A demonstrator lifts the black Puerto Rican flag of resistance near Cueva del Indio in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, Sunday, October 9, 2022. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

ARECIBO, Puerto Rico — Faced with a slow response from the federal and local governments, activists took matters into their own hands on Sunday by tearing down illegal construction blocking the public entrance into the Cueva del Indio Taíno historical site.

Cueva del Indio —“Cave of the Indian”— is a Taíno cultural heritage site in the coastal town of Arecibo that is renowned across Puerto Rico and beyond due to the petroglyphs carved into the cave’s walls.

Since 2016, activists claim the two publicly accessible paths to the east and west of the cave have been blocked off. These claims are based on a 1974 land demarcation filed by the Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA, in Spanish) that was published by independent journalists José Luis Lebrón and Lorenzo Delgado Torres, which outlines a public path that should lead directly to Cueva del Indio.

After a musical demonstration on the beach, where people danced to the rhythmic drumming of bomba, activists wound their way through the beach and the road to rip away the wooden fence that blocked the cave’s entrance. While ultimately peaceful, there was a brief verbal confrontation with private security personnel and the “owners,” as they identified themselves.

Activists placed the torn wooden fence against the parking lot’s fence, creating an extra barrier of separation between them and security. Demonstrators made clear that they were not interested in ripping up the second fence, even though it was also blocking off private land, explaining that they only wished to open the public pathway to the cave.

Multiple community members and activists told Latino Rebels that they had been demanding the government to step in for months before deciding to step in themselves.

“I’m an elderly lady,” Julie Algarin said. “I cannot use the access they have through the beach.”

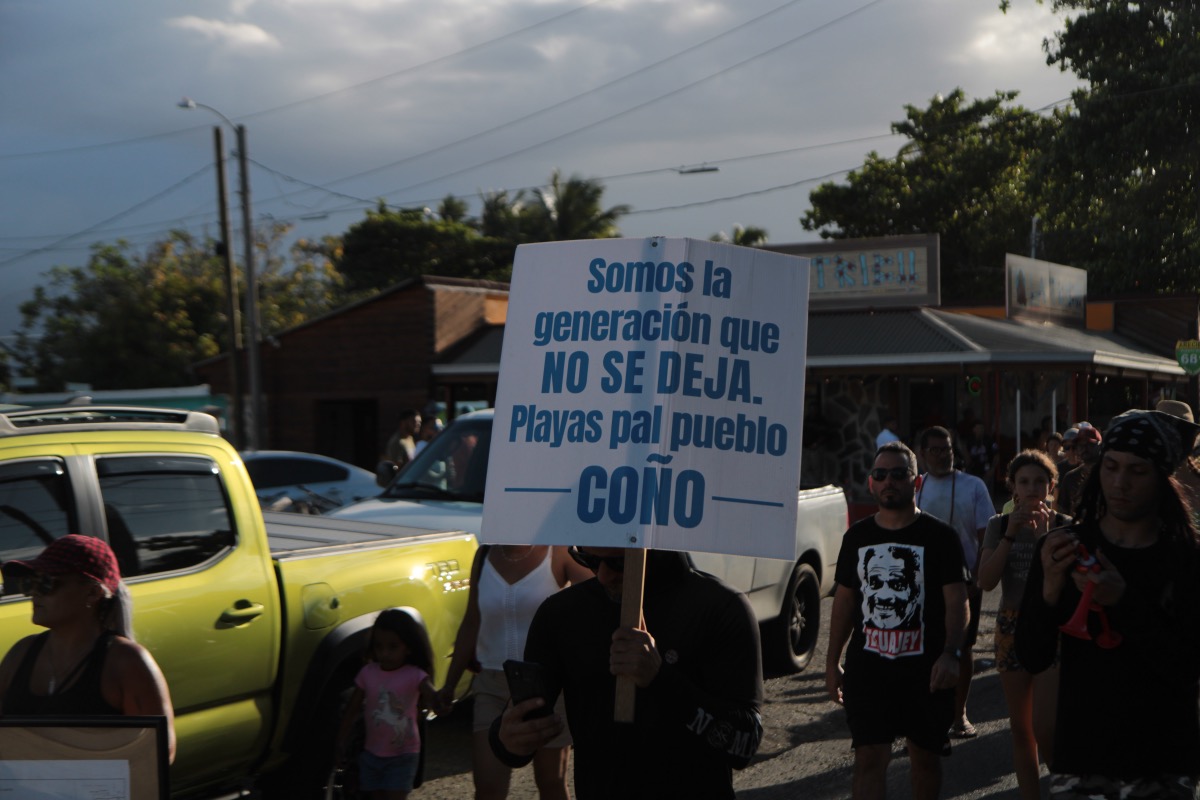

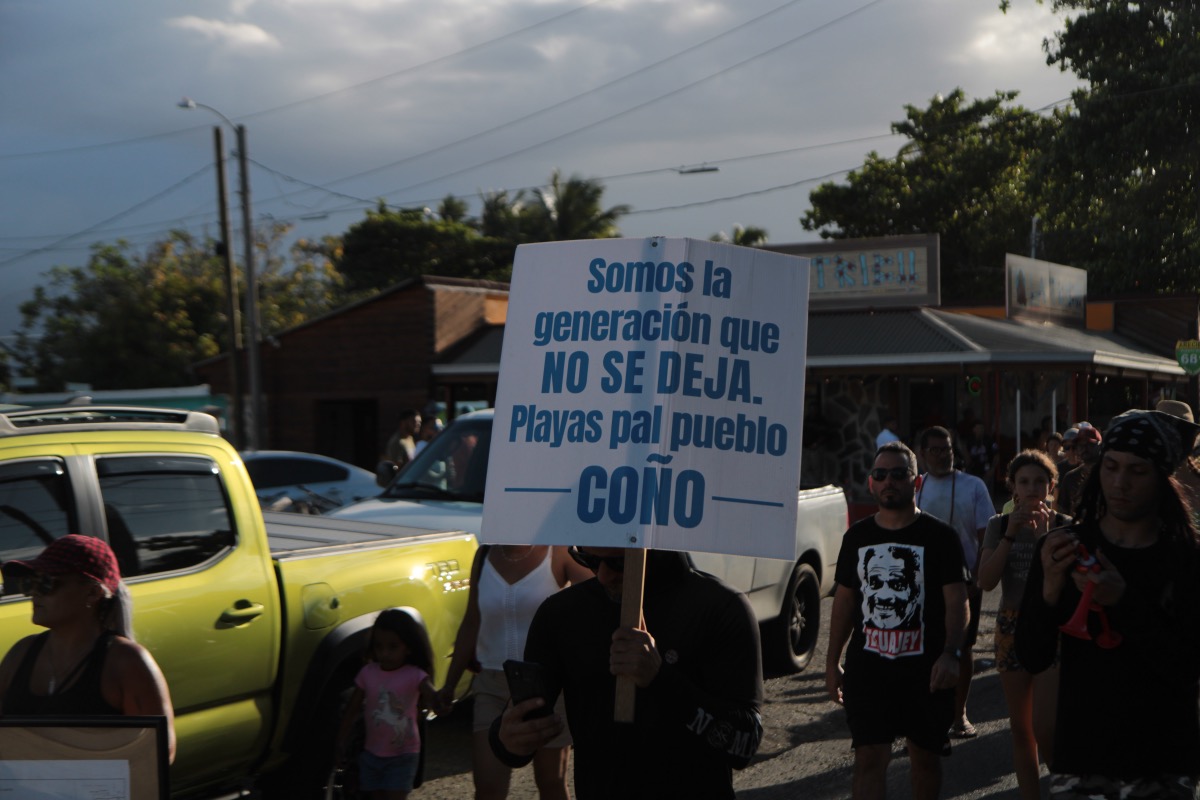

A demonstrator holds a sign that reads “We are the generation that will not put up with anything. Beaches for the people damnit” near Cueva del Indio, Arecibo, Puerto Rico, Sunday, October 9, 2022. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

Before activists removed the wooden fence, the only public access to the cave was by climbing jagged rocks on the beach to go around and then come into the cave from the bottom.

“You don’t have to legislate anything here,” Defendendiendo la Cueva del Indio (DCI-681) spokesperson Lauce Colón Peréz told Latino Rebels. “You don’t have to create anything here. What you have to do is implement and comply with the things that already exist.”

Multiple activists pointed to two laws that, in theory, should have restricted the construction of the wooden fences that encircled Cueva del Indio.

The first, the Docks and Harbors Act of 1968, commonly referred to as the terrestrial maritime zone law, dictates that there should not be any permanent structures built within 50 meters of high tide along the beach. Activists measured the distance from the terrestrial maritime zone into the zone of separation, which is where the 50 meters ends, using yellow rope that reached well into the area that had been fenced off.

“They are usurpers, not privatizers,” environmental activist and former gubernatorial candidate Eliezer Molina said.

Eliezer Molina, an environmental activist and former gubernatorial candidate, speakers to demonstrators near Cueva del Indio in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, Sunday, October 9, 2022. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

The second law dictates that any place containing archaeological remnants is deemed a “public utility and property of the people of Puerto Rico.” Activists pointed to section 13 of the law, which mandates that anybody found to have damaged or mutilated archaeological artifacts should face a fine of up to $5,000 or five years in prison.

Activists also pointed out that José González Freyre, owner of Pan American Grain, had violated the DRNA’s Regulation 4860 by appropriating public land for his own private use.

A small cadre of police was present but did not intervene with protesters, instead referring them toward the DRNA and the Institute for Puerto Rican Culture to resolve the problem.

Before Sunday’s demonstration, anonymous community members had come forward to denounce that they had seen pieces of Taíno pottery in and around the Smith Path, which was recently bought by Gonzalez Freyre. They also reported heavy machinery being used to excavate the area, citing concerns that it could damage the artifacts they had seen.

“The cave represents our culture and it represents us,” sociologist Alegna Malave Marrero told Latino Rebels. “We venerate the cave for ancient rituals.”

The wooden fence torn down and moved by protesters near Cueva del Indio in Arecibo, Puerto Rico, Sunday, October 9, 2022. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

Environmental activists protesting and removing illegal construction built within the terrestrial maritime zone is nothing new in Puerto Rico. There have been over half a dozen protests across the archipelago, with activists denouncing illegal construction on public beaches.

In Rincón, activists removed a cement structure that was infringing on the terrestrial maritime zone and endangering the nesting habitat of the hawksbill sea turtle.

People from all areas of Puerto Rico have formed a coalition dedicated to protecting the archipelago’s natural resources. Sunday’s event included activists from Campamento Carey, who protested for over a year in Rincón, alongside others who had attended the anti-beach privatization protests in Dorado and Ocean Park earlier this year.

Latino Rebels reached out to the DRNA for comment but did not receive a response at the time of publication.

***

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco is a freelance journalist, mostly focused on civil unrest, extremism, and political corruption. Twitter: @Vaquero2XL

[…] post Activists Tear Down Illegal Construction at Taíno Cultural Site appeared first on Latino […]

[…] Source link […]

[…] Credit: Source link […]