to commercial agriculture.

That production volume is necessary to balance out the investment of the agricultural companies. About 50 percent of the investment in pineapple production is destined to buy raw materials and for irrigation work, according to MICI data.

The demand for MD2 in the international market has led those who grow it to increase sowing density —the number of plants per hectare— and to opt for procedures that facilitate agricultural work, such as planting in favor of the slope, a practice that promotes soil erosion.

The erosion has affected the streams and water wells, according to the testimonies of neighbors such as Moisés Montero and Antonino Valdéz, and an inspection by the regional directorate of the Ministry of the Environment (MiAmbiente) of the government of Panama early last year.

After they filed a complaint with the Ministry of the Environment in 2018, which was unsuccessful, a judge ordered the seizure of the farm owned by Moisés Montero and his wife Neila. Now he drives for Uber. (Tova Katzman/CPI)

On May 26, 2021, the director of the Panama Oeste province, Marisol Ayola, ordered an administrative process against Inversiones JPW SA for “launching activities without an environmental impact study and damage to a water source, by building a dam without the corresponding permits.” The firm is a public corporation that manages the operation of the pineapple farm that Gooden has presided over since 2019. The environmental authorities called for the end of farming activities there, but the neighbors have seen that they have continued.

The MiAmbiente resolution also says that Colorada Fresh Pineapple operates without an environmental impact study, as environmental officials confirmed in the January 2021 inspection. This, even though Article 7 of Act 41 of 1998 establishes that projects or activities that may generate risk for the environment must have “an environmental impact study prior to its start.”

A list of questions was sent to MiAmbiente to learn the company’s standing regarding the required environmental impact study, but the agency did not respond. The MiAmbiente online registry was searched, but no environmental impact study could be found for Inversiones JPW Panamá or for Piñas del Oeste, S.A., which sold the plantation JPW in 2017.

The current president of the latter company is Lucas Alemán Healy, member of a renowned family of lawyers and the director of Codere, a multinational that is the concessionaire of the Presidente Remón Racetrack in Panama City.

The National Impact on Water

The heads of Inversiones JPW S.A. did not comply either with MiAmbiente’s instructions to eliminate the dam which they use to store water in a small lake to be used during the dry season. The inspectors reported that the channel shows a “drag of sediments and leachates, which reach the creek” from the slopes that are used for crops. A leachate is a residual liquid, generally toxic.

The creek is a tributary of the Los Tinajones River, which in turn joins with Los Hules before flowing into Gatun Lake, which feeds the Canal and eight water treatment plants that supply the provinces of Panama, Panama Oeste, and Colón. These rivers, along with the Quebrado channel, make up a sub-basin that is part of the waterway’s water catchment area.

Photo courtesy of Alianza para la Conservación y el Desarrollo

It’s a situation that affects a national strategic resource: the Canal and approximately 55 percent of the population depends on the basin’s water.

Downriver, in La Colorada, one day Moisés Montero found 60 dead chickens. He attributes it to the effects of the use of agrochemicals on the Ananas Panama, S.A. plantation, linked to the Pataro family, one of the most prestigious names in the local jewelry business. According to a list that the Ministry of Agricultural Development (Mida) provided in 2018, substances such as diazinon, an insecticide banned in 32 countries and potentially carcinogenic, were used in this pineapple operation.

Diuron, a highly dangerous and carcinogenic herbicide, and glyphosate, with carcinogenic potential, one of the four most widely used herbicides in Panama, were also identified, even though spraying with this chemical was suspended in neighboring Colombia in 2015.

Also used were chlorpyrifos, a restricted-use insecticide that is toxic to bees; carbendazim, a fungicide toxic to production, mutagenic and banned in 29 countries; and the acutely toxic oxamyl insecticide, among others. These substances are ingredients of products registered in the List of Registered Phytosanitary Supplies of Mida’s National Directorate of Plant Health (DNSV, in Spanish), updated in April 2020.

Since 2016 Moisés Montero, his wife Neila, and their daughter Keila; Isadora Rojas and her family; and other neighbors have reported health problems. Allergies, pain in the glands and in the ears, eye irritation, vomiting, itching, weakness, fainting, high blood pressure, and respiratory problems, among others. The closest health center that operates regularly is in El Espino, 45 minutes away.

“My daughter began having allergies, vomiting, her eyelids were swollen… Once she missed 22 school days, she was four years old. An allergist was running tests at the Children’s Hospital. She didn’t turn up allergic to anything, they told me that it was in the environment,” said Moisés, who earned a living raising chickens and pigs before his property was taken away. He now drives for Uber.

The health problems are related to agrochemicals which are applied by Ananas Panama and Colorada Fresh Pineapple, whose use must be regulated by authorities. The Montero house is between the two plantations, which is why he has become the communities’ watchman to hold accountable the pineapple activity.

Humble, affable but firm, he has been challenging both companies for years. He sued Ananas in the La Chorrera courts for air and soil contamination due to the use of pesticides, but the case was suspended without proving the charges against the company.

Neighbors Aquilino Lorenzo and his wife Fidelina Alonso, far left, have denounced health problems affecting their family. (Tova Katzman/CPI)

In 2018, a judge ordered the seizure of Moisés and Neila’s farm after they filed another complaint with MiAmbiente that was also unsuccessful. Ananas sued the couple for $25,000 for “moral damages.” But this time, the court did not agree to the pineapple company’s claims to penalize the Monteros for their complaints to the authorities and the media.

As for Colorada Fresh Pineapple, Moisés records the operations on the property as proof of contempt for the stoppage order that MiAmbiente issued in May. “They are committing several environmental crimes, with open impunity,” said Attorney Susana Serracín, from the Alliance for Conservation and Development, who filed a criminal complaint against the company last year for “negative impact on the environment, sources of water and human health.”

On September 22, the Mida responded to a request for information that Moisés sent days before, in which he requested the data sheet of the agrochemicals used by Inversiones JPW S.A. The entity claimed not to have those records. Nonetheless, after receiving a list of questions as part of this CPI-Concolón investigation, the DNSV responded that producers are required to keep a record of the agricultural products used, including agrochemicals, which must be registered in the country.

Strangled Rivers

A business brochure looking to attract investors interested in buying a pineapple production lot —the hectare is available starting at $99,500— shows information on the use of fertilizers that contain potassium, nitrogen, and phosphate. It also mentions the application of fungicides, herbicides, and growth hormones.

The presence of nitrogen and phosphate in the Caño Quebrado River basin is not recent. It is documented in a report dating from 1999. These two substances accelerate the excessive growth of algae, which results in a lack of oxygen available to the rest of the aquatic species.

In 2001, Carmelo Martino, an official of the then National Environmental Authority, warned about the “large number of agrochemicals” used in pineapple crops, stressing the need to protect water sources and children’s health. A diagnosis of the sub-basins of the Los Hules, Tinajones and Caño Quebrado rivers recommended in 2002, cutting back on the use of pesticides and evaluating the “leaching potential” of these substances in the pineapple zone. It also warned about problems for aquatic life due to the levels of oxygen present in the waters of the first two rivers.

It is a prediction that seems to be fulfilled today. Where the Los Hules and Tinajones rivers meet, Antonino Váldez, a farmworker who has organized the nearby community of Cerro Cama to face the environmental risks associated with pineapple production, says “the water turns a dark color, which shows that it doesn’t have oxygen, and that’s when fish mortality happens.” The same thing happens in Caño Quebrado. The pollutants end up in the water due to intense rains or periods of drought that reduce riverbeds in scenarios of variability as part of climate change, said Mario Arosemena, biologist and associate researcher at the Institute of Environmental Sciences and Biodiversity of the University of Panama.

MiAmbiente’s inspection in January showed the use of regulated pesticides in the Colorada Fresh Pineapple plantation. Although its use is not banned, it should be restricted or conditioned to special handling. This information is detailed on the product labels.

Since 2011, the Mida has prohibited through a resolution the application of this type of chemical near schools, homes, water sources and other areas classified as critical areas. Resolution No. 42 created a security or buffer zone of 246 feet, to protect the health of the population. The first “10 meters that separate the critical areas from the borders of the crops should not be used for agricultural activity.” In the remaining 65 meters, the application of restricted agrochemicals is prohibited.

The Colorada Fresh Pineapple plantation violates these regulations every time it fumigates —every other day, according to testimonies— in parcels that run in the direction of a dammed stream, in others located a few meters from the houses of Calle La Esperanza, and 15 or 20 meters from a well from which water is extracted for more than 100 families.

Corporate Ties Behind a Harvest

Colorada Fresh Pineapple is surrounded by a web of companies that begins in Panama and goes through Guatemala, only to circle back to Panama.

Colorada Fresh Pineapple’s CEO, Gooden, appears on the Opencorporates website linked to at least seven companies established in Panama, including Inversiones JPW S.A. and Estoril Panama Corp. The latter runs the business of North American, European, and other investors from other parts of the world, who have property titles in the Colorada Fresh Pineapple farmlands. In an advertising video, Gooden, also president of Estoril Panama Corp., invites those interested to visit the plantation and taste the pineapples.

On September 14, 2021, Inversiones JPW S.A. and Estoril Panama Corp. appointed Donald Jerome Ewert as its general representative. According to his public profile, he has experience as a real estate agent in California and with land development projects in Colombia and Costa Rica.

Among the powers granted to Ewert by the shareholders’ of the two companies are: acquiring goods, meeting financial responsibilities, signing contracts, representing the owner or whoever grants the power in any administrative procedure.

He was also authorized to endorse or transfer shares issued by Guatemalan firm Oxec, Sociedad Anónima, as well as negotiate and sign documents and contracts.

Oxec, established in 2011, owns a hydroelectric project whose construction caused an environmental conflict with the affected indigenous communities in the department of Alta Verapaz. In turn, it belongs to Energy Resources Capital Corporation, registered in Panama in 2011, and whose shares were transferred in 2016 to another corporation with the same shareholders, ERC Capital Corp.

No Hope for Health

In Panama Oeste, Isadora Rojas filed a claim against Inversiones JPW Panama before the Ministry of the Environment, Mida, and the justice of the peace. In her complaints, Isadora does not mention Inversiones JPW Panama, but she uses the commercial name, Colorada Fresh Pineapple. In 2019, she sent a letter to the justice of the peace, Oscar González, but she got no response.

Isadora Rojas’s son, Cristián, suffers from Duchenne muscular dystrophy, an inherited disorder that mostly affects boys. (Tova Katzman/CPI)

“If those who are in charge and who are supposed to take care of us don’t do it, what are we going to do if they don’t help us,” she stressed. This investigation tried to get a reaction from the Municipality of La Chorrera, but they claimed they did not know about this complaint, even though each municipality must keep statistics on the matters that the justice of the peace attends to.

The problem of contamination by agrochemicals and its effect on health is not new. Between 2001 and 2005, a study by the Gorgas Commemorative Institute for Health Studies, the oldest and most prestigious scientific institution in Panama, identified that the district of La Chorrera had eight of the 16 jurisdictions with the highest cancer incidence rate at the national level. On top of the list are the districts of Amador, Herrera and La Represa. All located in the sub-basins of Los Hules-Tinajones and Caño Quebrado.

Among the environmental risk factors that the report mentions, is “the use of the area as a zone for high-volume use for cultivation (especially pineapples), in recent times (from the 1980s).”

Among the chemicals mentioned for their carcinogenic potential are the herbicide diuron and the fungicide mancozeb. There is evidence of the use of the first in recent years in the La Colorada production area. According to data from the National Cancer Registry, in 2018 there were 440 deaths from malignant tumors in Panama Oeste, the highest figure in seven years. The number of cases increased from 646 in 2014 to 1,332 in 2018, decreasing to 1,156 in 2019.

Regulators’ Failures Are Gains for Some

The experts consulted emphasized the need for water and soil monitoring to determine the potential effects of agrochemical contamination. Although Mida assures that it has the “suitable and trained personnel for taking and sending samples to the laboratory for quality controls,” this has not been done in a sustained manner during different government administrations.

Among the powers granted by Act 47 of 1996 to the DNSV, are supervising the use of pesticides and fertilizers, and the laboratories responsible for toxic residue analysis. It is a shared responsibility with the Ministry of Health (Minsa), which, through the General Directorate of Public Health, has the power to authorize the importation of potentially dangerous substances, in accordance with Executive Decree 305 of 2002. The DNSV list includes 18 restricted use pesticides; 73 are prohibited in Panama.

In theory, the General Directorate of Public Health can, with the Technical Directorate of Pesticides, suggest the lists of chemicals to be restricted or eliminated, and that will be managed by the secretariats of international conventions that Panama has signed such as that of Montréal and Stockholm. But so far this has never happened.

The Rotterdam Convention is aimed at regulating the international trade of pesticides that can affect health. In Panama, the sixth article of Decree 305 of 2002 —signed two years before Rotterdam went into effect, during President Mireya Moscoso’s administration— states that the entry of these chemicals is allowed for “certain registered uses.” However, the entities in charge of oversight —the ministries of Agricultural Development, Health, and Environment— often clash against each other.

“In general, the existing legislation is often dispersed in different regulatory entities and may even contain contradictions and overlaps of jurisdiction and functions and responsibilities,” states an analysis on management of chemical substances prepared by the Minsa in 2005. The limitations in budget and staff doom these tasks to a “very weak performance.”

Something similar happens with the provisions of the fifth article of Decree 305: “All substances that are prohibited or severely restricted in at least four States [countries], will also be prohibited in the country.” And yet, Mida’s list of phytosanitary imports includes pesticides that are prohibited in up to 115 countries, such as endosulfan, registered locally by a Costa Rican company. This opens the door to unrestricted importation and marketing.

Multinationals such as Shandong Weifang Rainbow Chemical, one of the heavyweights in the Chinese agrochemical industry, take advantage of these loopholes. The company is present in 70 countries, almost all in South and Central America. In Panama it operates through, a company through which it markets, imports and exports agrochemicals. It’s the official subsidiary. But it is not the only one they have in Panama.

Dangerous Agrochemicals “Made in Panama”

Far from the fertile mountains of La Chorrera, on the banks of the Canal, are the operations of Rainbow Agrosciences (Panama) S.A. The company, registered in 2012, appears on the list of active companies within the Panama Pacific Special Economic Area. It is a select group of companies, where multinationals such as Caterpillar, Dell, 3M, Heinz, Federal Express, Johnson & Johnson and BASF stand out

From this special commercial zone, governed by its own legislation, Rainbow Agrosciences formulates, manufactures, and exports agrochemicals that are dangerous for the environment and human health. One of them is Deltaprid, which, according to the product’s label, is an insecticide composed of deltamethrin, a substance that can alter the metabolism and the human reproductive system; and imidacloprid, a pesticide highly toxic for bees.

The company’s catalog also includes fipronil, a pesticide banned in 37 countries. Bolivia has been one of the export destinations for Rainbow Agrosciences, with fungicides and insecticides, including abamectin, whose inhalation can cause death.

Although he does not appear on the parent company Shandong Weifang Rainbow Chemical’s website, since 2014 Rainbow Agrosciences has Michael Groos, a German citizen who holds the position of regional president, among its executives. In 2014 Groos announced the establishment of a plant in Panama with the vision of “increasing the capacity of the supply chain, having a more efficient distribution operation and responding more quickly to the Latin American markets.”

Rainbow Agrosciences is a non-transparent operation. Its president was Vernon Emmanuel Salazar Zurita, who resigned from his position on July 9, 2021, and was replaced by Katia Jannette Smith Chavez. The company’s board of directors changed Salazar Zurita, investigated in Panama for embezzlement of public funds in a sports project that never materialized, for Smith Chavez, who was mentioned in a corruption scandal in Colombia related to the multimillion-dollar international bribery case by construction company Odebrecht.

With a total of 127 chemical registrations in Panama, Rainbow Agrosciences, and its parent company Shandong Weifang Rainbow Chemical, is the second company with the largest number of registered agrochemicals in the country. It is only surpassed by the Guatemalan multinational Abonos del Pacífico, which has 158 registered agrochemicals and operates a fertilizer factory in Vacamonte, Panama Oeste.

Another subsidiary of Shandong Weifang Rainbow Chemical in Panama is Agroiris, S.A. Among the herbicides imported by Agroiris is paraquat, classified by the World Health Organization as of moderate risk, although capable of causing death “if the concentrated product is ingested or spread through the skin.” It is banned in 46 countries, but it is one of the most widely used herbicides in Panama, according to data from the “Current status of highly dangerous pesticides in Panama” study published by biologist Raúl Carranza last year.

This is how contamination spreads throughout the Panamanian countryside and the region. It does so despite the fact that, according to Act 47, the National Plant Security Directorate has the power to restrict, prohibit or revoke the registration, entry, manufacturing, assembly, formulation of pesticides and fertilizers, if there are “technical and scientifically proven reasons.”

Rainbow’s Toxic Footprint

Some of the agrochemicals used in the plantations in La Chorrera are registered by Rainbow Agrosciences, among them diuron and glyphosate. It is an issue that should set off alarms, especially when the Canal Authority promotes sustainable development in its hydrographic basin and conducts studies to guarantee the water supply.

In the last seven years, climate change has caused record rains and historical drops in the levels of the reservoirs in the lakes on which it depends for its operation. This forced the adoption of measures such as draft reduction and toll adjustments. Water was not a problem in 2021 since it rained abundantly, which allowed the Canal to operate at its maximum draft and exceed 2019 and 2020’s tonnage.

Much has changed since the 1930s, when Carranza’s house in La Pintada, in the province of Coclé, used to fumigate with Dichloro Diphenyl Trichloroethane (D) to eradicate the mosquitoes that transmitted malaria. Later, in the 1970s, the commitment to agrochemicals came as a way to modernize agriculture.

Today, Panama not only imports and uses harmful chemicals in its fields, but also produces and exports, participating in a global market that in 2020 was valued at $4,800 billion, according to a BBC report. It’s a business controlled by multinationals such as Bayer, BASF, Yara, Syngenta, among others, and that has as local references Fertilizers of Central America, Melo Companies, Rocasa and Cruz del Sur Duwest, among others. It is a path away from sustainability and threatens health.

In this context, the strict application of the laws that regulate the use of these products and the monitoring for toxic residues is essential. As Jaime Espinosa González, a late scientist from the Agricultural Research Institute of Panama, predicted in a 1984 essay: “What is of greater value, the costs of those controls or our lives?”

This investigation was made possible in part with support from Para la Naturaleza, the Open Society Foundations, and the Fondation Connaissance et Liberté (FOKAL).

Someone need to see this article and help these people this is so sad

Wow! I am saddened by the lack of empathy for the lives of the farmers who struggle daily to survive. I’m also proud of the same farmers who are standing up to the “big trillionaires” of the world, specially when this is an environmental chaos they are living with. Doesn’t the giant EPA not get involved with such catastrophe? These poisons and chemicals are not gonna only seep into their waters but also in all waters of the world! The entire nations of all nations needs to be involved. I sure hope these chemicals will be discontinued in the near future. May God bless these farmers and their families!