‘The Lady of Silence: The Mataviejitas Murders’ (Courtesy of Netflix)

Between October 1984 and November 1987, Thierry Paulin, a Martinique-born French citizen, murdered 18 elderly women. The motive? Robbery. The method? Some were suffocated, their heads stuck in paper bags; others were beaten to death, and one was forced to drink drain cleaner.

He was known as “The Monster of Montmartre,” “The Grim Reaper of Paris” and, more blandly, “The Old Lady Killer.” So when Mexican authorities were faced with their own mataviejitas near the end of the last century, they asked that the French detectives in charge of the Paulin case train them in the proper procedures for tracking down and stopping a serial killer—the first case of its kind in Mexican history.

This is one of the many wonderful tidbits included in María José Cuevas’ fascinating and gripping new documentary, The Lady of Silence: The Mataviejitas Murders, now streaming on Netflix.

From 1998 to 2005, 49 elderly women were robbed and strangled in their homes by a serial killer dubbed the “Mataviejitas” (The Little Old Lady Killer), once law enforcement agencies reluctantly acknowledged his or her existence—well, mostly his, because as far as they were concerned, only men were serial killers.

What Cuevas does so masterfully is go beyond a simple Wikipedia entry by interviewing the relatives of the victims, the attorneys, and police officers involved in the investigation, and looking at those external forces and procedures —not to mention myths— that have a bearing on or provide context to this story.

All of the victims were women older than 60, and all the authorities knew was that someone was impersonating a social worker to gain a victim’s confidence in order to enter her home, rob, and kill her. Criminologist Patricia Payán was told to stop watching movies when she raised the possibility that there was something more to these crimes than a mere robbery that ended violently.

The first murders took place in Coyoacán in Mexico City, but increased in number across Mexico City in the early aughts. By this time, Mexico City’s mayor at the time and the current president, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, had implemented a series of social programs that helped the most vulnerable, especially the elderly, providing the killer with a motive for approaching victims.

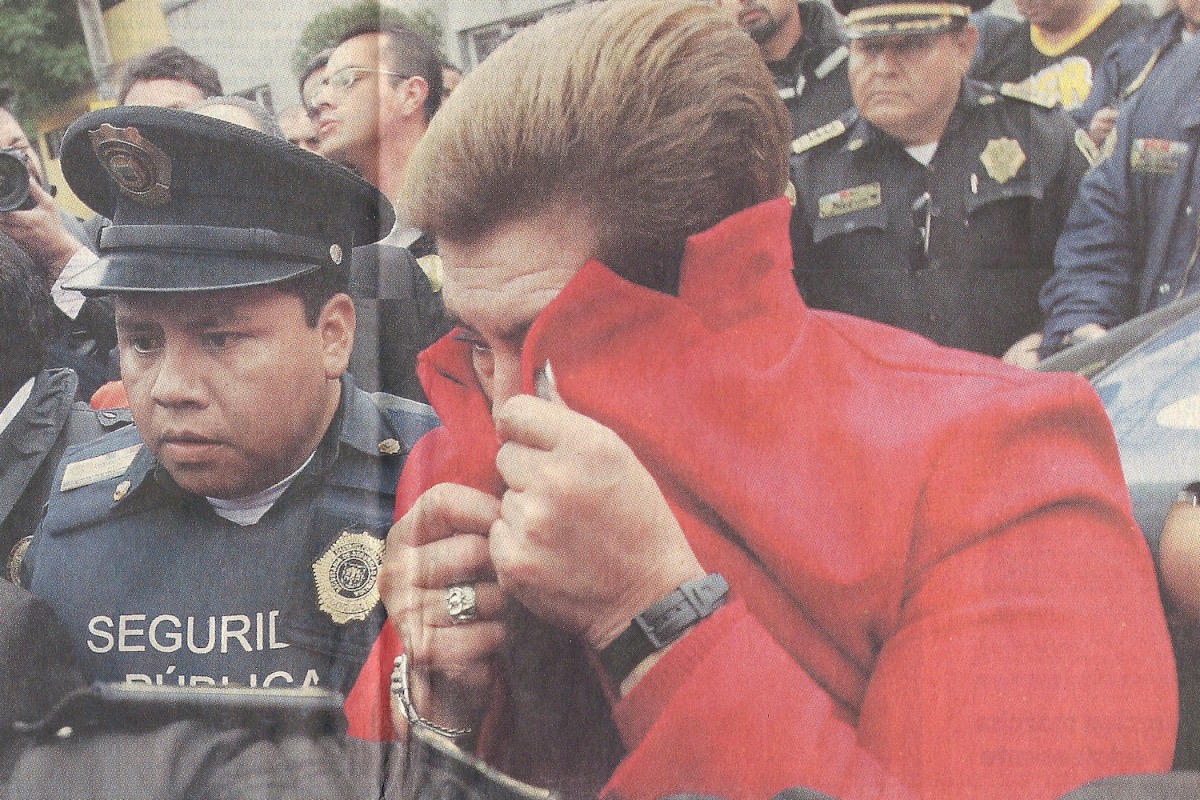

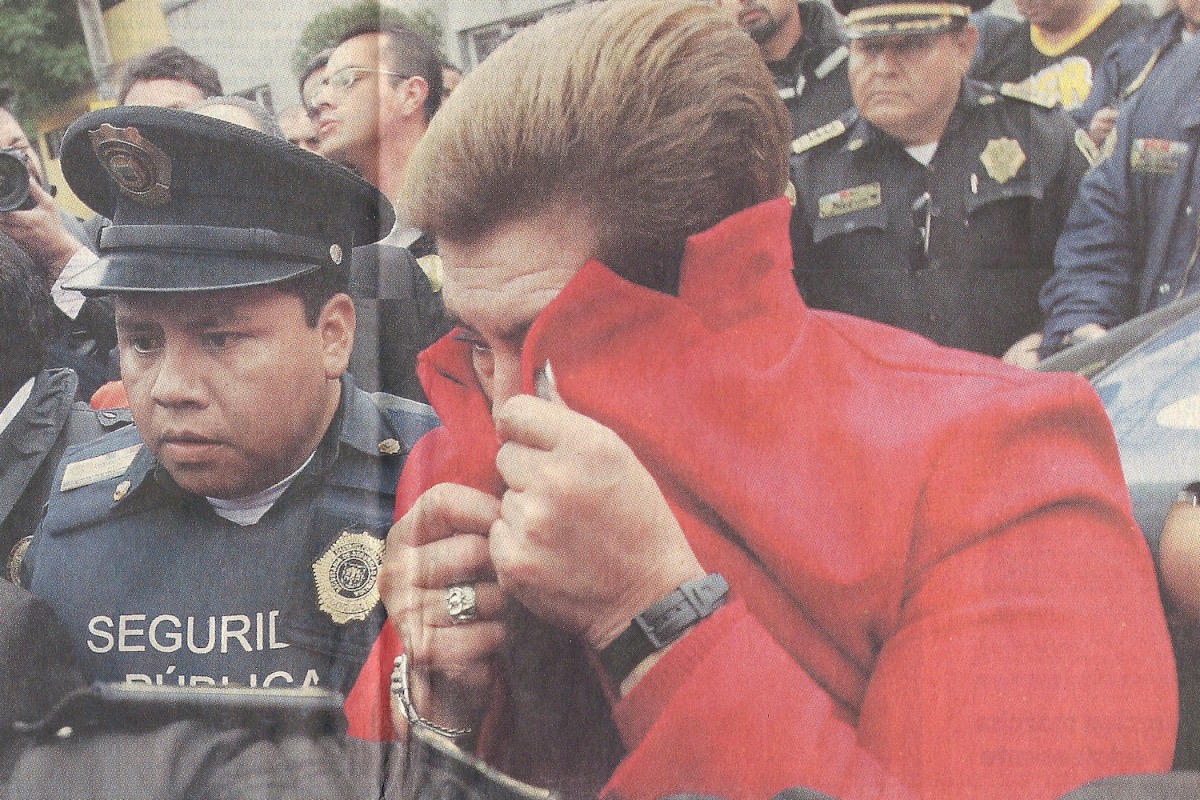

Witness descriptions of the assailant were scattered. The media picked up on the case and plastered the front page and headlined their newscasts with the latest developments and gruesome details. Two suspects, Araceli Vázquez and Mario Tablas, were arrested and accused of being the killer, paraded in front of reporters. One prosecutor summed up the method succinctly: “detain to investigate instead of investigating and then detain”—something akin to shooting first and asking questions later, a police practice that continues in Mexico to this day.

With two suspects in custody, the mataviejitas kept killing and questions piled up. Was Mexico’s attorney general and police investigators dealing with a copycat killer?

A nurse, Matilde Sánchez Gallego, was arrested as she left work, since, according to authorities, her description matched that of the serial killer. But when her colleagues protested in front of the prison where she was being held and her fingerprints proved to be no match to one found at the scene of a crime, Matilde was let go.

Cuevas looks at the many prejudices surrounding the investigation, starting with the contemptuous dismissal of the criminologist, Payán. She questions the mythical role of the abuelita in Mexican —and, for that matter, Latin American— culture and the idea that old ladies are selfless women whose mission is to provide comfort and wisdom to the patriarchy. Who would dare kill the most defenseless? Then, there’s the whole homophobic and even transphobic direction the case took, as investigators believed that a transvestite might be the killer. Finally, why did the media take these serial killings far more seriously than the femicides taking place around the same time in Ciudad Juárez and even others in Mexico City?

The case takes a final bizarre twist when the Mataviejitas is actually arrested after killing her final victim. The killer turns out to be one Juana Barraza, a woman with a sad background full of abuse who became a professional wrestler (or did she?) under the name of “La dama del silencio“ (The Lady of Silence).

The final 10 minutes of the documentary are devoted to her so-called wrestling career, but no major insights are drawn from this, except that it underlines the fact that, unlike most fiction shows and novels about police procedurals, it is usually the most serendipitous of circumstances that lead to a crime being solved—and that most serial killers are, in the end, broken, mundane figures, not the über-intellectuals with high IQs that seem to predominate the horror genre.

Although Cuevas’ documentary does give voice to the victims’ relatives, the peculiarity of the case and the ineffectiveness of a police force tied to old ways of doing things overwhelm this tragedy. These victims are just names and ages in the film; we only get a glimpse of who they were from their relatives, but never enough to feel the weight of their loss. If anything, one can say that in sticking to the details of the investigation, the ups and downs, the mistakes made, the social and political forces the investigators faced, and the times they lived in, The Lady of Silence: The Mataviejitas Murders sticks close to the traditional true-crime documentary—so much in fact that, outside of some newsreels and video footage, the so-called “Lady of Silence” lives up to her name. We don’t know enough about her or whether her life story is true or something she concocted.

Like John Wayne Gacy and Jack the Ripper before her, Barraza’s story still fascinates, satiating our appetite for the lurid and the violent, much like many of the true-crime stories we feed on. Add to this a look into how the police and attorney generals of a different country operate, and you end up with a disturbing but thoroughly satisfying film.

***

Alejandro A. Riera is a film critic and the media coordinator for several music and film festivals in Chicago where he lives. He has been writing about film and television since 1993, when he joined the team of ¡Exito!, the Chicago Tribune’s Spanish-language weekly. He is a member and treasurer of the Chicago Film Critics Association and a rabid defender of Latin American cinema. Twitter: @AlejandroARiera