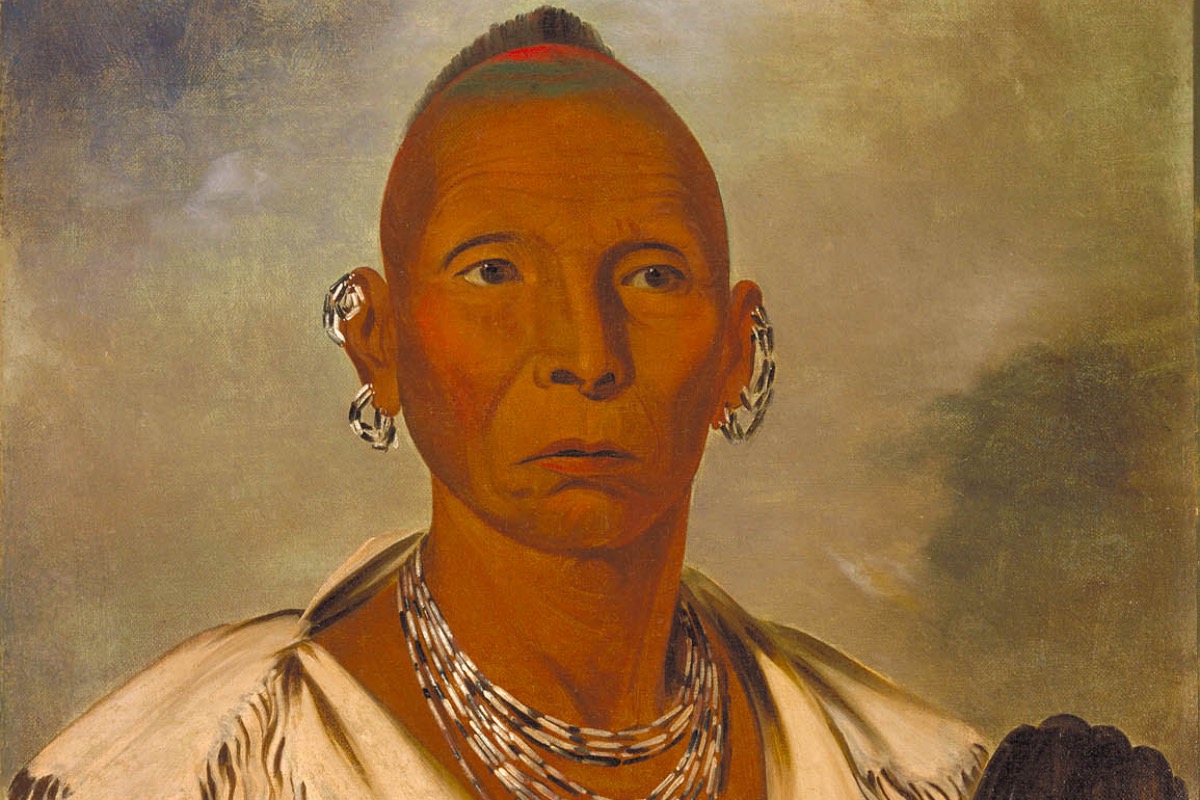

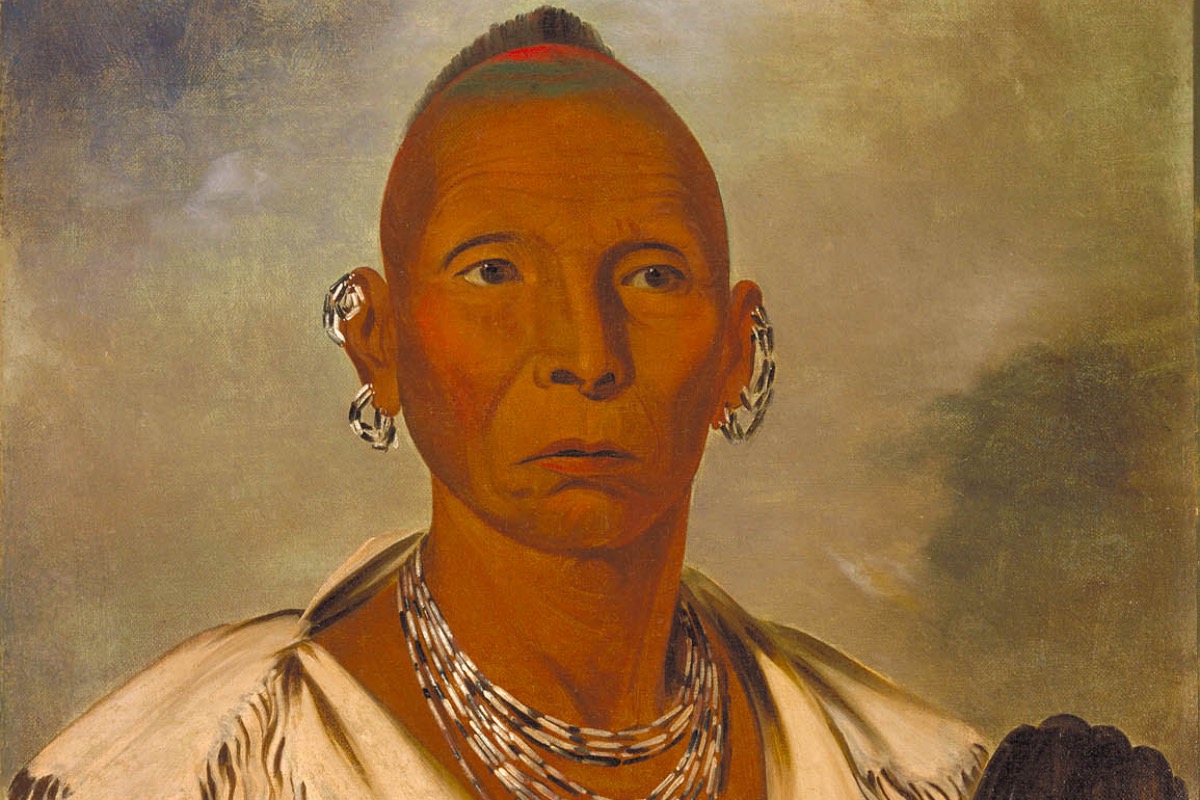

Portrait of Black Hawk, the Sauk war chief and namesake of the Black Hawk War, 1832 (Public Domain)

LAS VEGAS — One time, when I was a kid, we found an old rifle in the woods by where we lived in the suburbs of Chicago. I’ve told this story before, so apologies if you’re hearing it for the umpteenth time.

I grew up in the town of Prospect Heights from third grade through eighth, after my mom moved us there from the city. The street we lived on ended at Des Plaines River Road, which formed the boundary of a forest preserve called Allison Woods. When we had nothing to do and felt like exploring or fishing, my brother, our cousin and I would walk into the woods and spend hours in there.

We used to imagine we were Indians, or at least I did, as we walked softly on the narrow footpath that wound along the river, trying not to crunch any leaves or snap twigs so that we wouldn’t scare away any animals up ahead. If only I had real, deerskin moccasins, I always told myself…

Being in those woods, it was pretty easy picturing what the area must’ve been like when the first white guy built a cabin there in the early 1800s.

Even as kids we knew there had been Indians on the land before. There were references to them all over the place: Indian Trails Library, Lake Potawatomi, Algonquin Road, Kankakee, Wabash, the Blackhawks… Even names like Deerfield and Buffalo Grove had an Indian feel to them.

Being a nerd, I knew that Illinois got its name from the Illiniwek, which is how the French explorers translated what the locals called themselves, just like “Chicago” was the French version of shikaakwa, an Indian word for the wild onions that used to grow there.

There’s also something about a place with forests and rivers and creeks that, specifically in America, makes you think of Indians.

The old rifle we found had been hidden under leaves and far off the trail. No one but us kids would’ve stumbled on it in a thousand years, or at least until they cleared the trees to build a strip mall. We knew jack about guns at the time, and I hardly know much about them now, but thinking back on it and doing a bit of research, I’d say it was a Minié rifle. The ones on Wikipedia look exactly how I remember it, only the one we found had been in the woods and exposed to the elements for a long time, the barrel caked with dirt, the engravings on its silvery lockplate hardly readable. (I had to Google “anatomy of a rifle” to find the word lockplate.)

When we found the rifle I imagined a squirmish between white settlers and the local Natives on the very spot where we stood. Whether it’d been a white man carrying the rifle or an Indian, and what had caused whoever it was to drop it and leave it there, are what had my mind humming. I imagined the worst.

I realized then, and realize even more so now, that I owe my childhood —and, thus, a huge part of my identity, how I see and understand myself— to the white men who came to Illinois and forced the Indians out. After all, if it hadn’t been for their gradual invasion, who knows where I would’ve grown up or where and who I would be today? I wouldn’t have been born at all, if you think about it, considering my mom is a Honduran immigrant who met my father in Chicago, his parents having immigrated there from Puerto Rico in the ‘50s. If Chicago were still in Indian Territory, they never would’ve crossed paths.

Being the product of a genocidal war isn’t a happy feeling, but it comes with the territory when you’re an American, and especially Latino.

As a Chicagoan, though, and also a person with Indigenous and African blood, I also take it as a point of pride that the first Chicagoan, the first non-Native person, I mean, was a black man by the name of Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, whose name suggests he was either from French Canada, French Louisiana, or, most likely —and the theory I personally prefer— French Haiti.

Du Sable seems to have been a force of nature. Had he been a white man, his name would be honored today alongside Washington, Jefferson, Franklin, and Hamilton. As it stands, he’s barely mentioned in the city he helped get started.

The first mention of du Sable in written history is by a white man who stopped at his house and trading post on the Chicago River in 1790. Four years later, a Frenchman from Green Bay described du Sable as a big wealthy merchant.

The British commander of Fort Detroit during the American Revolution said du Sable was “a handsome negro… well educated… settled in Eschecagou.” Major DePeyster had at least heard of du Sable in 1779, when he received a report that du Sable, living at the time near the shore of Lake Michigan in Indiana, had been arrested under suspicion of supporting the Patriot cause, but was released after friends vouched for his character.

All of this goes to show how impressive du Sable must’ve been either way, being a black man that so many white people heard and even wrote about.

When du Sable sold his house in 1800, the bill of sale listed his property as:

“1 wooden house 40′ x 22′

1 horsemill 36′ x 24′

1 pair of millstones 2 1/2′

1 bakehouse 20′ x 18′

1 dairy 10′ square

1 smokehouse 8′ square

1 poultry-house 15′ square

1 workshop 15′ x 12′

1 stable 30′ x 24′

1 barn 40′ x 28’…

1 horse stable…

30 head of cattle full-grown

2 spring calves

38 hogs

2 mules

44 hens”

Not bad for a black man in America in the year 1800—or any year, for that matter.

Even more fascinating, du Sable married an Indian woman named Kitihawa in a Potawatomi ceremony, and the two eventually had a son named Jean and a daughter named Susanne. There’s even a rumor that du Sable had been hoping to become chief of the local Potawatomis and finally left Chicago for Missouri when the Indians refused his leadership.

Another early founder of Chicago, Antoine Ouilmette, a French Canadian fur trader, also married a Potawatomi woman, the daughter of Chief Naunongee, and they built their house right next to du Sable’s on the river. The chief’s other three daughters all married French Canadian fur traders too.

So Chicago’s roots are Indian, French, and Black, in that order. The English-speaking savages came later.

When I was a kid, I thought Chief Black Hawk was the local Indian leader when the white men came. His name and likeness are used for the city’s pro hockey team, of course, and the elementary school I went to is just off Blackhawk Street. Judging by the hockey logo, I assumed Chief Blackhawk —which is how I would’ve spelled his name then— was a fierce warrior who didn’t take any shit and fought the white settlers to the death, which explained why they use his name to this day. Americans don’t revere the names of great Indian warriors and leaders as much as they lionize them to confirm their own superiority, as if to say, “Look at this powerful Indian and his people that we completely annihilated.”

They used to display the heads of rebel leaders on pikes for the same reason, like they did William Wallace. Now, in America, they put the heads on jerseys.

The military uses Indian names and words almost like talismans: Blackhawk, Apache and Chinook helicopters, Tomahawk missiles, “Operation Geronimo,” which took out Osama bin Laden…

“Why do we name our battles and weapons after people we have vanquished?” asks Simon Waxman in the Washington Post. “For the same reason the Washington team is the Redskins and my hometown Red Sox go to Cleveland to play the Indians and to Atlanta to play the Braves: because the myth of the worthy native adversary is more palatable than the reality—the conquered tribes of this land were not rivals but victims, cheated and impossibly outgunned.”

There’s more juicy bits in that op-ed, so go read it after you’re done here.

Anyway, turns out Chief Black Hawk’s territory was way west of Chicago, and after losing a war named for him in 1833 —the same year Chicago was first incorporated as a town— he died defeated and heartbroken a few years later in Iowa.

As for the rifle we found in the woods that day, we chucked it around to see if it would go off. After deeming it safe to carry, we brought it back to our apartment, walking down the street with it in broad daylight. I’m sure the drivers and anyone else who saw us figured we were carrying a big stick and only pretending it was a rifle.

We showed the thing to my mom, who had been in the Navy, and she yelled at us and told us to throw it away. We begged her to let us keep it, telling her it was probably really old and might fetch a pretty penny on Antiques Roadshow or something, but she wasn’t having it. So we just tossed it down the garbage chute.

I still wonder about it though.

***

Hector Luis Alamo is the Senior Editor at Latino Rebels and hosts the Latin[ish] podcast. Twitter: @HectorLuisAlamo