Mexico vs United States CONCACAF Cup, October 10, 2015, Rose Bowl, Pasadena, CA (Photo Credit: Joel Tena)

Watch any soccer game of the Mexican national team or from Mexico’s LigaMX and inevitably you will hear that word. As the goalie readies for a goal kick a cheer rises from the crowd: “Ehhhhhhhhh…..” until like a slingshot the pent-up verbiage is released the moment laces strike the ball: “¡PUTO!”

Most fútbol fans are aware of this behavior. Many Mexicans who witness it will chuckle or laugh, or roll their eyes at the low-brow humor. But there are others who see it as another example of their stigmatization, ostracization and isolation —from their families, from their communities— because they are gay. Because for many in the LGBTQ community, the word “puto” is a homophobic slur.

Ask your average Mexican soccer fan (ask your average Mexican) if “puto” is anti-gay and chances are you will hear a resounding “No.” Many folks of Mexican descent, myself included, grew up with the word meaning something to the effect of “male prostitute,” “gigolo,” or “man whore”—the counterpoint to “puta,” which means a female prostitute. It was a rude term. You wouldn’t use the word in front of older adults you respected and certainly not something you would say in front of your parents.

Homophobia is prevalent in Mexican culture (as it is in the U.S. and in much of the world), and sadly there were and are many other words that one would use to express those feelings.

But it does emasculate. It does demonize and disassemble traditional male heterosexual roles. Since there is no reason a male prostitute couldn’t sell his “services” to either a man or a woman, there is the implication that it might be related to sexuality. It’s certainly common for words questioning one’s sexuality to be used has verbal weapons to dehumanize and negate another individual, and to contrast them with the assumed positive, preferred lifestyle of a straight man.

These sentiments didn’t just spring forth in a vacuum. Mexican culture, like all other post-colonial cultures in our Américas, has traditionally frowned upon, dismissed, ridiculed and attacked its queer sisters and brothers. In our patriarchal societies, men are seen as superior and dominating, and woman are seen as submissive and inferior. To be gay meant to be no longer on the level of other straight men, but to be on level with women. Someone to be dominated, ridiculed and, deep down, threatened by.

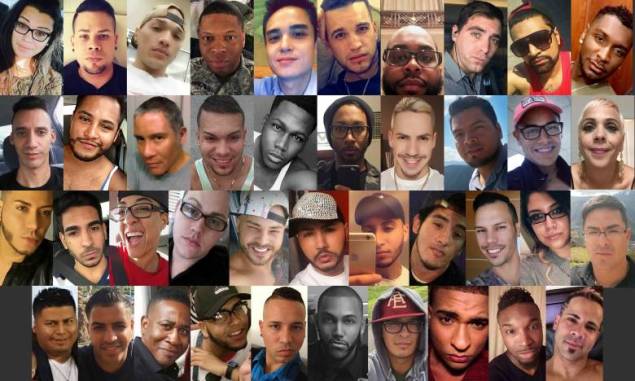

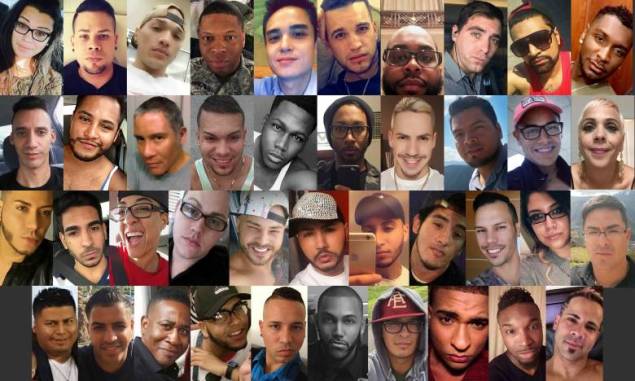

It’s these hyper-masculine cultures in both the United States and Mexico that conditioned men to question other men’s sexuality and forces younger men to stand vigilant against any such attacks lest they be perceived as less than a man. It’s this social conditioning which leads to the number of acts of violence against women, shootings, murders and homophobic attacks. It’s no coincidence that most murders are committed by men, like the horrific mass killing of 49 people, predominant queer Latinos who were mostly of Puerto Rican descent, by a deeply violent, homophobic, and bigoted individual in Orlando last Sunday.

What connects Mexico to this tragedy in Orlando is the extent to which homophobia manifests itself through violence there. Mexico is considered by researchers at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) to be the second most dangerous country in the world for LGBTQ folks. In its recent study, the Programa Universitario de Estudios de Género found that between 1996-2015 over 1,200 homophobic murders took place in Mexico, about one a week. And this isn’t limited to interpersonal violence. Mass shootings have also taken place. Last December, three people were murdered when gunmen fired upon the crowd at the Reina Gay Festival outside of Acapulco. Just this past May, five people were killed and over a dozen injured when four gunmen opened fire inside a packed gay nightclub in the university town and Veracruz state capital of Xalapa.

Since Orlando, we have heard a refrain amongst the LGBTQ community: the attack on Pulse hits deep because LGBTQ nightclubs are more than just clubs. Gay and lesbian bars and clubs are spaces of freedom in a heterosexual world, spaces that allowed queer folks the ability to be who they really are to talk, dance, love and be together—free from the repercussions of a homophobic and bigoted world on the outside.

That impact was felt that much more among the Latino queer community. As a straight Latino man, the LGBTQ folks I know say they feel alienated from many mainstream (white) gay community spaces, and have a hard time finding space among other people of color. Having a Latin-themed gay club meant that those most isolated, disenfranchised, and excluded from their own communities (both their Latino families and friends as well as other queer folks) had a place to call their own, a safe place… shattered and devastated by the massacre in Orlando.

There are so many aspects of being gay and lesbian that most straight folks like myself can’t even begin to understand. For instance, given the homophobia present in Latino societies, many brown folks choose to remain in the closet where it is “safer,” both physically and emotionally, and allow them to continue with familial ties. Sadly, because of Orlando, there are families who will only find out through the death of a loved one that they were gay. And while times have changed, and families and communities are much more embracing and loving of their LGBTQ sons and daughters, sisters and brothers, many folks still remain rooted in the homophobia and bigotry prevalent in our societies, denying their love and casting shame upon their own flesh and blood.

Therefore, many queer Latinos stay hidden because to do otherwise would expose them to the harm and pain of being denied one’s family, friends and social network.

Then they go to or watch a Mexican soccer game, where they hear an anti-gay slur chanted by thousands.

Claims that no one is offended because no one says anything ring hollow given the reality and the necessity of many queer folks to remain in the proverbial shadows.

Claims that they are just words also fall flat.

We know words can be isolating, damaging and can hurt. We in the Mexican/Chicano community only have to turn on the TV to hear and experience how much pain words can inflict, and how dehumanizing they can be. Whether it’s Trump labeling immigrants “rapists” and “drug dealers” or sports reporters telling us they didn’t think Mexicans were “that smart,” we as a community know all too well how this kind of negative language can affect folks for the worse.

The pain and hurt caused by people who claim no ill will towards us as a group. How are we to know what that feels like? We don’t have to imagine. We as a Mexican/Latino/immigrant community know all too well.

Why then is it so hard for Mexicans, specifically Mexican soccer fans, to stop using the word “puto” at games?

For starters, folks have been saying it for a while. It’s not some long-standing tradition that some make it out to be, but it has been fairly omnipresent at games involving Mexicans, and now throughout Latin America, over the last ten years.

Yet that is still no excuse.

It’s same weak sauce rationale white Southern racists use for flying the Confederate flag these days: that it’s part of their heritage and culture, and that it doesn’t mean what you think it means.

Even if the “puto” chant were use for a century, that doesn’t excuse it for the pain it causes others. And as stated above, many folks who say it don’t think that it’s homophobic. They do not realize the broader implications of using the word. It is true that sometimes we don’t know pain we cause others. But when made aware of it to continue to inflict that pain is unconscionable.

And fans have indeed been made aware.

During the 2014 Brazil World Cup, more and more footy supporters and LGBTQ activists and allies have been speaking out against usage of the word. At that tournament, Mexico fans used the word during match play. Soon, more and more people from other countries heard it. Many fans, especially those here in the U.S., saw the word as undeniably homophobic.

FIFA, world football’s governing body, heard the concerns and earlier this year began leveling fines to football associations where the chant has been used. This happened in several Latin Americans countries, including Mexico. The fines were relatively small, but came with the ominous warning that FIFA will continue to review the matter, with more penalties to come, including stiffer fines and possibly having to play official games behind closed doors, should the chants continue.

In the last month, the Mexican Football Federation (FMF) put out a series of public service announcements featuring star Mexican goalies Guillermo Ochoa, Alfredo Talavera and Jesus Corona with the tagline “Ya párale”, or “Stop it”, in reference to the chant, to help educate fans.

Unfortunately, these efforts have been underwhelming and are clearly not working.

Mexico is currently in the midst of the 2016 Copa América Centenario, a celebration of South America’s older soccer tournament. The games are being held in the United States for the first time, and Mexico, with its incredibly large fan base here (it’s not hyperbole to say that the Mexican national team is the single most popular soccer team in the United States) was invited and is seen as one of the favorites to win the tournament. In every El Tri match, no matter what city it is being played in, the overwhelming majority of the fans are Mexican.

And at every goal kick, the unmistakable cry of “puto” is heard throughout.

The last such occurrence is seen by some as the biggest black eye of Mexico’s tournament run thus far. On Monday, less than 48 hours after the homophobic Orlando attack that saw many Latinos die (including three Mexicans), and after a touching moment of silence where both El Tri and the Venezuelan national team stood in honor of those who lost their lives, as soon as Vinotinto goalie Dani Hernández touched the ball, the anti-gay “puto” chant rang out.

What will it take to change our behavior?

First, the Mexican soccer community has to formally acknowledge that this is a problem. Homophobia has absolutely no place in our society, and that includes our soccer culture. We must absolutely open up and embrace folks regardless of sexual preference. Because it’s not an “us” vs “them,” it is ALL OF US, our sisters and brothers, who have the absolute right to be, free from stigma, shame and violence.

Second, the whole framing of this issue is wrong. We shouldn’t stop using the word because of what FIFA may do. We all know the problems and inherent contradictions within FIFA. The fact they are going after fans using a homophobic chant while working with governments like Russia, known to be openly hostile to their queer community, and Qatar, which outright criminalizes homosexuality, exposes their ridiculous hypocrisy in the name of profit. FIFA, Russia and Qatar should hang their heads in shame.

Meanwhile, we should do the right thing, always. We should think about the way the “puto” chant makes those around us feel. We should acknowledge that it is wrong to knowingly ostracize, alienate and dehumanize a large segment of our population. This isn’t about being tolerant. It is about realizing who we are as a people and who we are as a society as a whole. We are queer folks and straight folks, and we should be open, accepting, and embracing… because that’s what makes us a family.

Third, the Mexican Football Federation needs to take this issue seriously. Their initial attempts seem bungled at best. Not calling out what they want stopped, and why it should be stopped, is a problem. Not working with LGBTQ groups in Mexico and the U.S. was a huge mistake. The Federation should tackle the problem head on, from talking more direct about the chant with its ad campaign, to educating its players on why this need exists, to working with the fans and supporters groups to help them in their own efforts to eradicate the chant from the stands.

Finally, fans need to step up. We need to make homophobia as toxic and repulsive as racism in the stands. We wouldn’t stand for monkey chants. We would call those people out for what they were doing. We should do the same for the folks who knowingly foster and perpetuate a climate of hate.

Many on both sides will be angered by these suggestions, both those who will swear they are not being homophobic when they yell “puto,” and those who condemn Mexican fans for not terminating the word from their lexicon with extreme prejudice.

Sorry.

To my Mexican homies, you are on the wrong side of history and morality because it is more important to listen and learn how your actions impact others than which definition of a word you can cherry pick from the internet. Plain and simple, you are not right and need to move on, embracing your LGBTQ sisters and brothers in the process.

To folks in the U.S., primarily white folks, who don’t understand why the chant won’t stop immediately, there needs to be some kind of understanding and reflection of the mountain of prejudice and misunderstanding in relation to LGBTQ issues that exists both in our Mexican culture, and in U.S. society. This isn’t about bad people doing bad things. It’s about people not knowing, or not believing that what they are doing is bad. It’s about educating and opening those up people to understand what they do to their own folks. It’s about learning and supporting efforts among the Mexican and Latino communities already working to help eradicate homophobia.

Don’t get clouded by your own sense of moral superiority, cultural insensitivity and even latent racism, especially right now when a major presidential candidate is basing most of his campaign on scapegoating the Mexican community. Frankly, if we could solve the Mexican fans’ homophobic chant overnight, we should bottle and sell that plan to a world suffering from longstanding bigotry. Especially here in the U.S., homophobia and racism haven’t been solved and we continue to deal with their ugly manifestations every day. To expect differently from Mexicans is hypocrisy of the highest order.

This doesn’t mean we accept the status quo, nor does it mean we don’t try our hardest. It means we do so knowing full well that fans (people) don’t change immediately, but if shown the way, they will change for the better. As Sergio Tristan, founder of the Pancho Villa’s Army Mexican national team supporters group has said many times, “It’s going to take time, it’s going to take one fan at a time, but (the “puto” chant) will be eliminated.”

Let’s start working towards that goal: together and today.

Let’s work to end the hate, end the “puto” chant, and let love win.

We’ve lost far too many of our loved ones to do anything less.

***

Joel Tena is a proud father, husband, son, Mexican. When he’s not lovingly arguing with his son as to who should be Barcelona’s starting goalkeeper, he’s in the streets of Oakland fighting for social, racial, and economic justice. He tweets from @joeltena.

Like everything else, it’s more important to look at the context of the word. Sure, if you look at the word “puto” by itself a lot of people will think it’s a homophobic slur, but that’s not how it’s being used. Imagine this: you’re at a soccer game, sitting at the stands at your team’s stadium and cheering your team on. There’s home field advantage all around you, in the stands and the pitch your team’s players know so well, and it shows because your team is getting close to scoring, but the goalkeeper is having the last say and keeping the shots out of the net. As a fan, how does that make you feel? What does it make you think about the goalkeeper, who is only visiting your home stadium and more than likely won’t be back for a year or maybe two to play against your team again? That he’s gay? NO! It makes you think he’s a PRICK! That’s what that chant means!! It’s not meant to be homophobic at all, and that’s why it hasn’t stopped and is louder than it’s ever been! If you notice, that chant is reserved for the goalkeeper of the visiting team, not just any goalkeeper. Don’t get me wrong, I realize that the LGBTQ community has been discriminated against for a long time and that enough’s enough and they wanna make their voices heard, but there’s just no place for that in this one because there’s no discrimination in the chant, and I really think everyone should understand that first. Even people who speak Spanish around the world know this. I agree with the author that it’s not a nice word and you wouldn’t use it in front of your parents, but they all know what “puto” is used for. Yes, some people use it as a slur, but it is also used to insult someone you don’t know or don’t know very well who has done you wrong. Don’t take my word for it, ask around. If you speak spanish, then you know what I’m talking about.

I would say the problem is that in the past ten plus years foul language has become the norm. You will hear it on the radio and TV and it is now common to hear 3 and 4 year old children swearing without consequences. So the old chants like at baseball games “Swing” have no effect and now people will say anything to distract a player. It in my eyes is not that it is homophobic which would mean I am afraid or against homosexuals, but a slur that is very distracting. A male prostitute does not necessarily mean they are homosexual as there are heterosexual male prostitutes. However in today’s society for trying for total inclusiveness any word that has a hint of being derogatory is now seen as phobic in one way or another.The issue that I see is that it is okay for the minority to use these phobic slurs but not the majority. Until the minority stops using the same slurs for the same purpose it will continue to happen.

Another “Latin-X” with Anglo-phone values trying to police the Spanish language. ‘Puto’ is not the equivilant of ‘Maricon’, Nice try but not gonna work.

Exactly. Libtinas need to chillax.