June 2, 2020, San Juan, Puerto Rico during a Black Lives Matter protest (Photo by Claudia Carbonell Pericot via Colectiva Feminista en Construcción)

“There’s a move afoot to divide us. It’s being done by Afro-Saxons and coconuts. People who would have us believe that there is a separate gulf between two nations: Black and Latino. (Crowd claps). This is not the poem y’all (the crowd laughs). I’m telling you there’s no difference between Buford, North Carolina and Ponce, Puerto Rico, you hear me? (Crowd claps and someone yells, ‘Right!’). Too many of us grew up in the projects and did bids in the joint together to have anyone divide us on the basis of language. Mambo is Black, Merengue is Black, R&B is Black, Joropo is Black, Flamenco is Black, Guaguancó is Black, Bomba is Black. Be careful…(Sudden silence). They will come to you and say, ‘Be careful of those hordes of Spanish people.’ Fuck them (Crowd claps).” — Felipe Luiciano

This spoken word poem, written and performed by the Afro Puerto Rican writer and activist Felipe Luciano, captures ideas around the role of Blackness within Latinx communities. During the 1970s and 1980s, Black Puerto Rican activism was still operating along the lines of heritage and cultural nationalism. Following in the steps of Afro-Puerto Ricans of the past such as Fortunato Vizarrondo, Ruth Fernandez among others, Luciano’s political stance around Blackness was both diasporic and revolutionary for its time.

According to Dr. Urayoán Noel: “In essence, Luciano’s ‘browning’ of the jíbaro makes sense of Puerto Rico’s history while inserting the New York Puerto Rican into a larger Afro-diasporic imaginary, thus providing new models for affective and political relation.”

Luciano’s Black figure —whose ideas of symbolic nationalism, culture, and ancestry asserted an Afro-diasporic unity— was interpreted as shared experience of racialization and oppression in the United States (as stated by Noel) with all Puerto Ricans and by extension other Latinxs. Meaning, Luciano’s stance mirrors (albeit differently) Vizcarrondo’s famous poem “¿Y tu agüela, aonde ejtá? (And your grandmother, where is she at?), which sought to highlight and expose the island’s racism by claiming the African ancestry inherent in all Puerto Ricans, including those who were of European descent. By further browning Puerto Ricanness and by extension Latinidad, racism could be combated. This is an idea that persists today and being challenged by many Afro-Latinx educators, writers and activists.

However, many educators and writers have currently begun to use “¿Y tu agüela aonde ejtá?” as a conceptual framework for digging up the past in order to create historical literacy. In this sense, “¿Y tu agüela aonde ejtá?” can lead to productive conversations around race, African slavery, and homophobia in order to understand their historical legacy up to the present.

The Nuyorican poet and writers Lemon Anderson and Jesus Gonzalez wrote and partook in an episode dedicated to Puerto Rico in the second season of “She’s Gotta Have It.” Recently, Bre from Hot 97 interviewed Anderson and Gonzales on the racial issues in Puerto Rico. Anderson ––who is a White Puerto Rican wearing the Puerto Rican Flag with Pan African colors–– responded by emphasizing the slave trade and how slaves were dropped off in different ports throughout the Caribbean. Anthony Ramos, Fat Joe, and Spike Lee continue this legacy of using Blackness as a way to brown Puerto Ricans while dismissing White racial privilege in Latinx communities and in countries like Puerto Rico. In the episode, Puerto Ricans were overly “Blackened” in the island, thus attempting to over emphasize the island’s Blackness at the expense of the countries’ overwhelming White majority population.

As already mentioned, these symbolic gestures of over emphasizing Puerto Rican Blackness as the antidote to anti-Black racism and as a way to racialize all Latinos as non-White has been questioned by many scholars and writers and activists including myself. Cesar Várgas was one of the first to use the term White Latinos (or White Hispanics), which allowed myself and others to push back the use of Blackness as a way to underscore non-White racial identity. Due to scholars and their tendency to not cite non peer-reviewed articles, important figures like Vargas get overshadowed in bibliographies in academic articles on White Latinidad in the United States.

Despite people like Fat Joe —who continues to claim that all Latinos are Black (which, by its very logic, universalizes or falsely Latinizes Afro Latinxs’ experiences with systemic racism)— my aim is to create a conceptual framework that will allow future generations of Afro Puerto Ricans, Afro Latinxs, including allies, to push back against this continuous cycle of using Blackness as an extension of Puerto Ricans and/or Latinidad and begin having conversations around race, racism, Blackness, and White Latinidad as realities built on systemic and institutional prisms of power.

As most of us know at this point, no one is born with a race.

Furthermore, according to Roy Wilson, “The word race has many connotations and is difficult to define precisely. On the surface, the concept appears simple enough: a biological construct intended as a means of classifying different groups of people possessing common physical characteristics and sociocultural affinities. However, objective and scientific criteria for establishing biological differences between races have proved elusive. For sure, genetic differences can and do exist between populations. Yet, the mapping of the human genome has demonstrated that racial categories do not exist at the genetic level. Further, it is universally accepted that there is overwhelmingly more genetic variability within a population group than between the groups.”

Race is a symbolic and systemic category according to specific social and historical contexts based on phenotype or ancestry that is misrecognized as a natural category According to Isar Godreau, “Scripts of Blackness are constructed in relationship with competing notions of whiteness, some of which draw heavily from Eurocentric discourses on Hispanophilia.”

As stated by Torres-Saillant, “A dogma begotten by the colonial transaction nearly five centuries ago, racism emerged to address the moral transgressions that Christian nations incurred when they climbed leadership roles in imperial domination.” It is clear that race has more to do with politics, historical and contemporary systemic forms of domination, belief systems, rather than genetics, biology, ancestry, nationalism and culture. Although Latinos scholars and activists has repeatedly argued their distinct racial experience from the United States, Torres-Saillant argues that White supremacist values are not erased and proposes for a recognition of race as well as ethnicity as way to strengthen Latino communities throughout the United States.

In this essay, my aim is to highlight six fallacies on race. These fallacies are inspired by the article titled “What Is Racial Domination” (2009), written by Matthew Desmond and Mustafa Emirbayer. Many naysayers argue that race and racism operate “differently” in Puerto Rico than in the United States. I argue that, if race and racial domination are a systemic issue that began with European colonialism and transformed throughout centuries across the Americas, then it should not be surprising to find similarities and differences within social relations of domination, regardless of region. Although there may be more fallacies (I am sure there are), they can hopefully help serve as an analytical guide that will help people center an more appropriate conversation on race whenever someone (usually a White Latinx) attempts to reduce race to phenotype, ancestry, ethnicity, or metonymic nationalism.

Social and Historical Context

As many scholars have argued, racial taxonomies are bound to their specific social and historical contexts. The Spanish crown used biological and zoological metaphors in order to describe classifications. The idea of blood and purity became metaphors for maintaining status which would be coterminous with maintaining European phenotypes and power. For example, when the concept of limpieza de sangre traveled to Spanish America, it was expanded to include a further condition: a notary could not be a person of African or indigenous descent. Although this prohibition may have been respected initially, complaints that mestizo, mulatto, and illegitimate people were working as notaries began to reach the Consejo de Indias and the king. In response, royal decrees and orders were issued to control access to the occupation and office of notary for people of mixed descent and illegitimate birth.

To be of color was determined as a social condition. But racial domination became a way in which people of European descent created the idea of what is known around the world as White Supremacy or supremacia blanca. As already stated, many Puerto Ricans will argue that all Puerto Ricans were affected by the Spanish Crown. It nonetheless seems unlikely that insular White Puerto Ricans did not participate in White racial domination In the Puerto Rican context, although this needs to be further studied as well. The Taíno was invented within the context of European colonization, as native people to be killed, enslaved, or tortured. For centuries, Africans were associated with bondage, savagery and immoral. By the middle of the 20th century, race was understood as a mixture of three races, a context created under its colonial relationship with the United States.

What Is Racial Domination?

Racial domination is a term that tends to work well with my students because it frames race as social relations based on systemic and institutional issues. According to Desmond and Emirbayer, institutional racism is the systemic, White domination of people of color, embedded and operating in corporations, universities, legal systems, political bodies, cultural life, and other social collectives. In the Puerto Rican context, racial domination has existed for centuries. For example, the Black Codes by Puerto Rico’s General Captain Juan Prim in 1848.

This code followed earlier attempts to control African populations in Puerto Rico, such as with Governor Salvador Meléndez y Bruna, who constituted laws that banned any mention of abolishing slavery in Puerto Rico. Years later, the capture of escaped enslaved Africans was legalized. However, many Puerto Ricans will say this has nothing to do with Puerto Ricans but everything to do with the Spanish crown. For them, Puerto Rico being a Spanish colony at the time absolves them for any wrongdoing. It is still not clear how populations in Puerto Rico reacted to these laws and more analysis needs to be studied. However, what we do know is that these laws affected Black people in particular and not all Puerto Ricans. Although Puerto Ricans will say Spanish policies affect all Puerto Ricans, it is important to underscore the particular racial terror that affected people of African descent.

Recently, the Colectiva Feminista en Construcción, among others, marched in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico to express solidarity with the recent killing of George Floyd but also revisited previous cases of anti-Blackness in Puerto Rico, such as the criminalizing of Alma Yadira Cruz and recent police killings of black (including Black LGBTQ) Puerto Ricans.

#BlackLivesMattter #LasVidasNegrasImportan @ColeFeminista desde #PuertoRico pic.twitter.com/45VmjJsg5e

— Defend Puerto Rico (@DefendPR) June 2, 2020

I seriously was convinced I would never see this in my lifetime. What is different from this march in comparison to past conversations around this issue is that these protestors are not using Blackness as an extension of Puerto Ricanness. The Colectiva Feminista, among other activists, are very strictly focusing on Black and LGBTQ lives. Although they use some symbolic nationalism in order to promote their case, it remains to be seen how future marches and activist strategies against anti-Blackness will look like.

According to Marisol Lebrón, “Rather than providing safety, punitive policing has in many ways deepened existing societal inequalities and further limited life chances in Puerto Rico’s racially and economically marginalized communities. Further, it has often done so in a way that has reproduced and reinvigorated social hierarchies of value and belonging in the name of public safety.”

Meaning, Puerto Rico’s police has a history of marginalizing Black people without any consequences within the law especially when it comes to racial profiling.

Six Fallacies of Race

1. Phenotypic and Ancestral Fallacy: Race in Puerto Rico has always been associated with phenotype and ancestry. The false discourse of “we’re all mixed” has led to systemic racism being dismissed or reduced to phenotype. In a Puerto Rican context, allegedly, one’s phenotype is not as important as one’s ancestry. As such, the African, the Spanish (or European) and “Taínos” are considered separate races that merged into one distinct race (sounds like a sci-fi story) which is Puerto Rican.

In this sense, although people may look Black, White or Mulatto, that is not their race. For them, their race is their ancestry and their ancestry is their Puerto Ricanness. This is why many Puerto Ricans of European descent will say, “I’m not White.” Meaning, they are not White although they admit that racism does exist. This paradox of admitting some form of racism in Puerto Rico but not wanting to be called White, which is associated with European colonizers and with White Anglo imaginary in the U.S., is the reason for its rejection. Getting called White becomes then the same thing as being called non-Puerto Rican, a racist and/or a White American.

This process of rejection is what Bonilla Silva calls racism without racists. Meaning, racism operates in a systematic way that codifies anti-Blackness within covert forms of oppression. By saying there can be Black people and no White people, it creates a Boogie Man effect that centers solely on institutions without making society responsible. Many White Puerto Rican scholars have made their entire careers by talking about Black people without having to account for White racial identity. Their defense is usually, “Race operates differently in Puerto Rico.” A good follow up to that question can be, “Do you mean systemic and institutional racism operates differently?” We cannot conflate the reality of racial phenotype with institutional racism. Unfortunately, the “y tu agüela dónde está” has reinforced systemic racism by invisibilizing and minimizing its systemic and continuum for hundreds of years.

A couple of years ago, I was sitting in a restaurant across from Hunter College with some White Puerto Rican professors. We had just finished attending some talk on Puerto Rican issues taking place on the island. As soon as we sit down, one of them starts talking about his Black sister and other family members who were Black. He proceeds to talk about his struggle with poverty. He ends the conversation by saying, “I’m not White.” I just stood there confused not knowing what to say. I had just finished my MA in history from the University of Puerto Rico and was starting a second Masters at Columbia University.

Why would this guy use his Black sister to justify his non-Whiteness?

I thought that was strange in general, especially coming from a professor who specializes in Puerto Rican studies. Whatever race was, that couldn’t be it. I admit, I was not trained at the time to deal with these awkward instances of Puerto Ricans reducing race to phenotype or roots. In the last couple of years, my training at Columbia and my PhD program have given me some information on how to deal with these issues regarding race amongst Puerto Ricans and other folks from Latin America.

The guy who used his family members in order to justify his non-Whiteness clearly analyzes race differently when he compares race in the U.S. and Puerto Rico. One of the ways White Puerto Ricans avoid implicating themselves in White racial domination is by denying their White racial identity altogether. Many are incapable of naming White racial identity outside of the U.S. altogether. The question to ask ourselves is: Exactly how and why do non-Black people like Fat Joe claim a Black racial identity and what allows such claims to stand legibly? What are the cognitive dynamics around making such a problematic claim?

The fact that in 2020, Latino Studies continues to limit racial politics to racism and Black people proves how little effort there is to engage with this colonial legacy. The emphasis on Black racial identity as isolated from White racial identity —which would cause an outcry in the U.S.— has remained the norm and will remain the norm until Afro Latinxs themselves begin to take a new approach to white Latino racial identity. We cannot expect white Latino scholars to do it. Doing so would compromise their expertise in Black people’s experiences and lead to Black people being active participants in their asymmetrical and systemic sociality to White Latinos and White Latinidad.

Similar to White Americans, White Latinos are committed to social justice as long as they’re getting paid and recognized in the process. Similar to White Americans, White Latinxs are not liberal and radical for free and without some other form of exchange. How many non-Black Latinx scholars have made their entire academic career by writing about Black and Indigenous Latinos and about Black and Indigenous people in Latin America? Out of those scholars, how many of them have written and published about White Latinidad either in Latin America, the Caribbean, or the U.S. with an attempt to both decenter White racial politics in the U.S. while centering their own experiences? How many White Latinx editors do you see in major Latinx journals, some even in Afro Latinx journals? Further, many of these scholars have made academic careers by being Orisha practitioners.

When these issues surface, the perfect retort is, “Well…I’m not White in the United States. Race operates differently in the United States.” While many scholars keep publishing articles about Black and Indigenous/Native identities, they continue to neglect white Latin American identities as well as White Latinos living in the U.S. Saying “I’m not racist,” often said by White Americans, is related to the same systemic structures that propel White Latinxs to say, “I’m not White.”

Not too long ago, during a zoom conversation, Dr. Hilda Lloréns, an Afro Puerto Rican scholar, mentioned the term strategic ambiguity, defined as the art of making a claim using language that avoids specifics and claims it has been an important cornerstone in academic writing. Terms such as, “allegedly White,” “how Puerto Ricans became White,” “White-passing,” and “light skin” (I’m not citing the scholars who do this; I’ve burned enough bridges in the past) are forms of strategic ambiguity that seek to minimize the multi-dimensions of structural White racial identity as they function transnationally. Lloréns calls the process of racial passing for those who are whiter on the phenotypic spectrum who enjoy privilege. Comfortable with the U.S. dominance of critical Whiteness Studies, Latinx and Latin American scholars are able to use terms like Black with very specific political connotation while neglecting or rejecting the usage of White racial identity in political, philological, and phenomenological terms.

“In your face,” explicit racist attacks from White Latinos in the U.S. are understood as a deviance from Brown people of color that gets accepted as White supremacy, while ignoring the imbricated ideological context of White Latinx racial domination. For example, Alex Michael Ramos, the White Puerto Rican who was found guilty of malicious wounding in the Charlottesville parking garage beating of Black American DeAndre Harris. Ramos makes two interconnected claims: 1) He’s not racist because he’s Puerto Rican and 2) He’s not White because he’s Puerto Rican. What does it mean to exclude yourself from racist vitriol or from systemic White privilege by claiming you are not White?

How is Fat Joe accounting for this? Is he confused about his “racially mixed heritage” as many writers have argued or is he continuing a legacy of White racial domination and anti-Blackness that has been operating in Puerto Rico for hundreds of years? The Afro Puerto Rican queer scholar, writer, and activist Yolanda Pizarro posed an important question in her 2018 book “Blancoides.” Here it is: “Si se puede decir negroide, se puede decir blancoide?” If there is a Negroid, can there be a Whitegroid? Pizarro’s question may seem non-controversial at first glance, but if we are to take into account the hundreds of years of European immigration to Puerto Rico —the very specific anti-Blackness by White descents on the island— this question in and of itself challenges the entire Puerto Rican Studies canon. It begs the question, for how many centuries have White Puerto Ricans like Alex Michael Ramos gotten away with anti-Black hate crimes in the name of Puerto Rican independence or neo-nationalism? Why is recognizing Blackness and not Whiteness a perceived reality at all?

Pizarro’s question travels and unravels an issue beyond Puerto Rico, disrupting fallacious preconceived notions of race in the Puerto Rican diaspora. For how many more years are we going to allow White Puerto Ricans and, by extension, white Latinos to get away with enjoying White racial domination by simply stating they are confused about their racial heritage? Is that really how race works? And based on heritage and made-up Black grandmothers? The “All Puerto Ricans Are Black” argument has led to the insidious replication of White racial domination. Still, most White Puerto Rican scholars remain silent on this particular issue albeit the few who associate White Latinidad with simply having socio-economic power. This is a postracial an utterly limiting, violent analysis.

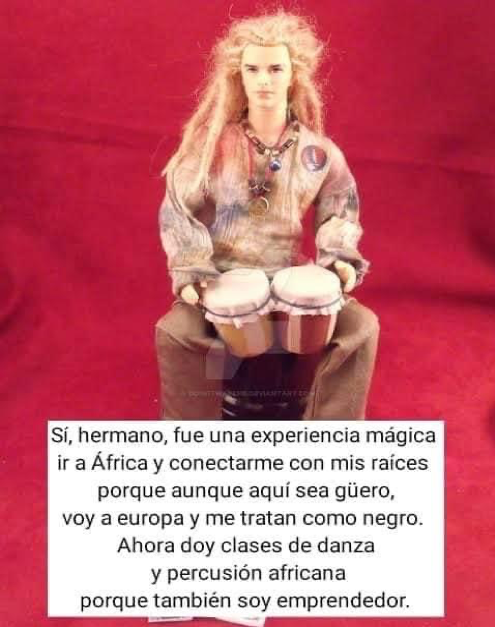

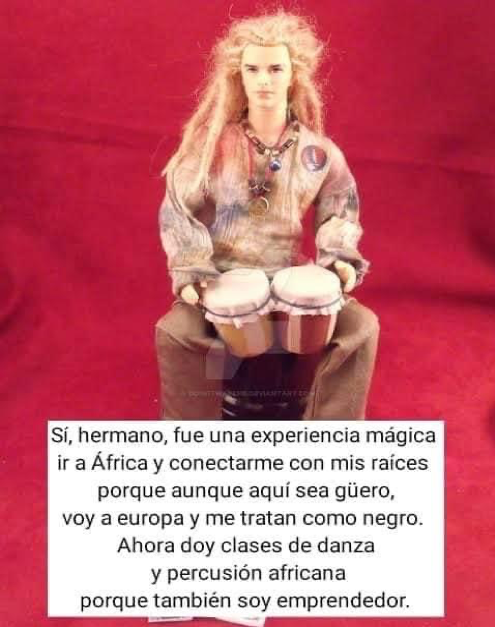

Other mediums, such as the now-defunct Facebook page “La Sociedad de BlanquiPuertorros,” utilize satire in order to highlight white Puerto Rican privilege.

Although satirical, these social media posts underscore the degree of hypocrisy of those who get to claim African heritage but continue to enjoy White racial privilege. Many people are noticing this double standard are using multimodal forms of activism to educate the public.

The concept that Puerto Ricans are a racial group with an internal (national) genotype regardless of phenotype, has been naturalized for the past century and a half. Race is misrecognized as natural and thus relies on the unchangeability of Puerto Ricanness, rooted on racial admixture in order to be naturalized. When Puerto Ricans say they cannot be White or Black because other family members are of a certain phenotype, they are misrecognizing race as natural and biological Instead of understanding how social powers, economic forces, political institutions, and cultural practices have brought about these divisions. Naturalized categories around race are powerful. They are the belief systems which ensure Puerto Ricans wave the Puerto Rican flag as the representation of all Puerto Ricans. These racially charged naturalizing processes have made envisioning Puerto Rican identity in different ways almost impossible, unfathomable.

2. Individualistic Fallacy: Here, racism is assumed to belong to the realm of ideas and prejudices. Racism is only the collection of nasty thoughts that a “racist individual” has about another group. Someone operating with this fallacy thinks of racism as one thinks of a crime and, therefore, divides the world into two types of people: those guilty of the crime of racism and those innocent of the crime. However, according to Torres-Saillant:

“Without admitting to the horror of our beginnings as a civilization (namely the theft, destruction, murder, and mistreatment that it took to build our modern societies in the hemisphere we will go nowhere. We will continue to restrict the field of our social action to responding to individual expressions of the problem rather addressing its root causes. Punishing racist acts may satisfy the dictates of the law and perhaps offer partial consolation to victims and their loved ones, but it does not address the problem that triggers the acts in the first place.”

Crucial to this misconceived notion of racism is intentionality. According to Desmond and Emirbayer: “Did I intentionally act racist? Did I cross the street because I was scared of the Hispanic man walking toward me, or did I cross for no apparent reason?”

Upon answering “no” to the question of intentionality, one assumes that one can classify one’s own actions as “nonracist,” despite the character of those actions, and go about his or her business as innocent. This conception of racism simply will not do, for it fails to account for the racism that is woven into the very fabric of our schools, political institutions, labor markets, and neighborhoods. Conflating racism with prejudice, as Herbert Blumer pointed more than 60 years ago, ignores the more systematic and structural forms of racism; it looks for racism within individuals and not institutions. Labeling someone a “racist” shifts our attention from the social surroundings that enforce racial inequalities and miseries to the individual with biases. It also lets the accuser off hook —“He is a racist; I am not”— and treats racism as aberrant and strange, whereas American racism is rather normal.

In Puerto Rico, racism is assumed to be of a couple of confused individuals who lack the education to understand our supposed “racial mix.” Meaning, racism is interpreted as an aberration of our issues. At the University of Puerto Rico, students will often say that, “My uncle is racist” or “My mom is racist” in order to 1) undermine racism as a systemic issue and, 2) leave themselves off the hook from being called a racist. I myself have fallen for this issue many times. Consider the news of a woman who drew racist drawings in Canóvanas, Puerto Rico as an attempt to symbolically profile the neighbors husband and kids as racist.

When I shared this on Twitter, there were over 700 reshares in less than four hours. People were saying things like, “Where do they live so we can visit them,” “I’m going to burn their house down,” “What a racist,” etc.

Racism in canovanas, Puerto Rico. White Puerto Rican’s haven’t experienced Black rage in a loooong time. They get a small snippet this week and go full white supremacist and violent real quick. @CentroPR @latinorebels @PuertoRicoSerio @VoceroPR pic.twitter.com/3LuBsoTGfU

— William Garcia-Medina (@afrolatinoed) June 10, 2020

Although calling out this symbolic violence is important, it is also important to underscore racism as an institutional issue and fight for reforms such as affirmative action, policies, and institutional spaces that systemically combat racism. Another case was the case of the Black girl with special needs who was bullied in school and arrested because of the school administration. Many will accuse the principal of being a racist but scholars like Isar Godreau and others have already underscored the systemic racist rampant within Puerto Rico’s education system. We have to remind ourselves, these supposed individual acts of racism are what has been recorded because of recent technological innovations, but we should ask: For how many centuries have Puerto Ricans actually behaved this way?

I will remind you that tonight Kobbo Santarrosa said that he nor his puppet character La Comay are racist. Mocking of @RiveraLassen as a black servant last Friday was just 1 example. Another one? From back in the day when he LITERALLY compared Black Puerto Ricans to a chimpanzee. https://t.co/f3H4huowAy

— Julio Ricardo Varela (@julito77) June 16, 2020

3. Legalistic Fallacy: This fallacy conflates de jure legal progress with de facto racial progress. One who operates under the legalistic fallacy assumes that abolishing racist laws (racism in principle!) automatically leads to the abolition of racism writ large (racism in practice!). After all, we would not make the same mistake when it comes to other criminalized acts: Laws against theft do not mean that one’s car will never be stolen. The Canóvanas case exemplify this issue. Although they went to the authorities in order to deal with their racist neighbor, on multiple occasions, the authorities and the municipality did nothing on the matter. Only after multiple attempts and dissemination of the story, the municipality then decided to get involved. Article Two of the Constitution of Puerto Rico —titled as the Bill of Rights (Spanish: Carta de Derecho)— lists the most important rights held by the citizens of Puerto Rico. It also establishes two fundamental declarations, that “the dignity of the human being is inviolable” and that all men are equal before the law. Of course this de jure statement means nothing in practice.

4. Tokenistic Fallacy: According to Desmond and Emirbayer, tokenistic fallacy assumes that the presence of people of color in influential positions is evidence of the eradication of racial obstacles. In the Puerto Rican case, the fact that Black luminaries such as José Celso Barbosa, Pedro Albizu Campos, Rafael and Celestina Cordero, Rogelio Figueroa (Coquí Political Party), alongside others who have had some access to the political spotlight in the past, should not assume that Puerto Rico is all for racial harmony. In the Puerto Rican case, having a couple of Black journalists and anchors such as Pedro Rosa Nales and Julio Rivera Saniel does not mean all Black people in Puerto Rico have the same opportunities. People who want to maintain anti-Black racism will tend to look for successful Black tokens in order to justify their stance, in our case using successful Black people in order to underscore myths of racial democracy.

5. Ahistorical Fallacy: This fallacy renders history impotent. However, in the Puerto Rican case, because we are all supposed to be mixed and allegedly there is no such thing as a White Puerto Rican ––even though census records and centuries of de jure and de facto anti-Black subjugation would state otherwise–– legacies of slavery, race-based exploitation, and racist propaganda distribution across the culture and entertainment industry supposedly affects us all equally. The erroneous idea that Black insurrectionists like Marcos Xiorro (among others) was a time before or during we were all “getting mixed” is erroneous and invisibilizes the Black experience in Puerto Rico. The idea that the abolition of slavery in Puerto Rico is a commemoration for all Puerto Ricans and should equate our colonial relationship with the U.S. makes us “all slaves” as we were under the Spanish, when our African ancestors were enslaved.

This transference of Black subjugation towards a form of Puerto Rican subjugation continues to operate. In this instance, Black people are being asked to be patriotic at the expense of their human rights. Another fallacious argument might posit that Black people who experienced Black subjugation in the past are not connected to the struggles of Black people today because those Black people from the past are not the same mixed Black people that exist today. Similarly, European immigration to Puerto Rico can be interpreted as something of the past, when there was White people, before we all became mixed with a similar genetic recipe that is supposed to account for race as the fixed manifestation of Puerto Ricanness.

6. Fixed Fallacy: According to Desmond and Emirbayer, “Those who assume that racism is fixed —that it is immutable, constant across time and space— partake in the fixed fallacy. Since they take racism to be something that does not develop at all, those who understand racism through the fixed fallacy are often led to ask questions such as: ‘Has racism increased or decreased in the past decade?’ And because practitioners of the fixed fallacy usually take as their standard definition of racism only the most heinous forms —racial violence, for example— they confidently conclude that, indeed, things have gotten better.”

The history of Puerto Rico is decided between the era of different racial coexisting eras on the island with that of the time when we all mixed into what is considered Puerto Rican. This “mixed” Puerto Rican became fully manifested during the U.S. invasion of Puerto Rico during the late 19th century, up to the present day. Before this time, we were not yet all “mixed” and can be considered proto-Puerto Ricans such as enslaved Africans or European immigrants. After a certain time, Puerto Ricans became a fixed racial group incapable of changing because it is embedded in the essence of the people (I’m not sure how exactly). Similar to the U.S., many Puerto Ricans will argue that “racism is not as bad as it once was during the time of slavery in Puerto Rico” and that “it has never been as bad as it was in the United States.” As a white Puerto Rican student told me once at the University of Puerto Rico when I was a student there, “At least we didn’t hang Black people.”

For those involved with the fixed fallacy, racism has to be similar to the U.S. in order to highlight it as an institutional issue. Arguing that there can be Black Puerto Ricans but no such thing as a White Puerto Rican creates a loophole that on the one hand, acknowledges Black people in Puerto Rico but still considers them physical traces of all of our ancestors. Why? Because by acknowledging Blackness and not Whiteness, White racial identity is kept in the realm of “the past” while also minimizing the actual acknowledgement of Black subjugation for centuries by White supremacy and white racial domination. Exposing this reality would compromise the very notion of Puerto Ricanness. I myself have witnessed many Nuyorican spoken word artists perform on the Taínos who mixed with the Africans in fixed ways. These fixed fallacies are passed from one generation to the next.

In closing, this piece is intended to recenter the conversation around race and racial domination as systemic issues beyond these being simply a colonial mirroring of the Spanish empire or an aberration of the triracial myth. This generation of Puerto Ricans is becoming a bit wiser and is tackling issues our previous generation were not tackling, such as Latinidad and Blackness not being the same thing. It is an exciting time to witness the activism around anti-Blackness and further inspires me to believe in change not imagined when I was kid. Puerto Rico’s emphasis on racial hierarchies cannot be solved by emphasizing “racial” admixture or getting everyone to vote Black on the census while Blackness continues to be reduced to cultural practices such as salsa, santería, hip-hop, bomba, and spoken word, in order to assert mestizaje or perennial Puerto Ricannness. This generation has also started to think about racial issues in more transnational and diasporic ways although this has been explored by our previous generations. We are indebted to their work and activism.

Nonetheless, simply saying Puerto Ricans are not aware of their “mixed heritage” will not lead to actual reforms or radical changes that will give Black people in Puerto Rico and the Diaspora a better quality of life. In order to achieve actual reforms and change, we have to prepare ourselves and re-center conversations around White Supremacy, White racial domination, and systemic racism in the island and its diaspora beyond resorting to phenotypic categories of race. Furthermore, simply mentioning the extent of racism and culture without addressing centuries-long systemic inequality does not lead to any actual social change unless we continue underscoring systemic injustice against Black people in particular. When someone says, “We’re mixed,” we can teach the younger generation to answer those rebuttals by saying, “What do you mean by mixed?, “Please define race,” “That is not race, race is about systemic domination, not about biology or ethnicity,” and so forth.

What follows are some Pedagogical/Practical tips and questions that I developed alongside AfroLatina scholars Omaris Z. Zamora, Hilda Llorens, and Zaire Dinzey-Flores at our panel at the ALARI conference back in December. I believe these points will aid us in to engage with new conversations around race as both a cultural and systemic issue:

- Admit and Recognize White privilege/Whiteness but also by doing the anti-racist praxis/activism.

- Are you putting your money where your mouth is? Are you partaking in a neo-colonial praxis? (i.e. “academic extractivism”, intellectual/scholarly gentrification).

- White Latinxs are too often called upon to talk about Blackness but Black Latinxs aren’t. This has to stop.

- Recognize that Black Latinx knowledge production is often heard, recycled, and published by non-Black Latinxs and then these very same Black Latinx knowledge producers must cite White Latinx scholars who didn’t cite them in the first place. This creates an academic scholarly environment of epistemic violence and a literal silencing of Black Latinx knowledge producers.

- Academics continue to fail at citing Afro Latinx writers who have not published academically and then take all the credit for our ideas. Please find a way to cite other writers beyond published Afro Latinx academics.

***

William García-Medina: excellent article, analysis and well researched. See this on poet Julia de Burgos: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/julia-de-burgos-1914-1953/

[…] By Thursday morning, Dávila Colón was fired and his show was canceled. The quick response by Univision Communications comes at time where a global movement for Black Lives has raised serious questions about how companies are responding to examples of white supremacy. In addition, the Dávila Colón N-word incident shed a light on how race and racism are topics rarely discussed in Puerto Rico’s public discourse. […]

[…] in the US and those in Latin American countries where Goya products are sold. There are many white Latinx who aspire to US-style whiteness. For Black Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and Cubans, this is […]

[…] un momento histórico en el que el movimiento Black Lives Matter tiene una contraparte española (Las Vidas Negras Importan) y otra portuguesa (Vidas Negras Importam). En todos los casos, los negros del hemisferio americano […]

Soy BORICUA. No tengo problemas de identidad. No me importa si mi piel es oscura.

[…] any consequences within the law, especially when it comes to racial profiling and recent police killings of Black (including LGBTQ+) […]

[…] We live in a historic second through which the Black Lives Matter motion has a Spanish counterpart (Las Vidas Negras Importan) in addition to a Portuguese counterpart (Vidas Negras Importam). In all cases, Black people in the […]