A man blows into a conch shell during a protest at a beach in Rincón, Puerto Rico, Tuesday, January 3, 2022. (Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels)

SAN JUAN — Fed up with the slow government response, Puerto Ricans in beach towns along the western coast have set up encampments to demand action be taken to stop illegal construction from further destroying the environment.

The coastal towns of Aguadilla and Rincón are well known for their beautiful beaches and greenery, both of which are treasured by the local communities. But these natural resources have been put increasingly at risk by rampant illegal construction.

There are reports that some of the construction was built illegally, and others have already been decreed for demolition but have not yet been removed. So activists, locals, and politicians have begun setting up encampments, after feeling like they have exhausted every other legal avenue.

“We do not have any other choice than being here with our presence and putting pressure so that environmental laws are complied with,” Rep. Mariana Nogales Molinelli of the Citizens’ Victory Movement told Latino Rebels.

Rep. Nogales Molinelli set up Campamento Pelicano on Monday, January 2, 2022 to demand the four construction projects built by developer Carlos Román Gonzálezon atop Cueva Las Golondrinas be torn down and for construction to cease immediately. She and the activists who accompany her at the camp are also demanding the company stop taking over public and private lands that belong to locals living near the construction site.

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels

Campamento Pelicano is named after the pelícano pardo (brown pelican), one of the species of waterfowl whose habitat is endangered by the illegal construction. The other species is the golondrina pueblera, or cave swallow, which Cueva Las Golondrinas is named after. Members of the encampment painted a mural of a pelican on top of the cave on the building next to their camps.

Aguadilla Pier Corporation, which is owned by Román González, runs a fuel port out of the historic Muelle de Azúcar in Aguadilla. In 2020, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sanctioned RL partners, which acquired the port in 2018. Earlier in the year, the U.S. Department of Natural and Environmental Resources (DRNA) erected two structures on top of the cave. The DRNA later ordered their demolition in 30 days, but so far the order has not been followed.

The EPA has also ordered The Cliff Corporation and Grupo Caribe, which is building the Cliff Villas Hotel and Country Club near the cave, to comply with the Clean Water Act and a construction permit for stormwater runoff. The agency still has an active case with The Cliff Corporation and Grupo Caribe, which Ramon Gonzalez is president of, according to EPA spokesperson Brenda Reyes.

“They are not developers, they are destructors,” Rep. Nogales Molinelli told Latino Rebels “I insist on not using the term ‘developer’ because all they do is destroy. Developing is protecting natural, cultural, and historical resources.”

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels

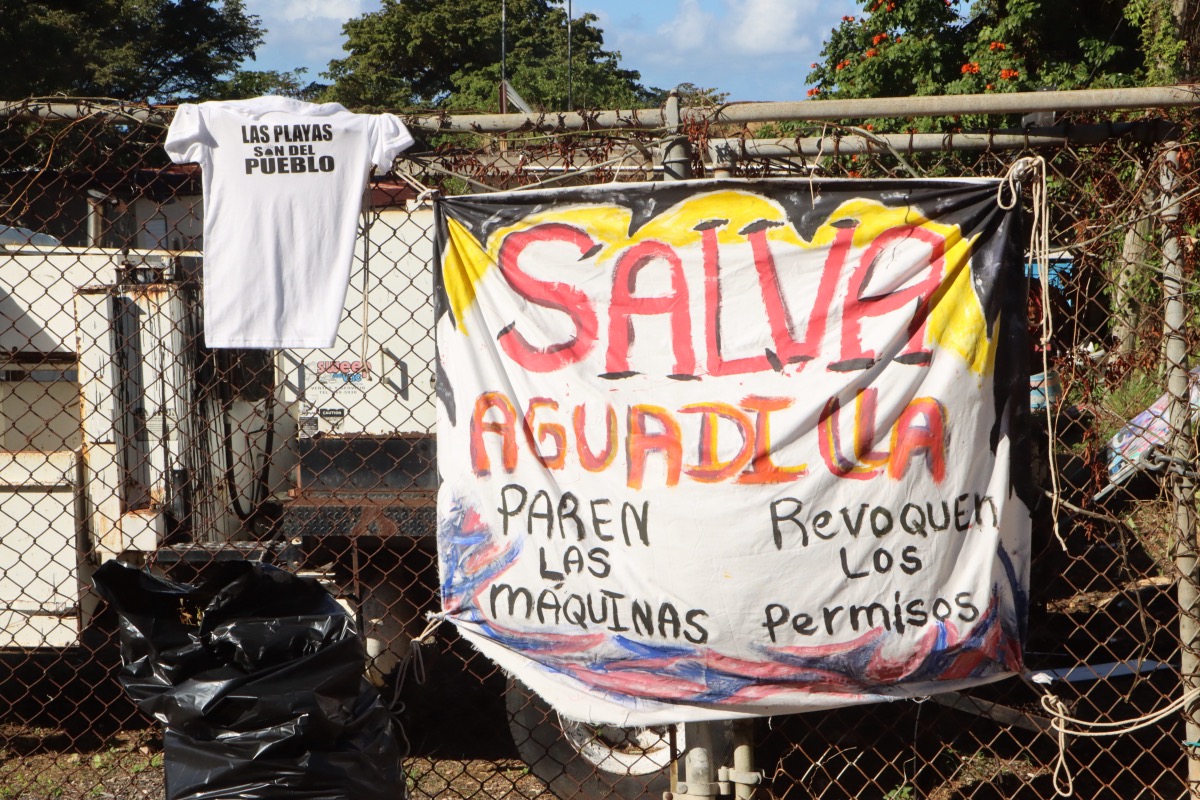

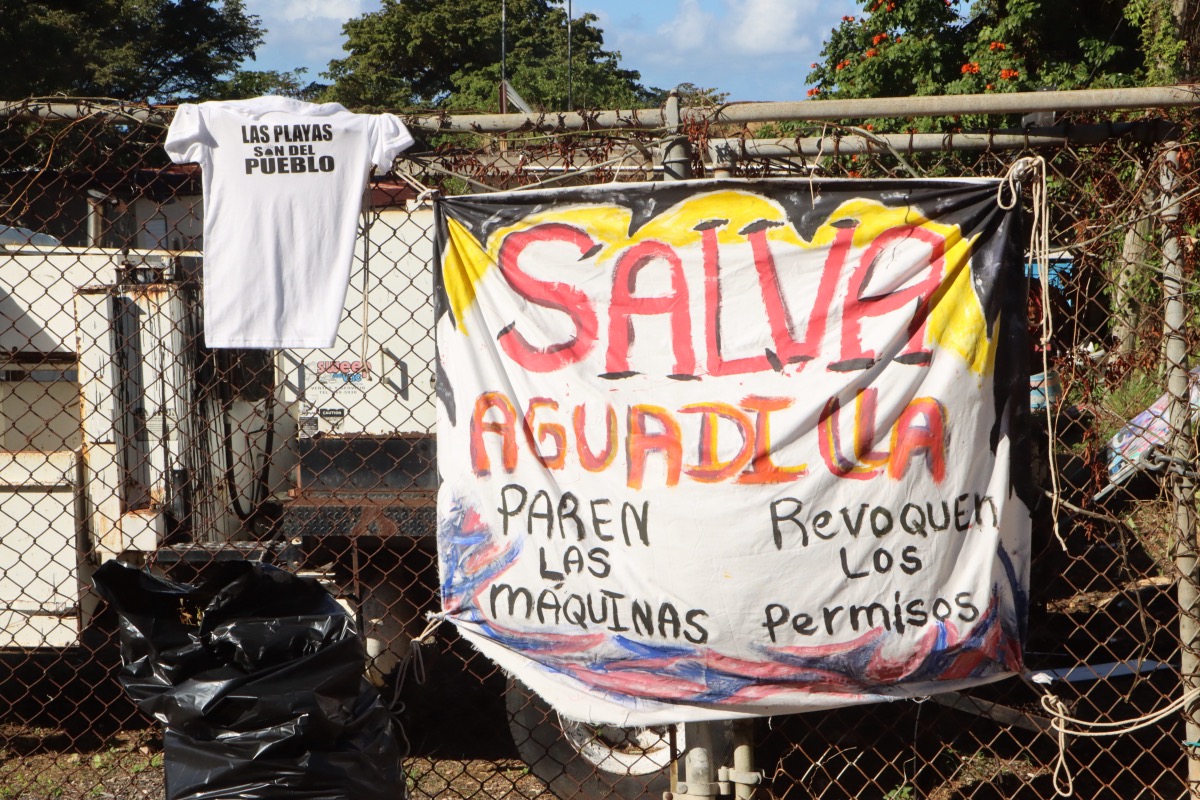

Locals allege that the developer has illegally destroyed parts of the cave and the greenery so that when the government conducts an environmental impact study, they will find that the construction would not lead to any major damage to the area’s natural resources. The conservation group Salva Aguadilla alleges that there has been new construction without the required permits.

Members of the camp have said that they’re willing to stay on the outskirts of the construction zone “for as long as it takes.” A few days after the camp was set up, the metal gate was torn down during the night, likely by members of Campamento Pelicano.

Latino Rebels observed multiple men wearing balaclavas drive into the construction zone. Locals allege these could be police working security for the companies building in the area, but these reports could not be independently verified.

As recently reported by Marea Ecologista, the construction has devastated the greenery in and around Las Golondrinas cave.

EXCLUSIVA: A la luz expediente Cueva Las Golondrinas mientras comunidad exige terminar con impunidad. Accede al expediente completo de @DRNAGPR versus Aguadilla Pier y a denuncias recientes documentadas con fotos y videos. https://t.co/u6fGBrNgwV 📹 obtenido por Salva Aguadilla. pic.twitter.com/bQwyWuYjtc

— Marea Ecologista (@MareaEcologista) January 4, 2023

Pictures shared with Latino Rebels by a local at the camp show how the area looked before the construction began, with large swaths of greens and tall trees that have since disappeared.

Rep. Nogales Molinelli presented RC 830 to the Puerto Rico House of Representatives, which aims to investigate illegal construction that damages the environment. The project was voted for unanimously. But Rep. Nogales Molinelli was told by the Natural Resources Commission that they will not attend to it because it was “not a priority,” she told Latino Rebels.

For his part, Gov. Pedro Pierluisi has agreed with the DRNA’s order to demolish the structures built on top of Las Golondrinas cave and said that he will follow up with the organization’s secretary, Anaís Rodríguez.

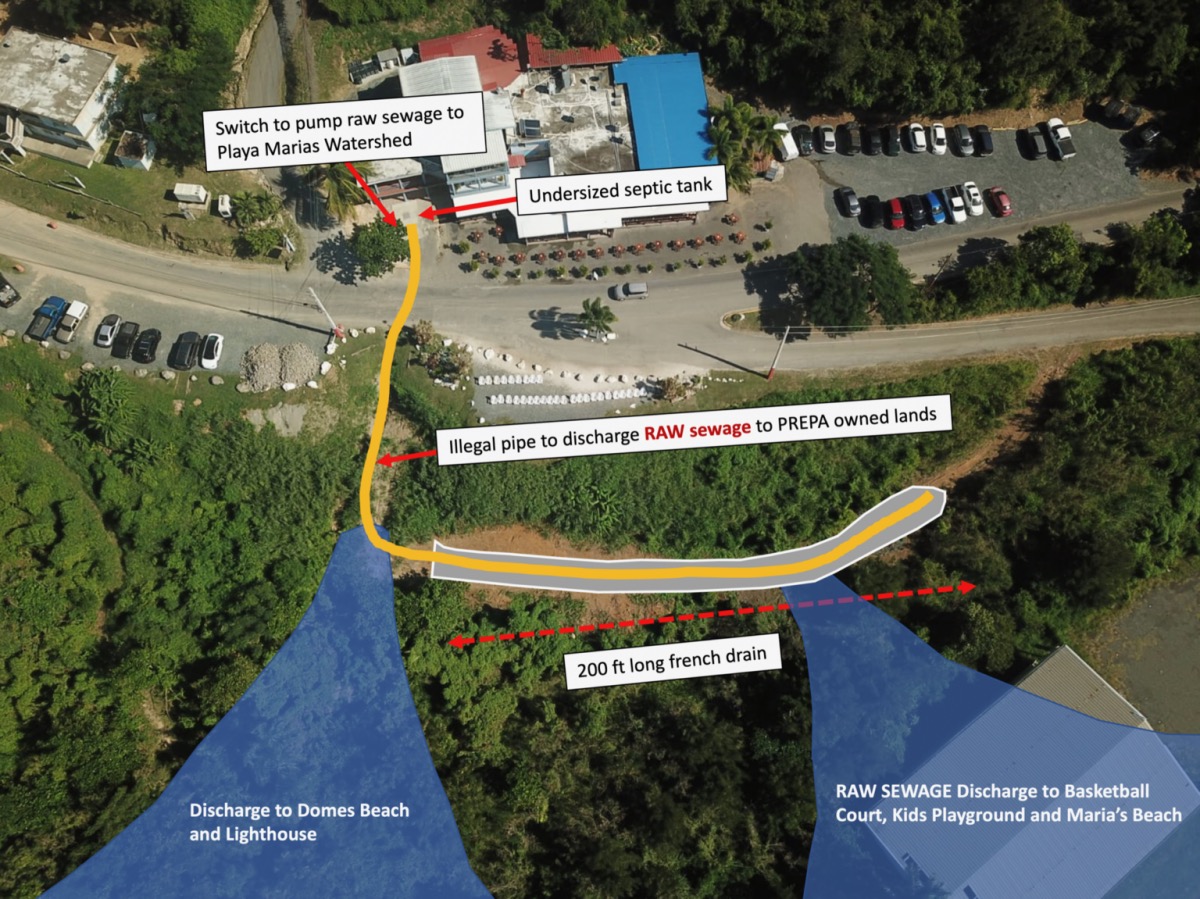

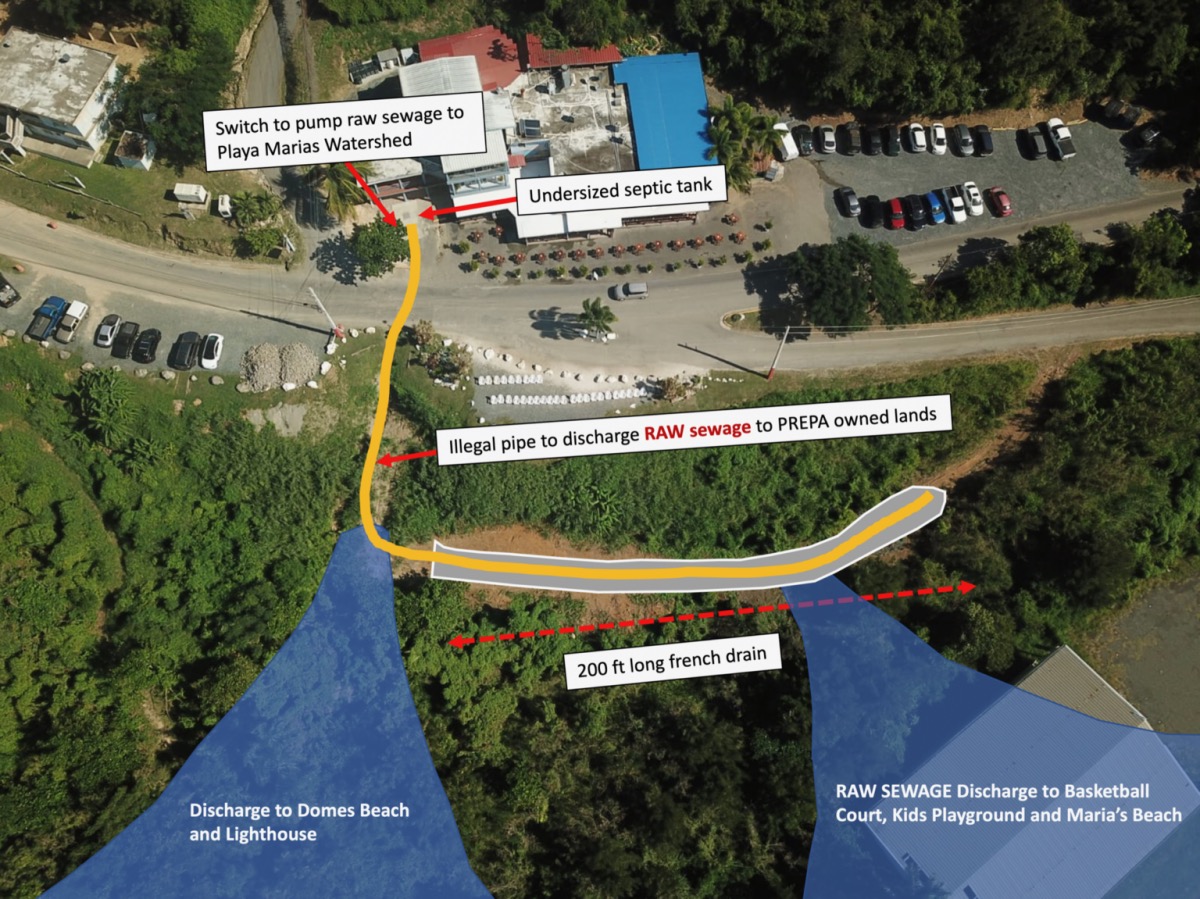

An hour away, in Rincón, community organizations and locals gathered at a closed basketball court to discuss an illegal discharge pipe coming from the Beach House, a hotel and restaurant, dumping raw sewage into public land that then ends up in several beaches, a children’s playground, and the basketball court where they were holding the conference.

“This (pipe) was built to be permanent. We found it three months after it was built, but this could have contaminated and even killed people, which is why this is so indignant,” Dr. Miguel Canals Silander, a community member and director of the University of Puerto Rico’s Center for Applied Ocean Science and Engineering, told Latino Rebels.

The environmental group Surfriders Foundation sampled some of the water in the areas where the sewage has leaked and found large amounts of E. coli bacteria. The organization alleges that the sewage going to the water is “an outbreak waiting to happen.”

Community members discovered the pipe a few days before and immediately cut the pipe so it would stop flooding the area where they surfed.

Sewage discharge map provided by Amigos y Amigas de Tres Palmas

“This (pipe) is the source of the problems in the water,” said Ramon Díaz Zambrana, an environmental planner and spokesperson for the community group Amigos y Amigas de Tres Palmas. “Evidently, the people who got sick are from this situation. Obviously we have to prove that with a lab, but you don’t have to be too smart to see it.”

Amigos y Amigas de Tres Palmas says it has observed the pestilent water at Domes and María beach since September. Latino Rebels talked with several surfers who explained that they could smell the sewage runoff when they went out to catch waves. Some mentioned suffering multiple types of infection, but they could not definitively tie it to the sewage.

Latino Rebels observed a mass of flies and a foul odor at the runoff site near the basketball court and at the end of the presumed illegal drainage pipe.

Latino Rebels attempted to get in contact with Kevin Killarney, owner of the Beach House, on the same day that the press conference was held, but the restaurant was quickly closed off by security and police as people attending the press conference started gathering outside the building. Protesters then began to move and occasionally throw chairs and lamps into the building’s private space from the public area they were occupying.

Later that night, activists set up a tent on the public land the Beach House occupied with lawn furniture.

In both Aguadilla and Rincón, locals and activists are somewhat unwilling to believe that other types of action will lead to the construction being halted, which is why they decided on building the encampments. Activists at both sites mentioned that the DRNA’s lack of resources has systematically led to the environmental issues that they’re protesting.

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco/Latino Rebels

“In my case, I’m gonna be here at the time I need to be here. But I also see it as an invitation for people here to continue the camp for the time needed to put necessary pressure,” Rep. Nogales Molinelli told Latino Rebels.

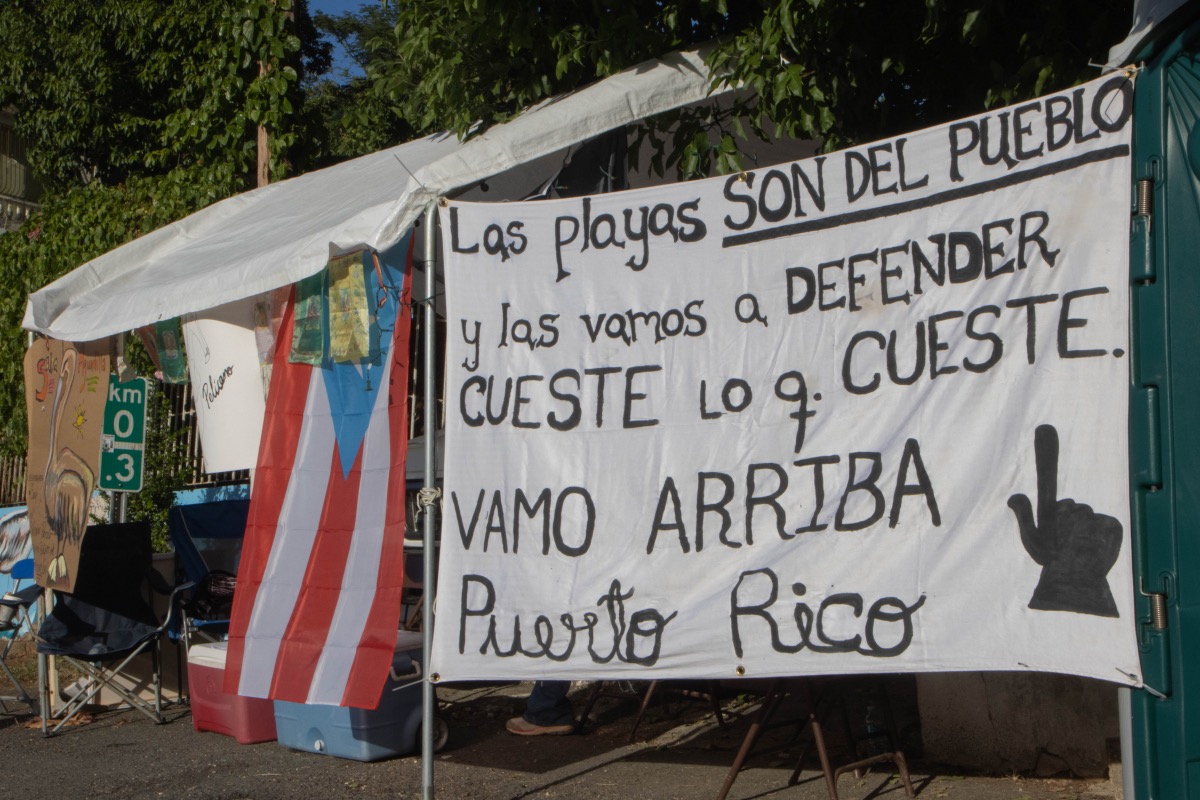

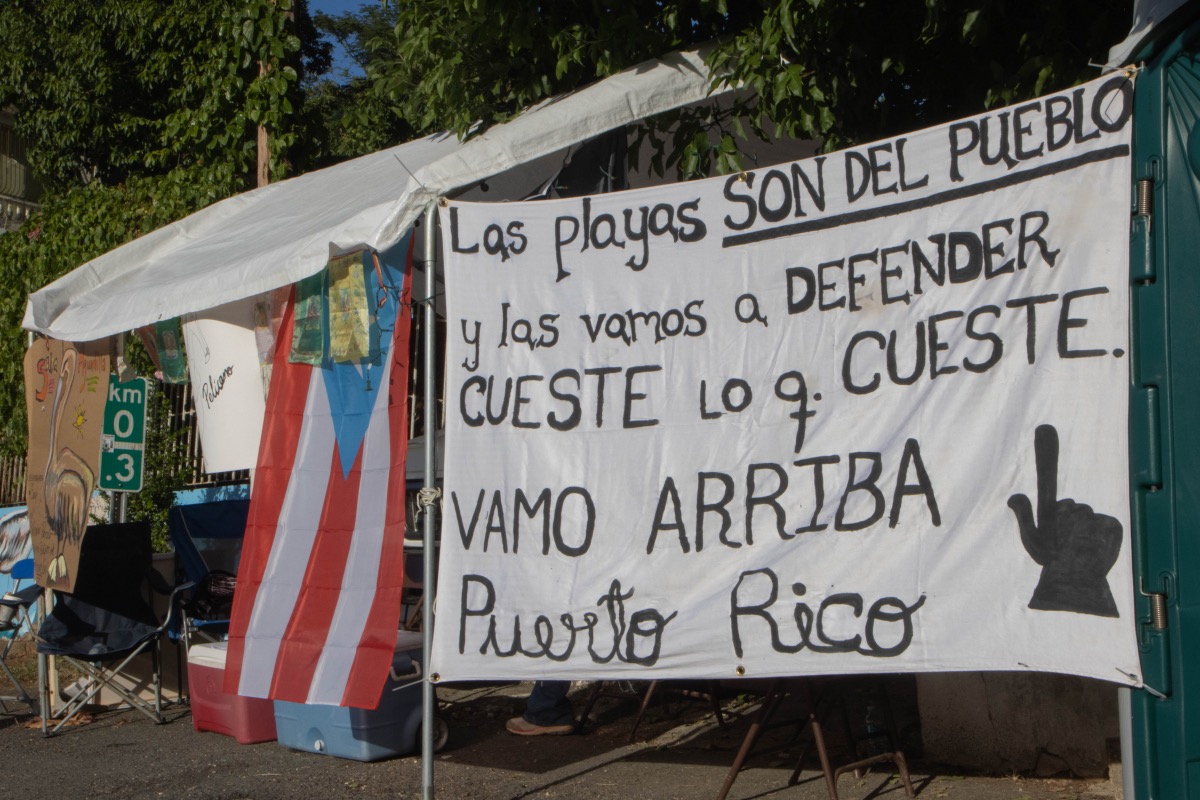

The fight to keep Puerto Rico’s beaches public has been reinvigorated over the last two years as more and more everyday Puerto Ricans exercise their rights. Beach encampments have become increasingly common along the western coast.

Rincón is the home to the first beach encampment, Campamento Carey, at the edges of the Sol y Playa Condominium that had built a pool too close to the beach. What made the situation more grievous was the fact that the beach is the nesting ground of the hawksbill sea turtle, which the illegal construction was destroying.

The camp has been there since the summer of 2021, and the activists eventually won their battle for the beach, tearing down the half-built construction by themselves.

***

Carlos Edill Berríos Polanco is the Caribbean correspondent for Latino Rebels, based in San Juan, Puerto Rico. Twitter: @Vaquero2XL

[…] of Tortuguita in Atlanta, private security forces shot at Puerto Rican environmental activists who turned to direct action to secure their collective right to the land. One activist was struck with a bullet while defending […]

How can we help?