Illustration by Rachel Handley/McClatchy

By CRISTINA DEL MAR QUILES (Todas y Centro de Periodismo Investigativo), SYRA ORTIZ BLANES (Miami Herald and El Nuevo Herald), and ANA CLAUDIA CHACIN (Miami Herald and El Nuevo Herald)

SAN JUAN — Eight days before shooting and killing Iraida Hornedo Camacho, Diego Figueroa Torres signed a statement from Frente Unido Policías Organizados, a prominent police union, in which he wrote that the Puerto Rico Police Bureau “deals with all cases of gender-based violence as a public-health problem without differentiating the employment of the people involved.”

As president of the union, which he led for 17 years, the retired policeman was responding to a request from the island’s legislature to investigate protocols for handling cases and complaints of domestic violence filed against police officers.

“We are not aware that there is preferential treatment in the Puerto Rico Police Bureau when dealing with a case of gender-based violence against a member of the force, nor that the same [complaints] are not resolved,” said the document from the former agent, whose organization offers legal representation to officers in administrative, civil and criminal cases, including when they’re accused of domestic violence accusations.

A week and a day later, on October 22, 2022, Figueroa Torres killed Hornedo Camacho with the firearm he legally carried. Then he killed himself.

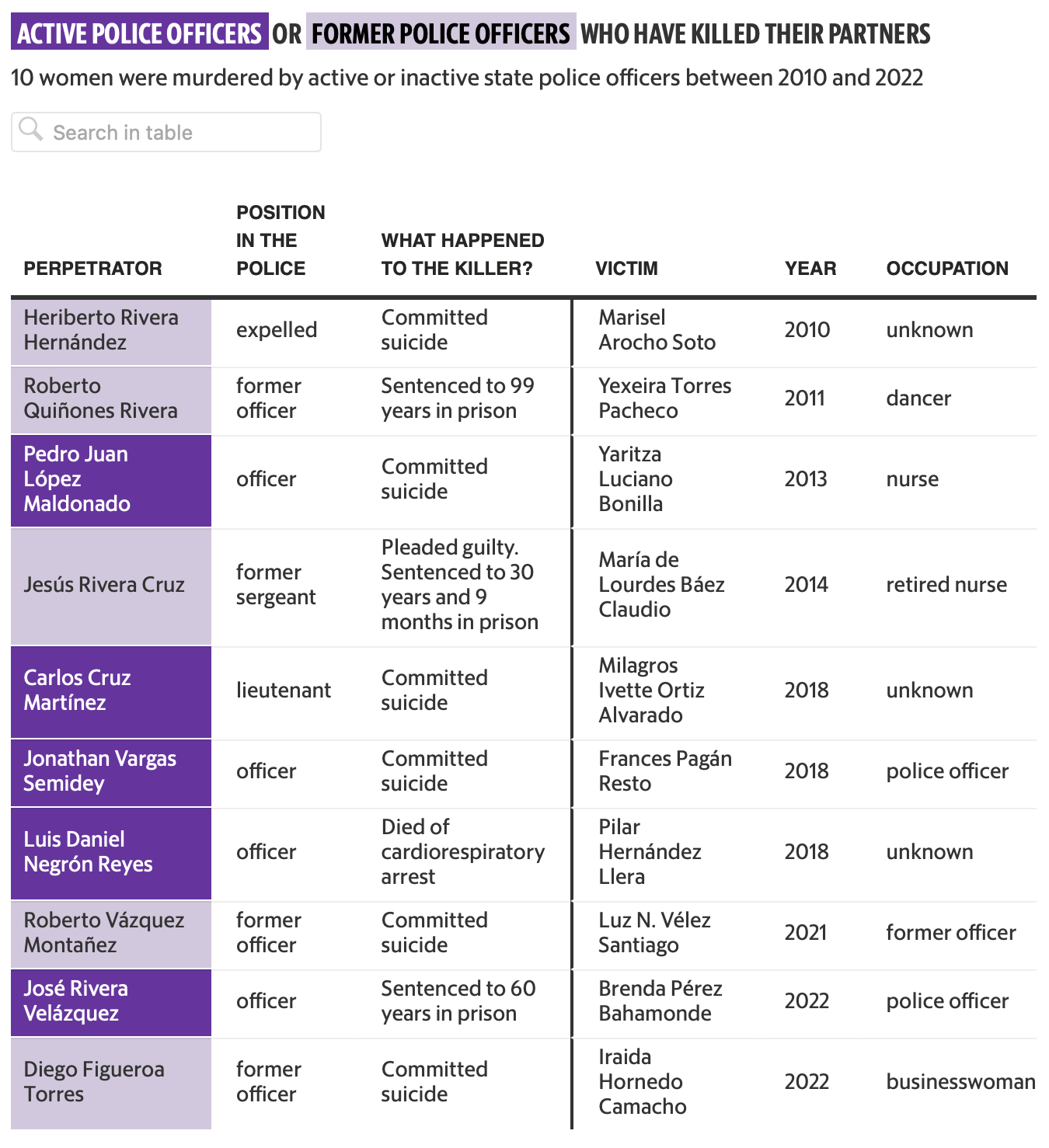

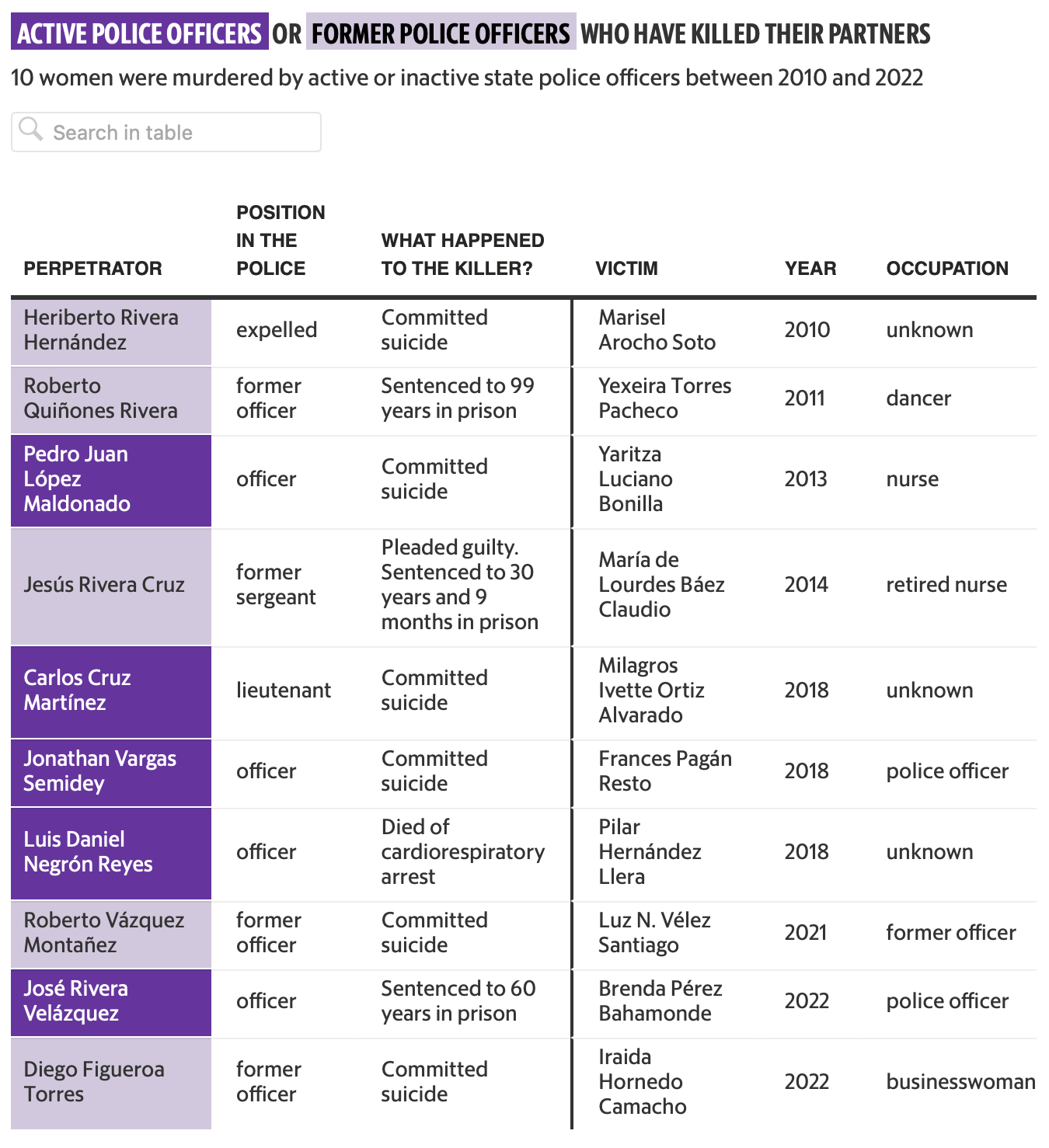

That day, Figueroa Torres became the fifth former police officer to commit a femicide in Puerto Rico in the past 12 years. Counting killings committed by active officers, there have been 10 victims of men who were officers of the Bureau. The island’s principal law enforcement agency, which had nearly 12,150 officers as of March 2022, is supposed to be a key part of the government response to the state of emergency over gender violence it declared nearly two years ago.

Yet an investigation by the Miami Herald and the Centro de Periodismo Investigativo (CPI) in Puerto Rico has identified failures in the handling of gender-based violence cases involving police officers, as well as a culture of impunity that protects the abusers and makes victims even more vulnerable.

The investigation highlights the bureau’s resistance to addressing its historic domestic violence problem, with police officers refusing to take complaints against colleagues, a high rate of arrests of officers that don’t lead to prosecution or convictions, and unreliable statistics for accountability.

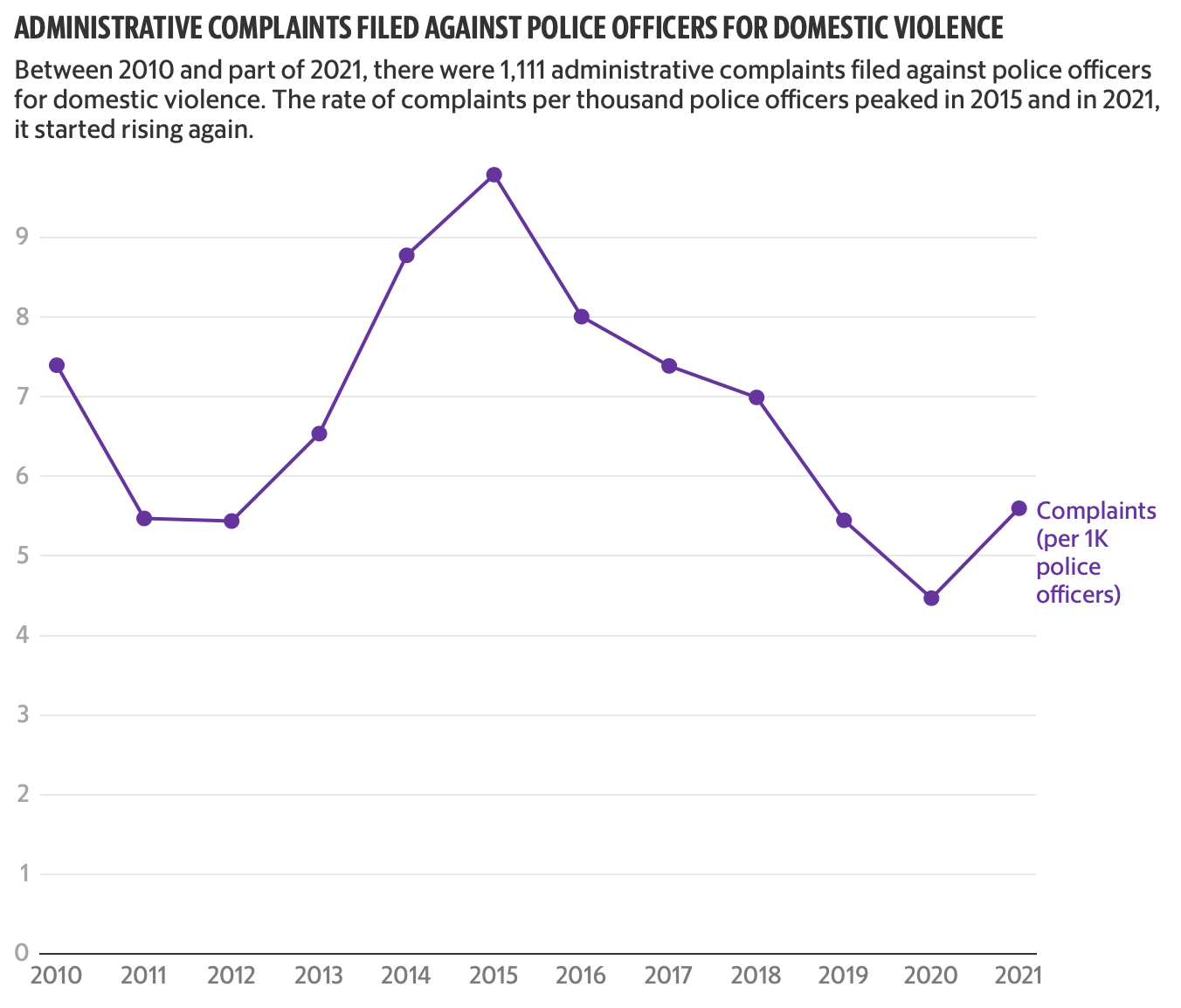

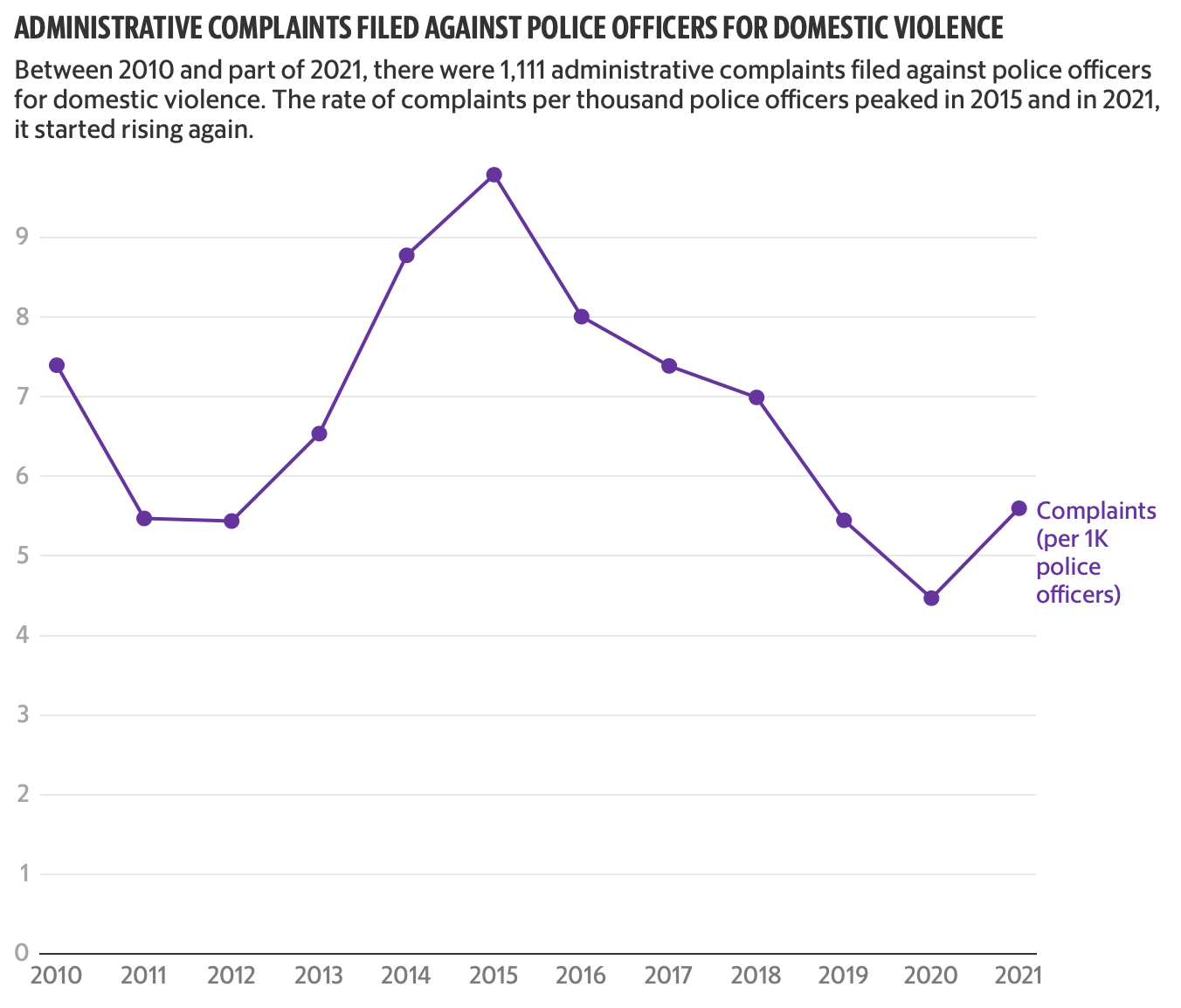

More than 800 officers were arrested in 960 domestic-violence incidents between 2010 and 2021, according to an analysis of the agency’s data. The Bureau did not say until which month of 2021 it included the data. Only 36 cases ended in convictions. In 93 percent of the cases, the officers arrested were men, in an agency in which men made up 76 percent of the force as of February 2022.

Almost 15 percent, or 118 of those officers, were arrested at least twice. As of May 2022, the agency said 46 of them had been fired or were no longer active for several reasons, including death, retirement, or resignation.

The Bureau admitted in court documents in January 2022 that it does not keep statistics on how many police officers arrested for domestic violence between 2010 and 2021 are still active, how many are on administrative leave or suspended, or how many have been fired or had their service weapon taken away.

The CPI and a Miami Herald reporter had to file a lawsuit against the Bureau in May 2021, requesting information about administrative complaints, restraining orders, arrests, and prosecution of police officers for domestic violence which the agency had refused to provide.

According to the Puerto Rico Police Bureau, administrative complaints include some against officers who refused to take complaints related to domestic violence.

Chart: Ana Claudia Chacin, David Newcomb Morales, Miami Herald, CPI Source: Puerto Rico Police Bureau

During a year of litigation, the Bureau delivered most of the information requested in more than a hundred documents. But the agency argued that it does not keep track of all the statistics required in the suit.

No Data to Guide a Remedy

The U.S. Justice Department had highlighted the Puerto Rico Police Bureau’s poor management of statistics as far back as 2011. An investigation of the Bureau that year documented multiple officer-perpetrated civil rights violations and a lack of accountability. Eleven years after the report —and nine years after a reform agreement meant to solve these issues— the Bureau for the first time produced several of the lawsuit’s documents to comply with a San Juan judge’s order.

The data revealed the continuing deficiencies in information collection. The Bureau had never before disclosed or analyzed the information provided for this investigation. It helps put in context the crime committed by Figueroa Torres, as well the recent arrests domestic-violence arrests of a Bureau sergeant and a cadet.

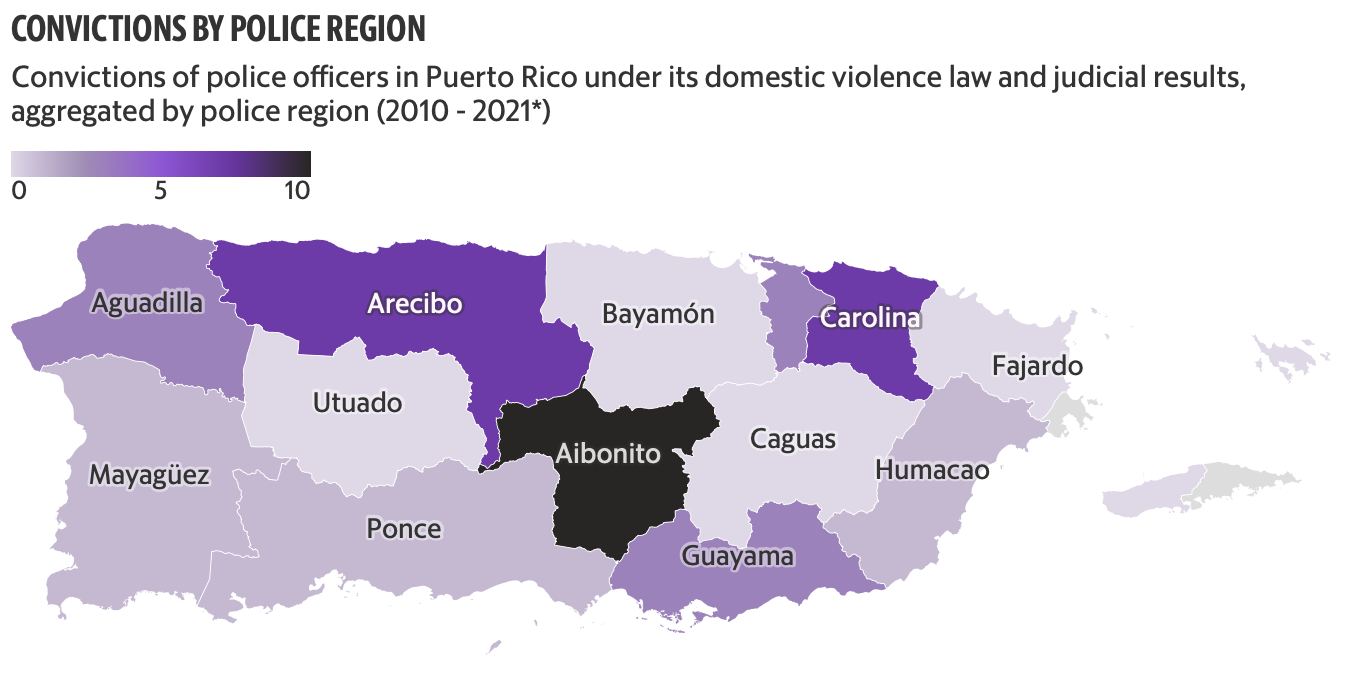

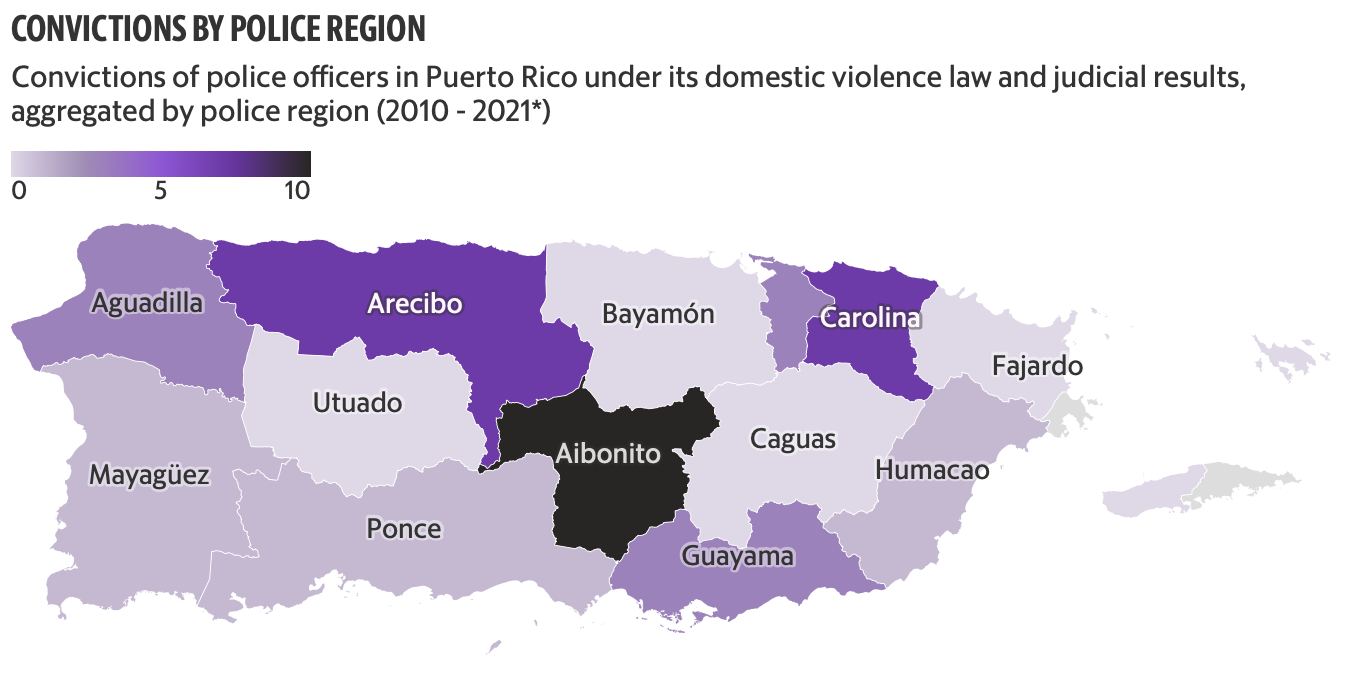

In at least three of Puerto Rico’s 13 regions —San Juan, Aguadilla, and Aibonito— the Bureau certified that it could not provide information on arrests for domestic violence against members between 2010 and 2014 because it does not have the data.

In San Juan, Aguadilla, and Aibonito, the Police Bureau confirmed that it could not provide information on arrests between 2010 and 2014 because they do not have the data. Data from 2021 is incomplete. In the Ponce police region, the Bureau certified that “there were no cases investigated” against police officers in 2013.

Map: Ana Claudia Chacin, David Newcomb Morales, Miami Herald, CPI Source: Puerto Rico Police Bureau

The Bureau’s court-ordered data disclosure was riddled with errors that required multiple clarifications from the agency. In some cases, they assigned complaints against civilians to Bureau officers. For many mistakes, there was no explanation.

The lack of information highlights the agency’s failure to maintain an accessible, centralized, and up-to-date data system, making it difficult for the Bureau to grasp the magnitude of the problem of domestic violence perpetrated by police officers.

The Justice Department was prompted to investigate the agency because of complaints about police abuse that victims’ relatives, community leaders, legislators, and civil rights activists made over several years. The agency published its findings in September 2011.

Those findings raised “serious concerns” that Puerto Rico Police policies and practices were “woefully inadequate” to “prevent or address” domestic violence involving officers. It also said there was evidence that the agency frequently failed to investigate gender-violence cases among the general public.

As a result of the findings, Puerto Rico’s government and the Justice Department signed an agreement in 2013 to reform what at the time was called the Puerto Rico Police Department.

In 2014, a federal judge overseeing the reform process appointed retired U.S. Army Col. Arnaldo Claudio as the agreement’s compliance officer. Under Claudio’s supervision, the Bureau created and implemented protocols to handle domestic violence cases involving abusive police officers. However, Claudio could document little progress over the next five years.

“Every six months we looked at the issue and every six months we found the same flaws. We did not see progress,” Claudio —who resigned from his post in 2019, saying at the time that he no longer trusted the reform process— said in an interview.

In multiple reports tracking the reform’s progress, Claudio pointed out the agency’s inefficiency in evaluating administrative complaints for domestic violence and the lack of disciplinary measures to address them.

“I think we are behind in this matter and that the Puerto Rico Police leadership has not addressed this as it should,” Claudio said.

Illustration by Rachel Handley/McClatchy

In response to Claudio’s comments, Puerto Rico Police Bureau Commissioner Antonio López Figueroa pointed out that the former monitor had left his post more than three years ago. He said he would only discuss Bureau efforts on the issue of domestic violence since he became the agency’s head in January 2021.

“Under the current administration, the issue of domestic violence is addressed as a priority and the process of administrative complaints is handled with the highest rigor and transparency,” López Figueroa said.

López Figueroa referred to a report from Claudio’s successor, John Romero, who became the federal monitor in 2019.

“The federal monitor documents that he examined files of domestic violence cases where police officers are involved. Among other things, this report shows that it is evident that the Police are proceeding with a victim-centered approach and acting with greater rigor when a member of the Police is involved,” the commissioner said.

That report, from December 2021, also indicates that the Bureau only partially complies with the requirement to implement measures to respond to complaints of domestic violence and sexual assault involving officers, including taking their service weapons away and evaluating their fitness for duty. It states that although there is a policy to address these issues, they have not been carried out.

Romero declined to be interviewed for this story. His lawyer said the Bureau and the Justice Department had turned down the request, and instead provided Romero’s June 2022 compliance report to the federal court.

Police officers are trained on civil rights, gender violence, and sexual crimes as part of the agency’s reform. But the monitor determined in the report that no police officers who were part of his sample had received training to investigate domestic violence cases involving other officers. However, Romero said in the report that “due to an oversight,” he did not request a sample of gender-violence investigations involving police officers and couldn’t assess if they complied with the reform.

Despite that track record, the Bureau commissioner says he believes he leads an exemplary agency.

“My ideal police force? It is the police that I have now, since I count on them. I count on my police officers, who are doing the job,” López Figueroa said during an interview at the Bureau’s San Juan headquarters.

The low number of domestic-violence charges filed by prosecutors compared to the much higher number of police officers arrested between 2010 and 2021 has an explanation, the police chief said: The Bureau arrests officers “even when the elements” of the crime do not exist. The commissioner argued that this is because the process against a Bureau employee “is more rigorous than for any other citizen.”

“Any domestic violence complaint involving a police officer will be consulted with a prosecutor, even when we understand from the investigation that it is not a case that should reach a prosecutor because the elements do not exist,” said Sgt. Ivette Rivera Velázquez of the Domestic Violence Unit. “We activate the protocol so that there is no doubt that the investigation was carried out and that, even so, we took it to a prosecutor to evaluate that investigation.”

She said the Bureau continues an internal investigation against an officer arrested on charges of domestic violence even when prosecutors do not file charges. López Figueroa said that there are “many frivolous complaints against the police.”

‘An Impeccable Man’

For this story, reporters spoke to several women and family members of victims, who shared their experiences of domestic violence at the hands of Bureau officers or former officers.

Their accounts have several threads in common: fear of their partner’s access to weapons; the use of police resources to intimidate them, harm them, and dissuade them from reporting; and the indifference of other police officers and supervisors to their plight.

One of them, Ana, agreed to share the details included in this story and asked to not be identified by her real name because she fears for her life. Official documents and her legal advocate, a court official who offers support to domestic violence survivors, corroborated her account.

Ana was in a relationship with a police officer, with whom she has a child, for about a decade. She said that for years she experienced mental health issues because her partner, at the time a high-ranking officer in the Bureau, abused her. She spoke about how he restricted her freedom, isolated her from her family, pressured her to stop studying and working, and assaulted her physically and sexually.

One night, months after Hurricane María devastated Puerto Rico in 2017, Ana received repeated calls from her partner while she closed up the business where she worked.

“He wanted to see that I was actually at work,” Ana said in an interview.

But he didn’t believe her, and showed up at her workplace. He accused Ana of being unfaithful to him with a work colleague, who was also there. After getting into his car, the officer tried to run over the work colleague, who was on foot, according to Ana.

“In his obsessive jealousy, he almost killed that employee,” she recalled.

The employee —who confirmed for this story that he was almost run over— fled until he stumbled upon a group of police officers.

“With the power I have, do you think someone is going to do anything to me? Nobody is going to do anything to me,” Ana recounted her partner telling her as the police officers approached his car.

The officers recognized their supervisor and greeted him by his rank. “Everything okay?” Ana remembers that the agents asked her. She said she trembled and cried nonstop, while the on-duty officers told her partner to take “things easy.”

Then they left.

That same night, Ana went to file a complaint against her partner for domestic violence. However, he followed her to the station and entered before she did.

She said the station supervisor came out and told her: “I’ve come to talk to you as a friend. I have known your partner for many years and he is an impeccable man… Look, I recommend that you go home to talk because relationship problems are discussed at home.”

When she returned home —without being able to file the complaint— he physically attacked her again, she said.

In the following months, Ana said, she went to police stations several times to try to file a complaint. At one point, she spoke with her ex-partner’s supervisor, who dissuaded her.

“Couple problems are solved at home, not at work,” she recalls the supervisor telling her. “Your coming here… can cause him to lose his job, and you know that if he loses his job, he will not have enough money to maintain your son.”

Six months after the incident in which Ana’s partner almost ran over her colleague, she obtained an order of protection in court that required the Bureau to take his firearm away. But other officers made the order’s implementation difficult, Ana said.

“In all the stations I went to, they knew him,” she said.

She said she had to travel at least five times to different stations to implement the order, and that they questioned her about her mental health.

Four years passed before the high-ranking officer was finally expelled from the force, according to a Bureau document Ana shared with the Herald.

She has since tried to rebuild her life. But even after her former partner was fired, Ana still fears what he could do.

“My situation has not yet been resolved. He continues to exercise his power against me,” she said. She referred to the multiple legal actions in family court that her former partner has filed against her and that continue to take a financial and mental toll.

The Burden of Investigating a Fellow Officer

Gender-violence victims are not the only ones who experience pressure when they report abusive officers. Police officers may discourage their peers from investigating other officers charged with domestic violence, according to experts, prosecutors, and some police officers.

Within the Puerto Rico Police Bureau, officers can be suspicious of colleagues who investigate complaints filed against their peers or their superiors.

“That happens,” said agent Nilmaliz Ramos, who works in the Domestic Violence Division in the town of Caguas, when approached while leaving court for a hearing against Sgt. Roberto García García on domestic-violence charges. At that time, prosecutor Miguel López Birriel was explaining that police officers who investigate colleagues expose themselves to peer pressure and are “shunned.”

García García, director of the Humacao Domestic Violence Division, was arrested in July 2021 and accused of violating Puerto Rico’s domestic violence law, but a judge determined there was no cause for arrest the second time prosecutors attempted to file charges against him.

Ramos and officer Alexander Ocasio, from the town of Maunabo, who were both witnesses in the preliminary hearing, acknowledged that when investigating police officers they expose themselves to pressure from colleagues.

Illustration by Rachel Handley/McClatchy

“It’s not easy when it’s a colleague,” Ocasio said. “There are officers that, perhaps, will now view you as the black sheep, but I did my job as it should be done.”

María Mari Narváez, executive director of Kilómetro 0, an organization that monitors civil rights violations committed by police, said a culture of loyalty and cover-up exists in the Bureau that protects abusers and tolerates domestic violence in its ranks, making it difficult for women to file or enforce a complaint against her police officer partner.

María Mari Narváez, executive director of Kilometer 0 (Ana María Abruña Reyes/Todas/Centro de Periodismo Investigativo)

“The police have to be the most powerful institution in the entire patriarchy,” said Mari Narváez. “You already know that when you go to report it, be it to the police or to court, the abusive police officer will find out what you intend to do probably the same day that you are going to file the complaint.”

The activist, who has monitored police violence in Puerto Rico for eight years, said that an officer who is abusive “knows the criminal legal system by heart and knows how to manipulate it against the victim. He has in his favor a system and a culture of absolute impunity.”

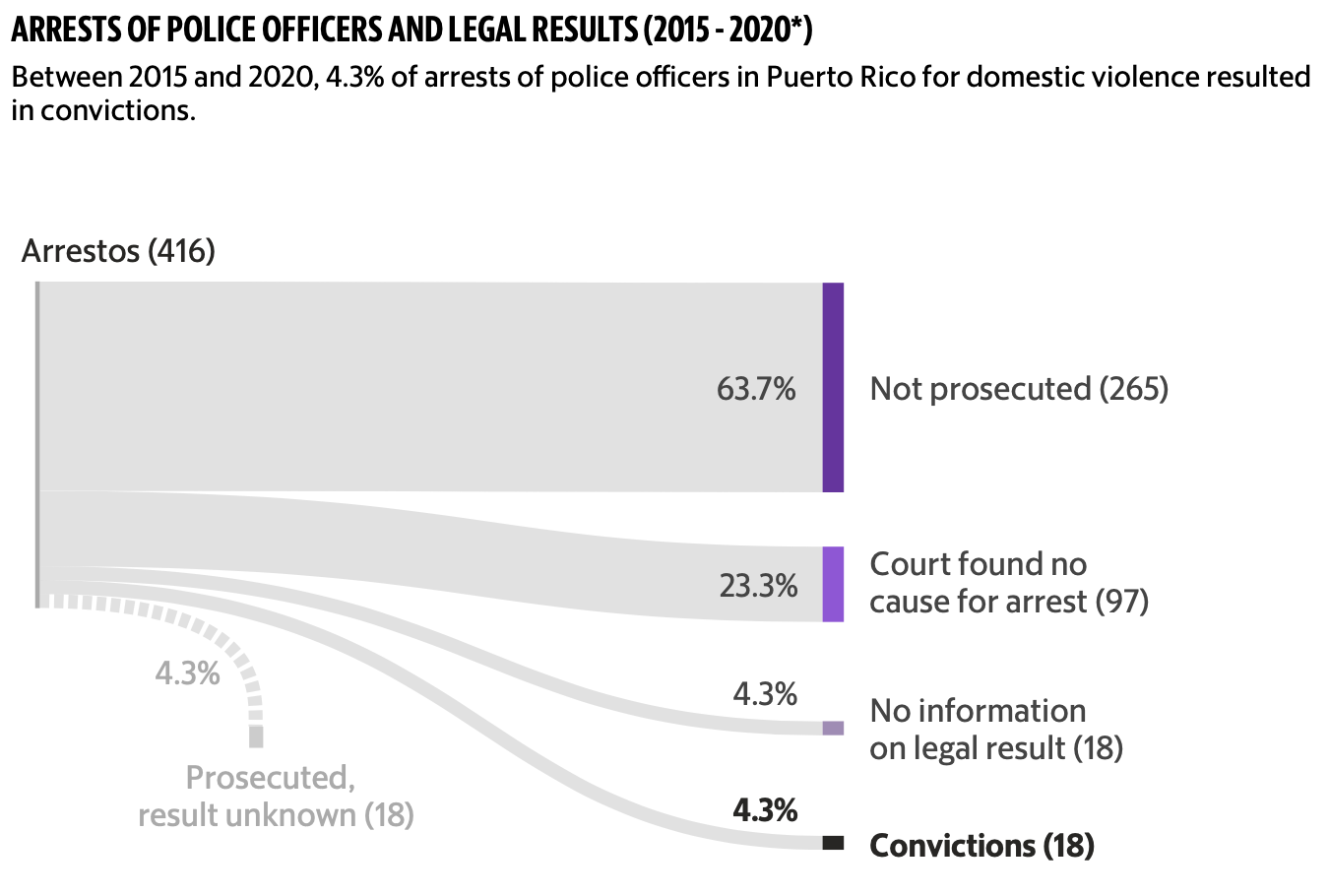

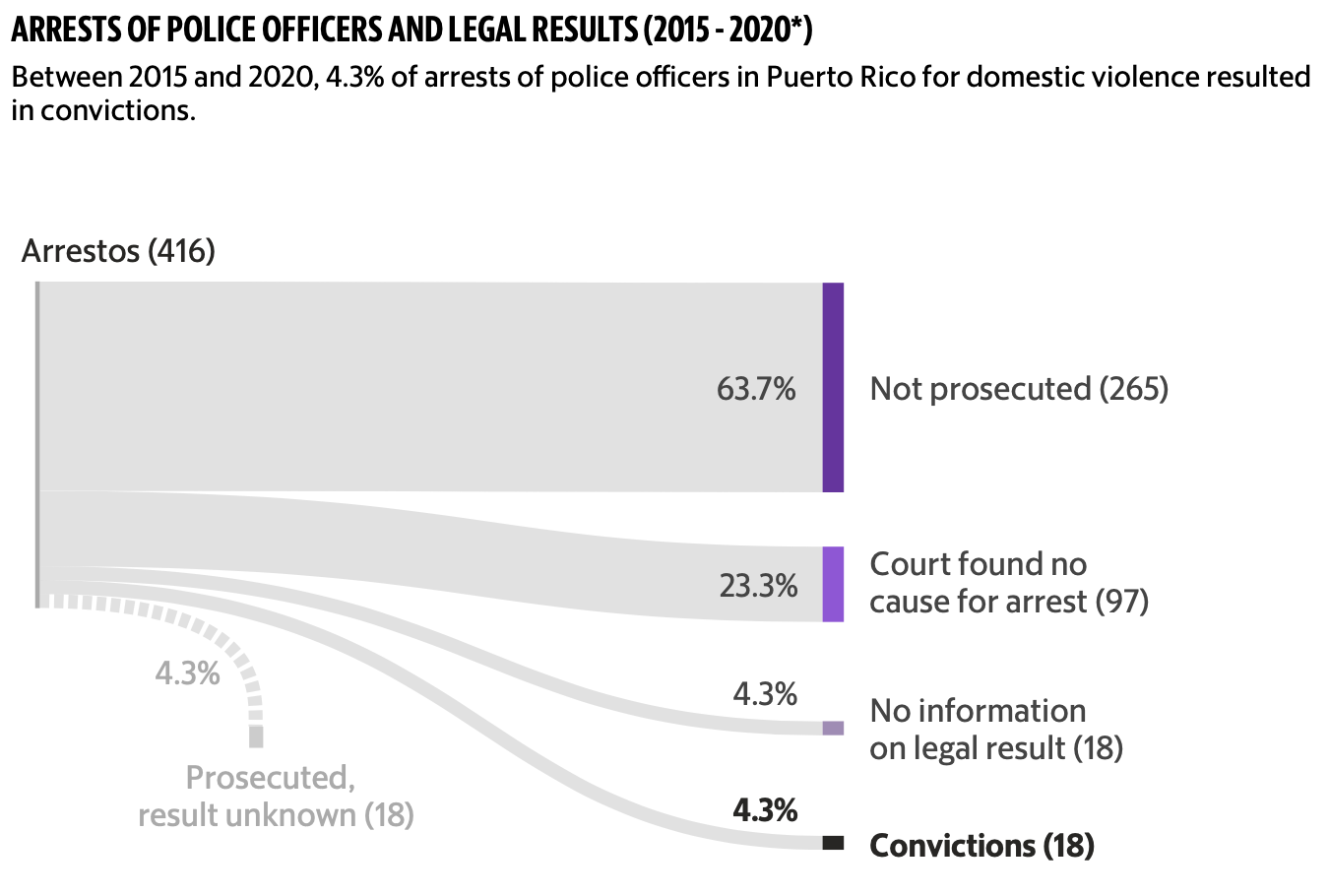

Between 2015 and 2020, 18 of the 416 arrests (4.3%) were prosecuted, but they were not counted in either the “No cause for arrest” or “Conviction” categories because their results remain unknown.

Chart: Ana Claudia Chacin, David Newcomb Morales, Miami Herald, CPI • Source: Puerto Rico Police Bureau

Abusive police officers also use the credibility their uniform offers to protect themselves and each other, Mari Narváez added.

“Who suspects a police officer?” she said.

For women whose partners are Bureau officers, fleeing an abusive situation can be more challenging if the officers take advantage of the tools at their disposal, such as knowledge of how to look for people who do not want to be found, experience in managing scenes and intelligence systems, and how to exercise control. They know where abuse shelters are and they also have the ability to carry out surveillance and fabricate cases, Mari Narváez said.

“Prosecutors are allies of the police on a day-to-day basis. Partnerships are created even if they are informal. The police have access to data, they can intimidate the victim, they are armed… All of this has a greater impact on ensuring that the cases do not come to an end,” said Mari Narvaez about why she thinks there is a difference between the domestic-violence conviction rates for officers and the general population in Puerto Rico.

While 55 percent of the women and 20 percent of the men in the general population charged with domestic violence for the years 2014-20 were convicted, according to Puerto Rico Department of Justice data, for police officers charged with domestic violence, the conviction rate was 14.6 percent during the same period.

“The system already protects police officers and does not have the necessary accountability safeguards so that the crimes of that police officer have the same consequences as those of the rest,” Mari Narváez said.

‘No Victim… Has Been Told No in a Station’

López Figueroa, the police commissioner, denied that there is impunity for abusive officers.

“Any domestic violence case that involves a police officer is taken to its ultimate consequences,” López Figueroa said, even though in 11 years there were only 36 convictions for domestic violence among 960 arrests of police officers.

The commissioner said that the perception of domestic violence victims about denouncing a police officer partner “should be that it is addressed correctly, quickly and that it undergoes the correct processes.”

“There is no victim who has been told no in a station here. It’s very difficult for that to happen,” he said in the interview at the Bureau’s headquarters.

However, Rivera Velázquez, the sergeant of the Domestic Violence Unit, noted during the interview that victims can launch administrative complaints against officers who refuse to respond to an accusation against a colleague. The commissioner’s legal adviser, Pedro Santiago, admitted that the Bureau statistics of administrative complaints of domestic violence include several cases in which victims said police officers refused to investigate their claims.

The commissioner said the Bureau is working to speed up the investigation of domestic violence complaints, including the creation of a center to manage restraining orders.

“The police are respectful, sensitive, and empathetic. And that is the police that we have today and will continue to have,” López Figueroa said.

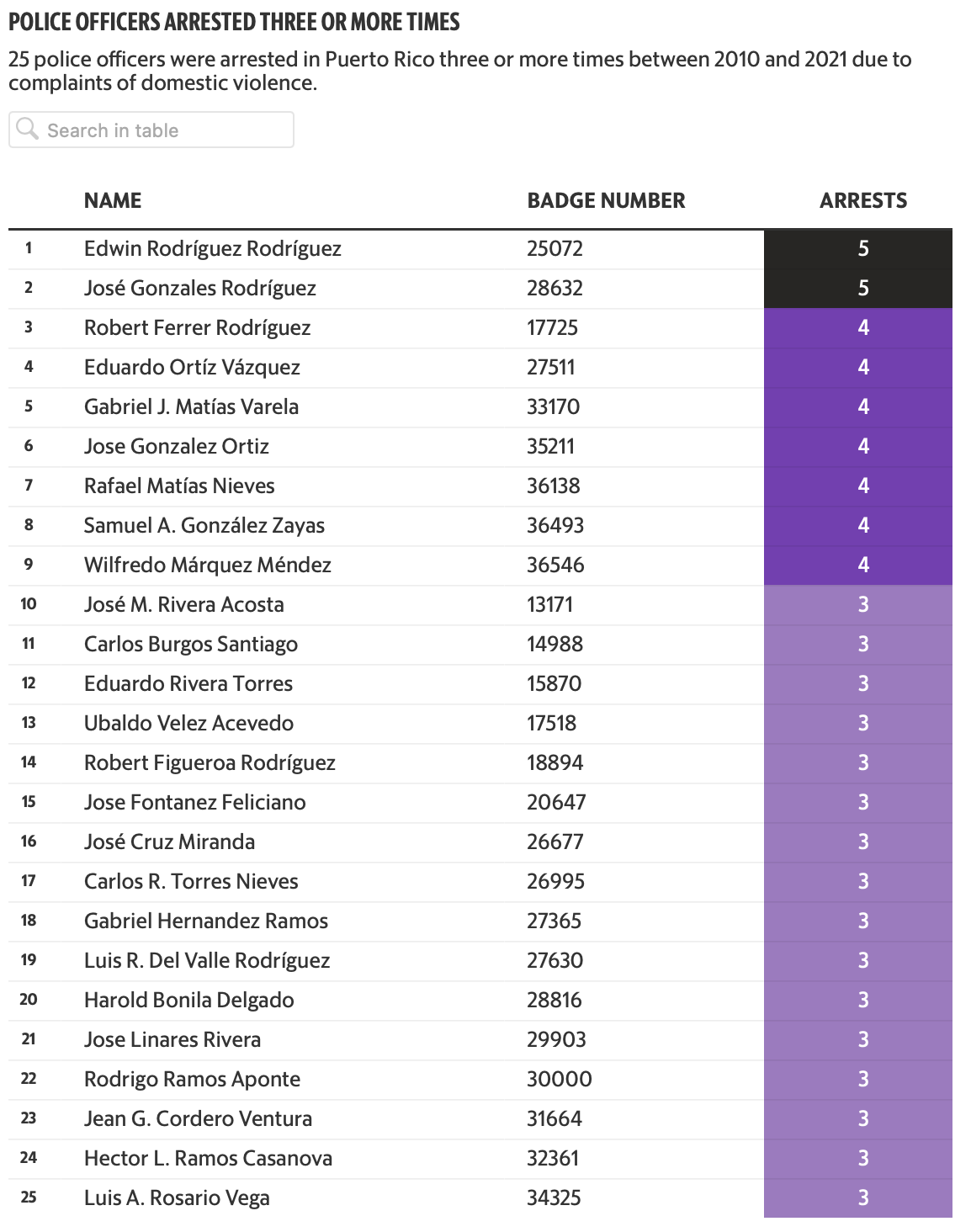

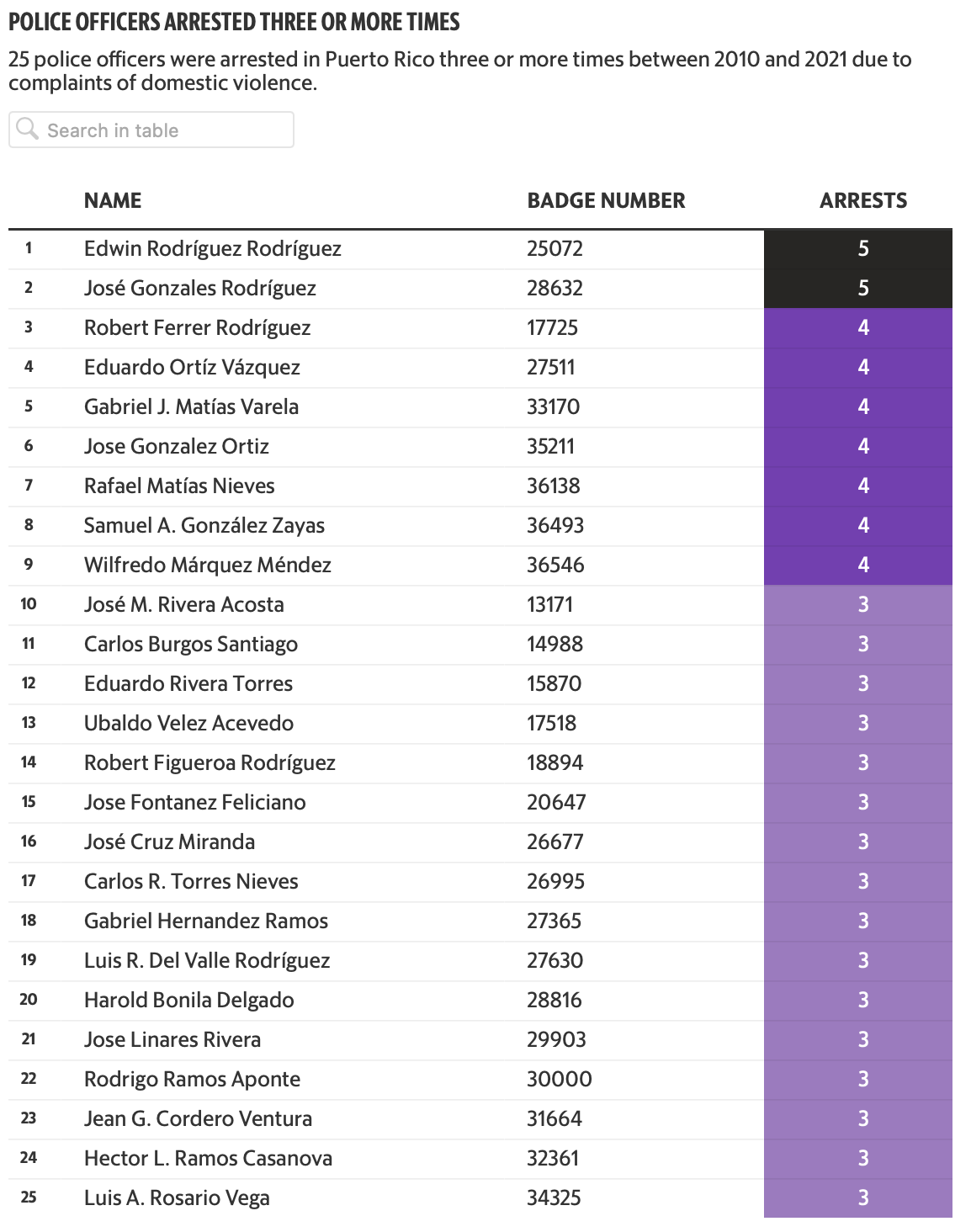

The police did not release information about the arrests of police officers for certain years between 2010 and 2014 in the San Juan, Aibonito, and Aguadilla police regions. They also maintained that there were no cases in Ponce in 2013. The information in this table was provided by the Puerto Rico Police Bureau. Several errors were identified that required clarification from the agency.

Table: Ana Claudia Chacin, David Newcomb Morales, Miami Herald, CPI Source: Puerto Rico Police Bureau

According to an analysis of the data provided by the Bureau, between 2010 and 2021, 93 agents were arrested twice for domestic violence, 16 police officers were arrested three times, and another seven were arrested four times.

Bureau data also shows that an officer named José González Rodríguez was arrested on five different occasions in 2017 and 2019. González Rodríguez did not want to comment for this story, although he acknowledged that he had had domestic violence cases filed against him and that he had also filed complaints against his ex-partner for domestic violence.

Another police officer, Edwin Rodríguez Rodríguez, assigned to the northern town of Bayamón, has five arrests for domestic violence, according to data provided by the Bureau. On four occasions, a prosecutor determined not to press charges. On a fifth occasion, the complaint was classified as “unfounded,” though a judge did grant an order of protection against him. Rodríguez Rodríguez declined to be interviewed.

The two officers with multiple domestic violence arrests continue to work at the Bureau.

Service Weapons and Domestic Violence

Between 2010 and 2022, five Bureau officers killed their partners or ex-partners. Two of the victims were themselves police officers. Five other men who were former officers also killed their partners during this period.

Table: Ana Claudia Chacin, David Newcomb Morales, Miami Herald, CPI

One of the victims, Yaritza Luciano Bonilla, was killed on March 24, 2013. She had a protection order against her husband, Pedro Juan López Maldonado, an officer assigned to Puerto Rico’s Rapid Action Joint Forces.

But Luciano Bonilla withdrew the complaint—common among survivors of domestic violence, according to legal advocates, experts, and rights activists. Experts say financial and emotional dependence, children in common, and family pressures are some of the reasons victims may decide to drop legal proceedings. Luciano Bonilla requested that her complaint be dismissed 10 days after her original request, according to the San Juan daily El Nuevo Día.

In Luciano Bonilla’s case, the Bureau took her husband’s service weapon away for several months, but returned it at the recommendation of the department’s psychology division. Three months later, López Maldonado killed his wife, then himself.

In July 2013, Puerto Rico’s government and the U.S. Justice Department signed the Puerto Rico Police Department Reform agreement after the federal agency’s investigation. Four other women have been killed by their police partners since the reforms began, even though in 2016 the Bureau established new protocols for handling domestic violence cases involving agency employees. In 2019, the agency issued a new order with that purpose.

The death of another woman, the wife of an officer in the Bayamón area, remains unsolved. Betsy Rodríguez Burgos, 39, burned to death in 2016 in a car that belonged to her husband, Daniel Soto Valentín. He was charged with her murder in 2020. However, a judge in the coastal town of Arecibo determined in a preliminary hearing that there was no probable cause to go to trial.

‘Don’t Let Me Die’

Brenda Liz Pérez Bahamonde, 46, was one of the most recent victims of an active police officer. She herself was an officer in the homicide division of the southeastern Guayama police region. She was murdered on January 27 this year.

That night her former partner, also a police officer, José Rivera Velázquez, went to her home in the coastal town of Salinas and shot her several times with his service weapon. Wounded, Pérez Bahamonde drove to the closest station and asked for help.

“Don’t let me die,” she told her fellow officers. In that brief exchange, she said Rivera Velázquez had shot her, according to local media the following day. She died that night.

Two months earlier, Pérez Bahamonde had requested an eviction order for Rivera Velázquez to leave the home they shared. She obtained a protection order and, as a result, the Bureau took away his service weapon.

During a hearing on December 1, 2021, Pérez Bahamonde withdrew the protection order. Six weeks later, a Bureau psychologist deemed Rivera Velázquez fit to carry his service weapon again—the same one he used to kill Pérez Bahamonde 17 days later.

Pérez Bahamonde was the mother of four children. The youngest, Nicole Colón Pérez, 24, said in an interview that Rivera Velázquez’s alcohol abuse was one of the reasons her mother wanted to end the relationship.

The young woman, who has lived in Boston for nearly five years, also knows that her mother did not want any contact with her former partner. She had blocked his calls, but he reached out over email.

“He told me himself, that he followed her every day, that he went to my mother’s work every day,” she said, “I think he planned it all and that his knowledge as a police officer helped him.”

She believes that a more rigorous psychological evaluation would have prevented the weapon from being returned to him so soon.

Rivera Velázquez was accused of femicide, a crime that, since August 2021, is first-degree murder in Puerto Rico and carries a 99-year sentence. He pleaded guilty in April to second-degree murder and firearm violations. He was sentenced to 60 years.

The police chief and his aides defended how they handled the complaint against Rivera Velázquez.

Likewise, Sgt. Ivette Rivera Velázquez (no relation to José Rivera Velázquez) said that as soon as the court issued the protection order, the officer was disarmed and investigated. The Bureau’s internal investigation, which included interviews with relatives and co-workers, concluded that he “was not aggressive.”

“Everything pointed to the fact that no one could prevent what happened next,” the sergeant said.

The same month Rivera Velázquez killed his former partner, the government’s Women’s Advocate Office launched an investigation on the Bureau’s management of domestic violence cases involving police officers, and information about Rivera Velázquez specifically.

“After several procedures, among which extensions, answers, and appeals to requirements were granted, the Bureau refused to produce and deliver all the information and documents required by the Women’s Advocate Office,” the interim advocate, Madeline Bermúdez, said at an October 28 hearing of the Women Affairs Commission of the Puerto Rico House of Representatives.

The Bureau’s refusal forced the Women’s Advocate Office to take the agency to court, where it has an active lawsuit over the information request. At the legislative hearing, Bureau representatives Miguel Candelario and Lt. Aymée Alvarado, among others, gave information about 423 administrative complaints filed against Bureau officers since 2017. But when legislators asked, they said that they did not have the required information, even though the agency had provided it a year earlier by court order for the Herald and CPI investigation.

The statement from Frente Unido Policías Organizados union —the one Figueroa Torres, who had made himself available as a “faithful collaborator” to deal with the problem, authored before killing his partner and himself— was expunged from the record by the legislative commission after the murder-suicide became public knowledge.

—

If you or someone you know is in a situation of domestic violence, call 787-489-0022 for guidance and help.