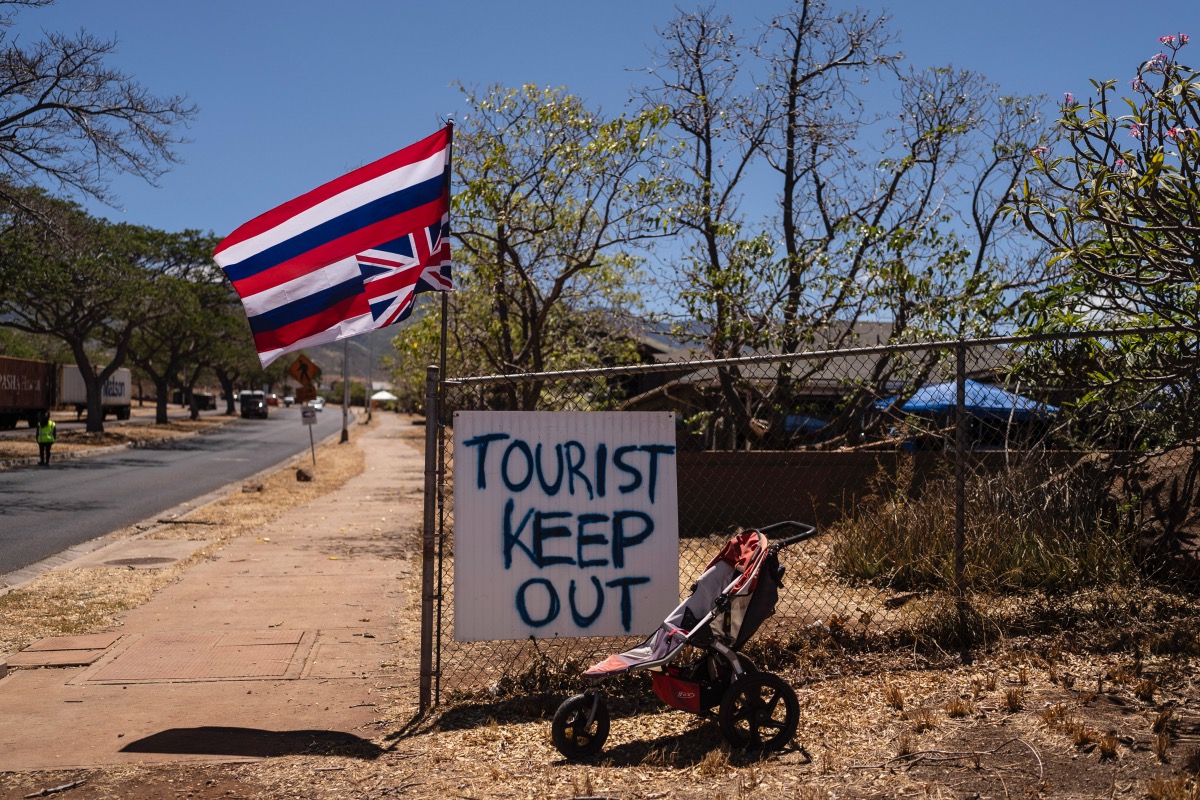

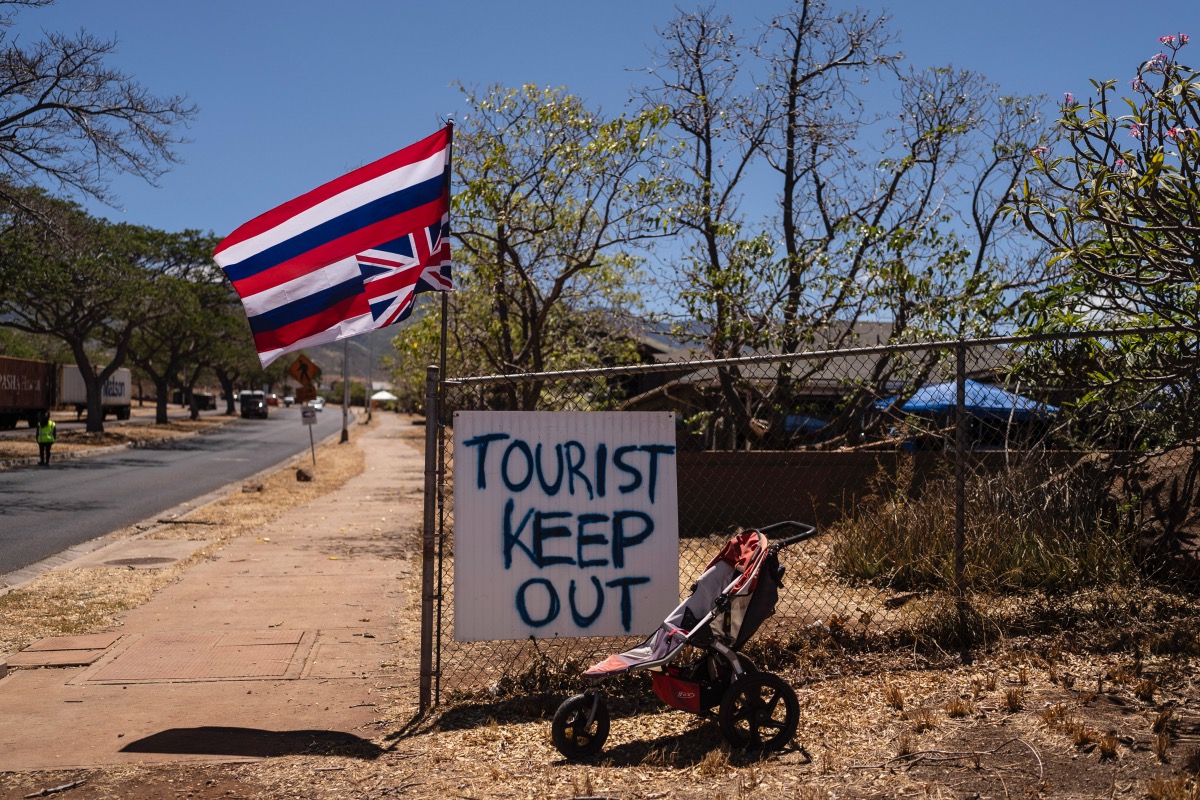

A sign that says “Tourist Keep Out” is seen next to a Hawaiian flag hanging upside down in Lahaina, Hawaii, Thursday, August 17, 2023. Long before a wildfire blasted through the island of Maui the week before, there was tension between Hawaii’s longtime residents and the visitors some islanders resent for turning their beaches, mountains and communities into playgrounds. But that tension is building in the aftermath of the deadliest U.S. wildfire in more than a century. (AP Photo/Jae C. Hong)

“Tourist keep out“… “Let Maui heal”… “Lahaina is not for sale.”

As I watched TV coverage of the wildfires incinerating Maui, the ancestral land of the Hawaiian Kingdom, overthrown by the United States in a coup, a single thought raged in my head: Colonialism is a brutal, never-ending story.

The footage triggered memories of Hurricane María, which devastated Puerto Rico in 2017 and transformed the archipelago into a rich man’s paradise—and a no man’s land for many Puerto Ricans.

The harrowing images tell the story of over a century of sugar barons, the theft of land and water, government neglect, and the marginalization of a people in their native homeland. But the fires also uncovered a reality that should slap Puerto Ricans awake: Even with statehood, Native Hawaiians have been ghettoized on their own land.

It’s hard listening to Native Hawaiians —or Kānaka Maoli— plead with real estate predators not to call families who have lost everything, because I know how futile that is.

“It is disgusting. We have real estate investors and speculators going around calling our victims, offering them to give them cash and buy their property,” Maui resident Tiare Lawrence told NBC News. “We will do whatever it takes to protect Lahaina. We have already been displaced enough.”

Hawaii Gov. Josh Green (D) promised to prevent “land grabs“ and protect Native Hawaiians from speculators after the fires burned down entire communities in early August.

President Joe Biden, set to visit Maui on Monday, is expected to promise much the same. Hopefully he will do better than his predecessor, Donald Trump, who lobbed paper towels at Puerto Ricans after María ravaged the island in 2017 and left almost 3,000 people dead and $90 billion in damages.

The destruction on Maui is apocalyptic. The fires torched almost 3,000 structures. More than 850 people, many of them children, are still missing, and the official number of dead stands at 114 but will likely increase. It will be months before the cause of the fires is known, although downed power lines and decisions made by utility company Hawaiian Electric are being investigated.

Yet, what is happening in Maui is more than a catastrophic natural disaster. It is a perfect example of disaster capitalism, a repeat of Puerto Rico where a tax evader’s paradise now masks an island in crisis and the displacement of Puerto Ricans.

After María brought the island to its knees, the governing pro-statehood New Progressive Party opened it up to real estate predators, crypto bros and the ultra-rich through Act 60, which has led to Puerto Ricans being pushed out of their homes and the island.

The law attracted the likes of wealth manager Kira Golden, who recently said in an interview that Hurricane María was “amazing for the island,” and Kenneth Chesebro, a Harvard-trained lawyer known as the “brains” behind Trump’s fake voters and singled out in the recent Georgia indictments.

Tax cheats are taking over Puerto Rico. It's Tax Day, tell Congress to #EndAct22 today! Check out this video from our friends @LosingPuertoRico. Learn more at https://t.co/81lSB32Vjn #NotYourTaxHaven pic.twitter.com/T4AdkAzPwr

— Power4PuertoRico (@Pwr4PuertoRico) April 18, 2023

“The fire that affected Hawaii recently and has led to displacement reminds us of recent displacements in Puerto Rico,” Puerto Rican environmentalist, philanthropist and community leader Amaury Rivera told Latino Rebels. “We have not been subject to fires but to something similar. Our fire accelerant has been a combination of greed, corruption, and incompetence, resulting in massive migration.”

Hawaii and Puerto Rico have much in common even though one is a state and the other a colony. Both were taken by force by the U.S. in the 1890s. Both suffer the historical trauma of colonization (and the Jones Act), and both must live with death and loss under a steady influx of tourists.

And, just as there are two Puerto Ricos, there are two Mauis—one for the mega-rich and another for the native population, most of whom work low-paying jobs, largely in tourism.

And the displacement is absolute.

María caused the forced exile of at least 130,000 Puerto Ricans, nearly five percent of the island’s population. It’s estimated that between 114,000 and 213,000 residents leave Puerto Rico every year due to the devastation wrought by recent natural disasters and the subsequent gentrification.

As of 2021, more Native Hawaiians lived on the mainland than on the islands. Some 310,000 Native Hawaiians live on the Hawaiian Islands compared to 370,000 living in the continental United States, according to the American Community Survey.

Nuria Sebazco, a veteran Puerto Rican journalist and TV news anchor who covered the devastation of Hurricane María, told Latino Rebels that Maui “serves as an example of what the righting power of nature is capable of.”

“It unveils the worrisome impact of an economic system that favors the wealthy, making the locals vulnerable and forced to struggle in their own land, which is gradually being owned by others,” she said.

Puerto Rico is presently addressing its colonial status. In 2022 the U.S. House of Representatives passed the Puerto Rico Status Act, a bill that calls for a federally binding referendum scheduled for November 2025, in which Puerto Ricans would choose between one of three non-colonial options: statehood, independence or free association with the U.S.

Some Puerto Ricans who advocate statehood scoff at the argument that Puerto Ricans are being displaced and insist that Native Hawaiians aren’t being displaced either. But they dare not acknowledge that Kānaka Maoli, even though Hawaii is a state, are third-class citizens in their own country. And the same will happen to Puerto Ricans if the islands become a state.

In a recent interview with PopSugar, Blue Beetle’s Puerto Rican director, Angel Manuel Soto, spoke about gentrification and colonialism, themes he addresses in the movie.

“We were having a conversation about what gentrification looks like. They push you away until they want that place,” he said. “Then they keep pushing you away and keep pushing you away and keep pushing away until you cease to exist. We wanted to communicate that in a way that resonates with my personal experience —[Puerto Rico’s] collective experience— but I think in general, the collective experience of Latin America.”

It’s also Hawaii’s collective experience.

Statehood didn’t bring equality to the Kānaka Maoli, and it will not bring equality to Boricuas either.

If Puerto Rico doesn’t wake up to this fact, history will inevitably repeat itself. We have to listen to calls for sovereignty, which grow louder. But we must act fast before time runs out.

***

Susanne Ramirez de Arellano is the former News Director for Univision Puerto Rico and a writer and journalist living between San Juan and New York City. Comments can be sent to her email. Twitter: @DurgaOne

Susanne Ramirez de Arellano is the former News Director for Univision Puerto Rico and a writer and journalist living between San Juan and New York City. Comments can be sent to her email. Twitter: @DurgaOne

Awesome. Keep democrats like Oprah and Bill Gates the hell out of the Lahaina valley.

Dearest Susanne, I find it somewhat comical that you do not see the hypocrisy of your position. On the one hand, you seem to feel that the United States should have “open borders” and allow unimpeded access to anyone wanting to enter. But, on the other hand, you think it is proper to establish your own borders to “keep out tourists” or foreign investors. Why is it okay for Puerto Rico and Hawaii to “keep out” undesirables, but it is not okay for the people along the southern border of the United States to do the same? The citizens of the United States feel exactly the same way you do: They resent “outsiders” exploiting the public, taxpayer-funded resources to which they have no lawful claim. Even the Mayor of New York City, a liberal Democrat, has said “enough is enough” illegal immigration. Respectfully, Stefano