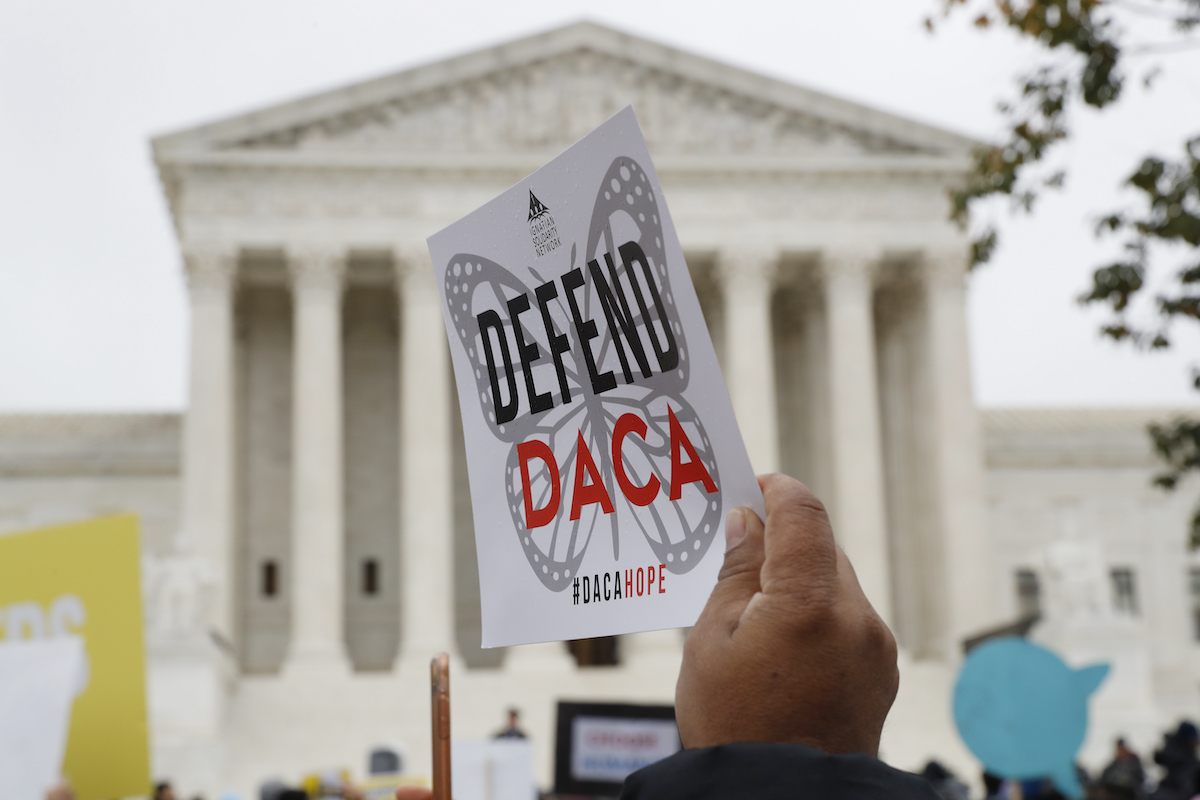

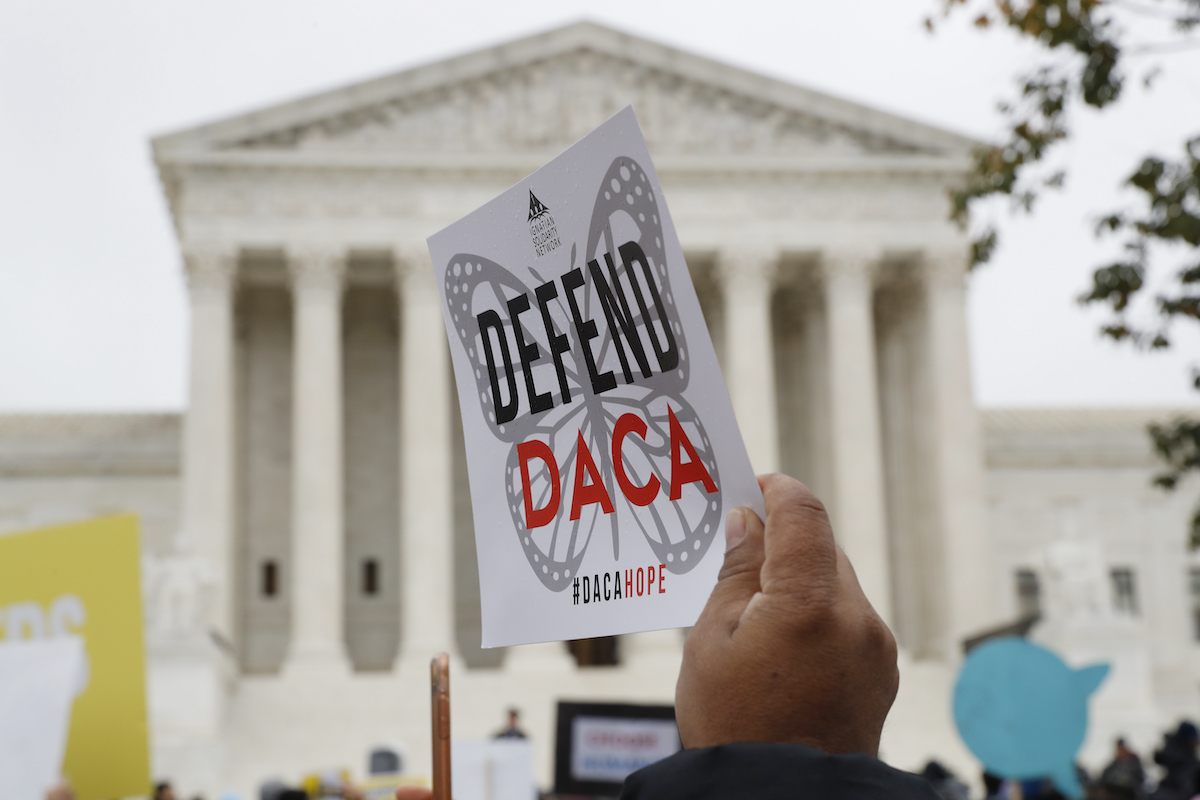

In this Nov. 12, 2019, file photo people rally outside the Supreme Court as oral arguments are heard in the case of President Trump’s decision to end the Obama-era, Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program (DACA), at the Supreme Court in Washington. (AP Photo/Jacquelyn Martin, File)

Even after President Obama first announced the creation of the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program 10 years ago on June 15, a state of limbo and uncertainty is still a constant for the thousands of recipients who initially thought the program would be the first step on their path to permanency in the United States.

“When I first got DACA, I felt so relieved. Then in 2016, reality set in. The security promised to us was no longer there.” Atziri Peña, a 24-year-old recipient, told Latino Rebels. “It’s exhausting to be in an unstable position, where you never know when DACA can be taken away.”

Peña came to the country when she was five years old and has lived here for 19 years.

Stories like Peña‘s are the norm and not the exception. DACA recipients have shared concerns and trepidations that the program was always just a stopgap. A Wednesday story by Documented commemorating the program’s 10th anniversary spoke to more than 100 recipients, most expressing similar feelings.

The program was the result of years-long activism by immigrant youth, who mobilized marches, petitions, rallies, and hunger strikes around the country. They pressured the Obama Administration to initiate some form of immigration relief, after the Senate failed to pass the DREAM Act in December 2010.

The legality of the DACA program has been repeatedly challenged during the past decade. Proponents claim the program is unconstitutional since President Obama bypassed Congress through an executive order. In 2016, the Trump Administration halted DACA, although the program was reinstated by the Biden Administration in 2020. While the program has not changed, it also hasn’t improved.

In July 2021, a U.S. district judge from Texas challenged the legality of the program again, ordering the federal government to stop approving first-time applications. Some applicants filed a motion for new applications to continue while a verdict from the Texas case is made—one that could potentially alter the lives of noncitizen youth. Until then, the fight for immigration reform continues.

In prepared remarks for DACA’s 10th anniversary that were released on Wednesday morning, Obama reiterated the current realities of the DACA debate, noting that the program “was, and is, temporary.”

“It remains vulnerable to politicians who choose to ignore DACA’s remarkable benefits to our country,” the former president said. “These Dreamers lived through the cruelty of the previous administration’s attacks and legal challenges to the program, their families, and their communities. And Dreamers graduating high school or entering the workforce today face an even steeper climb than they did a decade ago. Only a quarter of the undocumented students graduating high school this year are eligible for DACA under existing rules. Some states restrict in-state tuition from undocumented students, even when they meet all residency requirements. And some professions remain out of reach because of a patchwork of unreasonable state-level licensing requirements.”

The Biden Administration and Democrats insist that DACA must be protected although there is no concrete legislation that is moving quickly through Congress. The White House planned for a Wednesday morning virtual session which will include a video message from President Biden, as well as remarks by Department of Homeland Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas and others to highlight “the transformative impact of the policy and the need for a permanent solution,” according to an official media release.

Ten years ago today, I stood by President Obama as we carried out one of our proudest accomplishments. On this 10th DACA Anniversary, we celebrate the transformational impact it’s had on hundreds of thousands of young people.

It's time for Congress to make this permanent now. pic.twitter.com/03GyhwRtae

— President Biden (@POTUS) June 15, 2022

Nonetheless, the initial hope from 10 years ago felt real and tangible to many recipients and their families, sparking the promise of a new movement for undocumented rights.

“When I first heard of DACA, I was roughly around 17 or 18 years old. I remember the hope in my mother’s eyes when she said, ‘Vas a tener más oportunidades que nosotros.’ (‘You are going to have more opportunities than us.’),” Jennifer León, a therapist and a DACA recipient, told Latino Rebels.

DACA provides noncitizen youth with the legal right to live and work for a fee of $495 that needs to be renewed every two years. The program requires that a recipient must have arrived in the country before the age of 16, possess no criminal record, and hold a high school diploma or a GED. According to a report by Boundless, there are currently about 611,470 recipients in the country and the majority are between 20 and 30 years old.

Since then, recipients have aged into adulthood without a clear image of what the future holds for the program.

“My biggest concern is a return to challenging emotions that keep me in survival mode and the obstacles that would limit me from providing mental health services to our community. With the 10th anniversary of DACA, these thoughts are still present,” León said, who noted that she still has no reassurance her rights will not be stripped away tomorrow.

Throughout the course of the program, recipients pursued higher education degrees, purchased homes, or started families with their earnings from legal employment—pursuits that would have been doubly difficult without a form of legal documentation. According to the left-leaning Center for American Progress think thank, recipients paid $9.4 billion in annual taxes and their households held $25.3 billion in spending power.

Meanwhile, younger noncitizens who missed out on DACA started adulthood without the same privileges. Brenda, 23, who arrived in 2014, told Latino Rebels that “the media has a strong focus on DACA. People forget about the existence of us who do not have access to the program, due to financial struggles, age, and not meeting the 2007-2012 requirements.”

They must learn how to navigate education, if attainable, and employment without a work permit.

“I recently graduated from a university with two bachelor’s degrees—in Business and Spanish. Because I do not have DACA, it is nearly impossible for me to be employed and work in the fields of my degrees, so I cannot get experience unless it’s unpaid or volunteer work,” Brenda said. Currently, she runs her own candle and beaded jewelry business to make ends meet.

Another woman, Dulce Ortega, 25, and her brother missed the application by a few months.

“I was discouraged to say the least because at the time, I felt that six months were keeping me from my dreams of becoming a social worker. I did not tell anyone because at that time, I had not really disclosed my status,” Dulce said.

Brenda’s and Dulce’s mental health suffers from concealing their undocumented status, which they do not feel comfortable disclosing without protection from deportation. Protesting and activism work are risky ventures, and they are reluctant to participate because they fear the possibility of deportation. There are many others like them, who under American law are illegally present in the country—all because they didn’t make the cutoff date of an arbitrary deadline.

“Now, I understand the program provides a false sense of stability, keeping us limited to a two-year renewal at a high cost of emotional damage with a $495 price tag. DACA is a pawn on a privileged chessboard,” Jennifer said.

***

Yesica Balderrama is a journalist and writer based in New York City. Her work has appeared on WNYC, NPR, Latino USA, PEN America, Mental Floss, and others. Twitter: @yesica_bald

[…] federal judge in Texas last year declared the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program illegal—although he agreed to leave the program intact for those already […]

[…] a lower court review of Biden administration revisions to a program preventing the deportation of hundreds of thousands of immigrants brought into the United States as […]