Protesters in Dorado, Puerto Rico on Saturday, February 12, 2022 (Photo by Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

DORADO, Puerto Rico — On Saturday, hundreds of Puerto Ricans climbed the rocky paths that surrounded Dorado Beach to protest the decades-long privatization of one of Puerto Rico’s most prominent natural resources.

By law, every beach in Puerto Rico should be open and accessible to the public, but the last few decades have seen private beachfront hotels and apartments creep onto the coastline, essentially privatizing some beaches unless a person is staying at one of these many expensive developments or if they choose to brave dangerous paths that lead into these beaches.

Dorado Beach, a Ritz-Carlton Reserve, is one of these examples. Over the years, multiple people have complained that they were denied access to the ostensibly public beaches because the development declared that they were on their property.

This culminated in a Saturday protest demonstration at Sardinera Beach, which protesters have now dubbed “Ghetto Beach.”

(Photo by Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

Day at the Beach

“We’re here reclaiming what’s ours both as fishermen, as citizens, and as contributors to our country. We have our rights and have to reclaim them for ourselves because it’s ours,” fisherman Victor García told Latino Rebels while standing on the large rocks and stones that make up the public path to Dorado Beach’s “private beach.”

Just spoke with fisherman Victor García who’s previously only come to this area through the sea via kayak, boat, etc… But he’s told me that now he knows his rights to the beach, he’s gonna come way more often. pic.twitter.com/8JWsE2TkR2

— Carlos Berríos Polanco ⚰️ (@Vaquero2XL) February 12, 2022

In order to get to the places where García was standing, beachgoers have to walk past Sardinera Beach and onto what Dorado Beach had previously called its “private beach.”

So this is the type of terrain that the public has to pass through because there’s not easy access to the beach pic.twitter.com/cFX99px8zy

— Carlos Berríos Polanco ⚰️ (@Vaquero2XL) February 12, 2022

While people passed through, multiple protesters noted the lounge deck that was built directly onto the path that obstructed an easier way through.

The type of structures that are built right on the rocks that make an already cumbersome climbing experience worse pic.twitter.com/1YB5mSUWBi

— Carlos Berríos Polanco ⚰️ (@Vaquero2XL) February 12, 2022

Later in the day, a protester climbed onto the deck and threw one of the lounge chairs onto the rocks, destroying it completely.

García, who’s been fishing in and around Puerto Rico since he was five years old, had only ever accessed the blocked-off portion of the beach by kayak. But after fishing there on Saturday, he promised to continue coming into the area through land because it was a “great spot for good fishing.”

“It’s ironic that we have a few meters of public pathways yet we have to go through these stones while knowing that there’s a piece of land that’s supposed to be ours. What they’re causing here is that we could have an unnecessary accident,” García said.

While there were no major accidents over the course of the day, multiple people said emerged from the rocks with fresh cuts and bruises.

“I never would have come if I had known it was going to be this difficult,” one elderly protester told Latino Rebels while leaping over a gap in the rocks.

When questioned, one security guard said that the “normal path for the public” is through a series of jagged rocks but the “high tide” meant that they were letting people through a small piece of land that intersected with Dorado Beach private property.

When I asked security guard what path to take, they told me normally you’d go through the rocks but high tide is making it so that they’re letting us pass through a little grass spot. pic.twitter.com/7hMGvojPAi

— Carlos Berríos Polanco ⚰️ (@Vaquero2XL) February 12, 2022

Back on Sardinera Beach, Movimiento en Defensa de Nuestras Playas (The Movement to Defend Our Beaches) set up multiple tents where protesters were given access to free food and water.

@latinorebelstiktok Today in #dorado #puertorico

They also held classes throughout the day, including zumba and kickboxing. Just before nightfall, the group organized a beach cleanup.

“We’re raising our voice to say that the beaches are public domain for everybody to use,” Movimiento en Defensa de Nuestras Playas spokesperson Wilmar Vázquez González told Latino Rebels.

Vázquez González and the group’s organizing committee had previously attempted to go into the beaches past the rocks but found that it was difficult. The group was also responsible for organizing a previous anti-beach privatization protest in Ocean Park at the end of January.

The two protests are a study in contrasts, according to Vázquez González. He said that when attempting to access the beach through the private Ocean Park neighborhood, security guards would let anyone through if they said they were going to the beach. In contrast, Dorado Beach continually denied them and multiple others access through its neighborhood.

Private Property, Public Beaches

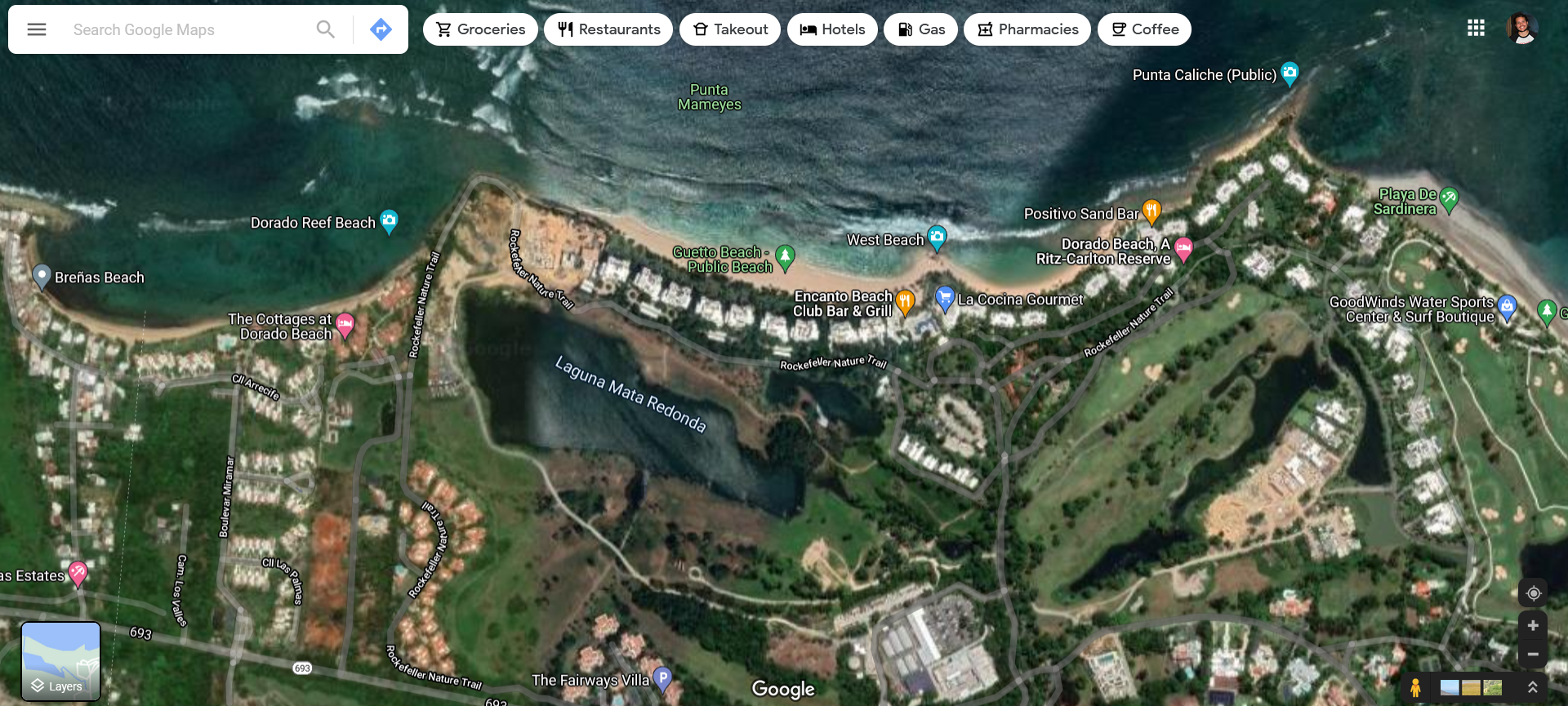

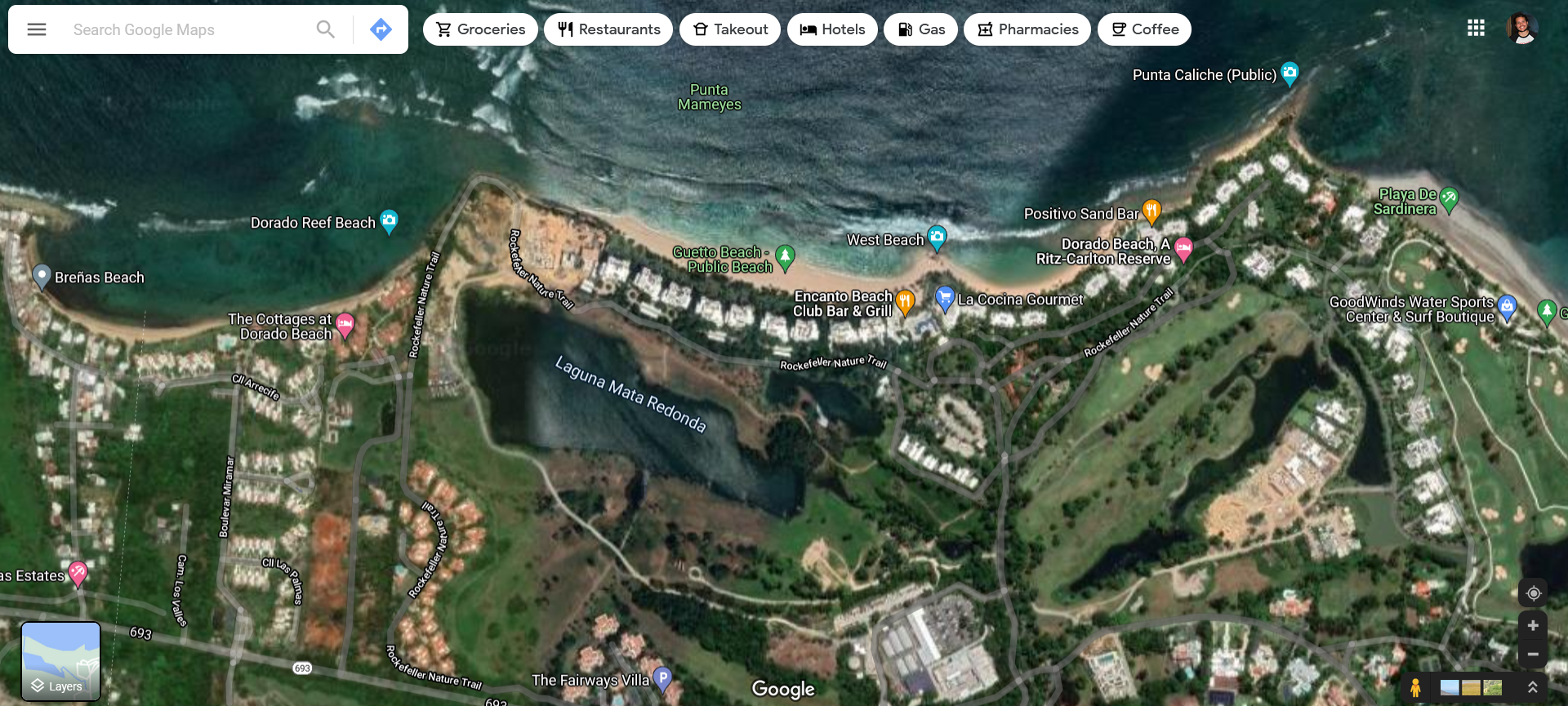

In the days leading up to the protest, Dorado Beach sent a letter to its residents, saying that there would be “an atypical event occurring this Saturday at our coastline, resulting in increased security and operating adjustments to guarantee the harmonious atmosphere we are accustomed to in our community.”

The same letter claimed that Dorado beach has “always concurred with applicable law” that Puerto Rico’s beaches are public “even if public access to some is more inconvenient and difficult to their morphology and natural characteristics.”

But as late as last November, Dorado Beach’s website advertised its Encanto Beach Club came with a “private beach.”

At press time, the advertisement has been changed to drop the “private” modifier from the beach.

Screenshots from a private group chat composed of Dorado Beach East residents obtained by Wapa-TV’s Cuarto Poder revealed that residents were petitioning Google Maps to erase the “Ghetto Beach” location marker that had been created by Puerto Ricans as a symbol of resistance against beach privatization.

Puerto Ricans created another location marker titled “Playa Ghetto, Public Beach” marked closer to what Dorado Beach called its “private beach.” At press time, both of the previous markers are gone and have been replaced with a “Ghetto Beach—Public Beach” location marker.

The beach was given the “Ghetto Beach” moniker in reference to an interview conducted by TeleOnce’s Jugando Pelota Dura with Federico Stubbe. Stubbe, whose company PRISA Group was instrumental in building Dorado Beach, said there would be a “great ghetto in Puerto Rico” if Act 22 was eliminated.

No había visto esto de Federico Stubbe. WOW PAPO. pic.twitter.com/ugQxl6Wjyv

— La Peluca De Olivo (@LaPelucaDeOlivo) March 1, 2021

Act 22, first enacted in 2012, offers individuals who don’t live in Puerto Rico full exemption on local taxes for passive income if they buy residential property, donate at least $10,000 to a local nonprofit, and live in Puerto Rico for at least 183 days to establish residency. Puerto Ricans are exempt from being able to apply for this status.

Many of the people who live in Dorado Beach are Act 22 grantees, as was recognized by the letter sent out by Dorado Beach.

Many have railed against Act 22, including environmental activist and politician Eliezer Molina who’s been a common sight at anti-beach privatization protests.

“To me, it’s extraordinary that the people have started to understand their rights and their heritage, which is what we have to protect because it’s what people want to take from us, especially people from Act 22,” Molina told Latino Rebels on Saturday.

“This is why we’re here,” Molina said. “We’re here so that people have the opportunity to see how our maritime territory assets have been stolen from us. This is what we’re trying to do here today, to visualize what the government says is not occurring.”

A protester holds a Puerto Rican flag on Saturday, February 12, 2022, in Dorado, Puerto Rico. (Photo by Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

By Puerto Rican law, there has to be a 50-meter zone of separation between any permanent structures and the maritime territory zone. Given the rising high water mark as a result of climate change, multiple beachfront buildings fall significantly closer to the maritime territory zone than the law permits.

Molina also questioned if Dorado Beach had illegally built closer to the beach than they were allowed. Last summer, Puerto Ricans protested an illegal swimming pool that was being built in Rincón that would have been built directly on top of a hawksbill turtle (carey) nesting site.

While many organizers and protesters claimed that the Saturday event was a success, it was not lost on them that it is possible that Dorado Beach would block access to its “private beach” on another day where there were fewer people and press on the beach. Nevertheless, among the cheers at Sardinera Beach or the climbing grunts on the rocks, protesters proudly proclaimed that the beaches were for everybody.

***

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco is a freelance journalist, mostly focused on civil unrest, extremism, and political corruption. Twitter: @Vaquero2XL

The governor of Puerto Rico has allowed wealthy outsiders to enjoy the beaches at the expense of Puerto Rican residents.

The “private beach” byline in the title is highly misleading because ALL beaches are PUBLIC in Puerto Rico BY LAW, which is PRECISELY the point that protesters were trying to make. By local law, ALL private properties END a set number of yards (or meters) SHORT of the high tide mark on ALL beaches and public access to ALL beaches is provided and guaranteed by local regulations every half mile or so; not only that, in the (unlikely) event that the local topography doesn’t allow for public access to a particular beach through a public road or a through public property (such as a public park), local law mandate that private properties adjoining any beach where no such public access is possible MUST provide a legal easement through said properties to guarantee public access to the beach; in fact, even Puerto Rico beaches that may be accessed only by boat, such as those found in coves and offshore islands (even privately owned ones) are ALSO public and may be enjoyed by anybody that can reach those beaches either by swimming or by any floating device or water craft.

You do realize that 1) the term is in quotes and 2) the story literally addresses why it is not a private beach. Thanks.

These protestors nothing better to do then making minorities feel scared for their families and homes.

As an act 60 resident I just donated $20,000 to the charities of the island, not to mention we still pay act 60s 4% tax which is 5m a year into PR.

This is how we are treated for giving so much to this island?

As a small minority community we need to counter protest and create campaigns to reduce this abhorrent attitude and treatment against us

Why is it that these “ultra rich” always feel as though they’re entitled to anything they can buy? If they so love “diversity” as they say they do, then why take away the diversity of the peoples of Puerto Rico as they fish, sunbathe and live around THEIR OWN BEACHES? Really people?

[…] introduced Paul as “the golden rooster”, with a “permissions clerk” and contractor Federico Stubbe. gonzo journalist Charles Polanco created a thread highlighting these issues by giving a walking […]

[…] date was still TBD) featured Paul as “the golden rooster,” with a “Clerk of Permits,” and contractor Féderico Stubbe. Gonzo journalist Carlos Polanco created a thread highlighting these issues by giving a walking […]

nobody fishes there because there are no edible fish there. reef fish are protected . so its a lie to say we wnt to fish there.

[…] Credit: Source link […]

Quit fear mongering for your racist agendas

JaBBEM stand with the people of Puerto Rico for beach Access Rights. We in Jamaica have no rights to access our beaches, walk along the shore, bathe, or fish due to the colonial era Beach control Act of 1956. Some things cannot be owned. We are fighting for change as well @jabbem.org. Free the beaches of the world