Pilar Navarrete prepares to appear in a play about her life, Bogota, Colombia, March 30, 2022. (Daniela Diaz/Latino Rebels)

BOGOTÁ, Colombia — After an armed conflict left 220,000 civilians dead and displaced more than eight million victims, a peace agreement signed in 2016 between Colombian government and members of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) is now faltering amid new violence.

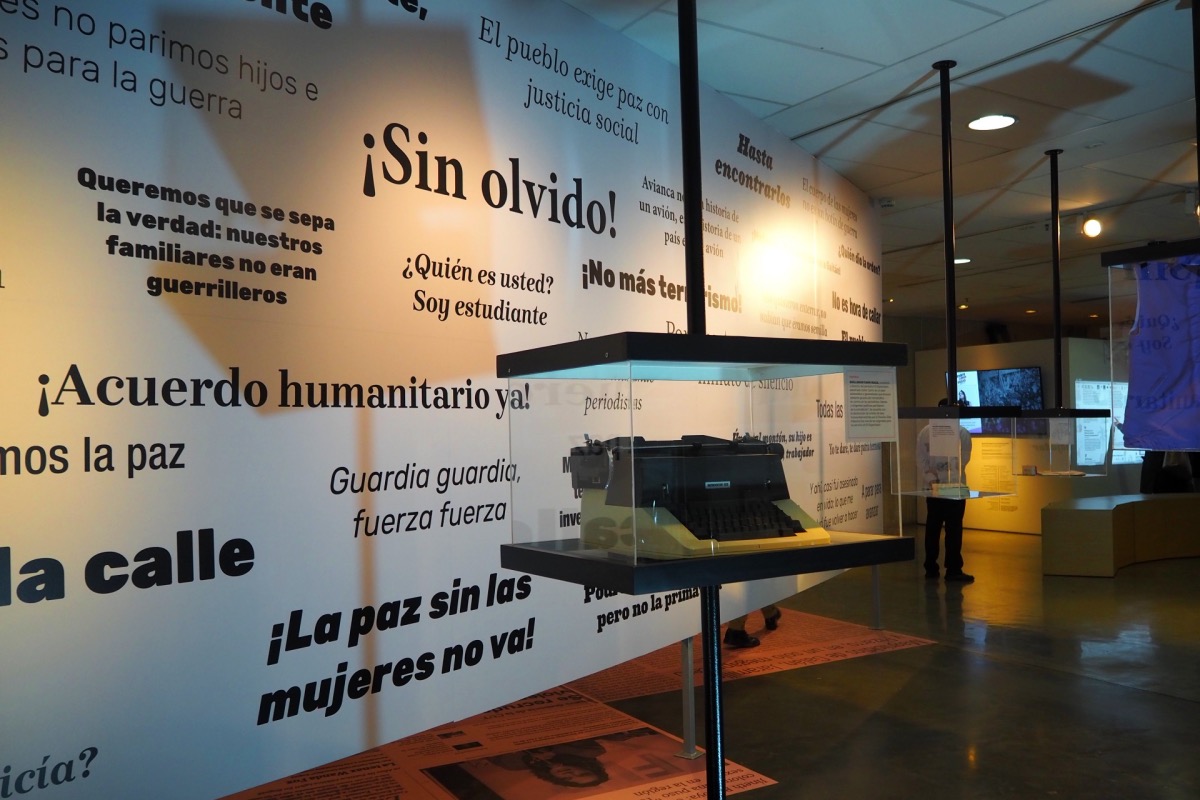

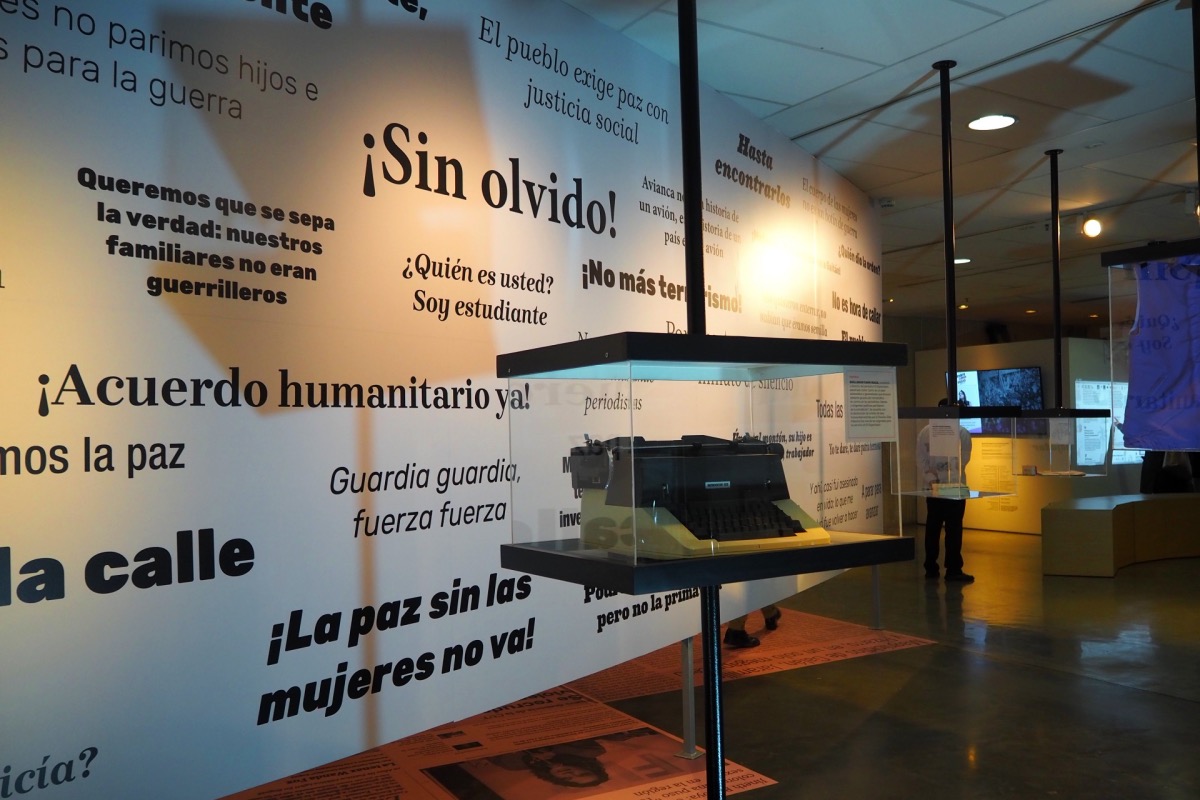

But the people of Colombia are resisting, summed up by an exhibition launched by the Historical Memory District Center whose central message is: “Resisto, luego existo” (I resist, therefore I exist).

Located next to the Central Cemetery in Bogotá, the objects on display include: the typewriter used by Guillermo Cano, director of El Espectador newspaper who was assassinated by Pablo Escobar; the van used by a father to keep alive the memory of his son assassinated by the army in the “false positives” scandal; the notebooks of a member of the Patriotic Union, a left-wing political party that suffered the killing of more than 3,000 of its members by paramilitary forces.

But the message is not pessimistic.

Rodrigo Londoño, former top commander of the FARC guerrillas who signed the peace agreement with the Colombian state in Havana in 2016, was on-hand to assist with the exhibition. He seemed overwhelmed and tired, his war years behind him.

He sat in front of the gallery of photos of social leaders, trade unionists, and journalists killed during the conflict. Each image is a story. “So many memories, so many people. Now the resistance is to build peace,” he told Latino Rebels.

Guillermo Cano´s typewriter on display at the Historical Memory District Center in Bogotá, Colombia, March 23, 2022. (David González/Latino Rebels)

The Historical Memory District Center, which organized the gallery, is a public institution that works to build plural memories and highlight the stories of victims of the conflict. Its director is José Antequera, and, like most Colombians, his own story is marked by violence. His father and namesake, a left-wing politician, was assassinated by paramilitaries assassinated at the Bogotá International Airport in 1989.

One visitor, José Movilla, saw his father’s photo in the gallery. He was a union leader disappeared by the state on May 13, 1993, when José was only a child.

“It was not only physically losing my father but also seeing that my mother completely changed,” he recalled. “She dedicated herself to undertaking the search process.”

“It has been 29, almost 30 years of struggle that we have not been alone,” he added. “We have joined with other pains, with other people who have also gone through catastrophic situations through the political violence of the country.”

Pilar Navarrete walked along the walls of the exhibition. For 36 years, she has been fighting for the memory and the truth about the fate of her husband, who disappeared in one of the most critical events in the contemporary history of Colombia: the taking of the Palace of Justice by the urban guerrilla group M-19 and the subsequent blood and fire during its recapture by the Colombian army in 1985.

Her husband was one of the employees at the coffee shop. He left the palace alive, but was disappeared by military forces along with 11 other people.

Pilar Navarrete, whose husband was disappeared by the Colombian military in 1985. (Daniela Diaz/Latino Rebels)

Pilar pauses in front of the caption: “While the Palace burned on television, the government invented a soccer game… and the country lost” part of the gallery.

An emblematic instance of that moment was when TV stations decided to air a soccer game while the army retook the palace. Pilar was 20 at the time, with three daughters and a husband, Héctor Beltrán.

“He was from the north coast, from Sahagún, Córdoba. He was a happy person,” she recalled.

The last time she saw him, Héctor had a photo of his three children on Halloween. She asked him not to lose it. He never returned.

Then her life became a constant struggle for justice and memory. Together with other family members, and under intense stigmatization, they began to search for the bodies of the disappeared. Only in 2017 did she learn of his fate, when the Colombian government handed over his remains. He had been tortured and killed shortly after leaving the palace.

By the time she found out what had happened to her husband, Pilar was a very different person. Her house in Ciudad Jardín, a popular neighborhood in the south of Bogotá, has become an improvised museum in memory of her fight. Along with photos of her husband and family, there are symbols of the path she has traveled for decades.

She too is a victim, suffering alone the pain of her loss. Her search for justice turned her into another person, and resistance became her daily life.

“I thank life, and I think that this tattoo that I got the day I received his remains has a lot to do with my life,” she explained, pointing to a tattoo of a phoenix on her right arm. “It is rebirth.”

Rodrigo Londoño, former top commander of the FARC guerrillas, assists in the “I resist, therefore, I am” exhibition at the Historical Memory District Center in Bogotá, Colombia, March 23, 2022. (David González/Latino Rebels)

In 2021, protests broke out against the government of Iván Duque. Government forces repressed them with violence. Dozens of people were arrested, and 63 people were killed, according to a United Nations report—most of them by state forces.

In those days Pilar did not stop going out to the street to march. She met other mothers looking for their children, sympathizing with their pain.

“I find it super nice to be able to get up, go for a walk, march, demand, write, tell people, teach them,” she said. “I think that the most difficult thing is when you are left alone. When no one helps anyone, when no one is there to give you a hand.”

Pilar passed her contacts along to the mothers looking for their lost children, telling them where to go and who to talk to. She explained the importance of writing everything down: appointments with the officers, names, dates.

“That’s how most of the women in this country are. One realizes the majority of women are the ones who are in all the organizations resisting and transforming all this,” she said.

Pilar is preparing to appear in a play where she is the protagonist. The work is her story of searching. In it, she speaks to her lost husband, tells of the pain of absence, and reinforces the importance of not forgetting.

The theater is in the old neighborhood of La Candelaria, a few blocks from the Palace of Justice where her husband was last seen alive more than 36 years ago. Pilar helps the director and other actors set up the stage and lighting.

They are two hours away from performing as Pilar explains that many things have changed in the country despite the persistent violence.

“Thirty-six years ago, we did not talk about any of this,” she said. “My daughters spent their school and part of their university years not talking about their missing father because they had a stigma.”

The road has been long, but it has borne some fruit. For many Colombians, resistance has become life, and fear is no longer the main obstacle.

“Today, we victims come out with our heads held high. We scream, we get up, we demand—even if they kill us,” Pilar said. “Because resistance is hope.”

***

David González M. is an award-winning conflict and human rights reporter for international media. Twitter: @Davo_gonzalez