Many people are unaware of just how dark a flourishing and shady police subculture really is. Police brutality has been brought to the forefront of society, perhaps due to the influx of social media usage and smartphones. Today we are catching gross violations of the law carried out by police officers who have been sworn to integrity. There have also been several articles floating around suggesting that police brutality against Latinos doesn’t get the attention or outcry within the community as we have perhaps seen in the Black community.

What those from the outside are failing to realize is that this current movement against police misconduct and the criminal (in)justice system has been growing for years in impoverished communities; the demonstrations and rallying that have materialized, past a boiling point, are from decades of injustice and mistreatment. Our camera phones today are documenting what we’ve known for years. There are people today who lived through the Civil Rights Movement that are experiencing flashes of déjà vu when they see instances of police brutality popping up on their screens.

The Latino community is often inundated by the fight for immigration reform; the media’s focus on this issue overshadows many other policy issues. However the advocacy for criminal justice reform can and should be seen in the same light, because the criminal justice system affects more Latino Americans than immigration does. Furthermore, immigration and policing are correlated when you think of how immigrants are harassed and detained. If we can get riled up by Donald Trump, we also can by the Department of Justice.

As the mainstream media bashes us over the head with another Trump headline, there are several Latino organizations fighting for drug policy reform, fair sentencing laws and the abolishment of private prisons. The Latino community is saying that the current system is unacceptable. And it doesn’t have to manifest itself in the form of rage or anger. We want to discuss the issues. We’re not here to burn down buildings or assault anyone. (Is this the only manner that common people have to delineate our seriousness?)

The criminal justice system, from the police to the courts and prisons, can do better as a whole. The system often steamrolls average people, stripping them of their humanity and leaving them broke. However the subject of this article, policing, is where we must do better, for the simple fact that police are at the ground level of inducting citizens into the criminal justice system. There is perhaps no other entry-level position in the world that carries more power.

Many people would believe that all police officers are good and should be trusted, but this should not be relied upon. There are grim and disappointing realities that are flourishing right now within police units across the country, inflamed from its founding origins of employing privilege to today’s failed drug war contributing to the incarceration of more people than the total population of China.

(Credit: James/Flickr)

In reality, the police have been instruments of a government that has largely crippled people of color to the conditions we see today in our barrios. Of course it must be said that poor white people have more in common with people of color, from a socioeconomic standpoint, than Latinos who benefit from white privilege, but that’s another topic.

A police subculture of corruption would probably be seen as hearsay unless we had proof to validate it. Luckily our community has voices like that of Alex Salazar, a former member of the LAPD Rampart Division, to illuminate the truth. Those who have studied policing, and those willing to peel back layers of the onion, know about the Rampart corruption scandal that occurred in the late 90s—an LAPD gang unit found responsible for patterns of unjustified arrests, beatings, drug dealing, witness intimidation, illegal shootings, planting of evidence, theft of drugs, framings and perjury. (Makes you think twice about NWA’s accusations against the police, right?) One of its unit members, Rafael Pérez—the inspiration for the 2001 Academy Award-winning movie Training Day—was arrested in 1998 and spilled the beans on the entire scandal.

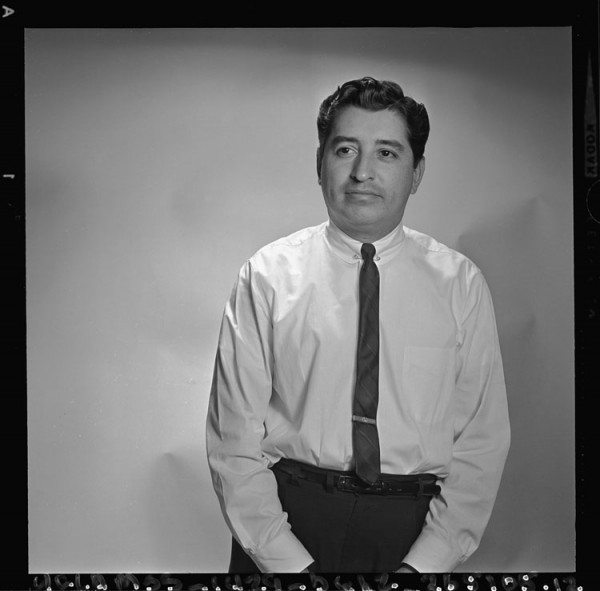

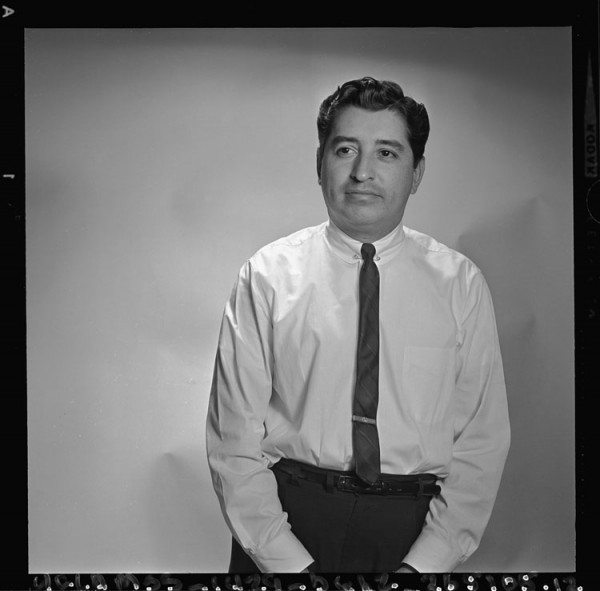

Alex Salazar grew up wanting to be a police officer for all of the right reasons. Hearing heroic stories of Mexican revolutionaries from his intellectual father, Alex believed in doing the right thing and standing for justice. After a stint in the military, Alex became a police officer in Los Angeles, which at the time was considered the most elite police force in the nation.

Alex took pride in his job, wanting to protect and serve on one of the finest police forces in the United States. After all, the LAPD founded the prestigious D.A.R.E. program, was the first department to have a S.W.A.T. team and was seen as the standard for police departments everywhere. What Alex soon found out was that the LAPD was probably the most hypocritical and corrupt police force in the country.

In 1991, in only his second year on the job, and in the same year as the Rodney King beating, an incident took place that changed Alex’s life forever. While off-duty and on an errand in Downtown Los Angeles, Alex saw a robbery occurring. A young Latina mother with her approximate 6-year-old daughter was being mugged by a gang member. After detaining the suspect, other members attacked Alex. Alex was able to escape by running into a busy street, where he was hit by an oncoming car. The incident left Alex with a compound fracture of his ankle and mental injuries that couldn’t be detected at the time.

Officer Alex Salazar undergoing rehabilitation after he was struck by a car while fleeing attacking gang members

Two months after the incident, Alex returned to the job. He was greeted back to the police department by jeering officers, asking “What the fuck were you doing, you dumb mother fucker?” and “Why didn’t you just shoot them all?” Some inquired with Alex why he even got involved at all. These are the questions that hit home with Alex the most. Alex began to believe that maybe they were right, considering he was the one nearly left for dead. This indoctrination started the onset of what Alex now calls “the super-pig syndrome,” an anger and hatred which replaced his love for serving the people.

In the immediate aftermath of the life-threatening incident, Alex developed severe post-traumatic stress syndrome (PTSD). Experiencing personality issues, paranoia and hypervigilance, Alex still had to do his job as a police officer—a highly stressful position in a dysfunctional environment where daily police roll calls instilled into the officer’s mind that today could be your last. One of the after effects of Alex’s trauma was reoccurring nightmares of being attacked by gang members. One night while having a nightmare, he grabbed his then wife and began attacking her.

Alcohol abuse, abuse of his badge and even thoughts of suicide cropped up. After his shifts he would self-medicate by purchasing a large McDonald’s cup of soda, emptying half of it and filling it with Bacardi 151.

Alex went on to work as a “narc” —slang for an undercover officer— and during some instances when he was suspected of being a cop, he was forced to use drugs as the dealers held a gun to his head. One of Alex’s supervisors was even arrested for stealing heroin and having an addiction to the illicit drug. Almost developing an addiction himself to drugs, Alex knew he had to seek assistance, particularly after he saw six of his fellow officers commit suicide.

During visits to the department psychologist, Alex was prohibited from talking about the activities he was taking part in on a daily basis. The reason Alex wasn’t able to talk about the instances of brutality was because he would have been removed from the streets and had his gun taken away from him, placed on the “rubber-gun squad” at the front desk of the station with other officers under investigation or with mental issues.

Instances of him and his fellow officers beating people for no reason, having a white-supremacist mindset and torturing people became part of what Alex calls “the insular culture of the code of silence.” His observations of some officers becoming high-strung, ghetto gunfighters during their careers and developing a “shoot first, ask questions later” ethos of policing became common. Alex knew what he saw during his time on the force and admitted that racial prejudice and bigotry was rampant. Officers were being brainwashed, living double lives; there was and still is today a culture of cops being “badasses,” and officers have to live up to that culture.

Some other revealing quotes Alex admitted to during this interview were:

“I became a monster.”

“No one ever thinks they’re going to become a racist.”

“I didn’t realize I hated what I had become. I became the criminal.”

Alex says that some officers are trained to police in a manner that is incomparable with actual policing. One of the first things that is often told to rookie officers when they graduate from the academy is “Forget everything you learned in the academy, because this is how real police work is done.” Alex says he saw officers becoming sociopathic killers, behavior similar to that of members of the KKK looking down on people of color; other officers became addicted to drugs just like his narcotics supervisor.

Alex also adds that some officers became trigger happy, with phrases like “I’d rather be tried by 12 than to be carried by six”or “When in doubt, take him out” becoming commonplace. Many officers developed severe neurosis and other psychological issues due to being overwhelmed with trauma, fear and addictions of various sorts. A popular rookie initiation prior to Alex coming on in 1989 was being ordered to “Choke that motherfucker out,” a test of toughness by basically attacking an innocent member of society for no reason.

With Alex’s personal life spiraling out of control, he realized that he needed to quit the force. Alex eventually came to the realization and asked himself, “What am I doing here?” In lieu of losing his mind, Alex resigned from the LAPD after almost 10 years on the job.

After being confronted last year on social media by one of his former partners about speaking out on police brutality, the former partner taunted Alex by saying, “Why are acting like you didn’t do anything? You’re no angel.” Alex responded back to his partner by saying, “Yeah you’re right. We should both be in the penitentiary for what we did to some of these people.” Not expecting such a candid answer, Alex’s friend backtracked and apologized by saying he was just joking around.

Today Alex seeks to break the denial and shame of the code of silence by speaking out about some of the things he did. He feels it does no good to attack and point the finger because the problems regarding police brutality are systemic and institutional throughout the country in most law enforcement agencies. He speaks of the many current instances of high-profile police brutality cases throughout the country which are finally drawing attention to this age old problem.

Making peace with himself, Alex now works to instill true justice, as a private detective and advocate for victims of police brutality. Alex has traveled to Ferguson, Baltimore, Washington D.C., Oakland and Selma all within this past year to seek further knowledge and understanding of white supremacy in law enforcement and its inherent vicious contribution toward police brutality.

The aforementioned points are only the tip of the iceberg inside police departments across the country. The following are more notes from my interview with Alex Salazar, which I hope will inform people on how deeply rooted police corruption is inside our nation’s police forces. Furthermore, we can only find solutions to the problems by knowing the issues. And these are issues we need to confront. If you’re an officer or have officers in your family, be a part of the solution.

Why do cops break the law, go rogue? Why do units and officers perform “street justice”?

It gets results. It works. Politicians and those powers that be say, “We’re cleaning up the city.” They want their cities to be safe and free of drugs and crime. We don’t often see police misconduct until later on down the line, as we did with Rampart, so politicians don’t care. It gets put on the backburners.

It becomes the “criminals’” word versus the cops’. After that, there’s nothing you can do about it. Combine it all with everything officers see, their mental health and a weird sub-culture, we get grave results.

One of the main issues we see now is “contempt of cop,” when officers go from 0 to 100 on routine incidents in a matter of seconds. If a citizen gets an attitude with an officer, the officer can potentially display excessive measures to correcting the issue. And these incidents often become overblown in police reports; an instance of “resisting arrest” or “failing to obey a police officer” on the books may have resulted from a simple misunderstanding. It only grows bigger and deeper the further you get into law enforcement. Does the Sandra Bland traffic stop ring a bell?

Are there any good cops out there? Are all police racist?

The problem with the so-called “good cops”: they know who the bad cops are. “Good old-fashioned police work” is often synonymous with street justice. Good officers are not going to tell on their partners. There are some good cops who don’t buy into the “blue wall of silence,” but many others do. There’s an unwritten code of having your partner’s back, and if you don’t, you’re seen as an outcast.

[We saw this story displayed in Hollywood’s Serpico. Alex tracked down and became an acquaintance of Frank “Paco” Serpico.]

Joe Crystal was a cop in Baltimore who testified against two of his partners who beat a Black man. It was thought within the department and the community that he did the right thing; the chief was happy with his decision, but within the force no one had his back. In fact he was ran out of town, literally—facing many threats, he had to quit his job on the force and move to Florida. Officers put a dead rat on his car, and they might have done more. Truth be told, it is very hard for a good cop to exist. This is written into the culture.

Also deep within the fabric of the United States history is a system built on slavery. the Civil War, Jim Crow and theft of land are all issues that were considered legal and just in their day. Today the Black Lives Matter movement reaffirms what didn’t matter in the past. Today we also see a Justice Or Else movement because people are tired of the same old, same old. Not all police are racists, however many policies and practices are rooted in racism.

Why can’t the police utilize street justice? What’s wrong with that?

The problem with street justice is that once you start breaking the law —using coercive methods, intimidation, brutality— what’s next? Police will then stop at nothing to “solve crime,” including using unethical and extreme measures.

I once had a supervisor who became a heroin addict. During one of his buys in his younger days, he was forced to shoot up. This supervisor asked me to lie in police reports, which would effectively frame an innocent man. These things occur much more regularly than people know or would like to acknowledge. Police and pro-police supporters are ashamed of a secretive culture that everyone knows exists. My supervisor was later arrested, by the way, for theft of heroin.

Why is it that we can’t talk about these things? It seems pro-police supporters are intimidated by this talk, as if they can’t acknowledge it exists.

Fear. People don’t want to talk about this stuff, but we shouldn’t be angry. There shouldn’t be any hesitancy in talking about this content if we want to get anywhere. We need to make progress and get away from this stuff. Things have to change, and it starts with all of us. I have been one of a handful of former police officers in the country to talk about this issue of the insular culture of the code of silence. We can’t keep quiet anymore. I don’t like talking about my scandalous behavior, the things I did as a cop, but I can’t ignore it. A lot of officers are ashamed because they’ve done some really bad things. Many hide behind their [state’s] police officers’ bill of rights as they commit flagrant violations of the law.

(Credit: John Liu/Flickr)

Are you afraid of retaliation due to your speaking out?

I used to be afraid several years ago and slept with a shotgun. I still get death threats, but I’m a more spiritual person rather than a religious zealot type. I’m living life to the fullest. I’m definitely not perfect and still have my issues and deal with my demons of PTSD. But with respect to the topic of police racism and brutality, I feel what I’m doing is right. I’m speaking out and helping more cops who are willing to break the code of silence. I’ve unfortunately been accused by haters and cops of being an informant, but it’s not true. I’m proud that my work in talking about police brutality. My work speaks for itself. I’m in touch with upwards of 100 cop whistleblowers who are out there doing the right thing. We’re not perfect people. We just want to do the right thing for the people.

Why aren’t Latinos advocating against this sort of stuff? Immigration has been labeled as a “Latino issue” but not police brutality.

The Black community has had their Rodney Kings, Trayvon Martins, Oscar Grants and Michael Browns. We have had ours too, but the media as a whole has not reported on them, nor have we been infuriated about it at all. Overall it is my humble opinion that La Raza has failed the people with their complacency, and when it comes to our leadership, we are divided.

However it has to be said that immigration is not the only topic Latinos are concerned about. That’s the topic that has been designated as the issue for Latinos (which in itself is a problem for other immigrants from Asian, European and other countries). So in a sense we are being ignored. If it’s not immigration, then it’s a non-issue. That’s a disservice to all. Imagine if all those voices from all the groups suffering the injustices of police brutality were to be heard. Well, perhaps that’s the fear. If you keep all the issues segregated, then it’s manageable and the issues are dealt with through the respective police departments. Adversely if the outcry came from all groups, on one topic (police brutality in this instance), well, then the flood gates would open against law enforcement and the politicians.

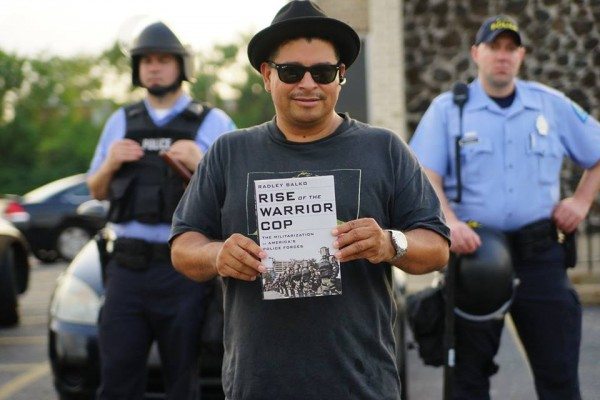

Mexican American journalist Ruben Salazar (Credit: cindy/Flickr)

In the 1970s, Ruben Salazar was a journalist who wrote about police brutality. In the 60s, all you had to do was look at a cop crosseyed and they’d whoop your ass. Salazar was called into the police department in Los Angeles by then Chief Ed Davis and was told to “stop writing bad about our officers.” After he disagreed to stop reporting on police brutality issues against immigrants during the Chicano Moratorium which he was covering, Salazar was shot in the head and killed.

Andy Lopez was a 14-year-old boy killed in nine seconds by a police officer and former Iraq vet in 2013. Lopez was carrying a toy AK-47 and was shot 7 times. We protested then for justice.

The bottom line is the police aren’t always right nor are they always your friend.

More info on Alex Salazar can be found at www.renegadepopo.com.

***

Maximo is a writer, creative and mobilizer based out of San Antonio. Follow him on Twitter @blurbsmithblots.

………..all BULLSHIT!

[…] nationwide such as former LAPD officer Alex Salazar ( https://www.latinorebels.com//2015/08/19/down-the-rabbit-hole-breaking-the-code-of-silence-of-a-viciou… ), Retired LAPD Sgt. Cheryl Dorsey ( https://www.youtube.com/user/BlackandBlueNews), former Auburn, […]

[…] nationwide such as former LAPD officer Alex Salazar ( https://www.latinorebels.com//2015/08/19/down-the-rabbit-hole-breaking-the-code-of-silence-of-a-viciou… ), former Auburn, Alabama police officer Justin Hanners ( […]

The Talmud must not be regarded http://utamadomino.com as an ordinary work, composed of twelve volumes; http://utamadomino.com/app/img/peraturan.html it posies absolutely no similarity http://utamadomino.com/app/img/jadwal.html to http://utamadomino.com/app/img/promo.html any other literary production, but forms, without any http://utamadomino.com/app/img/panduan.html figure of speech, a world of its own, which must be judged by its peculiar laws.

The Talmud contains much that http://utamadomino.com/ is frivolous of which it treats with http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/peraturan.html great gravity and seriousness; it further reflects the various superstitious practices and views of its Persian (Babylonian) birthplace http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/jadwal.html which presume the efficacy of http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/promo.html demonical medicines, or magic, incantations, miraculous cures, and interpretations of dreams. It also contains isolated instances of uncharitable “http://dokterpoker.org/app/img/panduan.html judgments and decrees http://dokterpoker.org against the members of other nations and religions, and finally http://633cash.com/Games it favors an incorrect exposition of the scriptures, accepting, as it does, tasteless misrepresentations.http://633cash.com/Games

The Babylonian http://633cash.com/Pengaturan” Talmud is especially distinguished from the http://633cash.com/Daftar Jerusalem or Palestine Talmud by http://633cash.com/Promo the flights of thought, the penetration of http://633cash.com/Deposit mind, the flashes of genius, which rise and vanish again. It was for http://633cash.com/Withdraw this reason that the Babylonian rather http://633cash.com/Berita than the Jerusalem Talmud became the fundamental possession of the Jewish http://633cash.com/Girl Race, its life breath, http://633cash.com/Livescore its very soul, nature and mankind, http://yakuza4d.com/ powers and events, were for the Jewish http://yakuza4d.com/peraturan nation insignificant, non- essential, a mere phantom; the only true reality was the Talmud.” (Professor H. Graetz, History of the Jews).

And finally it came Spain’s turn. http://yakuza4d.com/home Persecution had occurred there on “http://yakuza4d.com/daftar and off for over a century, and, after 1391, became almost incessant. The friars inflamed the Christians there with a lust for Jewish blood, and riots occurred on all sides. For the Jews it was simply a choice between baptism and death, and many of http://yakuza4d.com/cara_main them submitted http://yakuza4d.com/hasil to baptism.

But almost always conversion on thee terms http://yakuza4d.com/buku_mimpi was only outward and http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/peraturan.html false. Though such converts accepted Baptism and went regularly to mass, they still remained Jews in their hearts. They http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/jadwal.html were called Marrano, ‘http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/promo.html Accursed Ones,’ and there http://raksasapoker.com/app/img/panduan.html were perhaps a hundred thousand of them. Often they possessed enormous wealth. Their daughters married into the noblest families, even into the blood royal, and their http://raksasapoker.com/ sons sometimes entered the Church and rose to the highest offices. It is said that even one of the popes was of this Marrano stock.