Since the election of Donald Trump, there has been a steady media holler attributing his success among white, working-class voters to their justifiable frustrations over economic restructuring, particularly deindustrialization and the flight of manufacturing jobs overseas. Certainly the current neoliberal economy (with its unprecedented inequality) negatively impacts poor, working-, and middle-class people of all races, and I do not mean to minimize anyone’s suffering, but it takes a near magical historical amnesia to view white America as the group most negatively impacted by deindustrialization.

The rusting of the Rust Belt began in the decades after World War II, as manufacturing left industrial cities in the Northeast and Midwest for the suburbs, the Sunbelt and eventually overseas. This manufacturing flight occurred at the exact same historical moment that millions of African Americans were leaving the Jim Crow South and hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans were leaving the colonial poverty of the island to move to these same industrial cities. They arrived at the very centers of U.S. manufacturing, only to watch urban industries close up shop and the jobs disappear.

While manufacturers were abandoning Rust Belt cities, so were many of the white residents, drawn by government-subsidized development out into the mushrooming and overwhelmingly segregated suburbs. After those with means moved to the suburbs to live and work, the retail economy of cities was hit hard, too, as shoppers abandoned urban downtowns in favor of suburban malls. White residential flight combined with manufacturing and retail flight to devastate city economies in the Northeast and Midwest, precipitating a fiscal crisis by the 1970s that eviscerated urban education and public safety services. Rust Belt cities went up in flames, as arson tore through disinvested neighborhoods. Into the vacuum left by the virtual disappearance of a formal economy flowed the drug trade, fueled by a ceaseless demand in the vast suburban marketplace.

This was the beginning of the economic restructuring that has working and unemployed people across the political spectrum so up in arms. This was the first wave of deindustrialization that culminated in the flight of manufacturing overseas, entire swathes of the country now home to abandoned factories and hungry families.

And its victims were overwhelmingly the Black and Puerto Rican residents who arrived in industrial cities after WWII: last hired and first fired due to discriminatory employment practices and trapped in corroding urban centers by discriminatory realtor and mortgage practices. Although rural poverty persisted, much of white America largely escaped crumbling industrial cities and flourished during this first wave of deindustrialization in the new suburban economy with its array of educational opportunities.

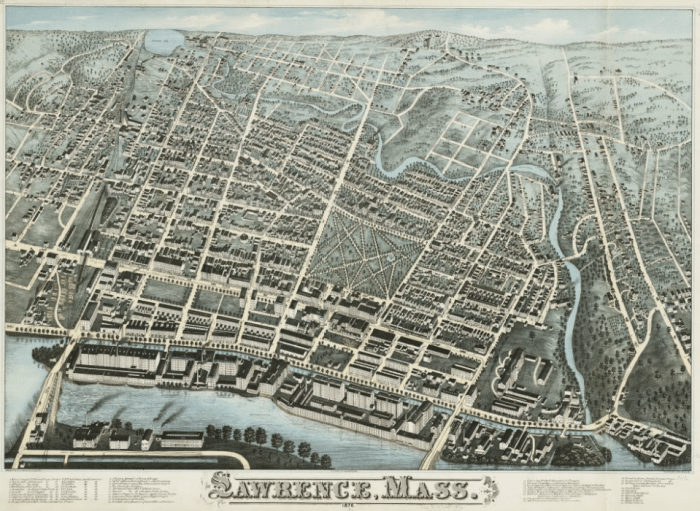

The Massachusetts mill city of Lawrence illustrates the impact of manufacturing flight on urban communities of color brilliantly. Lawrence was the “woolen worsted capital of the world” in the early 20th century, a manufacturing giant, the river that bisected it lined with mammoth brick mills, filled with immigrant labor powering the nation’s status as the global industrial leader.

In the decades after World War II, these manufacturers abandoned the city, as did most of its white residents, and many of its stores, theaters and offices. Puerto Rican and other Latina/o workers were recruited into Lawrence by the few remaining, struggling, industries in the 1960s, but these too shut down by the 1980s, leading to widespread poverty and joblessness. By the early 1990s, Latina/os were a near majority of the struggling city’s population, and they had a 25 percent unemployment rate. Lawrence was in an extreme state of fiscal crisis, its schools and public safety sector dramatically underfunded, its residents living in fear of crime and the fires that regularly tore through the impoverished city.

This was the reality of economic restructuring.

Deindustrialization provoked widespread urban crisis throughout Rust Belt cities from the 1960s through at least the early 1990s (in some cities, this crisis persists). The communities of color who suffered from these economic dislocations received very little sympathy. Instead, they were widely stigmatized as lazy and/or dangerous. The social safety net of welfare was essentially dismantled and the system of mass incarceration was constructed. Now that attention has turned to the impact of economic restructuring on white people, the blame-the-victim approach is finally waning, but this mentality and the policies it enabled have long been both misguided and counterproductive.

The new sympathy for victims of economic restructuring resembles the current compassionate approach to opioid addiction dominating political discourse. Finally, there is recognition that addiction is a disease and treating it requires investing in broad public health strategies. Where was that compassionate insight into the nature of addiction during the crack epidemic of the 1980s? Instead of public health programs, people of color in urban communities encountered aggressive and discriminatory policing, arrests, sentencing and incarceration, and widespread condemnation and stigmatization from the media and most politicians. Of course, we can’t go back and change the past, right? But actually many of the people targeted by the racist policies of the “War on Drugs” are still incarcerated. Now that white addiction has awoken our collective compassion, can we not extend that new awareness to those still suffering from our pre-awakening ignorance?

The wildly sympathetic (some might even say predatory) populist line on white unemployment views it as an economic and political problem to be solved by engaged politicians. And it is. But it is tragic that the political will to temper the dislocations caused by economic restructuring has only arisen now, when the nation realizes that deindustrialization is impacting white people. Politicians had no real interest in saving jobs in American inner cities when they were in flames (unlike now, when “inner city” is just as likely to refer to Times Square as to South Side Chicago). Yes, widespread joblessness is an economic and political problem, not simply an individual or cultural one. That is true now, and that was equally true during the era of urban crisis. Recognizing the flawed political responses of this earlier era is key to addressing its continuing unjust legacies.

But of course, the compassionate discourse on joblessness does not itself create jobs, and there are no concrete policy changes on the horizon that will stem this swelling tide of economic inequality, frustration, and despair. This, too, is the legacy of the crisis era: the reason we are so politically unprepared to reckon with the impact of economic restructuring is because few in the U.S. did more than tsk, tsk at the “inner city” for the first half century of manufacturing flight. Racistly dismissing the problems caused by economic restructuring as a “culture of pathology” distracted the nation from looking for solutions and allowed time for the wound to fester and the infection to spread. Now we are deeply and pervasively sick with income inequality, economic despair and a democracy corrupted by wealth.

The lesson is that white America cannot insulate itself, through racism, from the perils of global capitalism. The time is long overdue for an antiracist solution to neoliberal economic restructuring.

***

Llana Barber is the author of Latino City: Immigration and Urban Crisis in Lawrence, Massachusetts, 1945-2000.